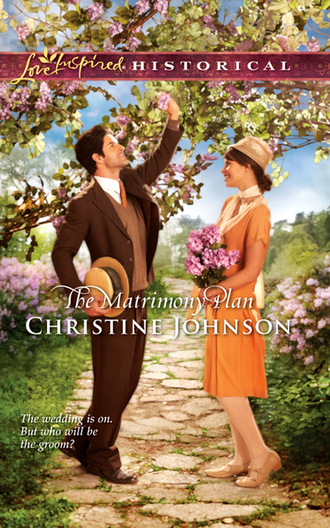

The Matrimony Plan

“But shouldn’t we begin soon?” Beatrice asked. “I understand it can take some time for a window to be constructed. Bad weather will be here before we realize it.”

A lady always maintains her composure. Felicity kept her head high. “Everything is under control.” It clearly was not.

Gabriel was upset with Mother’s project, and Robert had resumed talking about the airfield. If she didn’t do something quickly, she’d lose her chance to claim his attention.

“I’m terribly hot,” she exclaimed, setting her napkin on the table. “May I be excused, Daddy? I’d like to take some air.” She didn’t wait for his approval to push her chair back.

“May I escort you, Ms. Kensington?” Robert asked, setting aside his napkin. He held out a hand.

Perfect. She beamed as she placed her hand on his. At last, her plan was underway.

Gabriel itched to follow Felicity, but she could never care for a man who chased after her. So he waited anxiously for the meal to end.

The Wellington lost its flavor, and he couldn’t ignore the empty places beside him. What would they say to each other? What would they do? No small part of him wanted to run out and protect her, for what kind of man spoke so carelessly of passion, equating it with lasting love? He knew the answer: a man who wanted to use a woman for his own pleasure.

“It is hot in here,” Kensington said, interrupting Gabriel’s thoughts. “Let’s all take our dessert in the garden.”

Though Gabriel eagerly assented, judging by the grim set of Eugenia Kensington’s lips, she supported her daughter’s withdrawal with Blevins. Thankfully her father had better sense.

They caught up with the pair on the porch. A waning moon couldn’t compete with the bright gas lanterns lining the driveway. Moths fluttered against the globes, hopelessly attracted to what would kill them.

Felicity still hung on Blevins’s arm, gazing into his ridiculous face with adoration.

Peeved, Gabriel asked if she felt cooler now.

Felicity ignored his question. “Founder’s Day,” she whispered to Blevins. “Remember, green satin ribbon.”

Judging by Blevins’s grin, he understood what she meant, but instead of answering, he kissed her hand and broke away just as Kensington approached.

“Mr. Blevins, join Blake and me in the study,” the patriarch said. “I have a question about your blueprints.”

Blevins of course obeyed. He had little choice, since Kensington employed him, but that left Gabriel to reap the rewards of being alone with the ladies. He snared a crystal bowl of strawberries with cream and offered it to Felicity.

“Would you care for dessert?”

She hugged her arms and shivered. “No, thank you. I’m still a bit fatigued.” Without asking his pardon, she departed, leaving a faint scent of roses lingering in the air.

Gabriel knew a brush-off when he saw one. Felicity Kensington not only preferred Blevins but she disliked him intensely. The feelings he had for her were not mutual.

He gathered the remnants of his battered pride and faced the remaining women. Eugenia and Beatrice Kensington had watched the entire exchange. Felicity’s mother smirked, while Beatrice looked dismayed. Gabriel forced a smile. “Nice evening.”

They exchanged small talk, but he could barely keep his mind on the conversation. He wondered what Felicity meant by those furtive instructions to Blevins. Clearly they’d planned to do something on Founder’s Day, whenever that was, but what did the green satin ribbon mean? Was it to indicate where they could meet in secret? Surely there was no need. Eugenia Kensington clearly supported a match between her daughter and Blevins. Clandestine meetings always led to no good. Gabriel had seen his share of unwed mothers, abandoned by their lovers as soon as they were with child. He shuddered to think that might happen to Felicity, but he didn’t trust Blevins. Something wasn’t right about the man.

“Pastor, glad to see you’re still here.” The hearty greeting came from Branford Kensington, flanked by his son and Blevins. He shook Blevins’s hand. “Shall we call it a night? You’ll want to start first thing in the morning.”

Blevins apparently understood a dismissal when he heard one, for he gathered his hat and cane and thanked Mrs. Kensington for a fine dinner. As the man passed, Gabriel smelled whiskey. That shouldn’t be—not with prohibition. Yet somehow he’d gotten liquor.

Kensington’s intense gaze honed in on Gabriel. “You and I have a little unfinished business, Pastor. Let’s go to my study.”

That was not a suggestion; it was a command. Gabriel swallowed a nut of worry. What had he done to upset Kensington? Had he been too forward with Felicity? Did Kensington suspect his interest in her? Every step down the long hall intensified his dread.

The study was paneled in mahogany and filled with heavy furniture. A gun rack with nine hunting rifles spanned the wall behind him. A Cape buffalo head stared blankly with dark, glassy eyes while gazelle, moose and antelope mounts graced the other walls.

Rather than sit in the low chair across the massive desk from Kensington, Gabriel remained standing. He’d been forced low enough for one night.

“Care for a drink?” Kensington pulled the stopper off a crystal decanter filled with a dark liquid.

Whiskey. Fingers of dread danced along Gabriel’s spine. That’s where Blevins got it. Kensington might have stockpiled a legal supply before the law took effect. Even if he hadn’t, like most rich men he would think he was above the law.

“I don’t drink,” he said with quiet condemnation.

Kensington held the stopper in midair and laughed. “It’s sarsaparilla, son, not alcohol.”

But Gabriel had smelled whiskey on Blevins. Perhaps Blevins carried a flask, or maybe Kensington put the liquor away for the minister.

“I’m not thirsty.”

“Suit yourself.” The man rapped his knuckles on the desktop before taking his seat. “I’m a man who likes to get straight to business.” He leaned back in his chair, at ease with the world and whatever he had to tell Gabriel. “You’ve seen the town, inspected the church, met a good portion of our congregation. You’re a man of education, correct?”

Gabriel nodded, though the question was rhetorical.

“Then you see how things add up around here.”

Gabriel saw nothing of the sort. “What adds up?”

Kensington smiled paternally. “You’re a bright young man and can see how things run in this town.” He steepled his fingers. “There’s one thing I’d like you to keep in mind.”

Gabriel’s mind raced through the hundred things Kensington could demand: silence about illicit alcohol, blinders for every indiscretion. He could even dictate the sermon topics.

Kensington leaned forward, gaze intent. “Remember who’s in charge.”

“What?” Gabriel backed up, not believing what he’d just heard. The man was threatening him, telling him that he had to get approval for every idea.

“I think you know what I mean.”

The initial shock settled in Gabriel’s belly with a dull fire that grew with each successive thought. He had ignored every slight and innuendo tonight. He’d endured Eugenia Kensington’s derogatory comments and turned a cheek to Blevins’s superior attitude, but he could not accept bullying.

Nor could he remain silent when the evil of drink was seeping into this town. Gabriel Meeks did not bow to any man.

“Yes, I do, sir.” He trembled beneath shackled ire, ready to fight. “I know exactly who’s in charge. God is.”

Gabriel spun away but not before glimpsing a peculiar grin on Kensington’s face. The man thought he had Gabriel exactly where he wanted him. Well, he was wrong.

Without a word, Gabriel left the room, the house and very likely his first pastorate.

Chapter Four

Day two, and Felicity’s plan was progressing on schedule. Even though Robert hadn’t asked to see her again, he would have if the rest of the dinner party hadn’t shown up at the most inopportune time. Still, she’d won his assurance that he would bid on her Founder’s Day picnic basket. A little trinket inside would assure him of her interest.

That’s why she deliberated over the small collection of luxury goods in the mercantile’s display case. The morning sun streamed through the store window, sending a thousand sparkles off the paste jewelry. She drew her attention to those items suitable for a man of recent acquaintance. Sterling hat brush, watch or pocketknife. None of them struck her as perfect. She wondered if Blake had any stock not yet on the shelves.

“No, Ms. Kensington,” Josh Billingsley said in answer to her query.

“Any due in over the next week?”

“I wouldn’t know.”

He didn’t even look at the order book. Honestly, her brother should hire better help. She examined her options again. Perhaps a book. The slender volume of Wordsworth had a calfskin cover and ribbon place marker, but would Robert read poetry? Gabriel yes, but Robert? She imagined Robert reclining at the picnic, reading love poems to her. Though she could picture his strawberry-blond hair and outrageous mustache, the voice was always Gabriel’s rich baritone.

Definitely not Wordsworth. Perhaps the hat brush? Too impersonal. The pocketknife? Too masculine. Besides, he’d already have one.

She bit her lip, trying to decide, and overheard a pair of giggling voices—Sally Neidecker and Eloise Grattan, if she wasn’t mistaken. The two stood directly behind her, hidden by the tall candy display. They’d been inseparable since the first day of primary school. Whiplike Sally, whose parents’ wealth was second only to Felicity’s, stuck her nose into everyone else’s business while Eloise blundered along blindly with everything Sally suggested.

“He looked at me,” Eloise giggled. “Did you see it?”

“Who didn’t?” Sally whispered. “He likes you. I can tell.”

Felicity could guess whom they were talking about. Gabriel. Good. She needed to wipe him from her mind. The image of Gabriel kissing Eloise Grattan was just the thing. She picked up the book of Wordsworth and leafed through it.

“Do you really think so? I’m not too young?” Eloise’s voice fluttered with nervous worry.

Too young? He couldn’t be more than a year or two older than her. She stifled a laugh, and the book accidentally knocked the glass of the display case.

“Shh,” Sally said. “Someone’s listening.”

“Who?” asked a panicked Eloise.

Felicity buried her head in the book and pressed into the corner, out of their line of sight.

“It’s only Felicity Kensington,” Sally said after a moment, “and she’s busy reading, but just to be safe, pretend you’re looking at the candy.”

“But I am looking at the candy.”

“To buy some, silly.”

“I was going to get some horehound drops,” Eloise said, and for a moment Felicity felt sorry for her. Sally was sure to ridicule the choice.

“Horehound? That’s for sore throats.”

“Pa likes them,” Eloise said weakly.

After that, the conversation stopped for so long that Felicity thought they’d left. She edged out of the corner and spied the two girls still at the candy counter.

“You don’t think I’m too young?” Eloise asked again.

“Not at all,” Sally said flippantly. “Some men like younger women.”

Felicity rolled her eyes.

“But my size—”

“My brother says men like a woman with some meat.”

Joe Neidecker might like substantial women, but Felicity doubted Gabriel did.

“Do you think I have a chance?” Eloise whispered.

Sally’s voice lowered, but Felicity could just make out the last bit. “…the barn after lunch.”

They were going to the barn? Felicity nearly dropped the book. Eloise wasn’t infatuated with Gabriel. She wanted Robert. Impossible. He would never fall in love with someone like Eloise. She had no breeding or wealth. She brought nothing to a marriage.

“Don’t worry. I’ll be with you every step of the way,” Sally said.

Felicity’s pulse beat faster. Sally didn’t offer her assistance unless she expected to gain something, even from her sidekick. Eloise might think Sally was joining her to help, but in the end, Sally, not Eloise, would have Robert—unless Felicity got there first.

She snapped the book shut. She couldn’t wait for the Founder’s Day picnic. If she wanted to secure Robert, she had to act now. But how? She couldn’t pester him like Eloise. That was sure to drive the man away. No, she needed a good, logical reason to interrupt his business or he’d only be annoyed. Business. That was it. She set the book back on the shelf.

“Oh, Felicity,” said Sally, sliding past her, “I didn’t see you. When is the committee meeting?”

“I’ll contact you,” Felicity said sweetly, as if she hadn’t overheard a thing. “I’m glad you’re helping.”

“Oh, not me. Eloise is on the committee. I’m far too busy to be on some silly old committee.”

“It’s hardly silly.” Felicity couldn’t believe she was defending Mother’s pet project. “The new window is important to the church.”

Sally shrugged. “Everyone knows the only person who really wants it is your mother. That’s why she named you chairwoman.”

Felicity clenched her fists. “No one supports this community more. Why, if it weren’t for the Kensingtons—”

“Kensington,” Sally snorted and rolled her eyes at Eloise, who giggled. “I wouldn’t throw that name around so much if I were you.”

“What do you mean?” Felicity demanded.

Again, Sally laughed. “Not a thing.” She took Eloise by the arm, and the two girls walked off, whispering to each other.

Felicity stood dumbfounded before the candy display. People disparaged the Kensington name on occasion, but no one had ever done so to her face.

“Kin I help you, Ms. Kensington?” Josh Billingsley asked.

She shook her head. Sally and Eloise’s snide comments didn’t matter. They were just trying to distract her from Robert. Well, they would not succeed. Felicity had one option they didn’t. As committee chairwoman, she could request Robert Blevins’s assistance with the new stained glass window. A man liked nothing better than to demonstrate his skill, and it would give her all the time with him that she needed.

Gabriel awoke the next morning with a sense of purpose and a stomachache. The former would propel his new sermon for Sunday, assuming he wasn’t fired before then. The latter undoubtedly sprang from that meeting last night.

After stewing about Kensington’s threat for almost an hour, he’d paid the exorbitant cost to place a long distance telephone call home. Dad could tell him what to do. Unfortunately, Mom and Dad were at the opera, and he could only talk with his sister, Mariah.

Though she usually made sense of the worst muddles, last night she’d offered no solution.

“Do what you must, Gabe,” she’d said over the crackling line. “And pray first.”

Prayer hadn’t brought sleep or a calm stomach, so first thing in the morning he headed to the drugstore for medicine. Before he’d walked a block, the one Ladies’ Aid Society member who hadn’t asked for a favor stopped him. Short and plump, Mrs. Simmons epitomized the loving mother. Her round cheeks glowed, and her blue eyes twinkled merrily.

“Pastor Meeks. How good to see you.”

Gabriel greeted her and smiled at her gawky teenage daughter, who hung back holding a basket covered in cheap gingham. He wished he could remember the girl’s name.

“Anna and I were just on our way to the parsonage with some cinnamon rolls.”

Anna. That was it. The delicious aroma of fresh bread and cinnamon revived his downtrodden spirit. “For me?”

Mrs. Simmons smiled broadly, her rosy cheeks round as apples. “You’re looking mighty thin.” She clucked her tongue softly. “No housekeeper or wife to keep meat on those bones. If you’re hiring, my Anna’s a hard worker.”

The girl kept her face averted, but Gabriel saw her blush.

“I’ll keep that in mind,” he said, “after my sister visits.”

If he wasn’t fired first.

“Oh my, you have a sister. Is she younger than you?”

Mrs. Simmons had such a kindly manner that Gabriel easily confided in her. After a few minutes talking about his older sister, Gabriel saw Blake Kensington drive by. Though the son had proven companionable, any Kensington reminded him that his fate still hung in the balance. The bile rose in his throat.

“Please excuse me.” He hated cutting off a parishioner, but he couldn’t concentrate on what she was saying when his gut hurt. “Can you tell me where I might buy something for a stomachache?”

“Mercy me, here I am prattling away when you need medicine. The drugstore’s across the street at the end of this block. You hurry on now, and I’ll leave the rolls on your porch.”

Though Gabriel insisted he could carry them, she would have none of it. “I’ll send Anna.” And before he could protest further, the girl sped off.

Mrs. Simmons then motioned him close and whispered, “Be sure to use the front entrance.”

“Why wouldn’t I?” he asked, puzzled, but she only bid him goodbye and headed for the post office.

What an odd thing to say. Customers never used the back door of a business. That was for deliveries and employees. He stopped outside the drugstore and examined the storefront. It looked like any drugstore with advertisements for tonic and perfume and lotions in the front windows. The interior was lined to the ceiling with narrow shelves and bottles. A long wooden counter, manned by an attractive, dark-haired woman of perhaps forty, kept customers from the strongest drugs.

He stepped to the counter. “I’d like something for stomach upset.”

The woman smiled pleasantly between the curled ends of her bobbed hair. “You’re the new minister in town, aren’t you?”

“Yes, I am. Reverend Meeks.”

“I’m Mrs. Lawrence. Would you prefer dyspepsia tablets or bicarbonate of soda?”

“The tablets, please, a half dozen.” If he didn’t butt heads with Kensington too often, he wouldn’t need more.

She slid the tablets into a tiny paper envelope. “That will be twenty cents.”

As he handed over the dimes, he heard two young ladies whisper behind gloved hands. He recognized them from the Ladies’ Aid Society meeting. One had been pushed by her mother to meet him, if he recalled correctly. Unfortunately, he couldn’t remember their names, a poor start for their pastor.

“May I help you, Eloise?” Mrs. Lawrence asked pointedly.

Eloise Grattan. That was it. And the one with the pointed nose must be Sally something-or-other.

“No, not today,” Ms. Grattan giggled, darting a glance his way.

Her mother had brazenly offered her daughter as a potential wife. Though Gabriel had come to town hoping to find a bride, he didn’t want one thrust on him.

“Ladies.” He nodded, eliciting yet another round of giggles.

The bell above the door tinkled when he left, replacing his irritation with a warm homey feeling. This was small-town America, the rural ideal he’d envisioned—girls giggled, boys played, clean air, bright storefronts and friendly townspeople—well, at least for the most part.

He waited at the corner for a motorcar to pass. The Packard approached quickly, and the driver blew the horn to warn everyone to scatter. For a second, the significance didn’t hit Gabriel. Then he remembered. This was Kensington’s car. Gabriel watched it turn into the alley behind the drugstore. What had Mrs. Simmons said? To be certain to use the front door?

Curious, he hurried down the street and reached the alley just as the motorcar was driving away. The heel of a man’s shoe vanished into the drugstore’s back door—Kensington, no doubt. Gabriel strode down the alley and tried the door. Locked. Whatever was going on, it wasn’t good.

Evil hides from the light.

What this town needed was someone to shine a bright light into the dark corners. They needed their eyes opened to the corruption around them. The people of this town needed a leader who would stand up to Kensington, not another puppet giving bland sermons and lukewarm advice. This town needed its spiritual and social fire relit. God had called him, Gabriel Meeks, to Pearlman for a reason. He now knew what that reason was.

Reinvigorated, Gabriel strode past the church to the park.

This whole business began in the woods behind the parsonage. Criminals, Coughlin had said. Gabriel now knew what the man meant. Something was going on near that broken-down fence, and he intended to find out what.

The route to Baker’s Field took Felicity past the park and the parsonage with its hedge of furiously blooming bridal’s veil. If she could get to the barn first, she could ask for Robert’s assistance before Sally and Eloise claimed his time.

She hurried past the cramped fields of Einer Coughlin, the last farmhouse before Baker’s Field. Though she couldn’t spot Robert in the field, a motorcar was parked near the barn. It looked like Blake’s, meaning Robert had to be there.

If she cut across Coughlin’s hayfield, she’d save precious minutes, but the man was the meanest farmer in town. Everyone blamed it on his wife’s untimely death and son’s running away, but Felicity sympathized with the wife and son. He’d likely driven them to their rash actions. Shiftless and stingy, Mr. Coughlin grew hay on the richest farmland in the township.

She hated walking by Coughlin’s land. Sometimes he’d yell at passersby. Occasionally he’d threaten them. She hurried past the ramshackle house surrounded by garbage and broken equipment. It was an eyesore and a disgrace and so close to the parsonage, too. Poor Gabriel.

Poor Gabriel? What was she thinking? She had set her cap on Robert Blevins, not Gabriel Meeks.

With a shudder, she scurried by the Coughlin place, head down. Just a few yards more, she thought. Then a pitiful whining made her stop. That came from a dog, and judging by its plaintive cry, it was hurt. Was the animal caught in one of the rusting buggies or plows near the house? If so, Coughlin would shoot it out of spite.

A horrible yelp set her in motion. She had to save the poor thing before it was too late, but where was it? At first, the cries seemed to come from near the house, but as she went farther into the newly reaped field, she realized the animal was behind the house, toward the river.

When she rounded the decaying wagon, she saw. Mr. Coughlin, rifle slung over his shoulder, dragging poor Slinky toward the river on a rope.

“Stop,” she cried, racing toward them.

The dog struggled against the rope with all his might, but Mr. Coughlin didn’t let go. With a jerk, the knot tightened around Slinky’s neck.

“Stop. You’ll strangle him.”

Coughlin kept walking.

The wet earth sucked the ivory satin pumps off her feet. She yanked the shoes out of the mud and tried again, but two steps later, the shoes came off again. It was no use. She grabbed the shoes and ran in her stocking feet. The hay stubble stabbed her soles, but she had to save Slinky.

“Stop. Stop.” She waved the shoes, but Coughlin didn’t hear her.

He steamed onward, slowed only by Slinky’s desperate resistance. The black-and-white dog snapped and nipped at the rope, but Coughlin yanked harder.

“Stop that,” she cried. “You’re hurting him.” She threw a shoe past the man’s head.

That stopped him. He squinted in her direction while Slinky tried desperately to rub the rope off his neck.

“Mr. Coughlin,” she panted, “don’t do it.”

Coughlin raised the rifle. “Yer on my land.”

“P-please.” She could barely get the word out. He wouldn’t shoot her, would he? “You have no right.”

“I have every right. This mutt has et his last chicken. Now get off my land.”

Slinky jumped joyfully against her pale yellow gown, planting muddy paw prints on the delicate chiffon. Coughlin yanked the dog back with a harsh jerk.

“No,” Felicity cried with frustration. How could she stop Coughlin? How could she prevent this murder? She looked around for help and spotted the broken fence ten feet back. “In case you haven’t noticed, we’re standing on parsonage property.”