Полная версия

China

But unlike zhongguo’s flexible equation with ‘Central States’, ‘Middle Kingdom’ and then ‘Central Country’, the etymology of ‘Qin = China’ is far from straightforward. Sanskrit’s adoption of the ‘sin’/‘cin’ root seems to predate the rise of Qin; it could, in that case, derive from Jin (pronounced ‘zhin’), the hegemonic state headed by Chonger in the seventh century BC. Much later, the Graeco-Roman world in fact knew two Chinas: Sinai/Thinai and Seres (or Serica), both of which exported silk but were not thought to be the same place. Medieval Europe then added yet another, Cathay. This was the country that Marco Polo claimed to have visited. Polo seldom mentions anywhere called ‘Chin’ (or ‘China’) and then only as a possible alternative name for ‘Manzi’, which was the southern coastal region.20 In this restricted sense ‘Chin’/‘China’ was used by Muslim and then Portuguese traders, but it figured little in English until porcelain from this ‘Chin’ began gracing Elizabethan dinner tables. Shakespeare caught the mood in Measure for Measure with mention of stewed prunes being served in threepenny bowls and ‘not China dishes’.21 After long gestation, china (as porcelain) was lending currency to China (as place) – just as in Roman times seres (the Latin for ‘silk’) had led to the land itself being called ‘Seres’. Ultimately, then, it was contemporary crockery from the south of the country, not an ancient dynasty from the north, which secured the name of ‘China’ in everyday English parlance and led, by extension, to the term being applied to the whole empire.

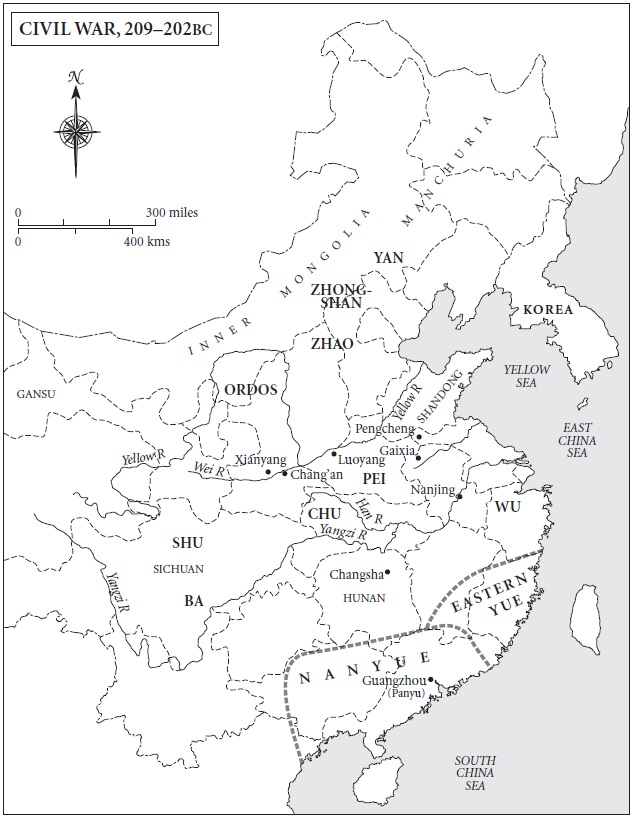

Appropriately enough, Qin was acquainted with this later, southern, ‘Chin’. In the wake of his victory over Chu (including Wu and Yue) the First Emperor extended his conquests deep into the extreme south of the country. They seem to have embraced Guangdong province and parts of Guangxi and Fujian (which together formed Marco Polo’s ‘Chin’), plus on paper at any rate what is now northern Vietnam. But uncertainty surrounds not only the extent of these acquisitions but also their timing. If, as the Shiji has it, Qin’s successful southern campaign was in 214 BC, this was only four years before the First Emperor’s untimely death and the rapid disintegration of his empire. Three new commanderies are said to have been established in the south, but since all would have to be reconquered by the Han dynasty, it must be doubtful whether Qin’s control was fully effective. Whatever its extent, the First Emperor’s southern dominion was fleeting.

As in Sichuan, though, it was notable for the cutting of an important canal. This linked a southern tributary of the Yangzi to a northern tributary of the West River, which itself debouches into the estuary of the Pearl River near Hong Kong. Designed in 219 BC to facilitate a southern advance and to provide an inland waterway through Hunan to Guangzhou (Canton), the canal would be much realigned but, like Li Bing’s waterworks, still exists. In the same year, the emperor himself reached the southernmost point of his imperial travels when he turned back somewhere just short of the proposed canal in the vicinity of Changsha. At the time the hill country to the south had not yet been secured, which should have been a good enough reason for heading north again. But the Shiji offers a different explanation, indeed one that seems designed to reveal an imperial trait which was of growing concern to ministers such as Li Si and to the whole Qin court.

Apparently the emperor was much drawn to hilltops. His inscribed stelae were usually positioned on them and he liked to climb them in person. But on an eminence near Changsha his progress was halted by what sounds like a tornado. Taking this as a personal affront, he excused the wind but blamed the hill, ordering it to be stripped of trees and painted red. Three thousand convicts were put to work immediately. Since ‘red was the colour worn by condemned criminals’22 and clear-felling the nearest thing to limb-by-limb amputation, it is evident that the hill was being punished for lèse-majesté. Delusions of more than mere grandeur were afflicting the emperor: a sense of transcendence had overcome him; ‘all under Heaven’ was his, and that included natural features. When some 2,200 years later Comrade Mao’s Long Marchers sang songs about ‘painting the countryside red’, they may not have been aware of this ominous precedent.

More significant, because it resulted in the construction of the so-called Great Wall, was the empire’s extension northwards. Sima Qian’s Shiji continues to be vague about the geography and chronology, but it seems that the First Emperor’s conquests extended right along the northern perimeter of the erstwhile ‘warring states’ and that these conquests were undertaken continuously throughout his eleven years as emperor (221–210 BC). As in Sichuan, colonists were speedily dispatched to the newly conquered territories; and frequent mention of these deployments provides a few clues as to the advance. So does the alignment, insofar as it can be established, of the Qin wall, part of which was much farther north than most of its successors. On this basis, the First Emperor’s forces look to have mounted a three-pronged advance, pushing north of west to Lanzhou in Gansu province, north of east to the edge of the Korean peninsula, and due north across the Ordos, an undulating desert wilderness within the Yellow River’s great northern loop, towards Mongolia.

The last advance, that due north across the Ordos, is the only one of which Sima Qian has much to say – and most of that in the course of a biographical note on Meng Tian, the Qin general responsible. Meng Tian was sent north with either 100,000 men or 300,000 men, probably in 221 BC, to disperse the Rong and Di peoples and take control of the Ordos. Once established there, he set about building walls. At a time when in Europe Hannibal was overcoming the natural frontier that was the Alps, Meng Tian determined to construct an artificial frontier. Its line reportedly covered a distance of 10,000 li (c. 5,000 kilometres – 3,000 miles) from Lintao (near Lanzhou) to Liaodong (east of Beijing); and initially it ran north across Ningxia province until, on reaching the Yellow River, it followed round that river’s great northern bend. Thereafter Sima Qian says nothing about its alignment; nor does he anywhere mention its purpose. He did, though, visit the scene of Meng Tian’s labours, albeit a century later. On site he seems to have been as much impressed by the 850 kilometres (530 miles) of road that Meng Tian had constructed up through the badlands of the Ordos as he was by the wall itself.

I have travelled to the northern border and returned by the direct road. As I went along I saw the outposts of the long [i.e. Great] wall which Meng Tian constructed for the Qin. He cut through the mountains and filled up the valleys, opening up the direct road. Truly he made free with the strength of the common people.23

From this it would seem that Meng Tian’s ‘Great Road’ involved more engineering than his ‘Great Wall’. The former is said to have been ‘cut through the arteries of the earth’, while the latter ‘followed the contours of the land…twisting and turning’ and ‘used the mountains as defence’ and ‘their defiles as frontier posts’.24 If Sima Qian’s 10,000 li are to be taken literally, the wall was certainly longer than the road. On the other hand it is generally accepted that Meng did not start his wall from scratch. Wall-building, both as a demonstration of exclusive sovereignty and as a defensive precaution, had been practised by the ‘warring states’ for at least a century. In places Meng Tian had merely to repair these existing stretches and connect them up.25

The term used in Chinese literature for Meng Tian’s wall, as for the ‘Great Wall’ of later fame, is changcheng, literally meaning ‘long wall’ or, as with zhongguo (‘Central States’/‘Middle Kingdom’), ‘long walls’. Cities, palaces and even villages might be surrounded by changcheng. Thus according to another interpretation, Meng Tian’s wall was not in fact a continuous construction but a succession of the ‘outposts’ observed by Sima Qian, each surrounded by its own changcheng.26 This would certainly help to explain why Qin’s changcheng receives so little mention in later history and also why it was (or they were) apparently so ineffective as a defensive rampart. If the textual context provides a clue, the section north of the Ordos was more offensive than defensive. As the culmination of a major advance and as accommodation for a permanent garrison in what had previously been Rong and Di country, the wall was (or the walls were) meant to consolidate Qin aggression rather than forestall non-Qin incursion.

Needless to say, walls, outposts, watchtowers and whatever else may have been involved were constructed of hangtu. Layers of brushwood were sometimes incorporated into the tamped-down earth, but dressed stonework like that of the sixteenth-to-seventeenth-century Ming wall was not even contemplated. Though hangtu structures last long underground, above ground they are no match for the sandstorms, extreme frosts and occasional floods of twenty centuries. Archaeologists have identified only a few stretches of Qin wall, mostly in Gansu. Yet screeds have been written about the enterprise, and some startling statistics have been deduced as to the millions of men (they served in rotation) required to shift the trillions of tons of earth necessary for 10,000 li of chariot-width wall. The loss of life is reputed to have been horrific, although whether it resulted from the climate and conditions of service on the northern frontier, from the ancillary roadworks as implied by Sima Qian, or specifically from wall-building is not clear. Walls certainly got a bad name; so did Meng Tian and the First Emperor as those responsible for the most notorious example. But of late, scholarship has been chary of such deductions. It is more inclined to demolish the whole concept of a ‘Great Wall’ and to diminish the scale and significance of Qin’s pioneering effort.

This is in marked contrast to the indulgent treatment now afforded to Qin’s other extravaganzas. Stone Cattle Road, Li Bing’s irrigation works, a similar scheme on the Wei River, the Hunan canal and Meng Tian’s road have all been archaeologically authenticated. Other Qin highways have been charted, their combined length coming to something well in excess of Gibbon’s estimate for the entire road network of the Roman Empire. But until recently the colossal dimensions of the emperor’s new Opang (Epang, Ebang) palace (675 by 112 metres – 740 by 120 yards), the labour force required to excavate his tomb (700,000 men) and the almost incredible features ascribed to that lost mausoleum had occasioned only suspicion. Then in 1974 came the discovery of ‘the terracotta army’. The ‘grave’ doubts evaporated. An emperor who could join his ancestors at the head of an entire life-size army was capable of anything.

The dimensions of the Opang palace, though probably exaggerated, no longer seem quite so excessive; the scale of the imperial tomb, its location in Xianyang having finally been discovered, prompts excited speculation; and more generally the First Emperor’s alleged eccentricities are no longer airily dismissed as the self-serving exaggerations of later historians in thrall to a different dynasty and an adverse historiography. The emperor’s devotion to the theory of the Five Phases/Elements – and water in particular – seems less far-fetched; and Sima Qian’s account of the various imperial peregrinations, including the mountain encounter at Changsha, can more readily be taken at their face value.

Although the First Emperor seems never to have led his forces in battle – few emperors would – he made five extensive tours. The Zhou kings had occasionally done the rounds of their feudatories, and future emperors, especially the Qing Kangxi and Qianlong emperors, would make the grand tour a centrepiece of imperial ceremonial. It is assumed that, like them, the First Emperor travelled to see and be seen, to exercise political oversight and be observed performing ritual ceremonies. No doubt troops were inspected and local officials interrogated; certainly orders were issued for the settlement of new colonies and the construction of new public works. But to what extent the emperor actually engaged with his subjects on these occasions is uncertain.

According to Sima Qian, he was often rather particular about not being seen. In 219 BC, on a first visit to Mount Tai in Shandong, the most sacred of summits, he completed the ascent alone and performed whatever rites he deemed appropriate in secret and without any record being made of them. Seven years later, on the advice of a man who was pandering to his hopes of longevity, he furnished each of his palaces with what might be required in the way of entertainment and female company, and then linked these establishments with covered ways and walled corridors. His whereabouts were thereafter to be kept a closely guarded secret whose revelation was punishable by death. A couple of bungled assassination attempts may have made him paranoid; no less plausibly he was embarking on what, for one who was already master of ‘All-under-Heaven’, was the ultimate challenge: mastering mortality. For just as climbing hills excited his sense of commanding the physical world, so removing himself from public sight was supposed a step towards transcending the passage of time.

Death, says Sima Qian, was made a taboo subject, with any talk of it being punishable by the same – now unmentionable – fate. Sorcerers, magicians and miracle-men with a working knowledge of eternity were summoned for examination. No expense was spared in obtaining the life-prolonging elixirs they recommended – but which may in fact have poisoned him – nor in countering the portents of mortality that surfaced with disconcerting frequency. More encouraging news came from Shandong province, long a repository of the arcane as well as the orthodox. It concerned a mountainous archipelago in the Yellow Sea where immortality, or a means of obtaining it, was reputed commonplace. The emperor determined to investigate.

Four of his five grand tours included a sojourn by the sea, whose immensity must have impressed someone from landlocked Qin and especially one whose rule depended on ‘the power of water’. On the second tour, in 219 BC, he dispatched an expedition to discover the immortals in their so-called Islands of Paradise. Since the chosen explorers consisted of ‘several hundred boys and girls’, he seems to have anticipated the voyage being a long one. He was right; they never returned. Later legend insisted that they had in fact made a landfall in Japan and stayed there. A second expedition was dispatched in 215 BC. This did return but without news of the elusive islands. A third expedition was planned in 210 BC though apparently delayed until a large fish could be eliminated. This was more probably a sea monster – the emperor had had a dream about it destroying his fleet. He therefore took to carrying a crossbow as he continued up the coast and eventually had the satisfaction of shooting dead just such a creature. It was his last victim. Days later he himself died.

Most of which could, again, be fabrication. Though unworthy of such an esteemed historian as Sima Qian, it could have been inserted in the Shiji by others after Sima’s death. Yet a century later a very similar interest in immortality and in locating the ‘Islands of Paradise’ would obsess the Han emperor Wudi, and in his case it is too well attested to be dismissed. The Shang kings had submitted their dreams to oracular scrutiny; they and the Zhou had had to face down monsters. Indulging ideas that posterity might consider fanciful, or tastes it might consider excessive, amounted to an ancestral prerogative. Whatever legalist logic or Confucian morality might make of such foibles, they were probably widespread in an age riddled with cults and rife with superstition.

Nowhere are the First Emperor’s fantasies better demonstrated than in Sima Qian’s description of his tomb. The site having been selected when he first came to the throne, by the time of his death a veritable mountain had been constructed upon it. Round about, beyond its double walls, were laid out the subterranean chambers in which replicas of his army and other mortuary accompaniments would be ranged. Human sacrifice as part of the funerary arrangements had not yet been abandoned. Consorts and concubines who had borne the emperor no children were ordered to join him in death, along with perhaps thousands of craftsmen and labourers whose intimate knowledge of the burial chamber might prejudice its security. But in Chu, and by now in Qin, clay effigies were increasingly preferred to still-serviceable humans as grave goods. They cost less, lasted longer, and when mass produced like the First Emperor’s terracotta warriors, could be replicated ad infinitum.

The 700,000 colonists sent to work on the tomb were housed near by. There too were located their stores, furnaces, kilns and assembly lines. A similar complex, scattered somewhat farther afield, is growing up today, such is the demand for terracotta replicas and souvenirs from what is becoming China’s foremost visitor attraction. But two thousand years ago Sima Qian had words only for the centrepiece of the necropolis. Deep beneath the mountain itself was the emperor’s great domed burial chamber.

They dug down to the third layer of underground springs and poured in bronze to make the outer coffin. Replicas of palaces, scenic towers, and the hundred officials, as well as rare utensils and wondrous objects, were brought to fill the tomb. Craftsmen were ordered to set up cross-bows and arrows, rigged so that they would immediately shoot down anyone attempting to break in. Mercury was used to fashion imitations of the hundred rivers, the Yellow River and the Yangzi, and the seas, constructed in such a way that they seemed to flow. Above were representations of all the heavenly bodies, below, the features of the earth. Whale oil was used for lamps, which were calculated to burn for a long time without going out.27

Until 1974, when some well-diggers chanced to shovel down into those chambers teeming with clay warriors whom Sima Qian had not even deemed worthy of mention, all this too was considered fanciful. No grave could possibly contain towers and palaces, seas of mercury, a cartographic model of the kingdom and a replica of the sky at night. The tomb had reportedly been ransacked and destroyed on several occasions, most immediately within five years of the emperor’s interment. The shattered condition of the terracotta troopers seemed to bear this out. Laboriously reconstituted and remustered, they, and not the tomb itself, whose location was still uncertain, became the stars of late-twentieth-century Chinese archaeology.

Yet since that 1974 discovery, barely a year has gone by without further revelations from the great necropolis outside Xianyang. More pits containing more warriors have been opened. Others have yielded skeletons, half-life-size carriages and life-size bronze replicas of geese and cranes. One is supposed the tomb of the First Emperor’s grandmother. Meanwhile the location of the main burial chamber has been pinpointed about a kilometre from the warrior pits beneath its now greatly eroded mountain.

At the time of writing (2008) the tomb remains unopened, its secrets unrevealed. Officially it awaits the development and approval of techniques and treatments that will ensure the preservation of its contents. Conflicting authorities – scientific and archaeological as well as party, provincial and central – may also be involved. As with the Tarim Mummies, national caution excites international impatience. But no one can accuse the authorities of not whetting archaeological appetites. Surveys, scans and probes have established that the great cavity of the burial chamber is still intact, neither choked with infill nor submerged in water. Traces of mercury, presumably from the seas and rivers that flowed so ingeniously across the emperor’s replica domain, have been detected; and their distribution has been scanned and charted to produce an almost recognisable map of China. The roof’s planetarium may still twinkle, the crossbows stand ready to fire, and among ‘the hundred officials’ a life-size Li Si could be waiting, bookless, by his patron’s nested coffins. Within the chamber, there may still reign that minutely regulated peace and order on which the First Emperor so prided himself in his inscriptions; but without, all semblance of decorum had been shattered almost before he was laid to rest.

4 HAN ASCENDANT

210–141 BC

QIN IMPLODES

NEARLY ALL THAT IS KNOWN OF the First Emperor and his book-burning chancellor comes from a book. In a culture as literary and historically minded as China’s, biblioclasts needed to beware; books had a way of biting back, and sure enough, both emperor and chancellor would be badly bitten. Ostensibly Sima Qian’s Shiji, one of the most ambitious histories ever written, was a direct response to the First Emperor’s assault on scholarship. Sima Qian saw his task as salvaging what he calls ‘the remains of literature and ancient affairs scattered throughout the world’ as a result of the Qin proscription, and then organising and presenting them in a form that would edify and instruct future generations.1 Confucius had expressed the same idea at a time when the ‘warring states’ were going to war, and like him, Sima Qian considered his role to be that of ‘transmitter’, not creator. But since all the earlier annals and commentaries (‘Spring and Autumn’, Zuozhuan, Zhanguoce, etc.) stopped short of the Qin unification, and since later histories would start with the first Han emperor, the Shiji would be the only work to deal with the intervening Qin triumph and implosion. By happy coincidence, the most dramatic upheaval in early China’s history is covered exclusively by its foremost historian.

Written about a hundred years after the fall of Qin, the Shiji (usually translated as ‘Records of the [Grand] Historian’) is by no means limited to that period or to what might then have been regarded as the recent past. Its 130 chapters span some 3,000 years, a remarkable perspective in a work of the second-to-first centuries BC. When later enshrined as the first of the eventually twenty-four ‘Standard Histories’ (one for each ‘legitimate’ dynasty) it served as a sort of ‘Book of Genesis’, beginning the narrative of China’s history and carrying it forward from its myth-rich dawn and the Five Emperors, through the Three (royal) Dynasties of Xia, Shang and Zhou, including the ‘Spring and Autumn’ and ‘Warring States’ periods, and on to the Qin and Han. Although it set the pattern for all the later ‘Standard Histories’, it is in fact the only one that deals with more than a single dynasty.

Not simply a dynastic record, then, it is not simply a history either. Besides recording and organising the past – and introducing such still-useful graphic conventions as year-by-year timelines and state-by-state tabulations – the ‘Grand Historian’ had much else on his mind. There were lessons to be learned, mistakes to be corrected, reputations to be revised and wrongs to be righted. It was not just a question of dishing out praise and blame or of raiding the past for ammunition with which to take potshots at the present. The Shiji was to be more than just ‘a history of the world according to Sima Qian’, rather ‘a history of the world according to history’; and the ways of history being, like those of Heaven, intricate and often hard to discern, it required very special treatment.

To represent something so vast and complex, the well-flagged themes, long linear narratives and clanking chains of causation expected by the modern reader would have been inadequate. The language itself had to be exact; truth and accuracy were paramount. But latitude in the selection and ordering of the factual material still allowed Sima Qian to nudge the reader towards his desired conclusions. So did his decidedly creative use of dialogue and dramatisation; and so did the rather demanding structure of the book. Of those 130 chapters, only twelve comprise ‘Basic Annals’. Along with the chronological tables, they provide a useful framework yet make for unsatisfactory reading without the thirty subsequent chapters devoted to the ‘Hereditary Houses’ (or ‘states’) and the seventy to biographies of notable persons. To find out exactly what is happening at any given moment – and more especially why – the reader needs to familiarise himself with the entire text (four to six volumes in translation) and to command a good supply of bookmarks. It is like trying to piece together a play with, instead of the script, a sequence of the lines assigned to one actor and then those to another and so on. This fragmented approach in no way prejudices the Shiji’s veracity; but it does result in a lot of repetition and not a few inconsistencies, some no doubt unintentional but others apparently designed to hint at the mixed motives and conflicting viewpoints that beset all human endeavour.