The Chiffon Trenches

At Brown I studied the culture of France, the brilliant, intellectual bohemian lifestyle of the nineteenth century, Charles Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine. I felt free, no longer restrained by the rigid, judgmental community I had grown up in. Now that I was out in the world, I didn’t give a damn what anyone thought about me. I wore a vintage surplus navy admiral’s coat, in perfect condition. All the brass buttons were intact. It was a maxi, almost to my feet, and I’d wear it with scratchy sailor pants—four inches above the ankles—and lace-up oxfords with small flamenco-dancer heels.

During the first winter break, I brought the coat home to North Carolina. I was so proud of that coat. My grandmother could not have cared less, but my mother refused to attend church with me while I was wearing it. As we got out of my cousin Doris Armstrong’s car—she always drove across town to pick us up and take us to our country church—my mother held me back.

She glared at me and said, “I can’t be seen walking with you up the aisle in this Phantom of the Opera look.”

“Go ahead,” I said. I waited outside a few minutes while she went in, smarting from her comment. My mother could be quite nasty to me, but I still respected her. That did not mean I had to like her.

I was a fashion addict, dramatic in attire and appearance, even then. I would wear kabuki makeup like Diana Vreeland, legendary Vogue editor in chief, or Naomi Sims, the first black model I ever saw in Vogue. On any typical day, I would layer Estée Lauder’s latest shade of deep grape on my temples, top it with Vaseline, and head off to class.

My wardrobe caught the attention of affluent students at the Rhode Island School of Design, also located in Providence. I began to live two separate lives: the one on campus for my studies at Brown, and the one at RISD, where I made friends with Jane Kleinman and Reed Evins. Jane’s father was then head of Kayser-Roth hosiery, and Reed’s uncle was David Evins, the shoe magnate. They lived off campus, in a big floor-through apartment filled with sunlight and incredible antiques. Reed came to RISD with a huge van of furniture. There were Chippendale dining room chairs, a beautiful mahogany leaf dining table, Baccarat glassware, sterling flatware, damask tablecloths, and beautiful china with gold-leaf borders.

One weekend, Jane went home to New York City and came back to school with a Revillon skunk coat purchased on sale at Saks Fifth Avenue. She was so proud of that coat. It was the exact same coat Babe Paley owned, South American skunk—Chilean skunk, in fact. Diana Vreeland’s favorite!

Reed and Jane ruled: They seemed to have it all—the best clothes, the best furniture—and they were New Yorkers. On my birthday in October 1974, they brought me to New York to attend the Coty Awards fashion show, at FIT. I don’t remember anything about the show, except meeting Joe Eula, who was an important illustrator for Halston, then the hottest designer in America. Joe Eula invited me to a party at his house after the show, where I met Elsa Peretti, as well as Carrie Donovan, with whom I had corresponded years earlier.

Carrie was a madcap and very talented fashion editor, a cross between Kay Thompson in Funny Face (the best fashion comedy film ever) and Maggie Smith in a movie that won her an Oscar, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. I absolutely adored Carrie’s boutique pages at the back of Vogue.

I walked up to Carrie Donovan and introduced myself. “You wrote me a letter,” I said, and reminded her that I had written to Vogue, inquiring as to who had discovered the model Pat Cleveland. Carrie had written me back and said it was she who had discovered Pat Cleveland on the Lexington Avenue subway, traveling to work one morning. The note was brief but beautiful, typewritten and signed in electric-green ink.

Carrie was warm and gracious, and told me to stay in touch. “And if you want to work in fashion, you have to come to New York,” she said.

As soon as I arrived back in Providence, I made plans to abandon my studies at Brown and move to New York. I already had my master’s but was working on my doctoral thesis, with plans to become a French teacher. While I’d been recommended for teaching positions at private schools up and down the East Coast, I was unable to procure a job. I was eager to see what awaited me in New York and in the world of fashion.

Reed had finished his studies at RISD and already moved back to Manhattan. He offered to let me stay with him until I got myself situated. In one large soft Louis Vuitton zipper satchel, I packed my most precious items: my navy coat, two pairs of velvet Rive Gauche trousers, two silk Rive Gauche shirts, and my first bespoke black silk faille smoking shoes, custom-made by Reed Evins himself. They were blunt-toed slip-ons, lined in flaming red.

Jane Kleinman’s father wrote me a letter of introduction to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Diana Vreeland was hiring volunteers to assist with her curation of an epic exhibit: Romantic and Glamorous Hollywood Design.

The letter worked and I was hired, with no salary. I didn’t care; I was going to meet Diana Vreeland, the grandest and most important fashion empress! The famed editor in chief of Vogue for almost ten years! Considered to be one of the great fashion editors of all time! Running the Costume Institute was Vreeland’s dream job and my own dream apprenticeship. It was highly selective; there were only about twelve of us.

My first day as a volunteer, I was handed a shoebox filled with metal discs and a pair of needle-nose pliers.

“Fix this,” I was told.

“What is it?”

“It’s the chain mail dress worn by Miss Lana Turner in The Prodigal. Mrs. Vreeland will be here shortly to inspect your work.”

Left to my own devices, I laid out all the pieces and quickly figured out the complex puzzle pattern. Eventually I was able to craft the shoebox of metal back into a dress.

“Who did this?” Mrs. Vreeland asked.

“The new volunteer.”

“Follow me,” she said, and I did. We went into her office, where she sat down and wrote my name in large letters. “HELPER,” she wrote underneath it, and handed the paper to me. “You will stay by my side night and day, until the show is finished! Let’s go, kiddo. Get crackin’!”

Mrs. Vreeland spoke in narratives, in staccato sentences. You had to figure out what she wanted. The next dress she assigned to me was from Cleopatra, worn by Claudette Colbert. “You must remember, André, white peacocks, the sun, and this is a girl of fourteen, who is a queen. Now get crackin’! Right-o!”

It was a gold lamé dress. I spray-painted the mannequin the same color gold.

“Right-o, right-o, I say, André!” Mrs. Vreeland responded.

Over the next six weeks I became one of Mrs. Vreeland’s favorite volunteers in what was really like a fine fashion finishing school. Through Diana Vreeland I learned to speak the language of style, fantasy, and literature.

I listened to and I learned from Mrs. Vreeland. I hung on her every word, every utterance. I towered above her physically, but I was utterly respectful and properly reverent, and she in turn treated me with great respect.

In 1974, my first year in New York, I was a volunteer for Diana Vreeland at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute. She and I spoke the same language of style, fantasy, history, and literature. Here we are assigning silver hairnets from Woolworth’s to cover what Mrs. Vreeland called the “hideous” faces of the mannequins.

Photograph © The Bill Cunningham Foundation. All rights not specifically granted herein are hereby reserved to the Licensor

She must have loved the idea of my presence, the combination of my looks, tall and honey colored; my impeccable manners and grooming; and my blossoming unorthodox style. Plus my master’s degree!

After the exhibit’s opening night in December, I needed a job. I tried working as a receptionist at the ASPCA but it was too tragic. Mrs. Vreeland called me into her office late one afternoon, just before taking off for the Christmas holiday season.

“Don’t go home to Durham, André!” Vreeland pronounced. “If you go home to the South, you will get a teaching job of course, but you will never come back to New York. It will happen for you, just sit tight and don’t run home.”

“But I have no money, I need a job!”

“Stick it out! You belong in New York. Do not go home for Christmas!” With that I was dismissed, and she was off to the beautiful home of Oscar and Françoise de la Renta in Santo Domingo.

Christmas Eve 1974 turned out to be one of the darkest nights of my life. I had no money, and I was sleeping on the floor of the studio of my friend Robert Turner, a fellow volunteer. He was out of town for the holiday. I slept on a horse blanket, found at a local thrift shop, and a borrowed pillow from his platform bed. There was nothing left in the refrigerator and not one cent strewn around for a greasy hamburger.

I opened the cupboards and found a can of Hershey’s chocolate syrup, which I devoured with a fine silver teaspoon and followed with glasses of water to chase the thick, dense syrup down.

The phone rang at ten P.M. It was my grandmother.

“Ray”—she never called me André—“your father is here next to me. I am sending him to drive through the night and bring you home. You need to be ready, because he will be there tomorrow, on Christmas Day. You come home. You belong home. You have never been away from home at Christmas.”

I insisted I wasn’t about to come home. Mrs. Vreeland had said it would happen for me in the New Year! Mama hadn’t put up an argument when I left for Brown; why was she so adamant now?

So I asked her, “Why? Why do you want me to come home so urgently?”

Silence. Pause. Then she shouted into the telephone: “Come home, because I know you are sleeping with a white woman up there!”

That was the furthest thing from reality. I laughed out loud and assured her this was not the case. She uttered something and hung up the phone. I knew she was upset, but I had faith in Mrs. Vreeland.

During that long and lonely Christmas week, I visited Saint Thomas, an Episcopal church, often. There I would meditate and pray for my parents and my grandmother, and thank God for the gifts and opportunities I had been given. I was grateful to be in New York, even if my future was uncertain. I was confident that my faith and my knowledge would see me through, even if my stomach continued to rumble.

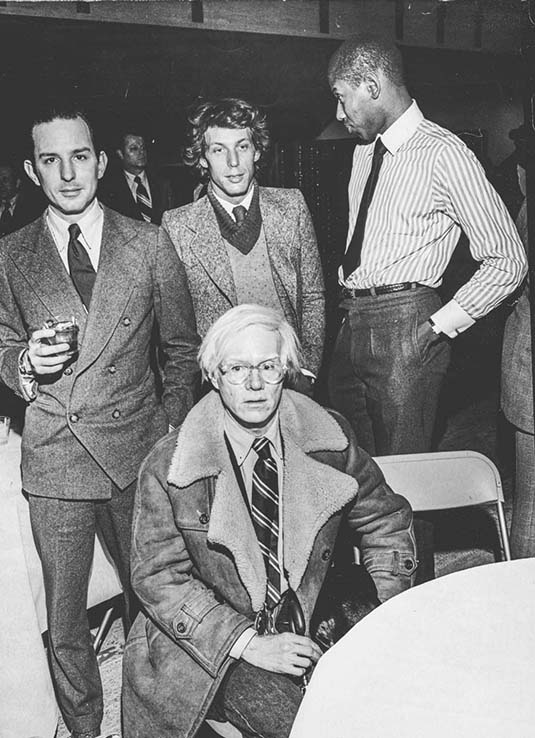

All staffers of Warhol’s Factory and Interview magazine: Fred Hughes, Peter Lester (center), and Andy Warhol, seated at a Halston fashion show in 1975.

Photograph © The Bill Cunningham Foundation. All rights not specifically granted herein are hereby reserved to the Licensor

II

First thing in January, Diana Vreeland wrote letters on my behalf to every important figure in fashion journalism. Like a trumpet, with her booming voice, she built me up to everyone. Halston, Giorgio Sant’Angelo, Oscar and Françoise de la Renta, Carolina Herrera, all her friends; she never let up speaking on my behalf.

She also made sure I was invited to all the right parties, including Halston’s legendary soirees, attended by anyone who was anyone in New York: Liza Minnelli, Martha Graham, Bianca Jagger, Elsa Peretti, Diane von Fürstenberg, and the entire Warhol upper echelon. I was there one night with Tonne Goodman, another favorite volunteer of Mrs. Vreeland’s and a well-connected New Yorker herself. As we dragged along the pale-carpeted floors, Fred Hughes, right-hand man and business partner to Andy Warhol, came up to me. “André, do you think you could come to the Factory and meet with Andy and Bob? Diana Vreeland says we must have you work with us.”

I of course said, “When do you want me? I’ll be there.”

The following Monday, I began my career as an assistant for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. I moved off my friend’s floor and into a small room at the Twenty-third Street YMCA, where I battled numerous cockroaches in the public showers, real ones and human ones.

Interview was a lean office, adjacent to the big Factory space, where Andy’s loyal staff worked at a long makeshift desk in the open reception area. There was the elegant boiserie-paneled boardroom, where Andy took his lunch. His workspace, or his artist’s studio, was the entire length of the floor, divided by a wall just behind the Interview offices.

Fred Hughes set the tone. He was the sum total of elegance, with hair like Tyrone Power and a definite snobbish Continental accent. Diana Vreeland loved him, and it was rumored that she considered him her beau.

The space was clean and light filled. Huge Jean Dupas art deco posters hung throughout. The whole atmosphere was lighthearted, but in a serious kind of way. We were expected to be at work on time and no one spent hours on the telephone social networking. My job was really just to be a glorified receptionist, buzzing visitors through the bulletproof steel door Andy had put in and taking messages for all the freelance talents. My duties, which included picking lunch up for Andy at the local health food store Brownies, started at twelve noon and ended at six P.M.

Everyone was freelance, so people were always coming in and out and you never knew who you were going to see on any given day. Fran Lebowitz made regular appearances. Her major bestseller, Metropolitan Life, had just come out. She’d walk in, very serious, chain-smoking, and ask for her messages. She was intimidating. A great intellect and succinct in verbal sparring.

No one messed with Fran. Not even Andy. Everyone was afraid she would torch the place. Metaphorically. Her grumpiness was part of her façade. Fran praised me, saying I was the only receptionist who took the job seriously and actually wrote down accurate messages.

Fred Hughes liked having society ladies flitting about the office, not doing much of anything. They served as ornamentation. Catherine Guinness, of the Guinness beer fortune, was working on a piece exploring the underworld of sadomasochism with her gay friends. She would wear leather jackets to the office, playing around with whips and things like that.

Fred always wore bespoke everything, including tennis-stripe jackets and skinny jacquard silk ties. His shoes were polished, the way English dukes polish the same pair of shoes for decades until they become like soft gloves for the feet. Fred’s apartment was decorated with first-rate antiques, and he let his house become a bed-and-breakfast for all the young ladies who wanted to be part of the scene. Some would stay indefinitely. Everything was kept in a state of pitch-perfect perfection, including Fred’s highbrow fake English accent, hysterical considering he was from Houston, Texas. His mannerisms, his dandyisms, his snobbism were toxic to my budget but auspicious for my aspirations.

Casual dress was the regular uniform, which made it easy for me to create a distinctive imprint. I wore fine vintage topcoats, found in a local thrift shop on Fifty-fifth Street for ten bucks, and tweed trousers, never jeans, as I never felt comfortable in a pair of jeans.

Mrs. Vreeland would often take a taxi down to the Factory for lunch. On those days, sandwiches would be ordered from Poll’s on Lexington Avenue: chicken on brown bread, and a small shot of Dewar’s for Mrs. Vreeland, her healthy tonic. Just a shot glass at lunch and that was it. It was a different time.

One day, Mrs. Vreeland came to the Factory with Gloria Schiff, a great beauty and twin sister to Consuelo Crespi, Italian editor for American Vogue. I overheard them having a highly pitched debate: “Gloria, what do you mean you discovered Marisa Berenson at a debutante ball!” exclaimed the imperial Vreeland. It was, in fact, Vreeland who had put Marisa Berenson on the map, having seen her at Elsa Schiaparelli’s house in Paris! Elsa was Marisa’s grandmother, and Elsa never forgave Mrs. Vreeland for introducing her to the world of high-fashion modeling.

For all that I made seventy-five dollars a week; the social life that came along with it was surely priceless.

When it came time to assign fashion stories, I was the go-to fashionista in the office. My knowledge and passion in this area were recognized and I was quickly promoted to fashion editor. I now had the opportunity to interview some of the most exciting stars of society, fashion, and international jet-set acclaim, including Carolina Herrera, the elegant designer from Caracas, Venezuela, who later dressed Jackie Kennedy when she lived in New York. I did Carolina’s first official interview, in a lavish spread.

Bianca Jagger was my favorite stylish subject. It was her time; she had wed Mick in the south of France, wearing an Yves Saint Laurent suit and a sweeping portrait hat with a veil. The Rolling Stones were playing at Madison Square Garden and Andy sent me to the Pierre hotel to pick up Bianca, and her wardrobe, and bring them to the studio to be photographed for a cover. Bianca answered the door and motioned to me to walk quietly. Mick was asleep. We tiptoed around the rock star to the huge walk-in closet off the bedroom suite. Quietly, we piled up her beautiful clothes and her favorite shoes that season, Charles Jourdan espadrilles on a high wedge sole. She had a half dozen of that same ankle-wrap wedge platform sole, in an array of colors.

All of this was packed in tissue and layered in extraordinary Louis Vuitton cases, unlike any I had previously seen. They were actually custom-made hunting cases, used to pack guns for grouse shoots. Because of the length, she could pack her Zandra Rhodes crinoline evening gowns flat, no folds, in these coffinlike cases. She had bought them in Paris, at the avenue Marceau Louis Vuitton store.

Bianca and I took a taxi, piled high with her Vuitton luggage. We bonded over our deep admiration for her friend the shoe designer Manolo Blahnik, and we went on to become friends.

When it came to having access to the elite echelon, Andy provided it, taking me everywhere I wanted to go, from dinners at Mortimer’s to movie premieres in subway stations. I met everyone at some movie premiere—C. Z. Guest, Caroline of Monaco, Grace Jones, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

With Andy, anyone could be anyone and everyone was equal—a drag queen or an heiress. At the Factory, if you were interesting, you were “in.” And while he could be seen out and about at night, Andy also went to church every morning to thank God for his life, his money, and his mother.

Andy could be naughty. He could also be vicious, but never to me. From time to time he would put his pale white hands in my crotch (always in public, never in private) and I would just swat him away, the way I did annoying flies in summer on my front porch in the South. Once, we went to see an afternoon movie with Azzedine Alaïa on the Upper East Side and Andy kept grabbing me. Every time, I would scream out, “Andy!” Azzedine was in hysterical tears. Andy was naïve; nothing he did offended me. He saw the world through the kaleidoscope colors of a child. He was a kind person, and I considered him a very dear friend, too.

When Andy was in a good mood, he created small, signed pieces of art for his staff. A silkscreen print from one of his series, or a small painting, like a candy heart in lace on Valentine’s Day. It was a quite generous perk.

While creating his so-called Oxidation paintings, aka the “piss paintings,” Andy asked me to participate.

Instantly I said, “No thank you, Andy.” All I could think of was my grandmother, or my mother, or father, hearing about me. Peeing for art? It would have broken Mama’s heart to think that although I was living a successful, adventurous life in New York, I was spending my time creating paintings with urine.

Andy also asked me to participate in the Sex Parts paintings. We were in Interview editor Bob Colacello’s office and Andy said, “Gee, André, just think, Victor Hugo is doing it. You could become famous, make your cock famous. All you have to do is let me take a Polaroid of you peeing on the canvas. And I will give you one as a gift.”

Victor Hugo the writer is not whom Andy was referring to, but rather Victor Hugo the male escort, who was Halston’s lover. Handsome, from Venezuela, notoriously well-endowed, and possessed of beautiful skin, he was also a window display artist for the Halston boutique and had apparently now somehow gotten a gig at the Factory, doing these outpourings of overt sexual exploration.

Was his name really Victor Hugo? No, of course not. There was nothing really remotely Victor Hugo about Victor Hugo. He never quoted the literary giant. He never spoke about him. He didn’t subscribe to literary brilliance. But he did piss on a canvas for Andy Warhol, and his penis did indeed become famous.

Andy loved hanging around with Victor and often included him in his Factory workshop life. I knew him well, but I was not witness to his thrusting full, erect penises into his mouth in a working session with Andy, while others were going about their duties, putting out Interview.

As ghastly as it seemed, at some point Andy did indeed elevate pornography, or pornographic interests, through Victor Hugo. (For the record, I have no doubt: Andy never had sex with Hugo, except with his Polaroid and his art.)

Victor invented himself as an artist, as a disrupter, as a unique individual in New York’s cultural mix. One of his Halston windows featured a hospital tableau, with a woman giving birth in a Halston dress. He once had a live chicken dipped into liquid the color of blood and left it alone to walk along the corridor, the white-carpeted corridor, of Halston’s East Side Paul Rudolph townhouse. Just to “shock” Halston. It worked; he was shocked.

American designer Norma Kamali worked on Madison Avenue and befriended Victor. He would pass by nearly every day. One day, Norma was draping a new swimsuit; the next day, the design had been leaked and ended up as a Halston original on page 1 of Women’s Wear Daily. Norma confronted Victor, who responded like a naughty child, caught doing something forbidden.

Later, he was forgiven: Victor arrived in Norma’s studio with a gift—huge surplus silk parachutes. She skillfully turned them into high fashion, jackets, shirred trousers, ball gowns, and jumpsuits, with the pull releases intact. Diana Vreeland later insisted they be included in her Vanity Fair Costume Institute exhibit. Norma turned defeat into victory!

One night around this same time, Reed Evins and I were houseguests of Calvin Klein at his home on Fire Island, in the elegant Pines section. We ended up sharing a bed, and as we were falling asleep, Victor came in and crashed on top of us. Uninvited. He fell asleep like a bear in winter hibernation. Reed and I, curious about the legendary size of his penis, pulled back the white sheet and exposed the family jewels, which Reed described as the size of “a Schaller and Weber salami.” It was uncircumcised is all I remember. That night, we slept with Reed in the middle, Victor on one end, and me on the other.

In 1975, Karl Lagerfeld was already head creative designer at Chloé and perched to take his place at the top of the fashion world. Chloé had been a staid, bourgeois house for housewives who could afford good ready-to-wear in Paris. After Karl got there, Chloé became extremely influential. Grace Mirabella, who had replaced Mrs. Vreeland as editor in chief of Vogue, was married in a Chloé white turtleneck blouse, embroidered with pearls. That was a big thing—to pick a Chloé look, as opposed to an Yves Saint Laurent.