Полная версия

The Mystery of the Cupboard

You couldn’t change your mind, could you?

Good luck with your new school and the Tea Cosy. Maybe she’s bald underneath it. You’ll have to try to make it fall off and see. My school’s a real toilet. See ya.

Patrick.

P.S. Em and Tamsin are still at the old school. Em told me Mr Johnson fell off his bicycle into some prickly bushes. She says he’s never been the same since the day of the storm. Keeps talking to himself, there’s a rumour he’s gone a bit irregular.

This letter at least took Omri’s mind off Kitsa for a while. After reading it, he went up to his room.

He’d chosen one of the ‘inner’ bedrooms so that he would be the one who had to pass through Gillon’s room to get to the stairs, and not the other way round. It was not a perfect arrangement, but better than Gillon having right-of-way through his room. He’d made Gillon - who had been desperate for the outside bedroom - promise always to knock, if he did need to come in, which was unlikely. Omri was a very private person. He planned to put a bolt on the door, like his old room had.

His new bed was up, and his new desk. They were both pinewood. He’d decided to put up loads of shelves, or rather ask his dad to. His dad, however, was overwhelmed with work.

“Time you learned to put up shelves for yourself,” he’d said shortly, on Day One.

“Okay! Can I borrow your drill?”

“No.”

“So how can I—”

“Oh, I’ll do it eventually! Give me a chance, I’m up to my neck!”

Meanwhile, Omri made do with some planks he found - that was one great thing about this place, there was so much junk lying about — laid across piles of bricks. He cleaned them all first and the shelves looked quite good. Since losing all his stuff in the storm he’d collected a few new books and some other bits and pieces, and these he arranged on the new shelves.

He looked at the top shelf and thought how good IT would look, standing right in the middle, with its new coat of white paint and new mirror in the door…

No. He mustn’t be tempted. He’d made up his mind. No more of that. He’d promised himself. He must stick to what he’d decided. He fingered a small neat parcel in his jeans pocket. Where to put it? Where would be a really safe place?

“Ah!” he exclaimed aloud.

He took four more bricks, and turned them so the indented sides faced each other. Then he opened the packet, put Little Bull and Twin Stars and the baby, and the pony, between two of the bricks, lying down in the little hollow, and on the other side, between the other two bricks, he laid Sergeant Fickits and Matron. He felt there was something faintly scandalous about them lying side by side like that, but after all, they were plastic. Wherever they were in their real lives, they wouldn’t know, and the main thing was for them to be safe from discovery. He laid another plank-shelf across the top.

Suddenly he stiffened, raising his head. He thought he heard— he rushed to the narrow window and leant out, calling. But no. It must have been another cat.

*

It took about three weeks to settle in. Omri and Gillon started school in the local comprehensive. They could get there in ten minutes on their bikes through the country lanes. It was a far cry from Gillon’s predicted ‘tinny country school with eight pupils’; it had over a thousand, and felt strange at first. Mrs Everest (whom Omri called Tea Cosy but the other kids called Peaky) turned out to be all right - strict, but okay. Nobody could get her wig to fall off, and rumour had it it was glued on. Omri’s form teacher was a middle-aged man called John Butcher. Obviously he didn’t need a nickname.

Adiel set off for boarding school, a big one outside Bristol. He had all his things in a trunk, rather like Omri’s old chest only made of metal. They wouldn’t see him again till half-term. Omri missed him and didn’t miss him. Even when he missed him, he didn’t miss him half as much as he missed Kitsa.

He was sure now she would never come back. He tried to resign himself, to think of her being free, enjoying the naturalness of her new life, but the trouble was, she wasn’t used to the country and when he let himself think about it, he didn’t see how she would manage. She’d never hunted in her life, beyond a halfhearted pounce at the odd bird - and the time she’d nearly killed Boone, of course, but that was just a fluke.

And there was worse. They hadn’t been there a week before a fox got into the henhouse and killed three of their hens. If it could do that, it could surely kill a little town cat. Thoughts of her nagged him like an aching tooth he kept biting on to see if it still hurt.

One evening at supper — meals were only just stopping being picnics — Omri’s father said, “Oh, by the way, Omri. I was talking to the bank manager today. Your mysterious package has arrived at the local branch and is in the safe.”

Gillon looked up. He hadn’t heard anything about the package till now. “What’s this?” he asked.

“Nothing,” said Omri quickly, and signalled his father, who caught on at once and refused to say any more.

Gillon, however, wouldn’t leave it alone.

“What package? What was Dad talking about?”

“Oh, mind your own business!” Omri yelled at last.

That was it for the moment, but the next day at school, Gillon found Omri in the playground and said cockily, “I know what your mystery package is.”

“You do not.”

“I do. It’s your cupboard, isn’t it?”

Omri felt the blood rush to his head. He gaped at Gillon.

“Your face! Did you think I didn’t know?”

“Know… what?” Omri half gasped.

“That you’re hooked on it. But putting it in the bank? Pretending it’s valuable? Get real. The bank’s only for really valuable things, like jewellery or gold.”

Omri bit his tongue and said nothing. He kicked the turf and stared at the toe of his trainer.

“If I told Dad what it was—”

“Tell him if you like.”

“If I told him, he’d go straight away and get it out. It’s using up space. The bank safe isn’t for toys.”

“You gave it to me. You should be pleased I like it.”

“Yeah, but — the bank — it’s just stupid.” They stood for a moment, staring out across the acres of green, so huge, so different from the hemmed-in tarmac playground in town. “There’s nothing special about it. Is there?”

“It’s special to me. It was smashed up in the storm, and I mended it. I don’t want anything else to happen to it.

“And did you put the key with it?”

Now Omri visibly jumped. “What key?”

“The one you locked the cupboard with when you were playing with it. The one with the red ribbon that Mum used to wear on a chain.”

Omri felt winded. He couldn’t think what to say, and every second he didn’t turn it all off with some careless remark made it more obvious to Gillon that he’d stumbled on a really important secret. He was staring at Omri now with an ever more beady look of interest and excitement.

“I know there’s more to that cupboard than you’re telling,” he said at last. “I’m sorry I laughed about the bank. Maybe it really is valuable. I wish you’d tell me.”

There was a long silence. Then Omri suddenly shouted, “Well, I’m not going to!”

Turning, he ran fast towards the hedge at the far side of the playground. It was about a hundred yards away. When he got there, panting, he sat down on the grass in a hidden place. Gillon hadn’t followed him.

Omri put his head on his knees. He was shaking. Something terrible had almost happened. He’d had a strong urge to tell Gillon. He had wanted to tell him. Gillon of all people, who made fun of him, who could never in a million years keep such a secret to himself. What had come over him? Why had he had to run away fast to stop himself from blurting it out?

He didn’t understand this feeling. It felt more like loneliness than anything else. People did really crazy things when they were lonely. But how could he be? He had his family, he was making new friends at school… Of course he missed Patrick… and Emma… and what he thought about as ‘the old world’. But that wasn’t it.

It couldn’t be old Kits, could it? You couldn’t miss a cat so badly that it made you weak and apt to do stupid things, blurt out a vital secret just to share it with someone?

He’d have to watch himself.

He heard the bell in the distance. He got up slowly and walked back to the school, saying over and over again, “Never. Never. Never. Never must I tell.”

3

Hidden in the Thatch

Omri’s father lost little time in getting the re-thatching of the roof underway.

He had been making enquiries among neighbours and people in their local village and pretty soon some men arrived in a beaten-up old car to inspect and measure the roof and talk money. A very great deal of it. That evening Omri saw his mother carrying a large tumbler of brown liquid across the lane to the big workshop his father had adopted as a painting studio.

“Is that whisky, Mum?” asked Omri with interest. (The cowboy, Boone, had been a great whisky drinker, but his father wasn’t.)

“Yes,” said his mother somewhat grimly. “Your father has had a shock. Alcohol was invented for times like this.”

“How much of a shock?”

“Fifteen thousand pounds’ worth,” she replied.

“Blimey! Just for a bit of straw?”

“Just for a bit of straw.”

But it wasn’t only for that, of course. Thatching was a skilled craft, and not many people still knew how to do it properly. And it wasn’t straw. It was reeds, and the right sort only came from a particular place in France, because in Britain the reed beds were protected and couldn’t be used. The work would take about four weeks. And they had to do it at once because it couldn’t be done in winter - the whole of the old roof had to come off.

“Like when the storm blew our other roof off!” said Omri the next day at tea when all this was being gone into.

“Dad, it’s going to be so cold!” said Gillon.

But their father said tersely, “We’ll all have to be terribly brave about that, won’t we, Gillon?”

“Lucky old Ad, safe and snug at school,” muttered Gillon, who certainly hadn’t shown any envy for his older brother so far.

“Look out of the window, boys,” said their mother suddenly. “We’ve got visitors.”

They went to the window. On the lawn were three large magpies, gleaming black and white in the sun, strutting about and pecking at something that lay in the long grass.

Omri had a moment of absolute horror. He knew magpies were scavenger birds — he’d seen them pecking at the remains of one of the fox-killed hens. What could be lying there, dead?

He rushed out of the house, his heart in his throat. The birds flapped unconcernedly away just as he reached them. Hardly able to bear his apprehension, Omri parted the grass and looked at the corpse.

It was a half-grown rabbit without a head.

The others, belatedly realizing what Omri had feared, trailed out after him.

“It’s not her, is it?” called his mother.

“It’s a dead rabbit,” said Omri.

“Yuck,” said Gillon. “Those magpies have eaten half of it.”

Their father bent down to look at it more closely.

“I don’t think the magpies killed it,” he said. “Too big for them. It would take a fox to kill that, and why would he have left it half eaten? Looks more like a cat’s work to me.”

Omri gazed at the dead half-rabbit with entirely new eyes.

“You mean - a cat could kill a thing that size? You mean maybe Kitsa could have hunted it?”

“It’s possible,” he said.

Omri’s heart did an upward lurch. The hope he had abandoned rushed back, painfully, like the blood coming back into a numbed limb.

“But if she’s around, why doesn’t she come home?”

“Maybe she’s gone feral,” said his father.

“Gone feral? What’s that?”

“Wild. Cats do. Mainly tomcats, but queens do as well sometimes, when they’re moved. I bet she’s around, Omri. Keep your eyes open for her, and keep putting out her milk.”

Omri put not milk but clotted cream out for her that night. In the morning it was gone.

“Probably a hedgehog,” said Gillon.

Omri wanted to hit him, but he felt too relieved. There was hope, after all.

The thatchers arrived to begin work, and chaos came again to the just-organized-after-moving household.

The garden, the hedge, the border of the lane, and all the paths vanished under masses of mouldy old thatch as the thatching team tore it off the roof beams. There was no point in clearing most of it till the job was done, but Omri was told to keep the route from the lane gate to the front of the house cleared. He did this after school. Every day for the first week it had to be done again. It was absolutely amazing how much old thatch there was - enough to make three or four haystacks. It kept piling up all around the house.

The thatchers expected regular cups of tea, and when the weather turned really hot at the end of September, relays of beer. They got chatty. In breaks, they sat out on the thatch-littered lawn and discussed their craft with anyone in the family who would join them.

One afternoon after school, Omri was drifting past and heard one of them say, “We ent found that oul’ bottle yet. Last chaps hid it thorough, seemingly.”

He paused. “What old bottle?”

The men grinned. “Don’ ee know about the thatchers’ bottle?”

“No?”

“We were tellin’ your dad. Right int’rested, he be. Wants to see un when we find un.”

“But what is it?”

“It’s like this here, see. Every time a roof gets thatched, which is about every thirty year, the thatchers all writes their names on a paper—”

“On’y in the olden days they’m put a cross instead—”

“And any details as is relevant to the job, and puts it in a bottle, along with the papers from the thatchers as done the last job, and the one afore that. And they hides it in the thatch, for the next ones to find, thirty year on.”

“That way,” put in another, “there’s a link, see, from one generation of thatchers to the next, down the line, maybe ‘undreds a years. This ’ouse now, it’s been standin’ not far short o’ three ’undred year, wouldn’t ee say, John?”

“Since 1704,” said Omri eagerly. “The plaque says.”

“Arh, the plaque, well, there you are then. Musta bin - let’s see - between seven and nine thatchin’s in that time, maybe more, so it’ll be a ruddy big oul’ bottle, I reckon, when we do find un.” They all laughed and drank down their lager.

Omri was intrigued about the bottle, and so was his father.

“A real link with the past,” he kept saying. “If they find it I’m going to make photocopies of all the papers, to keep, before they add their one and hide the bottle again.”

“Can we keep the old bottle, Dad?”

“No. They use the same one till it gets broken. That’s the custom. I love old country customs. I respect them. A real link with the past!”

“Yeah, Dad, you said that,” said Gillon, who found the whole thing a total turn-off.

That night Omri lay awake in his new room, under the denuded roof and bare eaves, with the window open.

The milk dish had been empty again this morning, and he’d wanted to keep watch all night, but of course his mother wouldn’t let him. It was hard to fall asleep anyway. He was so used to traffic going past all night, and London streetlamps lighting the room, he still wasn’t quite used to the darkness and quiet of the country.

Not that it was dark tonight. There was a full moon. It bathed the surrounding hills, fields, and woods, and shone down through a little tear in the roofers’ tarpaulin over his head. It was a bit like his old room where he’d slept on a platform under a skylight. It had felt like sleeping out under the sky.

Suddenly he sat up. He’d heard a cry. It sounded just like the cry of a cat in distress!

Without thinking, he jumped up and rushed through Gillon’s room (which he had to pass through to get to the stairs), and fumbled his way down and out into the soft-scented, unfamiliar, mildly scary country night, full of rustlings and creature noises that you never heard in London.

In bare feet and by the clear light of the moon, he kicked through the fallen thatch, crossed the sloping lawn, let himself out through a little picket gate, and started pushing through the overgrown grass in the paddock, calling softly, “Kitsa! Kitsa, come on, Kits!” and making shwsh-a-wisha noises that used to bring her running. His feet were stung with stinging nettles and pricked with thistles, but he kept going until he stepped in an old cowpat - that was too much!

“Bloody country!” he exploded, and turned back, but not before he’d had a long listen. He couldn’t hear her now. It must have been a bird or something. He scraped his foot on the damp grass to clean it. Then he picked his way back towards the front door.

It occurred to him, just as he was about to go in, to have a look to see if the milk had been drunk yet. Instead of walking in the front door and out again at the back, because of his mucky foot he decided to walk round the outside to the kitchen door, which he did, treading on layers of old thatch all the way. And while he was passing under the plaque on the gable end, he nearly twisted his ankle stepping on something lumpy and hard.

It didn’t feel like a stone, so he fumbled about in the thatch to see what it was — maybe it was ‘the oul’ bottle’! It would be fun if he could be the one to find it, not the thatchers at all!

The rotted reeds had all matted together and must have fallen off the roof in a clump, instead of in thousands of loose bits like most of it. It felt disgusting to his groping fingers, and the smell of mustiness and rot — which pervaded the whole house — was very strong. Yet in the middle of it was undoubtedly something solid.

He fished it out. It wasn’t a bottle, old or otherwise. It was an oblong package wrapped in blackened, disintegrating cloth and tied with thick string that came apart at his first tentative tug.

He dropped the string on the path and moved back to the front of the house, into full moonlight. The bit of cloth was thick and heavy, like canvas. Omri carefully unwrapped it. His heart was beating very hard for some reason. He was suddenly terribly excited. What could this possibly be, that someone had hidden in the thatch perhaps as much as thirty years ago?

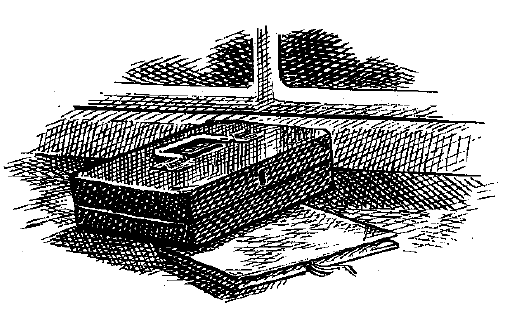

Inside the wrapping was a small black metal cashbox with a curved brass handle. It had a slot in the top to put coins in, but this was sealed with some lumpy hard stuff. It was very firmly locked. Separate from it was another, flat package that had lain under the box inside the cloth.

When Omri unfolded this second piece of canvas, he found a thick notebook inside. It had a leather cover with metal corners, and it was full of writing.

Unluckily, Gillon woke up as Omri was creeping through his room to get back to his own, and got a fright.

“Who’s there! Who’s there!” he yelled right out loud. Next minute their father had come crashing through Omri’s room from the parents’ room beyond that.

He switched on the light and Omri stood revealed. He thrust his find up his pyjama jacket and in the sudden blaze of light on everyone’s sleepy eyes, nobody saw him do it.

“Omri! What do you think you’re doing at this hour?”

“I — I thought I heard Kitsa crying.”

“Blasted cat! She’s all right! Go to bed.”

“I’m just going. Sorry. Sorry, Gilly.”

Gillon, still half asleep, mumbled something and rolled over. The light went out and Omri followed his father into his own room. His father then went through the other side into his bedroom. Omri shut both doors. Privacy — there wasn’t any. He was going to have to do something about this.

Trembling with excitement, he lay down on the bed and waited till everything was quiet. The pattern of moonlight had altered as the moon began to set. He got up and sat in its beam and set the cashbox on the floor. He opened the notebook.

On the first page were a few words in the most beautiful delicate handwriting. He could just about read them, although the ink had faded to a pale brown.

Account of My Life, and of a Wonder Unacceptable to the Rational Mind. To be hidden until a time when Minds in my Family may be more Open.

There was a name. A three-word name. In the wan light of the setting moon Omri could hardly read it till he carried the notebook to the window.

The name was Jessica Charlotte Driscoll. And there was a date. August 21st, 1950.

August the twenty-first! Another sign — another coincidence, like the LB on the plaque! August 21st was Omri’s birthday.

Jessica Charlotte Driscoll.

The name Driscoll meant nothing to Omri. Nor did Jessica. But Charlotte! Charlotte was the name that Lottie was short for. And Lottie had been Omri’s mother’s mother’s name.

But the moment the thought crossed his mind that this could be that Charlotte - his grandmother - he banished it instantly. That was impossible. His grandmother had died in the bombing of London in World War Two, when his own mother was only a few months old. By 1950 she would have been dead for eight years.

Anyway, even though this house had been owned by some distant cousin, any connection between it and his grandmother was impossible. She had lived in south London all her short life. His mother had told Omri that the only place his grandmother’d ever visited out of London was Frinton, a seaside place where her sailor husband had taken her on their honeymoon.

No, all right. So this Charlotte wasn’t a relative.

Or was she? She must have been living here before the elderly cousin who had recently died. If she’d been a relative of his, she might also be a relative of Omri’s.

Omri dared not switch the light on and start to read the notebook because there weren’t curtains yet, and his parents would be sure to see the light through their window. He had to compose his soul in patience till the morning. He slept uneasily with the notebook under his pillow and the cashbox - the cashbox! what could be in there? - hidden under the bed.

A Wonder Unacceptable to the Rational Mind…

Omri knew a bit about that. ‘There’s real magic in this world…’ Even Patrick knew it now. Patrick the practical, the doubter, the one who’d once tried to pretend none of it had happened. They’d had proof enough to convince anyone. A little bathroom cabinet that, when you locked it with a special key, became a magic box that brought plastic toy figures to life. And more than that — they were not just ‘living dolls’, but real people, magicked from their lives in the past.

Little Bull had been the first, and, for Omri, would always be the most special - an Iroquois Indian from the late eighteenth century, coming from a village in what was now the state of New York. Then had come others: Tommy, the soldier-medic, who’d later been killed; Boone the cowboy (he was really Patrick’s special pal), and Twin Stars, Little Bull’s wife, and her baby who had been born while she was with them. Matron, the strict but staunch nurse from a London hospital of the 1940s. And Corporal - now Sergeant - Fickits, the Royal Marine who had helped them defeat the skinhead gang who had broken into Omri’s old house…

They were so real! So much a part of Omri’s life… It was hard to keep his vow to do without them, to eschew the magic. But he must. Because it could be dangerous. The storm that had wrecked half of England had been brought by them, with the key. People had been killed… in the present, and in the past. It was frightening. It was too much to handle.