The Chiffon Trenches

Prêt-à-porter, aka ready-to-wear, was taking off, and Karl always had a knack for delivering bizarrely innovative clothes that were unanimously acclaimed by retailers and press alike. He’d make a print with robots and space mobiles and turn it into a $1,000 dress. His jewelry could be big plastic red roosters or chickens, or plastic Magic Marker–colored tulips on a necklace, over a luxurious foundation, like a black redingote wool coat, exquisite and expensive, made to last through generations.

The clothes were surreal and sophisticated, but most important, they were youthful and inspired. This was represented in Karl’s approach to the Chloé fashion shows. They purposefully didn’t have an assigned lineup of models and outfits. Backstage, Karl would tell the models to pick whatever they wanted to wear from the rack. That is unheard of even to this day, where shows are micromanaged down to the smallest details. After the show, he’d tell the models to keep the clothes they’d worn. They didn’t make that much money at that time and this was a way of saying thank you.

Interview was planning a Paris-themed issue, and Karl was due in New York to promote his new Chloé fragrance. Karl had never been profiled for Interview before, and Andy suggested that I conduct the interview, for which I am forever grateful.

I did everything I could to prepare for meeting Karl. Serious research. I knew Karl was influenced by eighteenth-century French style and that he was emulating it in his own personal life. As a longtime Francophile I knew the basics, but I dug deeper to prepare. I read every interview he had done and researched as many of the references he’d made as possible.

When we arrived at the Plaza, we were directed upstairs to a large suite. I sat down across from Karl in the living room, my notebook ready. Members of Lagerfeld’s entourage floated in and out of the bedrooms. Seated next to him was his boyfriend, the handsome and debonair Jacques de Bascher. Andy and Fred Hughes had accompanied me, as well as famed fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos, friends of Lagerfeld’s who had just returned from Paris to take up residence in New York. Antonio was creating visuals for the Paris Interview issue. In previous years, Antonio’s creative energy had helped drive Karl Lagerfeld. Now there was a noticeable chill between them. I wondered what the story was but focused instead on what I had come to do.

Lagerfeld was bearded and dressed in a bespoke crêpe de chine shirt and a six-foot-long muffler. I had on khaki Bermuda shorts, a pin-striped shirt and aviator glasses from Halston, knee socks, and moccasin penny loafers. We spoke about the eighteenth century: the style, the culture, the carpets, the people, the women, the dresses, the way the French entertained, set a table. It wasn’t labored or anything especially deep, but I learned a lot in that conversation and was grateful for the knowledge.

“Fashion’s fun and you can’t really take it too seriously. Frivolity must be an integral form,” Karl said to me. As we spoke, Antonio drew us, while Juan directed him on the right position and attitudes to convey. Andy and Fred sat quietly, the minutiae of proper attire in an eighteenth-century court likely going right over their heads. How exhilarating, being able to prove myself to Andy and his team as they sat quietly and listened. Karl seemed impressed by my desire to learn and gave me a great interview. My Southern manners helped, I’m sure. It would be easy to imagine how cocky and brash a young editor at Interview had the potential to be.

Afterward, we all had high tea. The whole thing was so elegant. Then, quietly, Karl asked me to follow him into his private bedroom.

Andy smiled widely and shyly, as though he couldn’t imagine what this was. I smiled too, nervously. I could imagine, but I was trying my hardest not to.

I followed Karl into the huge bedroom, crowded with Goyard jacquard trunks and suitcases of every possible size and dimension. He opened the trunks and, out like a geyser spitting forth toxic ash, he threw beautiful silk crêpe de chine shirts in kelly green and pink peony, each with a matching scarf.

“Take this. It will look good on you. Take that. I am tired of these shirts! You should have them.” He’d had these shirts specially made by the gross at the Paris firm of London haberdashery Hilditch & Key. They had long sleeves and beautiful buttons, like smocks. I took them happily.

Those shirts were the stars of my wardrobe; I wore them like a badge of honor, until they wore out. That’s how Karl and I first met. We would stay friends for forty years. Until we weren’t.

III

Andy poached Rosemary “Armenia” Kent from Women’s Wear Daily (WWD) and made her editor in chief of Interview. Rosemary lasted about a year, but Mr. John Fairchild, whose Fairchild Publications owned WWD, held a grudge for much longer. A mandate had been handed down—no pictures of Andy or Fred would run in WWD. Everybody from Interview was exiled.

John Fairchild, the king of fashion journalism, the master of WWD, and the inventor of W, could be cruel. Downright bloodthirsty. His rancor was all-consuming. For example, Valentino, early in his career, gave Rosemary Kent exclusive access to cover his vacation. Subsequently, Valentino decided not to invite her back. For that, Valentino and his partner, Giancarlo Giammetti, were airbrushed out of photographs at parties. If Mr. Fairchild couldn’t get Valentino’s face out, he would resort to assigning the generic label of “an Italian designer” to the caption.

Carrie Donovan, who was now the fashion editor of The New York Times, called me and said I should get over to Women’s Wear Daily. There was an opening. I was interviewed by WWD’s Michael Coady on a Friday and was offered a job as fashion accessories editor, covering scarves, belts, earrings, jewelry, and ancillary social nightcrawling of New York fashion society.

With Oscar de la Renta, in his showroom. Back then, I didn’t have a lot of money for fashion. I wore Bermuda shorts and knee socks to make my style statement. That hat is by Karl Lagerfeld and the shirt also. We are drinking white wine, which was served after fashion presentations in the Golden Age of Fashion.

© Thomas Iannaccone

The following week I started at a super salary: $22,000 a year. A massive leap from my $75 a week at Interview. I called my grandmother, my mother, and my father to share the good news. They were extremely happy, even if they didn’t quite understand what my job was.

Mr. Fairchild poached me, his revenge for losing Rosemary Kent; that’s how the fashion world runs. I’d worked at Interview for eight months and experienced some incredible moments in that brief tenure. I was grateful for everything Andy had done for me, but I knew this was an opportunity I couldn’t turn down if I wanted to pursue a career in fashion journalism. While I knew it might anger Mr. Fairchild, I planned on staying friends with Andy, knowing we would have to keep it on the down low if I wanted to keep my new job.

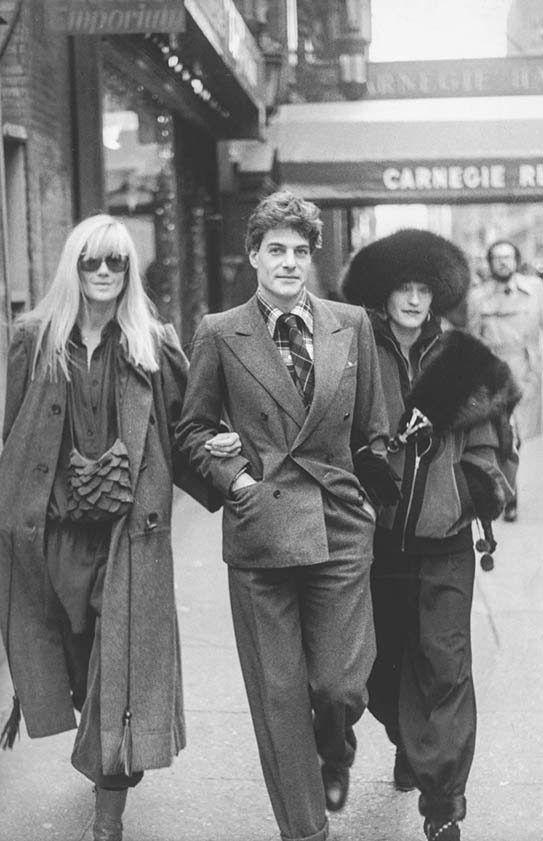

Photograph by André Leon Talley for WWD page one. Betty Catroux, Thadée Klossowski, and Loulou de la Falaise in New York.

Photo by André Leon Talley

My first day at WWD, I arrived confidently wearing my hand-me-down silk tunics and mufflers from Karl, with a Fruit of the Loom T-shirt and gray custom-tailored glen plaid trousers, with zoot suit–sized cuffs and wide hems. Mr. Fairchild didn’t say hello or acknowledge my existence. I would have to earn his greeting.

WWD was considered the fashion bible by most, which therefore made Mr. Fairchild a kind of god. He could destroy a designer by refusing to cover them. Pierre Bergé, Yves Saint Laurent’s business and life partner, would pick Mr. Fairchild up himself at the airport when he came to Paris. No chauffeur-driven ride would do. And Saint Laurent always gave Mr. Fairchild an exclusive private preview of his collection. For some (Bill Blass, Saint Laurent, Oscar de la Renta), Mr. Fairchild was a kingmaker. But many others (Geoffrey Beene, James Galanos, Pauline Trigère) had long-standing feuds with him, and their careers suffered because of it.

He was cruel and vicious to the late Marie-Hélène de Rothschild, the undisputed social queen of Paris. Marie-Hélène, always elegantly dressed in Saint Laurent or Valentino couture, suffered from a rare debilitating disease, resulting in crippled and deformed hands. It was savage, his personal revenge. Maybe she snubbed Mr. Fairchild at some grand Paris social gala; who knows? For his revenge, he had her body printed on page 1 of WWD, with her face airbrushed out and her deformity in clear view.

During my first few weeks at WWD, I was receiving handwritten letters from Karl Lagerfeld in Paris almost every day. We had bonded during our interview and now kept in touch regularly. Surely that would have gotten Mr. Fairchild’s attention, but still, he did not acknowledge my presence.

Finally, nearly two months after I’d started, Mr. Fairchild started asking me about who I’d seen the previous night, what parties I had attended. He eventually realized I had something to offer and could analyze, report, sum up, and write clean copy, fast. I had no choice. We had daily issues, and content needed to be generated to fill the pages. It was a major newspaper under the leadership of John Fairchild, who had inherited it from his father.

“I am the boss, and don’t you ever forget it,” Mr. Fairchild once said to me as we sat together on the front row in Paris, during haute couture. While he could be intimidating and threatening, I still had so much respect for him. He taught me how to analyze the beat of fashion and the rhythms of the high rollers, the social doers and achievers of the fashion battlefield. “I don’t give a damn about clothes, I care about the people who wear them,” was a phrase he oft repeated. From him I learned how to embrace what was going on around me in 360 degrees. What makes a beautiful dress? Hems, seams, the way it’s put together. The ruffles. How’s the ruffle? How’s the bow tie? What’s the combination of colors, what’s the combination of fabrics? There’s Mounia on the runway, in what? What was Yves’s inspiration? What is the music behind her? And what is the chandelier behind her? And there are roses, why are they there? Why is she wearing that shoe? And what is the lipstick? What is going on in the mind of the designer? That’s my role, taught to me by Mr. Fairchild.

There was no set standard of writing style at WWD, not like The New York Times with its manual that all reporters had to follow. We wrote at a brisk pace, hoping it was all up to Mr. Fairchild’s standard. People at WWD were thrown in the tank and sank or swam, and I just happened to swim.

My first reporting assignment was to cover a party given by Diane von Fürstenberg. She was married to Prince Egon von Fürstenberg. They were the current “it couple,” appearing on the cover of New York magazine. I stood outside of her apartment, having not been able to score an invite to the actual party, along with a bunch of other journalists and photographers. I wore a silver asbestos fireman’s jacket as an evening topcoat as I jotted down the names of all the various people going into the party. I recognized almost everyone; that’s the kind of knowledge I’d gained from reading every issue of Vogue since I was a child.

I soon made it from the sidewalk to the sitting rooms of the plush homes of the fashion elite as they began inviting me into their parties. New York Times fashion editor Bernadine Morris wrote about my attendance at a party thrown by Calvin Klein: “André Talley, reporter for Women’s Wear Daily, wore white Bermuda shorts with a striped high-collared Victorian shirt. Mr. Talley kept telling people that the initials on the pocket were not Kenneth Lane’s but Karl Lagerfeld’s.”

It was the first time my name appeared in a fashion column.

I assume my Southern manners were considered appealing, paired with my knowledge and sense of style. Halston had already gotten to know me quite well from my time at Interview, and he invited me to his house often. He dressed me in his beautiful old castoffs, as I was tall and thin, with the same measurements. Thanks to Halston, I had incredible cashmere sweaters, summer smokings, and five or six Ultrasuede safari jackets that could be thrown in the wash and come out of the drying machine looking perfect, no wrinkles. Halston even sent over an antique Chinese chest, which I used to decorate my room at the Twenty-third Street Y.

Mr. Fairchild saw in me, as Mrs. Vreeland saw in me, that I loved fashion. And for that, a great deal is owed. And after being assigned to write about the legions of friends of Mr. Fairchild, I started to become friends with many of them myself, including the de la Rentas, who took me under their wings like I was an orphan child. When Oscar de la Renta presented his collection, in his narrow showroom, I would be seated on the front row beside Françoise (his first wife). On the other side would be the guest of honor, Diana Vreeland one season, Pat Buckley or Nancy Kissinger another.

During an August resort collection, Françoise turned to me and said, “Now, DéDé, you know Oscar and I are going to build a pool at our country house, in Kent, Connecticut. Don’t you want to be invited to swim in that pool when it’s completed?”

I smiled politely as though I hadn’t quite heard her blatant quid pro quo over the preshow musical arrangement. I never shared that exchange with Mr. Fairchild. The de la Rentas would have suffered.

Mr. Fairchild fueled his viciousness with the details of the parties his editors had gone to the previous evening. I once told him Maxime de la Falaise, a French high society transplant, had complained that Oscar and Françoise de la Renta’s shih tzus had remarkably bad breath. Mr. Fairchild immediately went to his desk and phoned Françoise, to share what I had just told him.

This caused a major scandal. Mr. Fairchild was amused. I got on the phone and told Maxime what had happened, and she asked me what to do. I told her to call Mr. Fairchild directly and ask him what to do. He recommended Maxime send along something special, like her homemade preserves or jelly. She did, and the whole thing cooled off.

I still went out with Andy Warhol sometimes, but I would never tell Mr. Fairchild. He would have been livid. The friendships I made at Interview proved useful and beneficial for Mr. Fairchild’s paper, however.

Bianca Jagger was in New York and invited me to see her at the Pierre hotel. With her was Betty Catroux, one of the permanent icons in the pantheon of Saint Laurent androgynous style. The three of us talked while Bianca ironed her Valentino couture clothes on a board set out between the two twin beds in her room.

The next time Betty came to New York, she called and asked if I’d go shopping with her after lunch. Shopping with the Betty Catroux, the woman who inspired Saint Laurent’s pantsuits? How glamorous.

Or so I thought.

“Meet me at Woolworth’s, I have to buy T-shirts,” Betty said.

As we strolled the Woolworth aisles, I discovered the same hairnets my grandmother wore. Three for twenty-five cents. How fantastic, I thought. World-renowned Betty Catroux, who could freely wear whatever finest-quality designs she wants, buys her clothing from the same place my grandmother buys hairnets!

“Why on earth do you need these Woolworth shirts?” I asked Betty.

“I have to break down the elements of my Saint Laurent couture suits.”

Totally matter-of-fact. All of the beautiful Yves Saint Laurent couture pin-striped suits, Betty wore with T-shirts she bought as a pack of three. Most women would wear a pussycat-bow blouse, but Betty Catroux couldn’t have cared less about what “most women” would do. It was a very original way of thinking at the time.

Betty met Yves in 1967 and it was like lightning. She loved to tell people, “He cruised me in a nightclub.” It began a close brother-sister bond; Yves and Betty, attached at the hip, were the closest of friends. Never officially on the payroll, Betty abhorred fashion. Refused to be a slave to the rhythm of la mode. She had worked as a cabine model for Coco Chanel herself for two years but hated every minute of it. Of the great lady of twentieth-century fashion, Betty told me, “She was a viper, a mean viper. Yves was also mean, two fashion dictators who found everyone else atrocious.”

Be that as it may, Yves wanted to be Betty Catroux. Once they got together, she forever became Yves’s surrogate and alter ego.

Betty always dressed, impeccably, like a man. Tall and lean, throughout her entire adult life. She has never slipped into a full, sweeping evening dress, as best I can recall. She simply refuses. For the grandest ball in Paris, she would ring up the house of Saint Laurent, as she did every day in Yves’s lifetime, after which a little black van with the YSL logo would arrive at her apartment and drop off the look she’d selected, and the same van would pick up the original sample the next morning. This was her routine every day of her life when cocktail or dinner dressing was required.

Betty Catroux is the ultimate rogue, always in vogue. She never wears color, not even red. No prints, ruffles, or flounces. She loves everything black except for those ubiquitous white T-shirts. If she could wear a black leather jacket or biker-style look every day, she would. No jewelry adorns her neck, nor her ears. Her only great accessories are her long, long sheets of platinum hair, airborne once she hits the dance floor. Betty dances like a dazzling rock star in high-gear performance mode.

At times, her look could be interpreted as somewhat “butch.” Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn had already been credited with creating androgyny, but with Betty, it existed spiritually and sartorially. Yves was inspired by Marlene Dietrich, who had gone to her husband’s Austrian tailor to have her pantsuits made for her. But Yves was more directly inspired by Betty and her effortless, impeccable style. With the master touch of Yves, Betty made the evening or le smoking pantsuit an international and global fashion trend. She was, and remains, one of the most influential personalities in high fashion. So many women and men—gay, straight, gender fluid, and transgender—and designers owe much to the Betty/Yves female-dandy style.

Most of the fashion elite, including the top-tier designers—not the established designers, like Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, and Ralph Lauren, but the new wave of designers—were working, loving, and living on a regular diet of cocaine, then the drug du jour. Everyone was high on coke and cock.

Halston thrived on it. He was known to partake and afterward stay up and change a whole collection overnight. Presto: a masterpiece. I remember billowing, long grand taffeta evening dresses, floating away from the body, worn over Lycra one-piece leotards. The great Scottish photographer Harry Benson shot them for W, and they are some of the finest illustrations of American high style of the era.

If I went to Françoise de la Renta’s house for dinner, and said I had been to Halston’s, she would tell me that was “the wrong crowd.”

She of course was right. Halston used to have me over for dinner, just the two of us, and he would serve a baked potato with caviar and sour cream. For dessert: a small mountain of high-class cocaine served in an Elsa Peretti sterling silver bowl.

I snorted a line or two, to be polite to my host, and that was it. I never wanted to feel out of my sphere of control. My destiny was not to be hooked on coke. I feared God and my “ancestors as foundation,” to quote Toni Morrison, always lived invisibly on my shoulder.

My only addiction was pure Russian vodka, which I usually drank in Diana Vreeland’s red seraglio. We were always two, elevated by conversation, drinking small shots, one after the other, after dinner, in her dining room. I often left her apartment on weekends at three or four or even six A.M.

I managed to master social nuances between the old guard of fashion, like the de la Rentas, and Halston’s new wave of partying. I glided through this world with extreme caution and my usual armor: my fashion choices. Banana cable knee socks and elegant moccasins. Or Brooks Brothers penny loafers. Neckties, my Karl Lagerfeld castoffs, and Turnbull & Asser shirts. I never spent a dime on drugs. My money was spent on luxury. Massive bouts of high-end retail shopping.

In this, Manolo Blahnik and I were kindred spirits.

Manolo Blahnik, the sum total of human genius in designing shoes for women, invited me to Fire Island one weekend. He arrived with matching sets of Louis Vuitton cases, filled with matching sets of tone-on-tone Rive Gauche shirts and custom-made linen trousers. If he wore a cerulean shirt, he had cerulean linen oxfords. If he wore a geranium-red silk Mao Rive Gauche shirt, then he of course wore matching Fred Astaire linen oxfords.

We went to a pool party where they spiked the punch with something, causing us to have nonstop fits of laughter for nearly fourteen hours. We took a walk along the beach, he in his matching look, me with a big panama hat, a huge Japanese parasol, and a black and white oversize cashmere blanket, wrapped over me like a pareo. We were quite the pair.

The half-nude men in thongs and Speedos near the surf kept screaming at us, laughing at us. “Get off the beach, you faggots. This isn’t the beach for you!”

Next we sauntered off to the woods, as we heard that was where men gathered in full view, to have group sex. There, under a tree, was a circle of men wearing leather chaps and nothing else, participating in group masturbation. It made us both burst out giggling, which caused the participants to boo and hiss at us until we left.

While I enjoyed checking out the scene under the influence of whatever I had been exposed to, when it came to sex, I was repressed. It was a conscious choice I had made. Sex confused and bewildered me. In respectable Southern black households, it was simply not discussed. Physical intimacy of any kind was kept to a bare minimum. I can remember only two times in my childhood when my grandmother hugged me: The first time, in my early teens, was when I had an asthma attack. Then once again, when I was sick, lying on the sofa, she walked over and pulled up a throw blanket to my neck, and hugged me. Mama was not demonstrative of her love, not on a daily basis. She was loving but also stoic, strict, and severe. Too busy washing, ironing, preparing chickens, doing all the daily routines of a humble domestic maid who was also, in essence, a single mom to me.

I grew up with no inkling of what physical intimacy was, my parents long divorced and my grandmother widowed. My interior monologues about romance and love were confused. My only crush, like many others’, was on Anne Bibbie, our high school homecoming queen. While I was in college and at Brown there was no one, no sexual interludes. But in New York sex was impossible to ignore; everyone was doing it and everyone was talking about it. And that forced me to come to terms with something I had long tried to forget.

During my childhood years, my innocence was shattered by a man who lived on the next street. His name was Coke Brown, or at least that was his nickname in the neighborhood. He lured me into the woodshed, directly underneath my wood-framed house, in the damp, dark earth, where he proceeded to take advantage of my youth and my naïveté when it came to sexual encounters. Afterward, as he zipped up his fly, he said, “This is our secret game.”