Полная версия

The Isles of Scilly

As the former Duchy Land Steward wrote, ‘the weather in Scilly is characteristically unpredictable’ (Pontin, 1999). Gales and strong winds over force 8 are a frequent feature, and not just in winter: gales can happen throughout the year. Visitors can sometimes find themselves marooned on the island they are staying on for several days when the boats stop plying due to rough seas. Some of us have considered this a bonus at times!

THE SCILLONIANS

The Isles of Scilly have had almost 4,000 years of continuous occupation since the arrival of Bronze Age farmers (Thomas, 1985), but for centuries before that nomadic people who left little sign of their presence other than a few flints had visited the islands. The population has fluctuated and there have been many incomers over the centuries. Not many of the current families can trace their ancestors back more than a few hundred years, usually to the 1640s or 1650s (court records show the Trezise family was in the islands in the thirteenth century). Some are probably descendants of soldiers who came to man the Garrison and married local women. The inhabitants of St Agnes used to be known as Turks as they tended to be short and swarthy and were reputed to have had an exotic ancestry. As on other British islands such as Orkney (Berry, 1985) there has been a continuous stream of people, including Neolithic visitors, Bronze Age and Iron Age inhabitants, pirates, smugglers, Cromwellian soldiers, Royalists, French traders, British servicemen in both World Wars, land-girls, and men and women who came to staff hotels and other establishments. Many of these peoples stayed, married locals, and their descendants have added to the rich mix of heritage in the population.

Population

The resident population of the islands has stayed at around 2,000 for many years. Of these about 1,600 live on St Mary’s, with about 160 on Tresco and 100 on each of the other inhabited islands (St Martin’s, Bryher and St Agnes). During the summer holiday season visitors approximately double the population.

The Duchy of Cornwall

The Isles of Scilly became part of the original Duchy of Cornwall in 1337 when Edward, the Black Prince, became the first Duke of Cornwall. Today the islands are still owned by the Duchy, administered by a resident Land Steward. The Duchy is governed by a Council, of which His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales and Duke of Cornwall is Chairman. Much of the land on the inhabited islands is in agricultural tenancies, with the exception of the island of Tresco, which is leased to the Dorrien-Smith family, and Hugh Town, which became freehold in 1949 (Mumford, 1987). In 1999 there were some sixty farm-holdings, covering 557 hectares, of which 182 are in horticultural use, mostly bulbs. The average farm on the smaller islands of Bryher, St Agnes and St Martin’s is very small, sometimes less than 10 ha, although those on St Mary’s and Tresco are proportionately larger. Many fields are equally small, some less than 0.1ha (Pontin, 1999). Some 1,845 hectares of the unfarmed land are now leased to the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust, mostly heath, wetland and coast on the inhabited islands and including all the uninhabited rocks and islands.

The Council of the Isles of Scilly

The Council of the Isles of Scilly is a unitary authority (Local Government Act 1972, as applied by the Isles of Scilly Order 1978). This means the Council has unusual powers in that it has all the functions of county, district and parish councils as well as replacing the Environment Agency and the airport authorities in the islands. The islands are not automatically included in all national legislation. There are sometimes specific references or amendments to ensure that legislation also refers to the islands.

TRAVELLING TO THE ISLES OF SCILLY

These days getting to Scilly is no longer the difficult and chancy business it was in the past, and we can easily forget that for earlier visitors the journey was frequently an ordeal. Passengers could arrange to go by sailing ship to the islands, but it was not until the start of the regular mail boat after 1827 that there was an organised service from Penzance to St Mary’s. Even so the passage usually took eight to nine hours and at times as much as two days. Things picked up when a steamer service started about 1858, and a year later the railway was extended to Penzance. Then in 1937 the air service started linking Scilly with the mainland, offering an alternative and much quicker route for those reluctant to brave the sea crossing.

The RMV Scillonian (Fig. 6) is the third of that name to have carried freight and passengers between Scilly and the Cornish mainland. She sails most days (except Sunday) between spring and autumn, the crossing taking about two and a half hours according to conditions. The Scillonian is notorious for her rolling motion, which is due to her shallow draft, designed to enable her to enter the shallow waters around the islands; but the possibility of seeing unusual seabirds, cetaceans and other excitements during the passage makes her popular with many visitors. The alternative routes to Scilly are by air, either fixed-wing plane or helicopter, both of which take about twenty minutes; but neither flies if there is fog. Flying is the only route in winter when the Scillonian is laid up. A second ship, the MV Gry Maritha, now transports most freight to the islands. Inter-island launches meet the ships in St Mary’s and transfer goods of all kinds to the ‘off-islands’, as the other four inhabited islands are known locally.

FIG 6. The RMV Scillonian in harbour after her two-and-a-half-hour sail from Penzance. July 2006. (Rosemary Parslow)

Tourism

It was not until after World War II that Scilly became really popular as a holiday destination, with hotels and guesthouses opening up to accommodate many more visitors, including many naturalists. In 2003 Scilly attracted 122,000 visitors (Isles of Scilly Tourist Information). Tourism now accounts for some 85 per cent of the island economy, although apparently a significant amount of the profits goes off the islands to the mainland-based owners of holiday property and hotels. Most visitors stay in holiday accommodation on the islands, including hotels, guesthouses, cottages and camp sites. Others arrive and stay on their yachts and motor cruisers.

THE UNIQUENESS OF THE SCILLONIAN FAUNA AND FLORA

We will see in later chapters that the Isles of Scilly aptly demonstrate the phenomenon of island biogeography. In all groups of flora and fauna there is a paucity of species compared with Cornwall, and this is a theme to which we will return. This paucity is readily attributed to the distance from the mainland, the much smaller land area and the limited range of habitats compared with those in Cornwall, with no rivers, only a few tiny streams, no acidic mires (bogs) and only granitic bedrock, with none of the slates, serpentinite and other rock types of the mainland. Widespread exposure of habitats on the Isles of Scilly may also account for the absence of some species that are susceptible to wind-blown salt spray. For example there are currently about 217 bryophyte species (57 liverworts, 3 hornworts, 157 mosses). Of these, six liverworts and five mosses are species introduced in Britain. Compared with Cornwall the total bryophyte flora is much poorer, with only about 36 per cent of the overall Cornish total of 167 liverworts (including hornworts) and 37 per cent of the total of 430 mosses. Scarcity of basic soils on the Isles of Scilly may also account for the absence of some other species common in Cornwall.

The number of species of land birds in Scilly is also small. Visitors to the islands are usually surprised to find many common passerines, let alone owls and woodpeckers, missing or in very low numbers. Equally the very confiding nature of blackbirds Turdus merula and song thrushes T. philomelos will soon be remarked on. The Isles of Scilly have hardly any land mammals, and no predators such as foxes Vulpes vulpes or stoats Mustela erminea. There are no snakes and very few resident species of butterflies or dragonflies; this is common for all groups. But on the other hand there are species that are only found in Scilly, such as the Scilly shrew Crocidura suaveolens cassiteridum, several rare lichens and many other examples of interesting and uncommon species.

Lusitanian and Mediterranean influences

References will be made in the following chapters to Lusitanian influences. The geographical position of the Isles of Scilly has led to a number of unique aspects of the flora and fauna. Many species are at their northern limit in Scilly and southwestern Britain. These are species from the Atlantic coastal regions of southern Europe, based on the former Roman province of Lusitania, and into the Mediterranean. A visit to parts of Spain or Portugal will reveal many species of plants that are commonly seen in Scilly, but that are rare of absent from the rest of Britain. There are also lichens, invertebrates and other groups with Lusitanian species that reflect the same distribution, and in the marine environment many species found in southern or Mediterranean waters that also occur in the Isles of Scilly and the Channel Islands. In the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora (Preston et al., 2002) the floristic elements of the flora are described: the Mediterranean-Atlantic and Submediterranean-Subatlantic are plants that are associated with these biogeographical regions.

NATURE CONSERVATION DESIGNATIONS

Currently the Isles of Scilly are covered by a plethora of designations relating in some way to nature conservation.

The whole coastline of the Isles of Scilly was designated a Heritage Coast in 1974.

Scilly is a candidate Special Area of Conservation (cSAC) under the European Habitats Directive.

A Special Protection Area (SPA) (for birds) covers 4.09km2.

Scilly is a Ramsar site, an international important-wetland designation.

Scilly was designated a Conservation Area in 1975.

Twenty-six sites have been designated Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) by English Nature. Of these five are geological sites.

The Isles of Scilly has been a Voluntary Marine Park since 1987 – this includes the whole area within the 50m depth contour line.

Scilly was designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1975 – it includes ‘all the islands and islets above mean low water that together form the Isles of Scilly’. The total area covered is 16km2. Scilly is the smallest AONB in the country; also the only one under a single local authority. The Management Plan for the AONB was published in 2004.

STUDYING THE FLORA AND FAUNA OF THE ISLES OF SCILLY

Although many of the visitors to the Isles of Scilly over the centuries have commented on the natural history of the islands, most of what has been written has concentrated on the most obvious groups. Authoritive books have covered plants, birdlife, butterflies and moths, but many of the marine species, insects and more difficult groups are the subject of papers in scientific journals or rather inaccessible unpublished reports held by English Nature and other bodies. Recently there has been a resurgence of interest in these other groups, especially invertebrates and marine life, which had otherwise been left to a small number of specialists.

For many years botanists have been well served by a Flora (Lousley, 1971), but it is now due for an update as there is a great deal of new botanical information available. Some plant hunters whose aim is to record rare plants, and especially alien species, are regular visitors to the islands.

Birds have tended to attract the lion’s share of attention since the late 1950s, when the St Agnes Bird Observatory became a focus for birdwatchers hoping to see rare and unusual migrant and vagrant species. October is still the most popular month for birdwatchers to visit Scilly. This is an extraordinary phenomenon; it has to be seen to be believed. Hundreds of enthusiasts, bristling with telescopes, pagers and binoculars, arrive in Scilly intent on seeing rare migrant birds. These birders mostly have well-defined patterns of behaviour, usually travelling en masse to wherever there is news of some exciting bird. So it is not unusual to see them all gathered in one place, behind lines of telescopes waiting patiently for a glimpse of their quarry. In the evenings many will attend the ‘count’, when the tally of the day’s finds are recorded.

The marine habitat might seem to be rather neglected. Although there are organised field trips to Scilly to study marine ecology, most of the information stays in student dissertations. But for every child visiting the islands half the fun is exploring rock pools. Now, with plenty of opportunities to dive or snorkel, the underwater life is becoming much better known. Underwater safaris, glass-bottomed boats and swimming with seals and seabirds are making this fascinating medium much more accessible to the general public.

Some of these visitors to Scilly are going to take more than a casual interest in what they see. Hopefully they will contribute records and notes that will lead to further expansion of our knowledge of the natural history of the islands. Since its inception the Isles of Scilly Bird Group has produced a report that also includes notes, short papers and reports on natural history subjects other than birds – the Isles of Scilly Bird & Natural History Review. Perhaps this book too will encourage an interest in the fascinating natural history of the Isles of Scilly.

The chapters that follow are arranged to give an overview of the geology, something of the history, the people who contributed to our knowledge of the natural history of the islands, the individual islands, the main habitats, and the major groups of flora and fauna. Descriptions of some of the plant communities are included as an appendix.

CHAPTER 2 Geology and Early History

There are signs of Bronze Age man on every island in Scilly.

Charles Thomas (1985)

GEOLOGY

AT FIRST GLANCE the Ordnance Survey’s geological map of the Isles of Scilly appears to be something of a disappointment: almost the whole of the land shown on the map is coloured in the same shade of red-brown, representing granite. A granite batholith, the Cornubian batholith, extends as a series of cupolas or bosses along the Southwest Peninsula from Dartmoor to Land’s End and the Isles of Scilly, ending at the undersea mass of Haig Fras 95km further on and slightly out of line, presumably due to faulting (Edmonds et al., 1975; Selwood et al., 1998). Originally the rocks were a softer, slatey rock called killas; this was altered by pressure from the granite boss as it was extruded and pushed up into the killas, which was later eroded and now only exists as rock called tourmalised schist, found as a narrow dyke-like patch on the northwest of St Martin’s (Anon., Short Guide to the Geology of the Isles of Scilly).

The Scilly granite is very similar to that found in Cornwall, and was classified by Barrow (1906) into different types, the main ones being the older, coarse-grained G1, which is found mainly around outer the rim of the islands, and G2, which is finer-grained and is mostly in the central part of the islands and has often been intruded into G1. The two types of granite merge into each other without any obvious line of demarcation. Characteristically the granites are made up of quartz and crystals of feldspar, muscovite mica, biotite mica and other

FIG 7. Loaded Camel Rock at Porth Hellick, St Mary’s, May 2006. (Richard Green)

minerals. Much of the rock is beautifully striped through with veins and dykes, mostly narrow and usually white or black according to the infilling; white quartz or black tourmaline crystals can be found in these dykes, and rarely larger crystals of amethyst quartz. A vein of beautiful amethyst quartz that runs through some of the rocks to the north of St Agnes at one time had large, visible crystals, but most have since been taken by collectors. It is still possible to find smaller veins of crystals, and some beach pebbles have small layers of crystals running through them.

Another characteristic of the granite is the weathering along the veins and softer areas in the rock. The cooling and pressures have already formed these into very distinctive vertical and horizontal cracks, and erosion by weather and the sea then combine to produce the most extraordinary natural sculptures. Some of the most impressive examples can be seen on Peninnis Head and along the east coast of St Mary’s, but all the islands have examples. Some of these rocks have been given fanciful names: Pulpit Rock, Monk’s Cowl, Tooth Rock, Loaded Camel (Fig. 7). A curious type of formation seen frequently in Scilly is a rock basin in the top of a granite boulder where rainwater has weakened feldspar and released quartz crystals, which apparently have blown round and round to form a natural bowl.

Surface geology

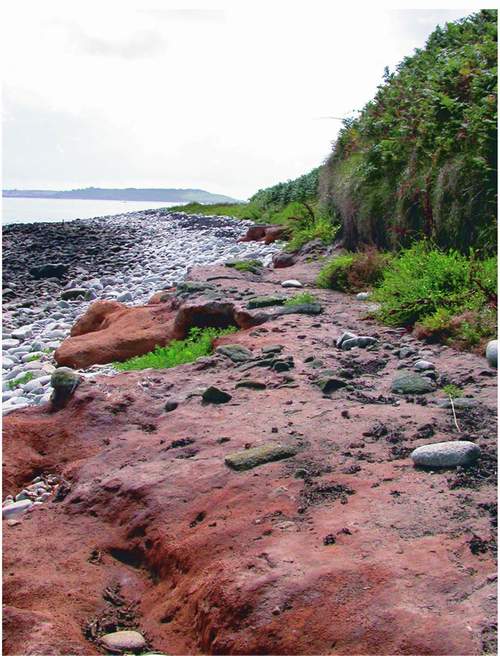

When the granite weathers it eventually becomes reduced to sand. Blown sand is an important constituent of the soils of all the islands as well as forming the beautiful white beaches and the sand bars that link many of the higher parts of the islands. Ram (also known as head or rab) is a cement-like material formed by the breakdown of periglacially frost-shattered granite fragments that forms deposits around the bases of granite carns, in valleys and especially in the cliffs (Fig. 8). It is often excavated from ‘ram pits’ to be used by the islanders as a mortar in building work and sometimes as a road surface. Alluvium is found under the Porthloo fields, and at Lower and Higher Moors. Small patches of gravel found near the daymark on St Martin’s and at a few other places are probably of glacial origin – see below.

FIG 8. Ram shelf at the base of the cliff on Samson. (Rosemary Parslow)

FIG 9. An example of a raised beach at Porth Killier, St Agnes, where former beach levels can be seen above the present beach. May 2003. (Rosemary Parslow)

Raised beaches

Raised beaches are especially common throughout the southwest of Britain, and the Isles of Scilly have many examples. The raised beach at Watermill is a classic site with a conglomerate of clast-supported rounded cobbles and boulders, overlain by well-sorted medium sand (Selwood et al., 1998). There are many places all around the coasts in Scilly where former shore levels with beach deposits are exposed in the cliffs above the present beaches. There are raised beaches at Hell Bay, Bryher; Porth Killier, St Agnes (Fig. 9); Piper’s Hole, Tresco; Shipman Head, Bryher and many other places.

Glaciation

Although it was long thought that glaciation had missed Scilly, there is evidence that a tongue of ice from the southern edge of the Late Devensian ice sheet, the Irish Sea Ice Stream, probably reached the northern islands of Scilly 18,000 years BP (before present), eventually leaving deposits on White Island off St Martin’s, and on Northwethel (Scourse et al., 1990). The evidence for this lies in a great variety of rocks exotic to Scilly such as flint, sandstone and associated ‘erratics’. The best example of glacial till in the islands is within the Bread and Cheese

FIG 10. The bar to White Island is a former glacial feature, probably a glacial moraine. June 2002. (Rosemary Parslow)

formation at Bread and Cheese Cove SSSI on the north coast of St Martin’s: the overlying gravels, the Tregarthen and the Hell Bay gravels, are interpreted as glaciofluvial and solifluction deposits respectively. There are erratic assemblages with both deposits (Selwood et al., 1998). Recent work suggests that some of these deposits, such as that at Bread and Cheese Cove, may not be in their original positions (Hiemstra et al., 2005). Other sites with glacial links occur in the bars in the north of the islands, such as the ones at Pernagie, the one connecting White Island to St Martin’s (Fig. 10), and Golden Bar, St Helen’s: these are probably glacial moraines, not marine features (Scourse, 2005).

EARLY HISTORY – THE SUBMERGENCE

Twenty thousand years ago most of Britain was under the last glaciation, extending as far south as the Wash and south Wales. At this time sea level would have been as much as 120m below Ordnance Datum. Then the climate ameliorated and by 13,000 BP the Devensian ice had almost disappeared (Selwood et al., 1998).

Four thousand years ago, before the sea inundated the land, Scilly would have had a very different landscape, with low hills and sand dunes surrounding a shallow plain (Fig. 11). Based on the present-day undersea contour lines, there would at that time have been three main islands: the principal one would have included the present-day St Mary’s, Tresco, Bryher and St Martin’s, the Norrard Rocks, the Eastern Isles and the St Helen’s group; Annet and St Agnes would have made up a smaller second island group; and the Western Rocks would have been the third. Later the islands became parted as the sea rose still further. The long isolation of St Agnes from St Mary’s and the rest of Scilly may possibly explain the differences in the flora – for example why the least adder’s-tongue fern Ophioglossum lusitanicum is restricted to St Agnes.

Most accounts of the submergence of the Isles of Scilly are based on the model proposed by Thomas in Exploration of a Drowned Landscape (1985). Thomas suggests that sea level rose rapidly and reached to within a few metres of present-day levels by 6000 BP, although final submergence of the island of Scilly to

FIG 11. A map showing how the main islands may have appeared prior to the submergence. (After Thomas, 1985)

create the present archipelago may not have been effected until post-Roman times. Archaeological and historical evidence show that although sea was rising on a unitary island about 2000 BC, ‘submergence began in earnest during Norman times and was effectively completed by the early Tudor period’ (Thomas, 1985; Selwood et al., 1998). However, Thomas recognised that although his model assumes a gradual process of submergence, there is an alternative picture with a series of dramatic events such as tidal surges. According to Ratcliffe and Straker (1997), submergence may have been even more gradual than Thomas proposes. The most controversial aspect of Thomas’s model is his suggestion that separation of the islands did not occur until early Tudor times. Although the exact details of when and how the marine inundation took place are unclear, remains of huts, walls and graves on areas now covered by the sea are irrefutable evidence that it took place.