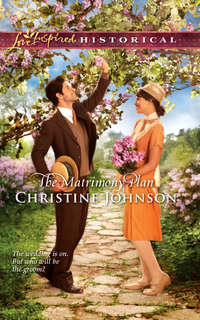

The Matrimony Plan

She sniffled. “That won’t help the holes or the dirt.”

“The words are still the same. I’m sure we can piece it together.”

She shook her head. “It doesn’t matter anymore.” Indeed it didn’t. She’d found her Mr. Blevins, and he was smiling at her. He might be a little less than elegantly attired, but he liked her. Surely he could love her. And she could clean him up. With a little effort, a decent suit and a haircut, he might pass as quite stylish. Yes, she could do this. In two months, maybe less, she’d be Mrs. Robert Blevins.

“Thank you,” she breathed, holding his gaze a bit longer than respectable.

His smile curled around her heart. “I’ll see you again?”

She nodded, and for a moment she thought he would take her hand, but then a motorcar horn honked. Not just any motorcar. Daddy’s Packard. After a backfire and a cloud of blue smoke, the car stopped and Daddy sprang out.

“Sorry I’m late, Pastor Gabriel.”

Pastor? Felicity reeled. This man she’d let take her hand, the one she’d promised to see again, was Reverend Meeks? He was supposed to be old and gaunt and ugly, not handsome and charming.

Her head whirled. She gulped the tepid air. Her ears rang. A minister. She’d agreed to see the new minister, her new minister, but her plan was to attract Mr. Blevins. Pastor Gabriel wouldn’t get her out of Pearlman; he’d tie her to the town—and Mother—forever. Her plan was ruined before it had even begun.

She stifled a sob, and then, as the world around her blurred, she did what any woman in such circumstances would do.

She fainted.

Chapter Two

Gabriel Meeks caught Ms. Kensington a moment after her eyes fluttered shut. She’d paled, and he rushed to her side, knowing she was about to faint.

Time paused the instant he touched her. Such beauty. Delicate veins laced her eyelids. Her ebony hair glistened, its tendrils like spring vines. The artist Alphonse Mucha could not have drawn a more beautiful woman.

The heady scent of roses overwhelmed his ordinarily good sense, leaving him gaping at her as seconds ticked away. From the moment he first saw her in the general store, he longed to know her better. Never did he imagine he’d hold this beauty in his arms. How perfectly she fit the cup of his shoulder and crook of his arm, as if God had made them two halves of the one whole.

“Lay her down,” barked her father, head of the Church Council, as he stripped off his jacket. “Get the blood flowing to her head.”

Though Gabriel wished he could hold her forever, he did as instructed, placing her head on the folded jacket. Spying the chewed envelope, he snatched it up and began fanning her face.

Still, she showed no sign of coming to.

“Do you have smelling salts?” he inquired.

Mr. Kensington shook his head and squatted beside him.

Gabriel fanned harder. Ms. Kensington hadn’t moved, and her color hadn’t improved.

“What if she doesn’t wake?”

“Don’t worry, son. She’ll come around in a moment. They always do. I’ve seen my share of ladies dropping off. Why I remember one dance where…”

Mr. Kensington’s story brought back a painful memory. Years ago, a girl who Gabriel had escorted to a dance claimed to feel faint. He left her on a sofa and went to fetch water. Upon his return, he spied her escaping to the garden with another man. His older brothers laughingly informed him that he’d just been initiated into high society. According to them, girls used this trick all the time, and he’d fallen for it. The humiliation still stung.

He hoped Ms. Kensington wasn’t that type of woman, but her expensive clothing and snobbish attitude put her squarely with the rest of the upper class. He’d been hoodwinked once. Never again.

“Perhaps we should fetch a doctor,” he said brusquely.

“Nonsense.” Kensington grabbed her handbag. “Let’s see if Felicity has some smelling salts with her.”

So her name was Felicity, meaning great happiness or bliss. Never had a name flowed so beautifully nor fit so poorly. This Felicity looked anything but happy. The only time she’d shown a glimpse of joy was when she chased the dog. Too bad it had vanished so quickly. Beautiful yet unhappy—how often Gabriel had seen that painful combination. He brushed a strand of silken hair from her eyes.

Kensington cleared his throat. “Pastor?”

He shouldn’t have done that. “I, uh, did you find any smelling salts?”

Kensington grinned beneath his mustache. “No, but she’s coming to, just like I said she would.”

The man was right. Felicity’s face had regained some color, and her eyelids opened, revealing splendid green eyes.

She flinched as if alarmed to see him and looked around. “Daddy? Wh-what happened?”

Disappointment knifed through Gabriel.

“You fainted, little one.” Kensington knelt beside his daughter, gently helping her to a sitting position.

His love for her was evident. She was cherished, the prize of his life, and completely spoiled. Such women brought nothing but trouble. Gabriel was better off without her.

“Can you stand?” Kensington asked her. “We need to get the pastor to the Ladies’ Aid Society meeting.”

Gabriel gulped. The Ladies’ Aid Society? He’d never been privy to that sacred enclave, but he’d heard tales. If the stories were correct, the ladies would have his entire life laid out for public display before the end of the afternoon. With any luck, that dissection would not include Felicity Kensington.

Felicity convinced Daddy to take her home. She couldn’t face Mother and the Ladies’ Aid Society, not in front of Gabriel.

Gabriel. Why did he have to be so handsome? She pressed into the dark corner of the Packard’s rear seat and watched him talk to Daddy. If he was nervous, he didn’t show it. She could grudgingly admire that quality. Most men cowered before her father.

But why had she agreed to see him again? She’d never be able to explain that to Mother, and it would ruin everything with Mr. Blevins.

Daddy stopped the car at the front door, and she scurried into the house before Gabriel could set a date. She slammed the solid oak door shut and leaned against its cool surface, but mere wood couldn’t quench the fire inside. Before Smithson or the cook or one of the other servants appeared, she retreated to the sanctity of her room and prepared a cold compress. She pressed it to her blazing cheeks, but even icy water couldn’t suppress the wild emotions.

A minister—she had been attracted to a minister. Not to say that there was anything wrong with the ministry but it just wasn’t for her. She had to marry wealth and privilege. She had to find a man who lived far from Pearlman if she ever hoped to escape Mother.

She unpinned the useless chignon and let her hair fall free. How could she have been so mistaken? He clearly wasn’t socially prominent—the dusty shoes, the rolled-up sleeves. But what pastor walked around so informally dressed? And with a Ladies’ Aid Society meeting to attend? Mother would tear him to pieces.

For a minute, she felt sorry for him. The ladies would gasp when he walked in, and Mother…well, no one should have to face that icy stare. Oh, Mother would speak with artificial politeness, but behind every word would be a barb, and at the next Church Council meeting, she’d petition for his removal. Poor Gabriel.

Poor Gabriel? What was she thinking? She’d promised to see him. Mother would have a conniption when she found out.

Felicity gnawed on her nails. Why had the church council hired a minister just out of school? There must have been older, better qualified pastors available, but no, they’d hired someone young and inexperienced and, well, handsome. Those curls, the twinkle in his eye, the hint of mischief… just thinking about him made her cheeks heat.

She dipped the compress in cold water, squeezed and re-applied.

His face had been the first thing she saw when she opened her eyes, and his concern had nearly melted her to the spot. She had to look away.

At first she’d been confused. How had she gotten on the ground? She didn’t feel any bruises or bumps, so someone must have caught her when she fainted. She prayed it was Daddy. Just the thought of Gabriel holding her sent hot shivers from her head to her toes.

There’d be no escaping the man or the rumors that would connect them. Practically the whole town had seen them together today including the Billingsley boy who clerked at the mercantile and Mrs. Evans. Felicity sucked in her breath. Mrs. Evans would tell everyone. All of Pearlman would know by tomorrow.

The trail of witnesses didn’t stop at the mercantile. Anyone at the businesses between the store and the train depot could have spotted them together, not to mention people on the street. And then there was the depot.

Her stomach flip-flopped. Maybe she was ill. Typhoid, influenza or scarlet fever would be better than facing the ridicule. Even Eloise Grattan, whose parents couldn’t buy her a beau, would snicker. And Sally Neidecker would lord it over her.

She groaned and sandwiched her head between two pillows. She could hear her childhood schoolmates now. Felicity and Gabriel, sweet as can be. Every childhood rhyme taunted her, each worse than the other. She needed to marry but not someone who would keep her in Pearlman the rest of her life.

What would Mother do when she found out? Felicity tossed the compress in her sink and paced back and forth across the room. Her mother would lecture and impose restrictions: no unsupervised walks, no unsupervised anything. How could Felicity meet the real Robert Blevins with Mother hounding her every move? It was terrible, horrible, the worst possible thing that could have happened.

She wrung out the compress, plopped on the bed again and pressed the cloth tight to her eyes. She needed a plan. A new plan, a better plan, one that could not fail.

The front door slammed. Mother. When that was followed by the strident ringing of the bell, she popped out of bed and re-pinned her chignon. A lady never has a hair out of place.

“Felicity,” Mother called out. “We need to talk.”

She knew. Daddy must have told her what had happened at the train station. Maybe Gabriel had spilled the whole story at the meeting. They’d doubtless had a jolly laugh over her while they sipped tea and downed Mrs. Simmons’s shortbread cookies.

Felicity tucked the last loose strand in place as Mother climbed the stairs. Thump. Thump. For such a small woman, Mother had a heavy step.

How could Felicity explain her reaction to Gabriel?

Thump. Thump. Mother’s steps matched Felicity’s heartbeat.

Heels clattered down the hallway.

Think.

“Felicity?” Mother threw open the door, her expression grim.

Too late. Felicity tried to swallow but her throat was dry. “What?” The word was barely audible.

“I told you not to walk to the meeting. I told you it would make you light-headed, and look what happened. You missed the most important meeting of the year. You left me alone. Why, if I hadn’t had Mrs. Williams’s support, you wouldn’t be chairwoman of the Beautification Committee. There wouldn’t even be a Beautification Committee. And the new minister. Felicity Anne Kensington. A lady always keeps her commitments.”

Felicity bore the lecture with bated breath, waiting for the worst to fall, but when Mother failed to mention anything about the train station or Daddy finding her with Gabriel Meeks, she relaxed.

“Thank goodness you have me to look out for your best interests,” Mother sniffed. “Change out of that filthy gown and try to make yourself presentable. We’re having a guest for dinner.”

A little knot formed in Felicity’s stomach. “A guest?” It had to be the new minister. Oh, how could she endure an evening with Gabriel Meeks? Daddy was bound to make a joke about finding them together. Mother would be horrified when she found out. Somehow she had to stop this dinner party. “Who’s coming?”

Mother ignored her question. “I wonder if he has Newport connections.”

“Newport?” Felicity gasped. “That’s not possible.” He was dressed too plainly to come from money, especially that kind of money. If only he didn’t have such a welcoming smile and warm brown eyes. The mere thought of him sent that peculiar hot and cold shiver through her again.

“Of course it’s possible. A man with his status could easily summer amongst the social elite. Hmm.” Mother surveyed her closet. “Nothing too fine in case he isn’t from proper society yet expensive enough to impress him if he is. Wear the pale green organdy.” She tossed the gown on the bed. “Traditional. You can’t go wrong with that.”

“Yes Mother.” It was always best to agree with Mother, especially when a greater concession was needed. “In fact, let’s put off the dinner until we know for certain.”

“Put it off?” Eugenia Kensington glared at her. “You can’t withdraw an invitation.” She pulled a pearl necklace from Felicity’s jewelry box and draped it around the neck of the dress. “Pearls will do quite nicely. I expect you downstairs by six o’clock. Try to display some of the social graces we paid for so dearly. Mr. Blevins might prove worth the effort.”

“M-Mr. Blevins?” Felicity stammered.

“Of course, Mr. Blevins. Who did you think I was talking about?”

Felicity averted her gaze, not wanting her mother to see that she’d been thinking about Gabriel.

Robert Blevins was coming to dinner. After such a disastrous day, she just might be able to salvage her plan. With any luck, she’d capture his affection before he learned about this afternoon’s fiasco.

Nothing about this first day had gone the way Gabriel anticipated. He came to Pearlman expecting a country church filled with salt of the earth, hardworking folk who would appreciate a down-to-earth sermon and a pastor who worked alongside them. The inequities and misery of the city wouldn’t exist here—no divide between rich and poor, colored and white, immigrant and citizen, and no stifling poverty or raging crime. The stains of abuse, liquor and hunger wouldn’t exist. In Pearlman, he could lead a church that would reach out to the sick and poor, taking them in and nurturing them into strong God-fearing people. It was the mission of his friend Mr. Isaacs’s Orphaned Children’s Society, and Gabriel planned to make it his own.

Today that idyllic image went right out the window.

The ladies at the meeting had pushed daughter after hapless daughter before him, but the only woman who’d touched his heart was proud and rich.

Then there was the parsonage. Instead of simplicity, he stood in a huge, two-story house large enough for a family of eight. The gleaming cherry Chippendale-style dining set and electric lighting looked to be recent installments, whereas the indoor plumbing had been in place for years judging by the mineral stains on the porcelain. The marble-topped sideboard and brocade-upholstered wingback chairs reeked of money. This was not a parsonage; it was a palace.

“Had my man put your trunk upstairs,” Branford Kensington said as he opened yet another door. This one led to a handsome library and study. “Encyclopedia, concordance and the Bible in the proper translation.” The man blustered around the room like a bull moose. “Of course there’s room for your books—” he patted the one empty shelf “—though judging by the size of your trunk, you won’t need all this space.” He laughed at his own joke.

Gabriel swallowed his irritation. “I guess you’re correct there.” He’d only brought the necessities, not wanting to put off any of the congregation with his upper-class background.

“I’ll give you until six o’clock and then send Smithson down. Come on up to the big house for dinner. Consider it a standing invitation until your housekeeper arrives.”

“Housekeeper? I don’t—” Gabriel started to correct him, but Kensington had already moved on.

“Fenced yard was installed some years back for Reverend Johanneson. He had four children and thought it would keep them out of mischief.” He chuckled at the memory. “Land goes clear to the river.”

Gabriel peered through the crystal-clear kitchen window. “It’s a fine piece of land.”

“Yes, it is.” Kensington stuck out his hand. “Well son, I’ll leave you to settle in. Smithson’ll be here with the car at six sharp.”

Gabriel blanched at being driven by a chauffeur. People would talk. “No, that won’t be necessary. I’d rather spend a quiet night.”

“Nonsense. My wife will have my head if you don’t come.”

Gabriel hesitated. An evening with Branford and Eugenia Kensington promised to try the patience of a saint. He’d barely made it through the Ladies’ Aid Society meeting.

“You’ll want to check on Felicity,” Kensington noted with a wink, “to see if she’s recovered.”

Memories of her flooded back: eyes the color of watercress and an elegance seldom seen in small towns. If Gabriel was honest with himself, he did want to see her. “Six o’clock?”

“I’ll send the car.”

Gabriel shook his head. “I prefer to walk. Just give me the address and point the way.”

“Walk, eh?” Kensington eyed him with what seemed to be new respect. “Physical exertion builds a man’s character. I recall my trek up Kilimanjaro in 1898—”

“Thank you, sir.” Gabriel was too tired for a lengthy story. “The address?”

“Oh, ahem.” Kensington cleared his throat. “Naturally you’ll want to freshen up first. It’s the big Federal on top of the hill. Can’t miss it. Twin lions at the head of the drive.” He nodded slightly and took his leave.

The house quieted after Kensington left. Gabriel drank in the solitude, spending time in prayer while he unpacked. As he half filled two of the bureau’s four large drawers, he wondered if he had made a mistake coming to Pearlman. Mr. Isaacs had asked Gabriel to join him at the Orphaned Children’s Society back in New York City.

“We could use a man like you,” Isaacs had said. “You’ve volunteered here for years, and your seminary experience would be a plus. There are other places besides the ministry where you can do God’s work. You’d be a splendid agent for the children.”

As much as the offer tempted Gabriel, he had to decline. “I need to go to Pearlman. God has called me to pastor there. I don’t know why, just that I must go.”

Isaacs had understood, as always. “Go then, with my blessing, but if you ever feel your task there is complete, the offer stands.”

After today, Gabriel wondered if he misunderstood God’s call and should have accepted Mr. Isaacs’s offer.

“Why did you bring me here, Lord?” Gabriel asked as he shut the drawer. Today had given him no clue, and the silence of the huge house didn’t either. He thought Pearlman might bring him the good, honest wife he’d longed to meet, but instead he’d found Felicity Kensington. For all her beauty, she would never make a good minister’s wife. She was too concerned about appearances.

He sighed and walked to the parlor. From the front windows, he could see Main Street and the church’s steeple above the rooftops. To the right sat a pretty little park, wooded along its edges and studded with lilac bushes and iris in bloom. He envisioned picnics and revivals, music, laughter and children playing.

Strange to place the parsonage so far from the church. It must be a good two blocks away. From what he’d seen, the parsonage was one of the last homes before farmland. And the property stretched back into the trees. What had Kensington said about a river?

For as long as he could remember, his parents had taken the family to the Catskills in the summer. The cabin emptied onto a lake filled with trout and bass. Gabriel had spent long hours swimming and fishing in that lake. Maybe this river had good fishing. He’d take a look.

The kitchen door opened easily, but the screen door stuck and squeaked. He’d mention it to the church trustees. Two concrete steps led down to the fenced yard. He stretched his back and surveyed the grounds. Other than an overgrown lilac and four-strand clothesline, the yard was bare. The whitewashed picket fence looked solid enough, probably recently painted. Gates pierced both sides and the end.

Beyond the far gate stood the forest, sparse at first but thickening to dense woods. He headed that way, passed through the gate and stepped into the wildness beyond. He clambered over fallen logs and crashed through the undergrowth. When he reached the edge of the river, he dropped to a lichen-covered log to watch the water flow past. He didn’t see any fish, but they’d be there in the deep pools.

The river ran dark green over a stony bottom. In the shallows, the color turned to brown, though in a few places it glistened light green over a patch of sand. The same green as Felicity Kensington’s eyes.

The thought sent an unwelcome ripple of pleasure through him. He tried to shake some sense into his head. Felicity was precisely the wrong type of woman: rich, controlling parents; a highly cultivated sense of superiority; a society girl. No matter how lovely, Felicity Kensington was one temptation he should avoid. If only he hadn’t agreed to dine at the Kensingtons’ house tonight.

Lord, lead me not into temptation. But how?

He watched the rustling treetops. They gave no answer. Neither could he hear God’s still, small voice. With a sigh, he roused himself. He’d accepted and must attend. Until then, he could take solace in the river. He followed the riverbank away from the park, occasionally peering into the depths to look for fish.

Within minutes, he reached the edge of the wood and the end of the path. A half-fallen barbed-wire fence blocked the way. Since the post had rotted away and the path clearly continued on the other side, Gabriel figured the owner must not have gotten around to removing it.

Two steps into the field, he heard a gun being loaded. Every hair rose on back of his neck.

“Hello?” He slowly lifted his palms to show he was unarmed and looked for the source of the threat. “I’m Reverend Meeks, the new pastor.” Never had he been so glad to use the title.

“I dun’t care who y’are. This here land’s private. Coughlin land, and dun’t ye forget it.” A narrow-eyed, dungaree-clad man climbed up from the riverbank, shotgun pointed directly at Gabriel.

“Sorry. It looked like the path continued.”

“You city folk don’t know what a fence is?” He waved Gabriel back with the tip of his gun.

“Uh, I guess not.”

“Well, lemme learn you up. This here fence marks my property, Mister Reverend. You stay on your side, and I stay on mine. Understand?”

Gabriel stepped back over the fallen fence, but he didn’t dare bring his hands down yet. “I thought the fence was abandoned.”

The man’s bulbous nose shone red in the sun. “It’s them criminals. As soon as I put it up, they take it right back down.”

“Criminals? Here?” Though Gabriel had only been in town a few hours, he had a hard time believing it supported a large criminal population.

“City folk.” The man spat and aimed his shotgun at Gabriel’s head.

“Don’t shoot!” Gabriel jumped back, nearly tripping on an exposed root.

The man lifted the gun higher and fired. With a derisive cackle, he said, “I was jess going for a squirrel.”

Gabriel’s heart pounded so hard that he could barely speak. “Did you get it?” The question barely fit through his constricted throat.

“Naw. Too devilish fast for this old gun.” He shook the discharged shotgun. “R’member. You stay on your side, and I stay on mine.” With that declaration, he headed across the field to the distant ramshackle farmhouse.

“Pleased to meet you, Mr. Coughlin,” Gabriel called out.

The man either didn’t hear or didn’t want to. Peculiar man. Peculiar town.

Chapter Three

“You did what?” Mother’s screech carried all the way upstairs.

Felicity checked the clock. It was not yet five forty-five. Mother’s conniption fit couldn’t be about her. She eased the emerald-colored taffeta jacket over her shoulders. Conservative would no longer do. She had to dazzle Robert Blevins tonight, before he heard any malicious gossip connecting her to Gabriel Meeks.