Полная версия

The Isles of Scilly

Collins New Naturalist Library

103

The Isles of Scilly

Rosemary Parslow

Editors

SARAH A. CORBET, ScD

PROF. RICHARD WEST, ScD, FRS, FGS

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIBIOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIHORT

PROF. JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native flora and fauna, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Editors

Map

Editors’ Preface

Author’s Foreword and Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1 An Introduction

CHAPTER 2 Geology and Early History

CHAPTER 3 Later History - People and Their Influence on the Islands

CHAPTER 4 Naturalists and Natural History

CHAPTER 5 St Mary’s

CHAPTER 6 The Off-Islands

CHAPTER 7 The Uninhabited Islands

CHAPTER 8 The Sea and the Marine Environment

CHAPTER 9 The Coast

CHAPTER 10 Grassland and Heathland

CHAPTER 11 Woodland and Wetland

CHAPTER 12 Cultivated Habitats - Bulb Fields and Arable Plants

CHAPTER 13 Gardens

CHAPTER 14 Insects and Other Terrestrial Invertebrates

CHAPTER 15 Mammals, Reptiles and Amphibians

CHAPTER 16 Birds

CHAPTER 17 The Future

APPENDIX Vegetation Communities

References and Further Reading

Species Index

General Index

The New Naturalist Library

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

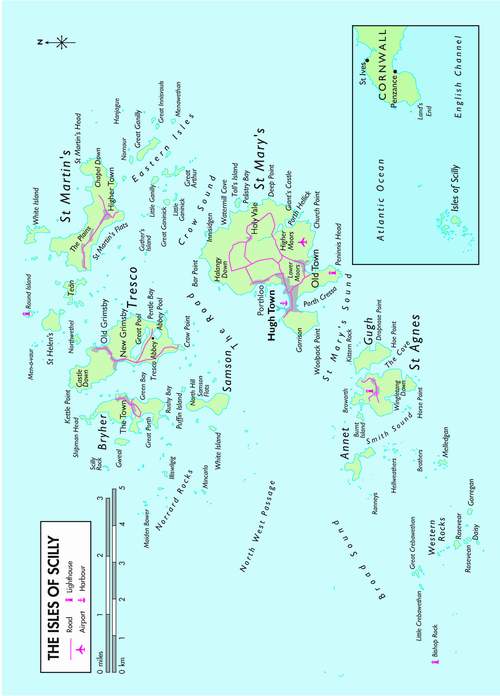

Map

Editors’ Preface

EARLIER VOLUMES OF the New Naturalist library have concerned the natural history of the islands of northern Britain – the Highlands and Islands (1964), Shetland (1980), Orkney (1985) and the Hebrides (1990). Here, in the Isles of Scilly, a group of islands at the extreme southwest of Britain presents a totally different aspect of island natural history.

Any account of the natural history of the Isles of Scilly has to comprehend an unusually wide variety of life and environments. In this striking archipelago of inhabited and uninhabited islands, southwest of Land’s End and on the fringes of the Atlantic, marine and terrestrial natural history are intimately connected. The oceanic climate, with mild summers and winters and stormy weather, exerts a strong influence, resulting in a flora and fauna unique in Britain. Added to this is the effect of thousands of years of human occupation, governed by changing economic conditions and isolation from the mainland, a history which has produced, for example, an extraordinary mix of native, introduced and cultivated plants.

The author, Rosemary Parslow, has an unrivalled knowledge of the natural history of the Isles of Scilly, gained over nearly fifty years of active involvement in observation and survey. Her studies have included the marine life and the life of terrestrial environments, including both fauna and flora. With such a range of practical experience, she is in an excellent position to give a synthesis which covers the variety of natural history of the islands, as well as issues of conservation and future development. Such a synthesis will be welcomed by Scillonians and by the many visitors to the islands, as well as by those with wider interests in the British fauna and flora.

Author’s Foreword and Acknowledgements

HOWEVER OFTEN YOU go to Scilly it is still a magical experience as the islands slowly emerge out of the line of clouds on the horizon, to resolve into a mass of shapes and colours against the sea and sky. Whether you go there by boat, stealing up gradually on the islands, or by air, flying in low over the coastline of St Mary’s to land with a rush on the small airfield – like one of the plovers that feed there on the short turf – it brings a thrill of excitement every time.

I first went to Scilly in 1958, to stay at the St Agnes Bird Observatory that had started up the previous year. It was an ‘un-manned’ observatory, run by a committee of enthusiastics, organising self-catering holidays for groups of bird-ringers to operate it as a ringing station over the spring and autumn migrations. The first year had been based in tents at Lower Town Farm, but by the time of my visit they were renting the empty farmhouse. Like many similar establishments they ran on a small budget and lots of commitment; the living conditions were very basic, but the surroundings idyllic. That first visit was the start of a lifetime love affair with Scilly, which has influenced my whole adult life and has led to writing this account of the natural history of the islands.

Those early visits were made when I was working as a very junior scientific assistant at the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington. At that time collecting specimens was still an important element of the work, in order to build up the Museum’s taxonomic collections. So staff holidays often became unpaid collecting trips, and mine were frequently timed to go to Scilly at the best times for ‘shore collecting’, to collect marine invertebrates. These were when the equinoctial spring tides occur, around Easter and again in autumn, when the most extensive areas of shore are exposed. This was in the days before cheap wet suits and underwater photography meant that marine biologists were no longer constrained by tides. At that time it was boulder-turning and wading and following the tide down to the lowest level accessible, laden with heavy collecting gear. Most of the collecting I did was to order: specific groups of animals were targeted because these were ones where information on their distribution and status was needed, as well as adding representative specimens to the Museum collections. This resulted in a series of Isles of Scilly collections in the 1960s and ’70s, mostly shore fishes, sponges, worms, and other invertebrates, especially echinoderms, my specialist group.

Even after I had left the Museum, a colleague would send a small milk churn packed with collecting paraphernalia to the island of St Agnes to await my arrival for the family holiday, and then we would return it with the carefully preserved and labelled specimens packed inside. This system usually worked very well, but in the early days there were some hiccups – like the time the churn was nearly dispatched to Sicily due to a misunderstanding with the carriers, or the year it was put back on the launch by a puzzled islander because he did not know anyone who used milk churns on the island!

This first-hand experience – firstly the shore collecting, then the species records when collecting specimens became unfashionable, my involvement with the bird observatory, and then starting listing plants – was fortuitous in that it gave me a unique opportunity to study, photograph and get to appreciate the wildlife, scenery and history of these enchanting islands. I have been fortunate in that I was also to spend many weeks over the succeeding years on Scilly, usually based on St Agnes, and later St Mary’s.

Since those early days I have visited the islands at least once every year (except for a break of a couple of years in the late 1960s), have had several prolonged stays, and have been there in every month of the year and probably most kinds of weather. This has probably been the best way of getting to know as much as possible about the islands without being resident there. At various times I have been employed to survey and produce reports on a number of subjects from bats to plants. In 2002 I was commissioned to write a Management Plan for the land leased by the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust. This gave me a further opportunity to spend a longer time on the islands, getting to know them, their habitats and the people whose job it is to manage those habitats (Parslow, 2002).

Due to the climate and the geographical position of the islands there are some species, particularly plants, which are not usually easy for the holiday visitor to see. Certainly if you want to see some of the plants which flower in the middle of winter, such as some of the introduced aliens, German ivy Delairea odorata and some of the Aeoniums, then a visit at Christmas or New Year is essential. This is also a good time to find the tiny least adder’s-tongue fern Ophioglossum lusitanicum, a great rarity found in Britain only on the Channel Isles and on St Agnes in Scilly. Every month has its specialities, so there is always something to look out for at any time of the year. If your interests are more ornithological then everyone will recommend the spring and autumn migrations for the ‘falls’ of unusual migrants. In summer there are breeding seabirds, and a boat trip can take you out to see puffins, shags, guillemots, fulmars and other seabirds among the uninhabited islands – and there are also grey seals hauled out among the distant rocks. Even in winter there are peregrine and raven to look out for, and sometimes in cold weather large numbers of woodcock seem to fall out of the sky. For the other natural history groups, lichens, insects, fish or seaweeds, there are nearly always things to do and things to see!

It is not possible to write about the flora and fauna of the Isles of Scilly without considering all the other aspects that go to make them so unique. Their geography, geology and climate are intimately bound up with the history of the people of the islands, the way they have used the land, and present-day management. Over the next few chapters we will consider many of these aspects of the islands, as well as the major habitats found in Scilly – the heathlands, coastland, cultivated fields and wetlands. Each of the islands has its own unique character and special plants and animals – from St Mary’s and the inhabited smaller ‘off-islands’ to those uninhabited islands and rocks which are home to the rest of the islands’ wildlife. Then there are those people who have been important in the study of the island flora and fauna, the story of the rise in popularity of the islands for birdwatchers, the effect climate has had in shaping the flora and the escapes from cultivation which have now become established as part of the landscape. The sum of all these is what makes up the fabric of these unique and beautiful islands, the Isles of Scilly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Compiling this book has taken a long time; it represents several decades of involvement with the Isles of Scilly, and it would never have been written without the help and encouragement of many people. There are too many individuals to mention everyone, but I hope that they will understand that I am hugely grateful to them all. The real generosity of those naturalists who allowed me free access to their work and who commented on sections of the text has made it possible for me to include many aspects of flora and fauna about which I know very little.

The artwork in this book has been selected from a huge volume of material I have been offered; unfortunately I could only use a small selection. Many of the photographers and artists also helped in other ways, with information and comments. For permission to use their material I would like to acknowledge Andrew Cooper, Paul Gainey, Sandra Gibson & Frank Gibson (Gibson Collection), Martin Goodey, Richard Green, Mark Groves, Alma Hathway, Ren Hathway, David Holyoak, Chris Hopkin, David Mawer, Paul Sterry, Bryan Thomas, Ian Wallace, the Isles of Scilly Museum (for Hilda Quick woodcuts) and the Cornwall Archaeological Unit and Jeanette Ratcliffe. I consulted libraries at the Cornish Studies Library, Redruth, the Natural History Museum, London, and English Nature (now Natural England), Truro.

I am very grateful to the many people in the Isles of Scilly who have helped in so many ways, although space does not allow me to mention them all. In particular I thank Martin Goodey, Anne and Mike Gurr, Ren Hathway and Jo Wrigley, Wendy Hick, Francis and Carol Hicks, Johann Hicks, Lesley and David Knight, Jim Liddon, Julie Love, Amanda Martin (IOS Museum), Cyril Nicholas, Steve and Julia Ottery (and the Museum Flower Ladies), Adrian and Mandy Pearce, Penny Rodgers.

Specific help and comments on individual chapters and topics were generously given by Jon Akeroyd, J. F. Archibald, Ian Bennallick, Sarnia Butcher, Adrian Colston, Bryan Edwards, Bob Emmett, Chris Haes, Steve Hopkin, Julia MacKenzie, Rosalind Murphy, John Ounstead, Helen Parslow, John Parslow, Mark Phillips, Peter Robinson, Katherine Sawyer, Sylva Swaby, Andrew Tompsett, Stella Turk, Steve Westcott and Will Wagstaff Keith Hyatt not only read all the first draft text but found lots of useful snippets of information as only he can; Ian Beavis freely allowed use of all his material on Aculeate Hymenoptera and other groups; Jeremy Clitherow and Alison Forrester (English Nature) gave me access to many unpublished reports and other scientific information; David Mawer (IOSWT) has been a constant source of information on all aspects of natural history in the islands. The Isles of Scilly Bird & Natural History Review published by the ISBG has also been a rich source of recent information.

I must also acknowledge the team at HarperCollins, especially Richard West, who read the first draft, Helen Brocklehurst and Julia Koppitz, and above all Hugh Brazier, for many improvements to the text.

To my son Jonathan (Martin) Parslow and daughters Annette and Helen, who shared the early visits to Scilly and still love Scilly as much as I do, I dedicate this book.

CHAPTER 1 An Introduction

It’s a warm wind, the west wind, full of birds’ cries; I never hear the west wind but tears are in my eyes.

For it comes from the west lands, the old brown hills, And April’s in the west wind, and daffodils.

John Masefield, The West Wind

ALTHOUGH MASEFIELD probably did not have the Isles of Scilly in mind when he wrote those lines, they often remind me of the islands. In the early days of the year the low hills are brown with dead bracken stems and heather and there are daffodils and narcissus everywhere (Fig. 1). Seabirds wheel and call and often the climate is quite mild and balmy.

The rocks and islands that form the Isles of Scilly are located about 45 kilometres (28 miles) southwest of Land’s End. Mysterious, romantic and beautiful, they have long exercised the imagination of storytellers and historians, and legends abound that the Isles were once the lost islands of Lyonnesse or the undersea land of Atlantis. Or they may have been the islands known to the Greeks and Romans as the Cassiterides, the Tin islands, although there is little evidence of there having ever been any significant tin-mining on the islands.

The hills in Scilly are not high: most are under 45 metres, and the highest point is near Telegraph on St Mary’s, 49 metres above chart datum. The Isles of Scilly archipelago forms a roughly oval-shaped ring of islands in shallow seas of fewer than 13 metres in depth, except for the deep channels of St Mary’s Sound between St Agnes and St Mary’s, Smith Sound between St Agnes and Annet, and the deep waters towards the Western Rocks. Among the main group of islands are extensive sand flats the sea barely covers, with less than three

FIG 1. February on St Agnes, with daffodils flowering among the dead bracken. (Rosemary Parslow)

metres depth of water over much of the area at high tide, and with wide sand spits and shallows. At low water St Martin’s may be inaccessible by launch.

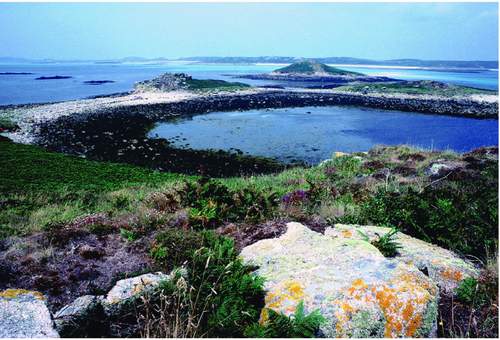

When you fly into the islands you first see the low-lying islands of the Eastern Isles looking green and brown with vegetated patches and rock (Fig. 2). Often the sand spits in the turquoise sea over the sand flats are revealed before you descend over the neat fields and cultivated land of St Mary’s to land on the airfield (Fig. 3). From the air the huge number of tiny islands and the many reefs and rocks under the water show how easily so many hundreds of ships have been wrecked in Scilly over the centuries (over 621 known wrecks have been recorded) (Larn & Larn, 1995). Even today, with depth gauges, GPS and radar, as well as more accurate charts, ships and other craft still get into trouble among the islands every year.

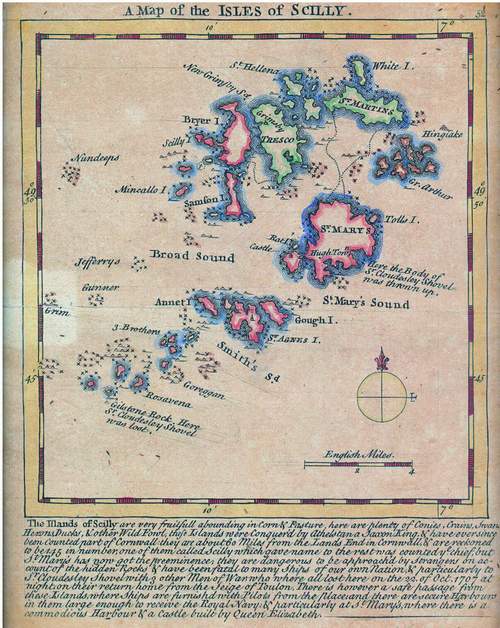

The inscription on an eighteenth-century map based on Captain Greenville Collins’ Great Britain’s Coasting Pilot survey (Fig. 4) refers to one of the most notorious Scilly shipwrecks, in addition to several other features of the islands:

The Ifands of Scilly are very fruitfull abounding in Corn & Pasture, here are plenty of Conies, Crains, Swans, Herons, Ducks, & other Wild Fowl, thefe Islands were Conquer’d by Athelstana Saxon King, & have ever since been Counted part of

FIG 2. The Eastern Isles: the view from Great Arthur towards Little Ganilly and St Martin’s. (Rosemary Parslow)

FIG 3. A patchwork of bulb fields, St Mary’s, February 2004. (Rosemary Parslow)

FIG 4. Eighteenth-century map of the Isles of Scilly, probably based on the Great Britain’s Coasting Pilot survey by Captain Greenville Collins, first published in 1693.

Cornwall: they are about 60 miles from the Lands End in Cornwall & are reckoned to be 145 in number; one of them called Scilly which gave name to the rest was counted ye chief, but St Mary’s has now got the preeminence; they are dangerous to be approach’d by strangers on account of the hidden Rocks & have been fatal to many Ships of our own Nation, & particularly to Sr. Cloudsley Shovel with 3 other Men of War who where all lost here on the 22. of Oct. 1707 at night, on their return home from the Siege of Toulon. There is however a safe passage from these Islands, where Ships are furnish’d with Pilots from the Place; and there are secure Harbours in them large enough to receive the Royal Navy: & particularly at St Mary’s, where there is a commodious Harbour & a Castle built by Queen Elizabeth.

Although there is an island called Scilly Rock off the west coast of Bryher that is reputed to have given its name to the group, this is probably not so. In the Middle Ages the name for all the islands was variously Sullia or Sullya, becoming Silli later. The current spelling as ‘Scilly’ is a more recent form to prevent confusion with the word ‘silly’ (Thomas, 1985). The islands are usually referred to as the Isles of Scilly or Scilly, never the Scilly Isles!

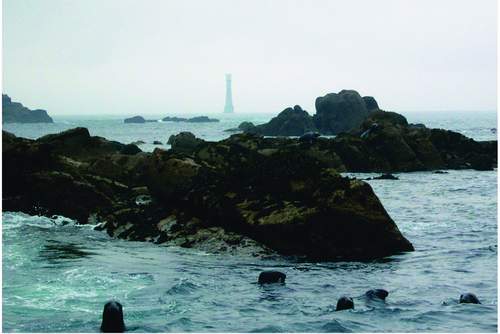

There are five islands that are now inhabited, plus some forty or so uninhabited (by people, that is – rather arrogantly we ignore the other inhabitants) and large enough to have vegetation on them, and then a further 150 or so rocks and islets. The figure cannot be definite as every stage of the tide changes one’s perspective as land is alternately exposed and hidden by the sea. From the isolated Bishop Rock with its tall lighthouse in the southwest of the group (Fig. 5) to Hanjague, east of the Eastern Isles, is 17.5 kilometres, and the archipelago

FIG 5. The Western Rocks and the Bishop Rock, the westernmost point of the Isles of Scilly, with resident grey seals. (David Mawer)

extends some 13km from north to south. The islands have a total land area of about 1,641 hectares or 16km2, more of course at low tide when more land is uncovered (Table 1). Situated on latitude 49° 56’ N and longitude 6° 18’ W, the islands are on the same latitude as Newfoundland, but the climate under the warming influence of the Gulf Stream is very different. Although the islands are part of Watsonian vice-county 1 (West Cornwall) for recording purposes, they are often treated as vice-county 1b for convenience. All the islands fall within four 10km grid squares, with most of the land being contained within just three, the fourth square being mostly water.

TABLE 1. The Isles of Scilly: areas of the principal islands. Areas are all in hectares at MHWS. (Figures from Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust)

Isles of Scilly total area at MHWS = 1,641ha

Total area at LAT (lowest astronomical tide) = 3,065ha

Number of islands (includes rocks and stacks) of any size at MHWS = 818

Number of islands at MLWS = 3,825

Number > 0.03 ha at MHWS = 203

Number > 0.09ha (so possibly with some vegetation) = 101

CLIMATE

The climate of the Isles of Scilly is characterised as oceanic, with mild wet winters, mild sunny summers, frequent strong winds and gales, and also sea fogs. A major influence on the climate is the North Atlantic Drift, an arm of the Gulf Stream. Compared with the Cornish mainland Scilly has milder winters (February mean 7.3°C) and cooler summers. The average monthly mean temperature is 11.7°C (National Meteorological Library). With most days in the year having a temperature usually above 5°C, many plants can grow in Scilly that cannot survive on the mainland. This also includes winter annuals that grow throughout winter and flower very early in spring. As many plants on the islands are frost-sensitive the occasional bad winter can cause a considerable amount of damage. Fortunately snow and frost are much less frequent than on the adjacent mainland. Snowfalls are relatively infrequent; frosts are occasional and usually neither very hard nor long-lasting.

The rare occasions when there have been more severe frosts have had a devastating effect on the vegetation, especially the ‘exotic’ plants. Winter 1987/8 was one such occasion, with almost all the evergreen Pittosporum hedges being either killed outright or cut to the ground. Hottentot fig Carpobrotus edulis is one species that can be susceptible to both frost and salt water, but as the stands are usually dense there is nearly always a piece of the plant protected enough to survive and grow again. Rainfall is low compared with Cornwall, 825mm per year on average; some of the rain clouds appear to pass over the low islands without precipitation. The islands are prone to sea fogs and this increases the general humidity, which is reflected in the rich lichen flora – also an indicator of the clean air and lack of industrial pollutants.