Полная версия

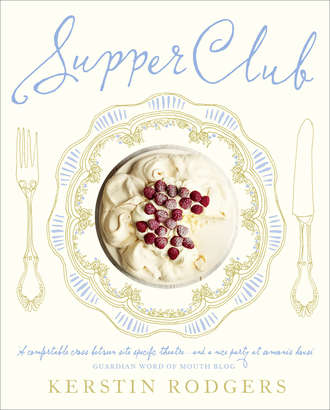

Supper Club: Recipes and notes from the underground restaurant

In a sense, a home restaurant, which celebrates the oldest communal activity in the world – eating dinner together – has been made possible by the Internet, by new media. It’s turning the virtual into the real.

I had been blogging about food for a couple of years before starting The Underground Restaurant. I mentioned in a post that it was about to open and was delighted that some readers immediately requested an invitation.

From the beginning, The Underground Restaurant has been open to complete strangers, people I have never met. Other supper clubs trod more warily, with a long period entertaining friends and acquaintances before opening up to the public. I remember Horton announcing, slightly nervously, on Facebook, two months after opening, ‘This is the first evening that nobody I know will be coming!’

Some supper-club hosts vet their guests carefully. I had problems getting a reservation at one when I booked in my real name, sending at least ten e-mails without reply. When I booked under MsMarmiteLover, I immediately got a reply: ‘You should have said who you were,’ he announced, ‘You would have got in straight away!’ This supper-club host doesn’t want lone diners who ‘make everybody feel uncomfortable sitting there on their own,’ or anybody that he considers would not ‘fit in’. This host is as exclusive as I am inclusive. As I said, everybody has their own style.

Is all this a rejection of overpriced formal restaurants? I liken the home restaurant phenomenon to the punk revolution of 1976. At that time, young people had become frustrated with mega-rich pop stars escaping to America to become tax exiles, hanging out with Princess Margaret on the island of Mustique, and creating concept albums filled with meandering songs. (Pop is, after all, a grassroots movement in which talented people from humble beginnings can ascend the social ladder.) Young people wanted three-minute pop tunes and bands playing local venues for which they could afford tickets. Punk was born.

Most celebrated chefs today are media creatures, for the most part male, and rarely behind the stove of the restaurant that bears their name. Cooking professionally is hard work and long hours, for little pay. Bullying is rife in the industry, both physical and psychological. Even the names, the rankings – chef de rang, chef de partie – have their roots in the army. The glory of cooking in a professional restaurant lies only in repeat bookings and murmurs of ‘My compliments to the chef.’

Like dinosaur prog rockers from the 70s, ‘sleb’ chefs have sometimes turned their backs on the audience. Chefs can make more money from TV shows, cookbooks and endorsed cookware than from their restaurants. Like haute-couture fashion houses, the money is not in the clothes but in the merchandising, the perfume. Like women’s magazines, the gloss and the perfect lifestyle of today’s cookbooks can both inspire aspiration and depression.

For me, my Underground Restaurant is a chance to put into practice some of my political ideals: do-it-yourself culture, making good food available to everyone at a reasonable price, improving the image of vegetarian food. I am probably the only restaurant in the world that reserves cheaper seats for the unemployed, people on benefits, those who may not be able to afford to eat out.

Unlike France, Italy and Spain, there exists a culinary apartheid in Britain. Poorer people are confined to ethnic restaurants, fast food and chains when eating out. London is one of the most expensive cities in the world in which to eat out and most people simply can’t afford to eat at good restaurants. Our food markets, while improving, do not offer the freshness, affordability and diversity of European street markets. A home restaurant in every neighbourhood could be a route to change, raising the status of home-cooked food.

Trust is also important. Many commercial restaurants simply cannot be trusted to provide cooked-from-scratch fresh food or meals for special diets. I cheffed in a ‘vegetarian’ café at festivals that served bacon sandwiches in the morning because they were such a money spinner. The bacon and the vegetarian food were regularly cut up on the same chopping boards, prepared with the same knife. But the fashion for food intolerances can drive the home chef up the wall, too.

Some customers like the idea of exclusivity. Food blogger Krista of Londonelicious describes the appeal for her:

‘I went to Bacchus, but chef Nuno Mendez did not come to the table to personally describe each dish as he did at The Loft. This is way more special.’ This exclusivity comes at a price, though… £120 per head.

Other guests love the idea of illegality, the notion that they could get busted. It’s not so much extreme sport, but the thrill of extreme dining. I have to admit, I do play up this aspect. Guests are asked to memorise a password before they can enter. I tell them that if we get raided by the police, start singing Happy Birthday! (In reality I’ve had policemen come as guests and they don’t have a problem with it!) It evokes memories of the 1920s prohibition era, as does the Argentinean term for underground restaurants, puertas cerradas – ‘closed door restaurants’.

A SUPPER CLUB IS A CHANCE TO CATAPULT YOURSELF INSTANTLY TO THE POSITION OF CHEF/PATRON:

…if you are too old or have too many family commitments to work your way through the ranks.

…if it is too late to go to catering college, to train via the accepted route.

…if you just want to cook part time, want a practice run before you open a mainstream restaurant.

…if you lack the finances to rent a premises, hire staff, enter into contracts with suppliers.

…if you have discovered, like me, rather late in the day, that this is where your heart lies.

Open an underground restaurant. I double-dare you…

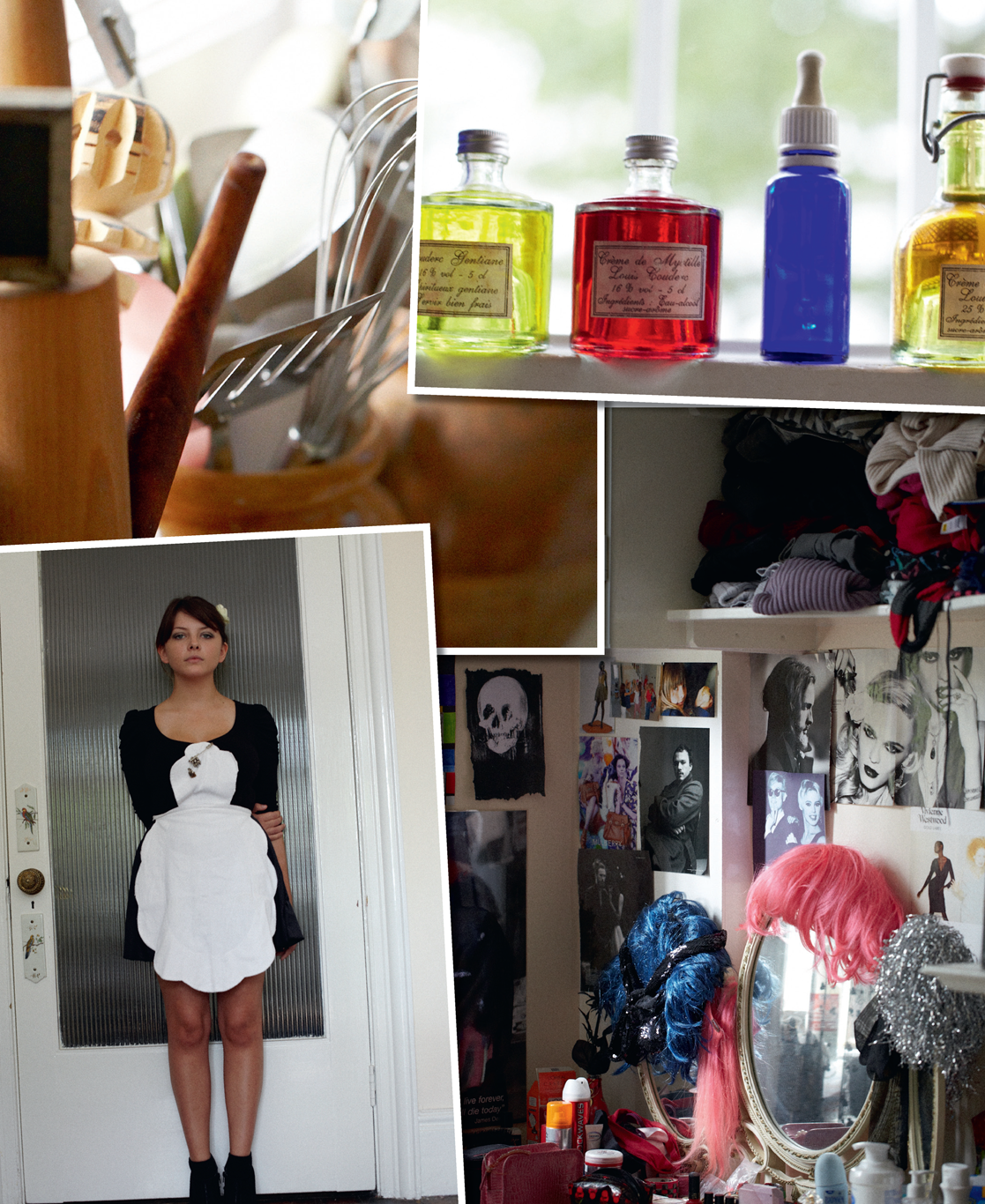

The Story of MsMarmiteLover

I’ve always cooked. I remember the first dish: I was at nursery school and we baked chocolate butterfly cakes. Even all these years later, I remember how incredibly pleased I was with myself. It seemed a magical process. The trick of removing the top of the cake and cutting it in half to make wings was unbelievably cool. I became obsessed with cakes for a while after that. I’d get up early before my parents awoke and get busy cake-mixing. One day I decided to go a step further and turn the oven on. At 6 a.m. my parents awoke to the smell of burning plastic – I’d decided to bake my cake in a red plastic bowl. My mum came downstairs and opened her brand new oven; the red plastic was dripping through the bars of the rack. ‘You can’t heat up plastic!’ she cried. And for a while, that was the end of my baking career.

At the age of eight I was given a copy of Good Housekeeping’s Children’s Cookbook, which gave step-by-step instructions in black-and-white photographs of how to make a cup of tea or toast a slice of bread. Many of the instructions started with ‘First comb your hair…’ From this I learnt how to make macaroni cheese, fudge, peppermint creams and coconut ice.

When I was 15, I got a Saturday job at WHSmith. A new series of magazines had come out: Supercook. As staff, I got a ten per cent discount. Every week, a copy of Supercook was set aside for me, illustrated with typically 70s food photography showing wood-varnished chickens and earthenware pots. The colour brown was big in the 70s. Three months into the subscription, I made a Sunday lunch for the family, from Supercook recipes. As the series was in alphabetic order – a letter a month – I’d only got up to ‘C’, which limited the menu to…Cabbage, Chestnut stuffing, Chicken, Chocolate mousse.

Eventually I got the sack from WHSmith. Not for my punky spiked green and blue hair (to match the uniform, I was pushing the brand!) but for lateness. This meant that my Supercook issues stopped at ‘R’. I could not cook dishes starting with the letter ‘S’.

This didn’t deter me. I hosted a dinner party for a guy I thought fancied me. My menu was sophisticated: grilled grapefruit halves with glacé cherries, spaghetti bolognese (the only thing beginning with ‘S’ that I knew how to cook) and baked apples with custard. I had 12 guests, a ridiculously large amount for a 15-year-old. Grilling the grapefruits took forever and the main course didn’t get served until 11 p.m., by which time I was exhausted and drunk. Then my friend Clare kissed the object of my affection, a cocky guy with a mullet, whose millionaire father owned a plastic-bag factory. Story of my life: I’m sweating in the kitchen, imagining that my beautiful food would attract soul mates, while my friends are outside, wearing platforms, face glitter and flicked-up fringes, getting some action. What idiot came up with that phrase, ‘The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach’? It’s so not true.

When I left school, however, I decided to become a photographer, not a cook. Becoming a chef didn’t seem within the realm of possibilities. TV schedules were not full of cookery game shows as they are now. I loved the Galloping Gourmet and Fanny Cradock, but that was about it. My mum had a boxed set of Elizabeth David books, but there were no photos and I wouldn’t cook something unless it had a photo with it. She also had Robert Carrier cooking cards. These were in a cardboard box, like a file, and each one had a photograph of the dish.

My parents had sophisticated tastes in food. They had a house in France, a wrecked stone cottage with twelfth-century walls that were three-feet thick and a fireplace you could sit in. It was outside a small town named Condom, 100km south of Bordeaux in the Aquitaine region. Every school holiday it took us two days to drive there from London. The route to Condom was devised around recommendations in a red, plastic-bound volume, Le Guide des Relais Routiers de France. It was our job as kids in the back seat to spot the Routier logo. Usually they were proper restaurants, cheap, with a set menu and a parking lot full of lorries. Sometimes, however, you would go into a private house listed in the guide and eat in a woman’s kitchen, just one table covered with a chequered oilcloth. The woman would be wearing her flowery apron and cooking in front of you, turning around from her gas stove to plonk platters down on the table. Once for hors d’oeuvres we were given a dish of long red radishes with their green tops still on, a basket of fresh baguette with a sourdough tang, a small hunk of unsalted butter and a pile of salt. We all looked at it, including my parents, not quite knowing what we were supposed to do with this array of ingredients. The son of the woman, noticing our hesitation, laughed and showed us what to do: he cut a little cross in the end of the radish, smeared on a scrape of butter, then dipped it in salt, crunching the radish with torn-off chunks of bread. So simple, just fresh produce, but so delicious.

Wine was always included and everybody, even children, had a little carafe of rough red table wine. This impressed us kids enormously, we felt so grown-up.

In those days I ate meat. My favourite meal, when we were allowed to order à la carte, was steak and chips. One night near Rouen, we stopped at a hotel-restaurant. We kids, as usual, ordered steak frites. There were strange mutterings from the proprietor; there seemed to be a problem. But then no, it was fine, steak frites it was.

When the steak arrived, I bit into it.

‘What do you think?’ asked my dad.

‘It’s yummy. Sort of sweet.’

‘But you like it?’ he asked, in a rare display of interest in my opinion.

‘Yeah, it’s great,’ I enthused.

At the end of the meal my dad told us that it was horse meat.

So I’ve been brought up to eat well, to eat adventurously. My parents loved to travel even before they had kids; my dad, in an attempt to woo my mum, suggested that they go on a cheap tour of Europe. They hitched everywhere. Their budget was the equivalent of 50p a day. When they arrived in Cologne, my mum perused the menu at a restaurant and chose the cheapest thing. The menu being in German, she had no idea what she would be getting.

The waiter, with a silver-domed platter held high, weaved his way through the crowded restaurant. He placed the heavy silver dish on their table and, with a dramatic flourish, lifted off the lid. There, squatting angrily on the platter, an apple between its teeth, was an entire pig’s head. That was what my mother had ordered.

She gasped.

‘I’m not eating that!’ she exclaimed.

The whole restaurant, having followed the progress of the waiter, burst into laughter.

When things had calmed down, my dad whispered:

‘Don’t worry. I’ll eat it.’

As he commenced tucking in, a smile playing around his lips, my mother breathed out heavily:

‘I think you should know that I’m pregnant.’

It turns out that I was conceived in Minori, Italy, earlier in the trip. My dad, unperturbed, gestured with his fork towards the pig’s head and said:

‘I suppose we are going to have to marry you, then.’

So, as I was growing up, my family travelled through France, Italy and Spain every summer, stopping at Relais Routiers and family-run restaurants en route. Every winter we went skiing, eating fondue, raclette and drinking glühwein in Austria and Switzerland.

Once, my father insisted on taking us to a very expensive and reputable restaurant in Spain, near Malaga. We drove through winding mountain roads for hours to get there. My father ordered the best Rioja wine and taught us to savour its aroma from specially designed glasses. The speciality of the house was the seafood platter, which the waiter displayed in its raw state: it was dominated by a two-foot long sprawling langoustine, its eyes waggling around on stalks. My mum and we kids recoiled. Moments later, the whole platter returned: everything was split in half like a Damien Hirst sculpture and steaming! We refused to eat anything at all. It didn’t help that we were all sunburnt and tired. My dad was very angry.

My father will eat anything. It’s probably a reaction to war-time rationing. He’ll suck the bone marrow out of bones…not just from his plate, from yours too. He was intolerant of any fussiness at the table; we were pushed to eat frog’s legs and snails.

The snail incident was traumatic; we stayed in a farmhouse in France that belonged to family friends. The back room was dedicated to keeping snails, mostly kept in buckets; their digestive systems were ‘cleaned’ by being fed on bread for three days. Some of the snails escaped, they were everywhere, shiny trails on the chalky walls and stone floor. We went to a nearby restaurant that served snails stuffed with garlic, butter and parsley. My dad exhorted us to try.

‘Go on, just one.’

We three kids spent the next couple of days in bed with terrible diarrhoea. Our bedroom was upstairs in this farmhouse, thankfully far from the snail room, but there was no inside toilet. We spent two days shitting in a communal bucket as we were too ill to make it to the outside toilet. I never tried snails again.

On this same trip, same farmhouse, my dad woke us early.

‘We are going mushroom hunting,’ he whispered.

Sleepy-eyed, we stepped out into the dark and walked what seemed like forever, down the poplar-lined French country roads to the forest. On this holiday, my dad read us a chapter every night, with all the voices, from The Lord of the Rings, by the huge fireplace. The forest, when we arrived, seemed to me to be populated by elves, trolls and hobbits. After hours of searching, dawn came, and all we had found were three orange chanterelle mushrooms and a few ceps. We carried them back to the farmhouse, where they were fried in butter and garlic. Nothing has tasted better since, although we found the texture of the ceps a little slimy. I still love to forage for mushrooms in the autumn.

In London, special occasions were marked with dinner at Robert Carrier’s restaurant in Islington. I remember my first meal there: every course was tiny and perfectly arranged on the plate. Sights that are now common in haute cuisine, like French beans all lined up in a neat pile, exactly the same size, were objects of wonder back then. You felt you wouldn’t get enough to eat, but of course you did.

One night my dad brought home an entire octopus. He laid out this huge tentacled creature, with its large body full of ink, on the kitchen table. We kids came down to stare at this monster. My dad was excited; my mum left the room, muttering, ‘I’ll leave you to it.’

In those days Google didn’t exist. My mother’s cookbooks didn’t explain how to deal with octopus either. So my dad, a journalist, dealt with this crisis just as he would a story: call an expert, a good ‘source’, and ask them. He phoned Robert Carrier, whom he didn’t know and who was at that time probably the most famous chef in Britain, at his restaurant. In the middle of service. Robert Carrier, a very helpful gentleman, came to the phone and patiently explained to my father how to remove the ink sac, prepare and cook this octopus. He followed the instructions, amazed, despite his habitual cheek (something I seem to have inherited) at getting this help.

Of course, none of us would touch it.

My background is part Italian, part Irish and entrepreneurial to the core. My great-grandmother Nanny Savino had a shop in her Holloway council flat. I loved visiting her; the hallways were lined with bottles of Tizer and R. White’s lemonade, the bathtub with pickled pig’s trotters, the kitchen provided toffee apples and apple fritters and, most excitingly, under her enormous cast-iron bed were rustling brown boxes with the illicit earthy smell of tobacco – Woodbines, Player’s Weights cigarettes and matches. People would come to the door and ask to buy cheap fags from ‘Mary’. Her real name was Assunta but no-one could pronounce it. She came to Britain at the age of 16, before the First World War, from the small town of Minori, south of Naples. During the Second World War, the Italians were our enemies and her radio was confiscated. She wasn’t put in a camp, as several of her sons were in the British army. I never met my great-grandad, but from family stories he seems to have been a skinny man, under the iron fist of my enormous, rectangular, black-clad Nan. They started small businesses: a cart selling home-made ice-cream in the streets of Islington, then an Italian café. Even at the age of 80, infirm with arthritis, Nan was doing business from her house. It’s the Neapolitan way; even today there are independent street-sellers in Naples.

One of my most memorable meals was when I was eight years old, and we drove to Minori to see the Italian side of the family, many of whom lived in caves (the front looked like an apartment but the back was a rocky cave). My father’s godfather turned out to be the mayor of the village. He took us to a darkened restaurant, the best in the locality. The godfather wore a crisp white shirt, a tailored dark suit and gold glinted about his cuffs. The small finger on his right hand had a long, curly, yellowing nail. This was an Italian peasant’s way of saying ‘I don’t have to work the land.’ The waiters lined up as if it were a royal visit. Nobody kissed the godfather’s ring, but that wouldn’t have been out of place.

As we left, my brother piped up:

‘Dad, I like this restaurant, we don’t even have to pay!’

My parents hushed him. A few days later, we were invited to the godfather’s house. We had to climb a small mountain of lemon groves; the lemons were half a foot long, with thick knobbly skins, so sweet you could eat them straight off the plant. I remember being so thirsty as we made our way up the dusty lemon grove. The crickets were deafening and the sun beat down. At the top we were welcomed by the widowed godfather’s two 16-year-old daughters – twins I think – who had made us dinner. This time the godfather was wearing a white vest and blue work trousers. This dinner lasted for hours; they had pulled out all the stops: antipasti, pasta, a seafood course, a fish course, a red-meat course, a white-meat course, salads, vegetables, cheeses, puddings. It was the first time I had cannelloni, large stuffed rolls home-made by the young girls. It was a tremendous feat, this banquet, especially for such young cooks. We didn’t speak Italian (they spoke in dialect) and they didn’t speak English. After a few courses, we were struggling; my brother saved the day by groaning and clutching his stomach. At first the girls found this funny and offered him camomile tea but eventually his cries grew so loud and insistent that we had an excuse to leave.

Looking back, meals like this were the inspiration behind The Underground Restaurant, an attempt to recreate the languorous feasts of the continent. You see, the buzz for me, the shiver up my spine, the ‘Oh wow, this is all worth it’ moment, lies in these words: ‘community’, ‘sharing’, ‘experimentation’, ‘dismantling boundaries’. My instrument is food, that which binds us all (sounds a bit Lord of the Rings, doesn’t it?). We all need to eat. Many of us love to cook.

Feeding is how mothers show their love for their families. It’s how countries and communities and religions and families can identify with each other. Meals are memories, milestones in our lives; the first date, the lover that proposed, the husband that did not return for dinner (in retrospect, the first signs of divorce), the tentative feeding of your baby, the family discussions and rows around the table as the children grow up. Sunday lunch, one of the few remaining meals requiring mandatory attendance for family members, is where you might bring a prospective mate to meet the relatives. When I travel, new tastes and smells are intrinsic in recalling that country. Food divides us too: religions are distinguished via what they will not eat or drink.