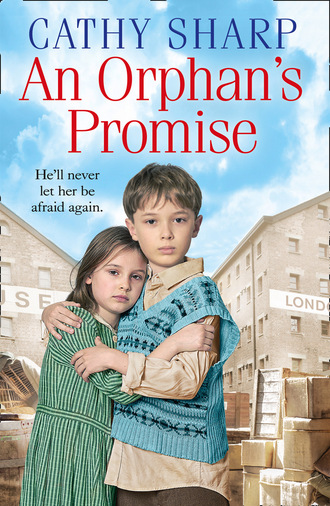

An Orphan’s Promise

‘Dora is certainly afraid of Mr Swan and cannot be allowed to return to them,’ Mary agreed. ‘So, Dora gets priority and that means Charlie and his sister stay here for the time being?’

‘Unfortunately, that is the best I can come up with for the moment,’ Lady Rosalie apologized. ‘I only have one set of approved parents on my list right now – as you know, I am particular about who I take and that means there is sometimes a shortage, but unlike some others I will not place children in homes that might prove unstable.’

‘Indeed,’ Mary agreed. ‘You only have to look at Dora – she was placed with the Swan family ten months ago when her mother died and she has already been into the infirmary with injuries twice.’

‘Well, Mr and Mrs Phillips are decent people. They’ve been waiting for a long time because they wanted a baby, but I have persuaded them to take Dora – they might take Maisie too but they couldn’t manage Charlie as well.’

‘Oh, we mustn’t split them yet,’ Mary said. ‘I see plenty of children in my capacity as matron and they have not been treated as badly as some, despite Charlie’s bruises. I believe Maisie when she says her mother loves her and looks after her; the problem is this man the mother has taken in.’

‘It so often is when the father is dead,’ Lady Rosalie said and nodded. ‘So, I can take care of Dora for you – but you keep the other two until we see if their mother is likely to recover. After all, Maisie’s chest still needs treatment, doesn’t it?’

‘Yes, she could do with a week or two in bed with my nurses caring for her – he ought to be at school, of course, but perhaps they will send some work in for him to do. I think the pair of them might run off if I tried to split them up.’

‘Then we’ll leave it at that,’ Lady Rosalie agreed and stood up.

‘Do yer reckon that Matron is goin’ ter put us in an ’ome?’ Maisie asked as Charlie drank the hot milk one of the nurses had brought them to help them sleep. ‘I don’t want ter go in no ’ome …’ Tears welled in her eyes, running slowly down her cheeks.

‘Yer ain’t goin’ ter,’ Charlie said and set his mouth in a grim line. ‘I promise yer, Maisie. Whatever ’appens, we ain’t goin’ in no orphanage and we ain’t goin’ ter be split up. We’ll stop here fer a while until Ma gets better and then we’ll go ’ome wiv ’er.’

‘Supposin’ that bloke is still wiv ’er?’ Maisie asked looking fearful.

‘We’ll make sure we ain’t around when ’e’s there,’ Charlie said and glared. ‘He ain’t our dad, Maisie, and I ’ate ’im. We’ll go in when ’e’s not there and ’ide when ’e comes.’

‘Yeah.’ Maisie smiled at him adoringly. ‘Yer always know what to do, Charlie. You’ll look after me always, won’t yer?’

‘Yer know I will,’ Charlie said. ‘Me and you – we’re family and families look out fer each other.’

‘I know,’ Maisie said and smiled trustingly. ‘I wish Ma would get better soon, Charlie.’

‘So do I,’ he replied. ‘I’ll see what I can find out from the nurses here. That nice Nurse Sarah might find out for us if we ask her.’

CHAPTER 4

‘These are your new foster carers,’ Lady Rosalie said to the little girl standing just behind her and clutching at her skirt. ‘This is Mrs and Mr Phillips – and they will take good care of you now.’ She reached round and gently pushed Dora forward. ‘Say hello to Mr and Mrs Phillips, Dora.’

Dora’s greeting was a whisper only the most eager ears could hear, but Mrs Phillips bent down to be on her level and held out her arms to her. ‘Hello, Dora,’ she said and smiled at her in a way calculated to win over even a child who had been ill-treated by her last carers. ‘I’m so glad you’ve come to live with us!’

Dora looked at her uncertainly and her bottom lip wobbled. ‘How long will you keep me?’ she asked with tears in her eyes.

‘I want to keep you for as long as you want to stay with me – forever and ever,’ Helen Phillips said. ‘Would you like to call me Mummy or Penny?’

Dora hesitated, then, after looking into the loving eyes of her new carer, she said, ‘Mummy, please …’

Now the tears were running down Mrs Phillips’ cheeks and she bent down to swoop the child into her arms and kiss her. ‘Mummy has a lovely bedroom for you, Dora, darling. There are dollies and a teddy bear waiting for you – would you like to see them?’

‘What’s a teddy bear?’ Dora asked, a look of surprise in her eyes. ‘Is it nice?’

‘Very nice; you can cuddle him,’ Mrs Phillips told her. ‘Shall we go upstairs and see?’ Her eyes met those of Lady Rosalie, who nodded and Helen Phillips departed carrying the child she had waited so long for.

‘I can’t thank you enough,’ Mr Phillips said after his wife had gone. ‘I tried to tell her to accept a small child long ago when we knew we should never have our own – but you persuaded her and it has already made so much difference to our lives. Helen looks happy again …’ His voice broke with emotion. ‘If there is anything I can do to help you, ever …’

‘I may ask you to take another little girl or boy one day,’ Lady Rosalie said with a smile. ‘I can already see you are going to be good for Dora and people like you are not easy to find. I’m very glad your wife decided to take a little girl rather than a baby. It is the slightly older children we really need homes for.’

‘Give us a few months to get the hang of it,’ he said, ‘and then we will be pleased to give Dora a playmate.’

‘I hoped you would say that!’ Lady Rosalie offered him her hand to shake.

‘There won’t be anything we can’t handle,’ he took it firmly. ‘My wife has a lot of love to give a child and I would to anything to make her happy – besides, I’ve always wanted a family myself.’

‘I shall leave you to get to know each other,’ Lady Rosalie said and took her leave. ‘I just wish I could find another hundred couples like you and Mrs Phillips.’

She nodded to herself as she left the neat little home in the suburbs. She would visit the infirmary on her way back and tell Mary about Dora’s new foster parents.

Sarah saw the large car pull up outside the infirmary as she left. She watched the well-dressed woman get out and go inside, pausing for a moment before crossing the busy road. Lady Rosalie was a frequent and well-liked visitor at the Rosie.

On her way down Button Street, Sarah lingered in front of the dress shop and stared at the tartan skirt and the soft wool twinset displayed with it. She could do with a new skirt and she loved that fine knit with fully-fashioned sleeves. They fitted so well and that shade of green would suit her down to the ground. A sigh escaped her, because even though both the skirt and the twinset were reasonably priced at thirty-five shillings, she couldn’t afford to pay three pounds and ten shillings for a skirt and twinset. All her spare money went into the fund that would contribute to their new home.

Walking past the tempting window determinedly, Sarah turned into Shilling Street, thinking about the children that the police had brought in a few nights earlier. She’d asked Matron what would become of them and she had looked serious.

‘We are told that the mother is very ill,’ Matron had said looking sad. ‘It is a pity that she wasn’t brought to us – at least we could have arranged for her to spend some time with her children. If she dies, they will probably have to be placed in an orphanage. I have spoken to Lady Rosalie about it and she is making inquiries. A temporary foster home would be best, since they are neither of them ill. We are not equipped to care for children who are healthy and being idle will lead them into mischief.’

‘Yes, I suppose there is nothing else for them – if their mother dies …’ Sarah’s heart wrenched with pity as she pictured the children’s reaction to such an eventuality.

‘It might be that the Children’s Welfare department feels the mother is not fit to have the care of them, even if she recovers,’ Matron said thoughtfully. ‘I do not approve of taking children from their mothers unless really necessary – but if she is exposing them to a pimp who is likely to beat them …?’ Her shoulders moved in resignation, for such a situation could not be allowed to continue.

‘Yes, I understand,’ Sarah said. ‘I wondered if they had any other relatives other than their mother.’

‘The police knew of none but it might be an idea to ask the boy. He seems intelligent – though a little inclined to aggression and disobedience.’

‘Oh, what has he done?’ Sarah was surprised.

‘He is restless and impatient and he flicked pieces of bread at one of the other boys in the ward. I was forced to smack his leg hard.’

‘Oh dear,’ Sarah said. ‘It’s a shame he had to be punished. I know he thinks he is old enough to work – and if he has nothing to do, he will be bored.’

‘Yes, I am aware of that and it is the reason we must get him settled – either with a foster parent or an orphanage.’

‘He wouldn’t be happy parted from Maisie and I know she is frightened of being put in a home.’

‘I dare say, but we cannot keep them here forever.’

‘Just a little longer?’ Sarah pleaded.

Matron frowned. ‘We’ll see, nurse; I must get on and you have your duties.’

‘Yes, Matron,’ Sarah said and left to get on with her own work, feeling upset. She wondered if Lady Rosalie’s visit to the infirmary had anything to do with the two children and hoped she wasn’t about to send them away to an orphanage.

However, when Sarah called in to see them that evening in the children’s ward, taking a bag of sherbet lemons and some comic books, she found that Charlie was full of what he wanted to be when he could take up an apprenticeship.

‘I’m going to be a carpenter when I leave school next year, nurse,’ he confided. ‘I like throwing pots – that’s what they call it when you make a wheel turn and shape the clay with your hands like this and I learned at school …’ He mimed how he’d shaped his pot. ‘That was fun, but the best was turning a bit of wood on a lathe and carving too. I’ve made up me mind.’

‘Then, perhaps you will,’ Sarah said and smiled at him. ‘Maisie is a little better now – and perhaps your mother will be able to come home soon.’

‘Is she any better, nurse?’ Charlie asked eagerly.

‘I telephoned and they said no change but she was as well as could be expected – so I think that means you just have to be patient,’ Sarah said and saw the disappointment in his eyes. ‘It’s all we can do – wait and see what happens …’

CHAPTER 5

‘We ought ter be at ’ome,’ Charlie said to his sister as they wandered disconsolately about the small garden at the rear of the infirmary. It had a high wall and cherry trees, which were beginning to bud. Matron had sent them out to get some fresh air, but the wind was cool and Charlie was bored. ‘I want somethin’ ter do ’cos I ain’t in school.’

‘That nice nurse what looked after us when we come in brought us some books and that jigsaw puzzle,’ Maisie said. She looked up to her brother, who was four years her senior and the person she cared for most in the world, even more than Ma because Ma wasn’t the same any more and she frightened Maisie. ‘I like doin’ puzzles and the pictures are nice in the books, though the words are hard.’

‘You should ask that nurse who plays with the kids to ’elp wiv yer reading,’ Charlie said. ‘I ain’t got the patience, Maisie. Besides, I should be at work. If I ’ad a proper job I could look after us when Ma ain’t right. I have ter find somewhere we can live and someone ter give me a real job instead of just runnin’ errands.’

‘It’s that horrible bloke,’ Maisie said and two big tears spilled over and ran down her cheeks. ‘Why did yer say we had to pretend we didn’t know ’is name? Everybody knows Ronnie the Greek.’

Most folk who lived in the narrow lanes that bordered the docks knew of Ronnie and his associates. Apart from running a few girls, Ronnie was the hard man for Mr Penfold and, though no one dared to whisper it, Mr Penfold was the man behind much of the violent crime that went on in Docklands. His was the shadow that lay over public houses, small cafés, shops and warehouses that struggled to survive and pay protection money to the gangs that ruled this part of the East End of London; they were an underlife, seen but unreported, ruling by fear and acts of terrible violence against those that rebelled. It was hard enough to earn a living these days and the gangs took much of what honest folk struggled to earn.

‘’Cos, we have ter be careful for Ma’s sake,’ Charlie told her. He knew Ronnie the Greek would squash Ma and them without blinking. The last time the bully had beaten him Charlie had bitten Ronnie’s hand so hard that he’d drawn blood and the bully had yelled and knocked him almost senseless. Charlie knew that the man he hated would as soon break his neck as look at him. He was willing to take his chances, but Charlie loved his little sister and Ma was Ma, whatever she did. Charlie might not approve of the way she went with men for money, but he knew that after his father’s ship was lost at sea, Ma had had it hard. She’d tried honest work but the boss wouldn’t leave her be and she’d been forced more than once before she decided that, if she was going to be a whore, she would be paid for it.

‘I hate ’im,’ Maisie said tearfully and wiped her nose on the back of her hand. ‘I’m cold. I want ter go back inside.’

‘You go,’ Charlie told her. ‘You don’t want ter catch a chill, Maisie. I’m goin’ down the docks ter see if I can find some odd jobs.’

‘You can’t!’ Maisie cried, scared now and looking about her. ‘They won’t let you go and the wall is too high to climb.’

‘I’ll climb that tree …’ Charlie pointed to the cherry tree. ‘I can get up that and over the wall. I’ll be back for tea.’

‘Don’t go – you’ll get in trouble!’

‘If they ask where I am, say I went to the lavvy,’ Charlie said and grinned at her. ‘Don’t worry, Maisie, love, I’ll be back afore they miss me – and if I earn a bob, I’ll bring yer back a penny dip.’

Maisie was silenced. Penny dips, sherbet with either a lollipop or a bit of liquorice to dip in the packet, were her favourite. She watched as Charlie climbed the old tree, balanced on the wall, and then disappeared from view.

Feeling nervous, Maisie returned to the ward and sat on the bed she’d been given. Charlie was so brave. She’d never dare to do the things he did, but he was her big brother and she admired him for his courage. She knew Ma wanted them to go to school but neither of them attended more than they were forced; Charlie because he felt he was old enough to work, and Maisie because she got picked on by some of the other girls if her big brother wasn’t around to protect her.

‘Hello,’ Nurse Anne said, smiling at her. ‘I was just coming to find you. Would you like a cup of hot cocoa?’

‘Yes, please,’ Maisie said. She had taken to the young probationer. Charlie said she wasn’t a nurse yet, just training to be, but she had a lovely smile and she was kind. Nurse Anne didn’t ask where Charlie was and Maisie didn’t tell have to tell her lies, which was good.

She settled down on the bed and looked at the jigsaw puzzle that was set out on an old wooden tray. There were so many pieces and without Charlie’s quick eyes, Maisie knew she might not find any of the pieces that fitted. Charlie helped her do most things, but he didn’t like reading. Maisie wanted to read better than she could and she decided that she would ask the young nurse to help her as Charlie had suggested.

Sighing, she wished that she was as brave as her brother, because she would have liked to be with him, roaming the streets and looking for work. Work was scarce, even for the men who waited in line on the docks or stood on street corners, but sometimes folk would give a willing boy a small job like cleaning windows or delivering something. Maisie suspected that sometimes Charlie took bets to shops and that what he did wasn’t legal, but she never questioned his decisions. Whenever Charlie had a few pennies in his pocket, he spent most of them on her and she wished that the two of them could live somewhere together – somewhere that Ma’s men didn’t get a chance to hit them or leer at Maisie in a way that made her fear, though she did not know what she feared.

‘Nurse Anne is helpin’ me wiv my reading,’ Maisie told Sarah with a little giggle later that evening. She helped herself to one of the precious sherbet lemons the nurse had given them the previous night. ‘How did you know these were my favourites?’

‘I told ’er, you like anythin’ wiv sherbet,’ Charlie said and ruffled her fair curls.

When Maisie was clean, her hair freshly washed, face shining and blue eyes bright with pleasure, she looked like a little angel. Sarah found herself wishing she was in a position to offer these two a home. She wasn’t sure why they pulled at her heartstrings, because many children came to the ward.

Sarah smiled at them. ‘Charlie – do you have any other relatives besides your mother?’

‘Why?’ he asked suspiciously. ‘Ma ain’t dead, is she?’

‘No, but she is very ill and you might be placed in an orphanage because we can’t keep children who are not sick here for long and Maisie is getting better – but if you had an aunt or uncle, they might look after you until your mother is well again.’

Charlie nodded, taking it in. ‘There’s Auntie Jeanie,’ he said slowly. ‘She lives in the country somewhere. Ma said she’s a teacher and her name is the same as ours, ’cos the man she loved was killed in the Great War and she wouldn’t ’ave no one else.’

‘So, she is Miss Jeanie Howes?’ Sarah nodded. ‘And she lives in the country and is a teacher. Well, that is quite a lot, Charlie. Thank you. I’ll tell Matron and perhaps the police might be able to find your aunt.’

‘I want ter be with Ma!’ Maisie whined, on the verge of tears.

Sarah resisted the temptation to pick her up and cuddle her, knowing it was frowned on to make the children dependent on one particular nurse. ‘Yes, of course you do – but you’d rather be with your auntie than in an orphanage, wouldn’t you?’

‘Yeah,’ Charlie said. ‘Aunt Jeanie ain’t bad. Maisie wouldn’t remember – but she came to visit Dad once and she brought me a toy yacht and some sweets.’

Sarah smiled. Charlie was using his brains, working out that they would have more chance of a good life with an aunt than in a home for orphans. Maisie would come round when she saw that her brother was happy with the idea – and unless the aunt was found they might find themselves being taken into care even if their mother lived. Now that it had come to light that she was living with a man who ill-treated her, it was unlikely that she would be allowed to keep the children unless she gave him up …

‘Well, I’ll see what I can do,’ Sarah promised. ‘I’ll come and see you another evening when I’m on duty.’

‘I don’t want to go in no orphanage,’ Maisie moaned when they were alone. ‘And I don’t want ter live wiv Aunt Jeanie. I want ter be wiv Ma.’

‘So do I,’ Charlie said and put an arm about her shoulders protectively. ‘But Aunt Jeanie ain’t bad, Maisie – ’sides, if we don’t like livin’ wiv ’er we’ll run away soon as we’re ready. I’ll soon learn ter be a carpenter and then I can work and keep us both. I give yer me promise, Maisie – I’ll look after yer.’

Maisie’s tears dried as if by magic. Her brother was brave and he could do anything. She wanted her ma bad and when she lay in bed at night the tears came, because she missed her so much. It wasn’t Ma’s fault that she was in the hospital and they’d been brought here, it was that horrible man. Maisie wished she could stick Ma’s long hat pins in to his body and make him cry with pain the way he’d done with Ma – and all because she wouldn’t do what he told her. Maisie didn’t know what the man wanted Ma to do, but Charlie said it was bad and he said that man deserved to be punished. Maisie wished he would die.

‘Here, ’ave another sherbet lemon,’ Charlie said, ‘and stop snuffling. Ma might get better and then she’ll come and fetch us.’

‘Not if that horrible bloke is wiv ’er,’ Maisie muttered. ‘He told Ma he didn’t want us around no more.’

‘And Ma refused what he said she’d got ter do,’ Charlie said. ‘He wanted her to stick us in the orphanage and that’s when she refused and he hit her again and again. I tried to stop him, Maisie, but he just knocked me down and by the time I could think straight, he’d gone and left Ma lyin’ there. I reckon he thought she were dead.’

‘She must be very ill,’ Maisie said, her eyes shadowed with fear. ‘What we goin’ ter do, Charlie? What will they do to us if Ma dies?’

‘If they say we’re goin’ in an orphanage we’ll run away and hide until they stop looking for us. I know lots of places down the docks where we can sleep – and I’ll find work. But if Auntie Jeanie comes, we’ll go wiv ’er until I can look after you.’

‘Could we really do that?’ Maisie asked. Charlie was so brave. He would dare anything and she felt safe when he was with her.

‘Don’t you worry, Maisie,’ Charlie told her. ‘I’ll look after yer. I told yer so.’

CHAPTER 6

‘I don’t know why it upsets me,’ Sarah said when Jim came round for his breakfast the next morning. ‘She’s such a sweet little thing, looks as if butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth, but her brother – he’s made of stronger stuff. I should hate to see them put in an orphanage or split up with different foster carers. You know what some of these people are like – they won’t take two children, and some don’t want boys, because girls are easier. Sometimes they send the girls to one home and the boys to another – they might even send them to Canada or Australia.’

‘You say their aunt lives in the country and her name is Jeanie Howes?’ Sarah nodded and Jim looked thoughtful. ‘Right, I’ll ask in the pub. She may live in the country now, but if the children’s father was a local man then someone will remember the family and they may know where the sister lives. If we can discover the location then the police can probably find them.’

‘You’re a lovely man, Jim Rouse,’ Sarah said. ‘I think I might marry you.’

Jim put his arms around her and hugged her close. She felt a shiver of passion run through him as he kissed her hard on the mouth and knew that he wanted so much more than the touching and kissing they allowed themselves.

‘Now then, no more of that,’ Sarah’s mother said, coming in from the backyard where she had taken some potato peelings to the hens in the run Jim had made for them. They only had three hens but they were good layers and produced several fresh eggs each week. Most of their neighbours looked with envy at the hens but few had gone to the trouble of building a pen and buying their own. Mrs Cartwright didn’t understand why, when times were so hard; the hens ate any leftovers and had cost almost nothing. She’d bought a box of day-old chicks in the market and reared eight of the ten successfully – four had been killed for the pot as pullets but the three hens and one cockerel had survived until this day.

‘I was just telling Jim about those children,’ Sarah said, her cheeks warm, because she knew her mother’s eyes saw all.

‘Proper daft she is about them pair,’ Mrs Cartwright said and shook her head. ‘For two pins I think she’d bring them home to me.’

‘Oh, Mum!’ Sarah laughed and shook her head. ‘I know that’s out of the question. We couldn’t afford to feed and clothe them – and the Welfare would never let us have them anyway.’

‘Time is when I might have thought of offering them a temporary home,’ Mrs Cartwright said. ‘When your father was working full-time, Sarah, he would have taken on any waif or stray that came his way.’

Sarah nodded. As a child, she’d known her father to bring home children who needed a good meal and a bath. Her mother had fed them, cut down some of her husband’s old clothes to fit the lads and taken her own or Sarah’s for the girls. When the children’s parents were over whatever illness or setback they’d endured, they would go home brighter, healthier and usually cheeky. Sarah believed it was her father’s charity that had made her want to be a nurse and take care of those in need.