Полная версия

China

In addition, recent studies have detected many of the devices noticed in earlier classics like the Shijing and Confucius’s Analects – an obsession with names and their ‘rectification’, meanings implied by allusion and the ‘correlation’ of apparently unrelated materials, and that emphasis on faithful transmission rather than innovation. But perhaps the most intriguing insight is that which interprets the Shiji as being a rival to the First Emperor’s tomb in that it too represents a model, or microcosm, of the world as then known. Here, albeit in prose, the heavens and their constellations are also represented, and likewise the empire’s rivers and waterways, its geographical divisions and its clustered high officials. As Grant Hardy puts it:

The First Emperor’s tomb was an image of the world created and maintained by bronze – the force of arms – whereas Sima Qian’s Shiji offered an alternative depiction of the world, inscribed on bamboo slips and regulated by scholarship and morality…If Sima’s creation could not match the First Emperor’s in political power, it far surpassed it in influence, and eventually the famous mausoleum was known and understood by the place it held in Sima Qian’s all encompassing bamboo-world.2

On the other hand if, when the mausoleum is opened, its furnishings are found to exceed or contradict Sima’s description, it may be the First Emperor who has the last laugh. Already the ‘terracotta army’ has added an unsuspected military dimension. Further finds – imagine the consternation if they include books – could confound not only the Grand Historian but a hundred generations of subsequent historians.

If the First Emperor’s innermost coffin is found intact, it may even be possible to discover what he died of. But until then ‘the bamboo record’ must suffice. In 210 BC the First Emperor was still in his forties and apparently fit enough to undertake another tour of his domains. Only days before his collapse he was out shooting sea monsters on the Shandong shore. The suggestion that he was a victim of poisoning therefore seems plausible. But if this was the case, the dose was probably self-administered; for in the potions prepared for him by the experts in immortality the vital ingredient was cinnabar. A mineral rarity, cinnabar came largely from Sichuan and was used as a pigment, most notably to impart a ruddy shade of vermilion to the ink reserved for emperors. As a crystalline form of mercuric sulphide, it is also toxic, and when ingested in quantity, fatal. Gulping down the draughts that promised eternal life, the First Emperor may have been inviting a rather sudden death.

According to Sima Qian, at the first hint of indisposition Meng Yi, the chief minister and brother of the wall-building Meng Tian, had been sent post-haste from Shandong to organise ‘sacrifices to the mountains and rivers’, presumably for the emperor’s recovery. That left the imperial cavalcade in the charge of Li Si, the book-burning chancellor, assisted by Zhao Gao, a eunuch who held the important post of chief of the imperial carriages, plus Prince Huhai, the emperor’s youngest son. When the emperor expired just days after Meng Yi’s departure, Li Si proved uncharacteristically indecisive. Instead it was Zhao Gao who took the initiative. The eunuch had a score to settle with the Meng brothers; Prince Huhai, a callow youth with no redeeming qualities other than his parentage, was conveniently to hand; and Li Si, who must by now have been in his sixties, was rather easily talked into manipulating the succession.

The dead emperor’s written testament appointing another son as his heir was accordingly suppressed. So too was report of the death itself, for it was vital that the plotters reach Xianyang and secure the reins of power before the news of the emperor’s demise encouraged others to thwart them. The cavalcade therefore rumbled on towards the capital as if nothing had happened. Meals for its reclusive principal were delivered to his carriage as usual, while a wagon of fish was positioned near by to counteract the stench of rotting emperor.

On regaining the capital, the plotters swung into action. Prince Huhai was proclaimed the emperor’s designated heir and installed as the Qin Second Emperor. The First Emperor’s preferred heir was then charged with treason and, in forged orders from his father, commanded to commit suicide – which, being a truly filial son, he did. Then the Meng brothers were censured for opposing these arrangements and detained until such time as Meng Yi could be executed and Meng Tian obliged to take poison.

These events were accompanied by a reign of terror that, as described by Sima Qian, must have made the dead emperor’s heavy-handed administration seem almost benign. ‘Make the laws sterner and the penalties more severe,’ urged Zhao Gao. ‘See that those charged with a crime implicate others and that punishments extend to the families of the criminals. Wipe out the chief ministers and sow dissension among their kin.’ With the scheming eunuch acting as grand inquisitor, twelve princes and ten princesses were dismembered in the Xianyang marketplace. Those implicated with them together with their ‘three degrees of relatives’ – traditionally parents, siblings and offspring – suffered a similar fate but were ‘too numerous even to be counted’. New laws and harsher punishments were promulgated. Taxes and levies were increased, and yet more forced labour was marched off to work and die on still-incomplete projects such as the Opang Palace and the northern frontier’s walls. ‘Each man began to fear for his own safety,’ says Sima Qian, ‘and those who longed to revolt were many.’3

Rebellion in fact broke out within six months of the First Emperor’s death. It had already spread through the eastern commanderies when in the following year (209 BC) Li Si became the next victim of note. Shunned by the witless new emperor, ‘China’s First Unifier’ was duped by Zhao Gao, tortured until he confessed to treason, and then condemned to undergo ‘the five penalties’. These consisted of tattooing, amputation of ears, nose, fingers and feet, flogging, beheading and public exposure of the severed head. For good measure, Li Si’s torso was also cut in two at the waist. Few destroyers of books can themselves have been so comprehensively shredded.4

Meanwhile Zhao Gao had begun gunning for his imperial puppet. In anticipation of the fable about ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, His Majesty was invited to accept the gift of a horse that was in fact a deer. When he made some remark to that effect, Zhao Gao and other attendants corrected him: all agreed it was a horse, and they further pretended concern that His Majesty might be labouring under a delusionary condition. The Grand Diviner then confirmed that there had of late been some liturgical shortcomings in the imperial performance of the ancestral rites. The Second Emperor was advised to withdraw from public life to fast and purify himself.

While thus secluded, a hostile force invaded his place of retreat. Zhao Gao declared it to be the advance guard of a rebel army (it was of course nothing of the sort, just his own carefully drilled cohorts) and advised the young emperor to pre-empt capture and execution by taking poison. After further prompting and not a little threatening, the emperor obliged. Zhao Gao himself then seized the imperial seals.

This, however, was too much for the other officials and much too much for Heaven, which made its feelings felt with three hefty earth tremors. Zhao Gao therefore turned to a grandson of the First Emperor, who, though reluctant to accept the throne, did the next best thing: he had Zhao Gao murdered. By now it was 207 BC, only three years since the First Emperor’s death but long enough for his entire empire to be up in arms. As an inheritance it was not worth the risk of acceptance; in fact the grandson may already have been in touch with the rebels. Within three months they would be entering Xianyang itself.5

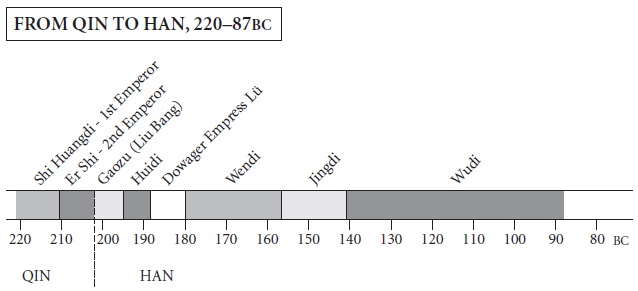

PAWN TO KING

‘Rebellion’ would seem a misnomer for the groundswell of protest that greeted the Second Emperor’s excesses. There was an element of restoration about the uprising, of reinstating the old ‘warring states’, plus a strong sense of righteous obligation in overthrowing an imperial house that had so patently forfeited Heaven’s favour. To be fair, it is doubtful whether Qin ever really laid claim to such a thing. The First Emperor’s inscriptions scarcely mention Heaven, let alone the Mandate; and if they were drafted by such a rabid legalist as Li Si, this is hardly surprising. But in Confucian terms, legitimacy now lay firmly with the anti-Qin forces and would continue to do so throughout the next seven years of civil war.

Sima Qian deals with this confused period exhaustively, recounting the marches and counter-marches, the engagements and intrigues in remorseless detail, but always from the perspective of the contending ‘rebel’ camps, not of the blood-spattered Qin court at Xianyang. Larger-than-life personalities emerge from the mêlée and hint at major issues. What might otherwise have seemed like a brief and belated throwback to the ‘Warring States’ period is portrayed as a seminal moment, a historical watershed and a Grand Historian’s grand opportunity. China’s political future was being decided and its official ideology forged. The Han empire that resulted would enshrine features of Chinese culture that would be revered ever after and lend compelling substance to the idea of a continuous civilisation.

Of all the issues involved in the power struggle – territorial, dynastic, philosophical and fiscal – perhaps the most surprising was social, in that dissent swelled from the lowest ranks of society. Resistance to Qin rule proved to be not just popular but populist. In his determination to mobilise the manpower of the empire, the First Emperor had established a direct relationship between the centralised government and the localised governed. Wrenched from mass oblivion, the black-haired commoners had been dragooned into participating in the historical process. Millions had been uprooted to fight, labour or colonise on the empire’s behalf. Millions more had been obliged to support this effort through heavy taxation and collective liability backed by ferocious penalties. Their woes were shared and their fears real. While nationalists would later applaud the First Emperor’s efforts at unification, and while Maoists would approve his autocratic efforts in mass mobilisation, orthodox Marxists would be more gratified by the anti-Qin response and its early evidence of peasant revolt and class consciousness.

The first challenge came from a ploughman of the erstwhile state of Chu, who was called Chen She. Ordered to the frontier with a gang of conscripts in 209 BC, Chen She calculated that the heavy rain was making it impossible for them to reach their destination on schedule and that since they would therefore be treated as deserters, they might as well as desert. A colleague agreed and, by dint of some supernatural trickery, convinced the other conscripts to join them. The cry of ‘Great Chu shall rise again’ was first heard coming from a spookily lit shrine at dead of night; it was followed by the refrain ‘Chen She shall be a king’, the very words that one of the conscripts had just found written in imperial cinnabar on a piece of silk miraculously preserved inside the belly of his fish supper. As portents went, these were both explicit and imperative. The conscript gang was transformed into a band of rebels, quickly snowballed into an avenging army, and then, as others followed Chen She’s example, became the vanguard of a great anti-Qin coalition. Chen She resurrected the ancient state of Chu and declared himself its king. Other pretenders followed suit north of the Yellow River in erstwhile Yan, Zhao and Wei.6

Sima Qian would dub Chen She ‘the Melancholy King’. Accustomed to history’s neglect of the common man, the Grand Historian was intrigued how someone ‘born in a humble hut with tiny windows and a wattle door, a day labourer in the fields and a garrison conscript, whose abilities could not match even the average’, could yet ‘step from the ranks of the common soldiery, rise from the paths of the fields and lead a band of a few hundred poor and weary soldiers in revolt against…a great kingdom that for a hundred years [i.e. since Qin’s acquisition of Sichuan] had made the ancient eight provinces pay homage at its court.’ The only explanation had to be that offered by Confucians: Qin had failed to rule with righteousness and humanity and had failed to realise that the qualities required of a ruler were not those of a conqueror. Thus Chen She had only to ride a wave of righteous protest. But when he too proved a neglectful ruler, he was himself engulfed by this wave, in fact murdered within the year by one of his own retainers. Melancholy indeed, mused the Grand Historian.7

A new breed of leader now emerged, the foremost example being Xiang Yu. Another native of Chu but an aristocrat rather than a commoner, descended from a long line of Chu generals, Xiang Yu towered above his contemporaries in both physique and accomplishment. He was foul of temper but fearless in battle, and his men worshipped him. Though historians nurtured in the literary and bureaucratic tradition found nothing remotely romantic in battlefield antics, Xiang Yu would prove an exception. Sima Qian called him arrogant, deceitful and ungrateful, yet could neither disguise his admiration nor resist the sort of detail calculated to enhance a heroic reputation. Xiang Yu strides from the pages of the Shiji like no other warrior; and it is testimony to the Shiji’s influence that he is still sometimes hailed as the most accomplished general in the whole of Chinese history.

Scenting a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, other leaders emerged from the masses more like Chen She. Liu Bang of Pei, a district in the north of what had been (and was again) Chu, had also fallen foul of the Qin authorities and taken to brigandage. But while the melancholic Chen She had had to contrive his own portents, and while the mighty Xiang Yu was well enough endowed to manage without them, Heaven of its own volition showered the young Liu Bang with auspicious signs and lucky encounters. Dragons – of all animals the most closely associated with power and celestial favour – featured in many of these manifestations. His mother had conceived him by a dragon, another hovered over him when he slept, and his well-whiskered features were sufficiently dragon-like to excite physiognomists (they foretold your future from your face), one of whom, a certain Lü, was so impressed that he gave him his daughter in marriage. Thus does the Grand Historian waste no time in flagging the future founder of the Han dynasty and his influential consort. Readers are not to be misled by Liu Bang’s limited education, his boorish behaviour and indifferent military record. Heaven’s favour would more than compensate.

Following the death of Chen She, it was the inspirational Xiang Yu who quickly made a name for himself as a commander. He then took over the reconstituted kingdom of Chu, first as the power behind the puppet throne, then as king and eventually as ba (‘hegemon’ or ‘protector’) over a cluster of satellite states. The dragon-blest Liu Bang of Pei, his gang having grown to an army, allied himself with Xiang Yu and his Chu forces. In 207 BC, the year in which the Second Emperor committed suicide and Zhao Gao was murdered, the armies of the now commander-in-chief Xiang Yu inflicted a succession of heavy defeats on the Qin forces, driving them back to the hill passes that guarded the Qin stronghold along the Wei River. ‘The war-cry of Chu shook the heavens, and the men of the other armies all trembled with fear,’ says Sima Qian.8

Meanwhile Liu Bang of Pei led his men west by way of the Han valley and then north towards Qin. Finding the passes from this direction less well defended, he opened contact with the Qin court at Xianyang, learned of the fall of the Second Emperor, and received some encouragement from the First Emperor’s grandson, who was now the would-be (or more precisely ‘would-rather-not-be’) ‘Third Emperor’. Without consulting his allies, Liu Bang then marched on the capital and took it.

As his superior commander, Xiang Yu was furious. He too thrust towards Xianyang and, threatening to exterminate both the enemy and his ally, encamped his 400,000 men within a day’s march of Liu Bang’s 100,000. It was not just a question of Liu Bang’s insubordination. Rumours of his having made a deal with Xianyang were rife, and they seemed to be borne out by the extraordinary clemency Liu Bang had shown towards Qin’s people and their would-rather-not-be emperor. Such restraint suggested that Liu Bang was both currying favour in Qin and cultivating a reputation for superior virtue, as sure a sign of imperial ambitions as the celestial dragons and tigers that were reported circling over his camp.

To fend off a clash of Qin’s joint conquerors, a reconciliation was attempted by go-betweens. Liu Bang reported to Xiang Yu in person; but even as the liquor flowed and loyalties were reaffirmed, weapons were being fingered by their jumpy retainers. Pretending a weak bladder, Liu Bang excused himself, left the audience tent and failed to return. On learning that he had in fact been smuggled back to his own army in safety, Xiang Yu fell into a towering rage. (Sima Qian has him fuming rather often.) Such wrath could be assuaged only by turning on Xianyang, massacring its inhabitants, torching its palaces and archives (so probably burning more books than Li Si), murdering the now would-definitely-not-be ‘Third Emperor’, and in one of the Shiji’s several versions of this grisly episode, ‘desecrating the grave of the First Emperor’ – which could account for the shattered state of ‘the terracotta army’.

This action of Xiang Yu’s was particularly reprehensible in that the city had already surrendered, albeit to his rival; and Xiang Yu now compounded his mistake with a string of others. Instead of establishing himself within the natural stronghold that was the state of Qin, he headed back east; trouble was brewing in Shandong, his men were homesick, and Chu’s new capital at Pengcheng awaited its hero. In his absence, the state of Qin was divided into four lesser kingdoms, with Liu Bang being fobbed off with its outlying commanderies in Ba and Shu (Sichuan) plus the neighbouring upper Han valley. Xiang Yu seems to have assumed that, since Sichuan was notoriously a place of exile, relegating his rival to this far-flung region beyond the Qinling range would keep him out of mischief. Liu Bang, or ‘the King of Han’ as he was now to be styled, saw it more as a lucky escape and a safe refuge. To make doubly sure that he was not pursued, he dismantled the carpentry of Stone Cattle Road and other mountain trails behind him.

From this 206 BC appointment of Liu Bang of Pei as king of Han, the Han dynasty would date its foundation and take its name; but it would be another four years of strife and appalling bloodshed before the Han king became the Han emperor. For no sooner had Xiang Yu marched east than Liu Bang marched north again, replacing the mountain road and retaking the Qin heartland.

The titanic struggle that now unfolded would achieve epic status. Thanks to Sima Qian, the protagonists would win such fame that references to the spirit of Xiang Yu or the stamina of Liu Bang would come to rate as conversational clichés. To this day, Chinese chessboards often indicate that one end is for ‘Han’ rather than ‘black’ and the other for ‘Chu’ rather than ‘white’.9 The rules of combat, such as they were, were mutually understood; move by move the game must progress until a king was toppled. But the odds were evenly stacked, and though fortunes would fluctuate, the outcome remained uncertain till the bitter end.

Liu Bang made the opening move. With a secure base in Qin and with the unlimited resources of Sichuan to draw on, he was in the same enviable position as the Qin kings of the ‘Warring States’ period. At the head of an army that had suddenly grown to a no doubt exaggerated 560,000 men, he swept east and took the Chu capital of Pengcheng. Meanwhile Xiang Yu, whose kingdom was more vulnerable to attack from the rear, was quashing opposition far to the east in Shandong. Greeting the news of Liu Bang’s onslaught with his customary outburst, Xiang Yu headed to the rescue. Despite a march of several hundred kilometres and only 30,000 men, he drove back the enemy, reclaimed Pengcheng and won two resounding victories – such was his undoubted genius as a field commander.

Liu Bang should have been captured at the second Pengcheng battle. But surrounded on all sides and with no hope of relief, he was saved by a dust storm. Day turned to night and he escaped in the confusion; Heaven had not forgotten him. His family were taken prisoner and his great army virtually annihilated, but he fought on. Twice more he was surrounded and twice more escaped. A lull while Xiang Yu marched off to quell more unrest on his eastern seaboard allowed Liu Bang to recoup his strength. Provisions and men reached him from Sichuan and Qin down the Wei and Yellow rivers; other hastily recruited forces were sent to stir up trouble behind the Chu lines and to intercept supplies.

By the time Xiang Yu returned to the front in 203 BC, a military stalemate had set in. To break it, Xiang Yu first threatened to kill Liu Bang’s captive father, then offered to settle matters in personal combat with Liu Bang himself. Liu Bang failed to rise to either challenge. Time, as well as Heaven, was now on Liu Bang of Han’s side. While his resources were being constantly replenished from Sichuan and Qin, Xiang Yu’s troops were tiring, their supplies failing and their strength being sapped by constant trouble from Chu’s supposedly subordinate states. With Xiang Yu away putting down yet another such revolt, Liu Bang experienced a rare taste of victory. It was short-lived. Again Xiang Yu came dashing to the rescue and again Liu Bang withdrew rather than risk battle with an apparently invincible foe.

Both sides repeatedly accused one another of treachery; there was in fact little to choose between them in this respect. Even Sima Qian, a Han subject who had necessarily to uphold the reputation of the Han founder, had no intention of thereby damning the great Xiang Yu of Chu. Mean, violent, vain and distrustful the Chu king undoubtedly was, declared the Grand Historian, while all the time depicting a dazzling hero for whom nothing less than a climax of high tragedy would suffice, plus – as he warmed to his task – some of the purplest passages in the whole of the Shiji.

In late 203 BC the mutual insults gave way to ceasefire overtures. Both rulers agreed to withdraw; Xiang Yu surrendered Liu Bang’s family; and the empire was tentatively divided along the north–south line of a canal between the Huai and Yellow rivers. Xiang Yu’s Chu retained all to the east, Liu Bang’s Han all to the west. A relieved Xiang Yu at last pulled back. But an encouraged Liu Bang went after him, harrying the Chu van and picking off stragglers. What should have been a victorious homecoming for Xiang Yu’s men began to assume the appearance of an undisciplined rout. Liu Bang pressed ever harder and his forces grew by the day. Lukewarm supporters flocked to his standard on the promise of fiefs that he might now actually be able to deliver. So did deserters from the disillusioned ranks of the enemy.

The last great battle was fought at a place called Gaixia in northern Anhui. Outnumbered three to one, Xiang Yu’s forces were finally overwhelmed and he himself surrounded, ‘his soldiers being now few and supplies exhausted’. That night Xiang Yu could not sleep, reports Sima Qian. From the Han encampments came the sound of music. They were singing the songs of Chu. Was it possible, asked Xiang Yu, that so many men of Chu had already defected?

Then he rose in the night and drank within the curtains of his tent. With him were the beautiful Lady Yü, who then enjoyed his favour and went everywhere with him, and his famous steed ‘Dapple’, which he always rode. Xiang Yu, now filled with passionate sorrow, began to sing sadly. [His song was of how the times were against him, of Dapple’s exhaustion and of what would become of ‘Yü, my Yü’.] He sang the song several times and Lady Yü joined with him. Tears streamed down his face, while all those about him wept and were unable to lift their eyes from the ground. Then he mounted his horse and with 800 brave riders beneath his banner, rode into the night, broke through the encirclement to the south, and galloped away.10