Полная версия

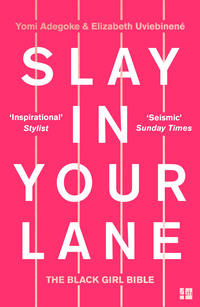

Slay In Your Lane: The Black Girl Bible

For black women, this is exacerbated by the fact that we tend only to be shown a narrow range of possibilities for ourselves, and are bombarded with the idea that there are only certain roles for certain people. Heidi understands this all too well from her research: ‘There is so little representation of you, as a young black girl, in school, so you don’t see your image in a positive way in the textbooks, in the history. A student of mine, she did her PhD on black history, and she said that when she interviewed black kids, boys and girls, and their parents, they said, “We don’t want black history to be taught in schools because it’s always about slavery and the enslaved, and then we get teased.” She said it’s the way that it’s taught that is the problem. Not that it’s taught as part of the horrors of the colonial and imperial system, no. Or how it fuelled the industrial revolution, no. It’s taught as a separate thing, which is degrading, and so the only images that you do see are in chains, being lynched or something, and you’ll never see positive images.’

One of the things we hope to achieve with Slay In Your Lane is to show young black girls that there is no limit to the roles they can carve for themselves in the world.

Malorie Blackman OBE is an award-winning children’s author who held the position of Children’s Laureate from 2013 to 2015. She believes it’s incredibly important for black children to have these visible role models. ‘When I was a child, even though I loved reading and I loved writing, it didn’t occur to me that I could be a writer because I’d never seen any black writers, and in fact, the first time I read a book by a black author was The Color Purple, and that was when I was 21 or 22. Now, that’s a ridiculous age to get to before you actually read about black characters written by a black author, and it was only reading that that led me to the black bookshop in Islington, when it was there, and that’s where all my money went. I remember in one lesson, I said to my teacher, “How come you never talk about black achievers, and scientists, and inventors?” And she looked at me smugly and said, “’Cos there aren’t any.” And, I didn’t know any better, I had never been taught about them, so I felt there was a huge gap in my knowledge about my own history: never been taught it, never come across any books about my own history, so when I found a black bookshop, it was non-fiction books, it was mostly African-American writers, but I devoured them.’

Sharing Malorie’s views on the necessity of visible role models, Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock has relentlessly pursued a schedule of school visits alongside her academic work: ‘This is quite a multi-pronged challenge. My goal is to get more, especially black, girls into STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths], because it’s the same across the board really, there are internal challenges and external challenges. Internally, I think many girls don’t consider STEM, especially black girls, but it’s the same with black boys really. When they see role models or black role models they see footballers, they see singers, they see people who are doing brilliant jobs, but they don’t see many scientists. They see maybe a few more medical doctors now, but sort of within a limited catchment. And so it’s trying to expose them to as many role models as possible in as many different disciplines as possible. It’s funny, when I go to schools, I talk about science and I talk about space but I do not necessarily want them to become space scientists like me, I just want them to know that they have amazing opportunities and there are amazing careers out there that might be suited to them. Some of the children might be great as space scientists, but some of them might want to do something totally different. But it’s showing them that as a black girl in a school, the sky’s the limit, you can do anything you set your mind to, but you’ve got to actually know what the opportunities are. It’s trying to get them exposure to opportunities. I think it doesn’t happen quite so often, but I think in some places they still try to limit people’s expectations. And that’s especially true for girls and I think especially true for black girls. So it’s sort of like the situation I was in – “Oh Maggie, don’t aim too high” – almost know your place in life, and I find that quite frustrating. So I like to show my story as an example, you know, I started off exactly where you are sitting and now I’m up here and I’m doing really exciting things and I love my work. So it’s showing them that there are amazing things that they can do, that they have the potential, and the thing is to believe in themselves. So it’s trying to tackle away the external barriers and the internal barriers.’

And positive changes are happening. Natasha Codiroli finds that female students of mixed ethnicity and Black Caribbean origin are more likely to study STEM A-levels than white female students.11 Indeed, black girls are the only ethnic group that outnumbers their male peers in STEM A-levels.12 STEM is important in driving innovation and is the fastest-growing sector in the UK. There’s never been a better time to encourage young girls into this industry. Role models like Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock understand the need to be visible to school children, and outreach projects are becoming increasingly important in encouraging more black women into all sorts of industries.

Malorie agrees: ‘So, as far as representation is concerned, I think it is absolutely vital, because if I hadn’t read those books, it still wouldn’t be in my head that I could be a writer because I’d never seen any! I remember, for example, when I first started writing, and I wrote a book called Whizziwig, and it was on CITV (Children’s ITV) for a while. I remember going into a school – and this was really instructive to me in terms of representation, because I went into a school in Wandsworth – and I’d say about a third of the pupils were black, or children of colour, and two-thirds were white. I remember that I was talking about Whizziwig, and the idea, and it was on TV and a number of them had watched it, and a black boy put his hand up and he said, “Excuse me, so, Whizziwig was on the television and then you wrote it?” And I said, “No, I wrote it, and then it was on the television.” He said, “But, it was someone else who did it, and then you did it?” And I said, “No, it was my idea and then I wrote the book and then it was made into a TV programme.” And he asked me about five or six questions, all on the same theme, and I was like, “No, I wrote it.” I know exactly what you’re thinking, and I just thought, I loved it, because I was sitting with a sort of smile inside, thinking, I want you to look at me and think, hell, she ain’t all that, so if she can do it, I can do it! And that’s what it was, “You did it? You wrote it?” And I thought, that’s exactly the point! And so I just love that, and that’s why, especially to begin with, sometimes it was two or three school visits a week, and I got out there, oh my God, and I was up and down the country and I made sure I got out there to show, not just children of colour, but all children, that writers can be diverse, that I was a writer. Here I was as a black woman and a writer!’

Similarly, in 2017, Yomi and I were invited by London’s Southbank to mentor young girls between the ages of 11 and 16 for the International Day of the Girl festival. It took me back to my school years and the fear of not knowing what was ahead of me past GCSE results day. Unlike when I was growing up, these girls seemed more confident about what they wanted to do, and asked us interesting questions about our careers and why we made the decisions we did. They didn’t seem lost like I did at their age and that filled me with great hope that things seem to be slowly but surely improving.

In summary, we’ve spoken about the need for an increase in black teachers, the need to tackle the bias held in some pockets of teaching staff through training and accountability, and that parents also need to better understand the school system so they can best support their children in the face of these obstacles. The general feeling of being lost that I experienced throughout school, and especially over that summer as I waited for my GCSEs, came from a lack of confidence in myself that originated in the school system. Changes are slowly happening, but we need to do more to raise the self-esteem of young black girls, so that they know that the sky is indeed the limit, and to actively give them the tools to help them realise their ambitions.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.