Полная версия

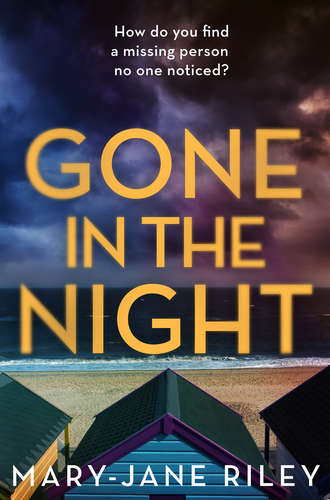

Gone in the Night

Oh, Rick, where are you?

She tried to throw herself against the side of the bin – for what? To topple it? To make a noise? No matter, however many times she tried, nothing happened. It didn’t move. No one heard her. She tried to stand up, but kept sinking down into the rubbish. She screamed, but the tape muffled her cries. It was dark. It stank. She was wet. Cold. Her throat hurt. There was no air. No air. She closed her eyes.

She had no idea how long she had been lying in the bin, but now she heard it, the noise of a lorry on the street nearby. Could it be the bin lorry coming to collect the rubbish? To collect her?

Fear made her freeze.

Light. Not light, but not dark either. Fresh air. Rain on her face.

‘Here let me help you.’

Someone – a man – leaning right over the edge of the bin, holding out his hands. She tried to shuffle towards him, carefully, so she wouldn’t sink any further into the filth. He grabbed her under her arms and hauled her up and over the lip of the bin. Her shoulders burned. For the second time that night, she landed on the hard concrete.

The man jumped down off the pile of crates he’d been balancing on, and bent to tear the tape off her head and mouth.

It hurt like hell.

He produced a knife and cut her wrists and calves free.

‘Come on. Leg it.’

A bin lorry came around the corner.

Cora held on to the man’s hand and legged it.

Chapelfield Gardens again. Cora sat down on a bench.

Her rescuer wrinkled his noise. ‘You stink.’

Cora looked at him, at his trousers held up by a tie, his stained knitted jumper underneath a buttonless coat out of which protruded much stuffing. ‘You can talk.’

Her rescuer grinned. ‘Maybe. Glad I got you before the crusher did.’

Cora nodded, then began to shiver. ‘How did you know I was there?’

Her rescuer shrugged. ‘A man gave me some dosh, told me where you were and told me to get you out. Preferably before the lorry.’

Now Cora laughed. ‘Thank you. Do you know who the man was?’

He shook his head, putting his finger to his lips. ‘Hush money, that’s what he said.’ And he ran off down the path.

Cora couldn’t stop shivering.

DAY ONE: LATE EVENING

Alex hunched into her coat and pushed one hand as far down into a pocket as she could. The other held her phone with the torch light on so she could see her way. The weather had turned from clearsky cold to stormy in the time she had been at the charity event. If she looked at the ground, the wind wouldn’t whip across her skin. The stars were hiding behind furiously dark clouds.

It hadn’t been her greatest idea. To attempt to order a taxi to come to the middle of nowhere on a weekday night. Or any night, thinking about it. It wasn’t as if she could call an Uber, or that there was a plethora of taxi firms in the area. The two firms that did answer her call said they were too busy. Alex imagined them shaking their heads ruefully as they put the phone down.

Why hadn’t she ordered one earlier?

Because she hadn’t realized she would need one.

So she began to walk, reasoning that it wasn’t too far to Woodbridge. And when she got a decent signal again, she would give one of the taxi firms who hadn’t picked up another try. Or, when she reached the Dog and Partridge, where she’d had supper with David, she might be able to persuade the owner’s student son to take her home for a bit of cash.

On reflection, perhaps she should have let Jamie Rider drive her home. Still, she’d had a lucky escape from David. Where had that mauling come from? She hadn’t encouraged him; there was no way she was even interested in him. Or anyone, for that matter, especially now her life was coming together at last. She didn’t feel as though she was being buffeted by the winds of chance any more and was finally feeling at peace with herself. The guilt that had weighed so heavily on her for years had lifted. She had a new start. Finally, she knew she deserved it.

All she needed now was a juicy story to get her teeth into. It was all very well having a bestselling book – and she wasn’t complaining, it had bought her independence as well as the new flat – but she did want to be taken seriously. She’d been writing features for The Post for a long time now. She wanted something else, something worth doing. She’d had a taste of it eighteen months ago when she was delving into the proliferation of suicide forums on the Internet and the financial shenanigans of the previous editor and owner of the newspaper. She’d enjoyed writing that copy.

The rain began to fall, gently at first, then it came on harder, running icily down the back of her neck. Damn. She was going to get properly wet now. And cold. She tried to protect her phone. It would be the last straw if that was ruined. And her feet were hurting. Those damn heels. Why hadn’t she brought flat pumps to change into? Because she hadn’t thought she was going to have to walk home, had she?

She had talked to Heath about more work, about her desire to be taken more seriously. Heath, whose looks, charm and inherited wealth belied a sharp operator, was the owner of The Post as well as its news editor. He wanted to be hands-on, he’d told Alex during one of her rare visits to London. She had told him she wanted more excitement in her working life. He’d stretched out his long legs, pushed his floppy fringe out of his eyes and said, ‘Well, you don’t want a staff job on The Post, I know that. Don’t sit around moaning, Alex. You’re a freelance, a self-starter, even if you do have enough money at the moment. It might not always be like that. You call yourself an investigative journalist, so get out there and find something to investigate.’

Tough love.

For a few days she’d been hurt, resentful, but she knew he was right – damn him. It was up to her to find stories, to get stuck into something.

Her phone buzzed. She peered at the screen. Her sister. Her heart used to sink when she got a call from her, but now it was like being phoned by someone – ordinary, was that the word? Probably not. Normal? What was normal these days? What she meant was that she didn’t go into worry mode as soon as her sister’s name cropped up on her phone. Or in conversation.

‘Hey, how’re you doing, Sasha? It’s a bit late.’

Though she knew her sister didn’t sleep much, not these days. She might be stable, her mental health issues on an even keel, but sleep was the one thing that eluded her. Too many thoughts in her head, she’d told Alex. Too many regrets.

‘Alex, guess what?’ Her sister was bubbling with excitement. No preamble. ‘There are critics coming up from London for my exhibition. Real-life critics want to view my paintings. Mine! What if they don’t like them? They might hate them. You will be at the preview, won’t you? You will be there?’ Her words came rushing out, tumbling over each other.

‘Whoa, slow down, Sasha,’ said Alex, smiling at the sheer joy in her sister’s voice. ‘Of course I’ll be there. It’s at that swish gallery in Gisford, isn’t it? I’m not far from it now, actually.’

‘Really? Is that where the charity do was then?’

‘Nearby. A big farm. Big landowners. Pots of money.’

‘I know the ones. Pierre told me about them.’

‘Pierre?’ Alex grinned even though Sasha couldn’t see her.

‘The gallery owner. And not my type. So, you know where it is, there is no excuse for you to miss it.’

‘I wouldn’t miss it for the world. The date’s in my diary.’

‘I’m so glad you’ll be there. It wouldn’t be the same without you. Can you believe it? Extremely famous people have exhibited there and now me. Me. I hope Mum’ll come too.’

‘You deserve it, Sasha. You’ve worked hard.’

‘So how was the charity gig? You were going with that bland bloke, weren’t you?’

‘David. And he’s not bland. His work is very interesting,’ she replied, tartly.

‘So how was David?’ Her sister was teasing her.

‘The do was a bit dull, in all honesty. And David was, well, not for me, shall we say.’

‘Do I detect something not right, my darling sister?’ There was amusement in Sasha’s voice, and it gave Alex such pleasure to hear it. For years her sister had been so very fragile, doubled under the weight of guilt from which Alex thought she would never recover. But she had, as journalists such as herself were fond of saying, ‘turned her life around’, and was making a pretty good success of her art – something she had started as a hobby only relatively recently, but a hobby that had turned into a passion, and a passion that was quickly becoming a career.

‘Put it this way—’ Alex began, but then her words were interrupted by a beeping sound. Damn. The phone battery must be low. ‘He was persistent.’

‘And?’

Beep. She knew she should have charged her phone before she left home.

‘And, nothing.’ Alex suppressed a shudder as she saw in her mind’s eye those wobbly lips coming towards hers. ‘He’s not my type,’ she said, briskly. ‘Worthy and all that, but not my cup of tea.’

Beep.

‘So you won’t be bringing him to my preview?’

‘No.’

‘That was pretty definite. Anyway, I must go. Art to create and all that. See you.’

‘Sash, hold on—’

But her sister had gone. Damn. She’d been about to ask her to phone a mate to come and fetch her.

Beep.

And that was it. The battery was dead.

‘Bloody hell,’ she muttered, shaking it as if that would bring it back to life. ‘Stupid, stupid woman.’

Definitely dead. No chance to ring Sasha or anybody else now.

She looked up. The light was fading fast. The wind was even sharper now, and the rain like needles on her face. There was a slight ache behind her temples. She didn’t think champagne was meant to give you a hangover. And she had drunk plenty of water. She bent her head lower and trudged on, regretting once more declining that offer of a lift. Her hands were numb, even inside her gloves.

All at once she became aware of a flickering orange light in her peripheral vision. Was she imagining it? Was her brain more alcohol-fuddled than she realized? On. Off. On. Off. She began to walk more quickly.

There. She peered down and could just about make out marks on the road. Skid marks?

She stumbled on.

Then, around a corner and out of the dark loomed a vehicle on its side in the ditch with an indicator light flashing lazily. She hurried towards it.

Judging by the tyre marks and the torn vegetation the Land Rover – for she could see it was that – had lurched from one side over to the other, then hit a tree before coming to rest in the ditch.

The front of the vehicle had caved in and the windscreen had been smashed to smithereens. Glass littered the road and the verge. A strong smell of petrol made her head hurt even more. Christ. Gingerly, she made her way over to the open driver’s door. No one inside. She looked in the back. Nothing. Then she heard a groan coming from a few feet away.

A man was lying on the ground like a ragdoll, his clothes half-flayed off him, his face a bloody mess. He groaned again. Rain diluted the blood that ran off him in rivulets. She hoped he looked worse than he was.

She knelt beside him and took his hand, swallowing hard. ‘It’s going to be okay. I’m here. You’re going to be all right.’ Her tears welled up at the lie.

‘Cold.’

Alex shrugged off her coat and laid it on top of him. ‘There. Now look, I’ve got to leave you.’ She peered into the unyielding darkness, wondering where the nearest house was. She thought she wasn’t too far from the pub, but how far? What did she reckon? The darkness was oppressive, and she had lost her bearings. The pub could be around the corner or a mile away.

‘No.’ A hand gripped her wrist strongly. ‘Don’t leave.’

She put her hand over his. ‘I’ve got to. I’ve got no battery on my phone, I can’t even make an emergency call. I need to fetch help. Do you understand?’

‘Yes. Don’t go. They’ll come. Here,’ she felt him press something in her hand, ‘take this. My sister—’

‘Please. Don’t talk.’ Her voice sounded desperate and she knew it. She was desperate. She had to get help – he was in a bad way.

She crumpled the piece of paper in her hand while trying to tuck her coat around him, oblivious to the fact that she was becoming soaked through. His skin was clammy. His breathing was becoming laboured. She could hardly bear to look at his poor, bloody face, but she made herself, and there was a flicker of recognition in her brain. He was wearing a gold chain. That, like his face, was familiar. She’d seen this man somewhere before, she was sure of it.

Before she could process the thought, she heard the sound of a car coming fast along the road. Thank God, thank God. ‘Help is coming,’ she whispered to the man.

His eyes opened. They were dark pools among the blood and torn skin.

‘It’s going to be okay, I promise.’

‘No,’ he said. His eyes closed. ‘It’s not.’

Alex leapt up as she saw headlights careering towards her and waved frantically. ‘Stop. Please stop.’

Two men jumped out of the car and hurried over to her.

‘You have to call the police. And an ambulance. There’s a man who’s been seriously hurt—’ Alex could hardly get the words out in her haste.

‘It’s all right,’ one of them said, turning the collar of the red Puffa jacket that strained against his body up against the rain and walking over to the injured man. ‘We’ve got this. We’ll take him to hospital.’

‘We shouldn’t move him.’ Alex was agitated. She wanted proper help. People in green with stethoscopes. The reassuring lights and sound of an ambulance. Her head throbbed.

The man shook his head. ‘Can’t call an ambulance. No signal.’

‘But—’ She was going to say she had been on the phone to her sister not long before, though she did know there could be a decent signal one moment and none the next in this part of the world.

‘If we don’t take him to hospital he might die anyway.’ The man in the too-tight jacket whipped her coat off the injured man. ‘This yours?’

Alex took it back and put it on over her wet clothes, then realized she was still clutching the bit of paper the injured man had given her. She shoved it into her pocket.

The two men heaved the injured man into the car, almost stuffing him onto the back seat. He groaned in pain.

No, this wasn’t right.

Alex had a half-memory from a First Aid course she had done years before that told her a casualty shouldn’t be moved if at all possible. But then, even if there was a phone signal, how long would it be before an ambulance came to this rural road? Perhaps the only answer was to let these two men take him to hospital.

‘Be careful, you’ll hurt him even more.’

‘Don’t worry.’ The second man turned to her. His dark wool coat was glistening with raindrops and he had an unmistakable air of authority. ‘We’ll get him to hospital.’

‘Which one?’

‘Which what?’ He shut the car door on the injured man as the man in the red Puffa went to the driver’s door.

‘Hospital. Oh never mind, just get him there, will you. And hurry, please.’

‘Don’t worry, we will.’

‘Hang on,’ she said. ‘Here.’ She delved into her bag and pulled out a business card. ‘Take this. Give the police my number. They’ll probably want to talk to me. And could you let me know—’

‘Police? Yes, of course. I’ll call them.’ He snatched the card from her hand. ‘We’d better get going.’ He jumped into the car and it drove off, wheels spinning on the tarmac.

Alex watched it go. Something didn’t feel right. But her head was fuzzy and she couldn’t grasp what was wrong.

The orange indicators of the crashed Land Rover continued to flash, and in the strobing light Alex saw a solitary trainer, soaking in a bloody puddle.

DAY ONE: LATE EVENING

He was in a car, he could hear an engine, feel his body jar as it went over bumps.

What had happened to him?

A crash, that was it. Driving too fast. Something on the road. A deer? A deer on the road. Hit his head. Hard. Men came. How many? Two? Was there someone else there as well? Think, for fuck’s sake, think. It was all just out of reach. The men picked him up and tossed him in a car. He was hurting and he wanted to cry out, but he didn’t. Again, instinct kicked in. He played dead. Almost dead. He was in a bad place.

The car stopped. The two men in the front seemed to be arguing. Something about ‘cover it up’ and ‘as if it hadn’t happened’. What was that all about? One of them banged the steering wheel.

He tried to open one eye. Couldn’t. Stuck. Rubbed his hand over his eyes, Christ his hand was sore, then managed to open them, a little bit.

The men were getting out of the car. He strained to listen to their argument. He couldn’t make out any words, but he could smell salt, diesel. A port?

Wait a minute. The estuary again. They were going to take him back. Where to? He didn’t know, couldn’t remember, but he knew suddenly and with absolute certainty that if he went back he would never leave.

He emptied his mind of all extraneous thought and concentrated on moving his limbs. He ignored the pain that shot through his shoulder as he tried to open the car door as quietly as he could, praying they hadn’t put any internal locks on. The two men were still arguing.

He held his breath as the door opened. He rolled off the seat and onto hard concrete, jarring all the bones in his body that were already screaming with pain. He could hear the men’s argument more clearly now.

‘We keep quiet about this, right?’ The first man’s voice was gruff, slightly accented. Local? He wasn’t well enough versed in the Norfolk and Suffolk accents to be sure.

‘They’ll find out, you know that.’ Definitely Essex.

‘Look, we get him back, patch him up and he’ll be back at work in no time.’

Back at work. Flashes of memory. Taken underground. Kept underground. Packing boxes. Trying to talk to others who were doing the same thing. Learning they’d been taken. Taken? What did that mean?

Rick heard one of the men inhale deeply, then he saw a cigarette butt thrown onto the tarmac and ground underfoot.

Hurry, his brain screamed. Hurry.

Through sheer force of will, he made himself get onto his hands and knees – Christ, that hurt – and he started to crawl away. He glanced around, trying to take in his surroundings. There was no light from the moon or stars. As his eyes grew accustomed to the dark, he made out a few cars parked here and there, an unlit streetlamp. He had painfully made his way to one of the other cars. Now what?

He heard footsteps, running. Expletives, not shouted but spoken quietly, angrily. They were looking for him. He saw their shoes coming nearer to the car. They were going to find him. Then:

Laughter. Chatter. A group of people? The laughter died away. ‘Can we help you?’ a voice called. Friendly.

‘No.’ Rude. aggressive.

‘From round here, are you?’ The voice was less friendly.

Rick chanced a look around the back of the car. He saw the two men who had picked him up with their backs to him. They were facing a crowd of, what? Six, seven men? Maybe out of the pub, walking off the booze. The right side of aggression. For now.

‘Look,’ said the first man, the one in the smart coat, ‘we don’t want trouble.’

‘Nor do we,’ said the group’s spokesman. ‘Gisford is a quiet little village where nothing happens because we don’t want anything to happen and we always remember strangers.’

‘Okay, okay. We’re going.’

The men who were trying to take him somewhere he didn’t want to go – wherever that was –got into their car and drove off, fast. Where were they going? And how long before they came back looking for him? He didn’t have much time.

The laughing group wandered away, and Rick slowly came out from behind the car.

He was on some kind of harbour front. Concrete. The sea lapping at the edges. Across the water – the estuary he had swum across? – there were lights. Is that where he had come from? He had a bad feeling in his gut about the island across the water.

Keeping to the shadows, he limped away from the sea as fast as he could and towards a small road. It was dark, apart from the odd twinkle of light here and there from behind an upstairs window of a house. It was late then.

Better keep away from people. Vehicles. They might come back for him.

He set off down the narrow lane, looking for a gate or somewhere he could get off the road and hide. But there was nothing.

Then he heard an engine. A car. Had to be them.

He crouched down, then rolled under – thank fuck – a hedge, hardly daring to breathe.

The car went past him. Slowly.

He was comfortable here. Wanted to sleep. Only for a minute.

He closed his eyes.

Rick thought he remembered French doors opening out onto a stone-flagged patio. A small retaining brick wall. A table and chairs and parasol. Green parasol. Maybe grey. Did it matter?

It did.

His whole body ached.

He kept his eyes tightly closed, shutting out the cold and the dark, the sound of a tap dripping and the dank smell of rotting vegetation, and tried to feel the warmth of the sun on his head and the scent of newly mown grass in his nose.

He thought hard.

There was laughter, he was sure of that. A child’s voice, pure and high. His child? Sister? Brother? His head was so muddled. Had been for years. He shivered but felt the sweat roll down his back.

Wait.

Back to the sunshine.

A woman. Small. Blonde. Smiling at him. His wife. Her name? What was her goddam name? He wanted to cry out in frustration, but something told him to keep silent. Helen, that was it. But as soon as he thought of her name the dark began to roll in again. Why? What had he done?

Water. He’d swum across the estuary. Dark. Cold. He’d climbed into a car – hadn’t he? Yes, yes. He’d been on his own, though he’d wanted to take Lindy. But she didn’t make it. Why not? What happened? Was she here?

And who was Lindy?

The blonde woman? No. She was definitely Helen. Don’t think about Helen.

And he’d left something behind, something important.

He shivered. And realized his body was a mass of aches and pains. He ran his tongue around his mouth and felt a couple of loose teeth. Tried to lift his head.

Fuck that hurt.

He gritted his teeth. Lifted his head again. Let it fall back. Too much pain.

Where was he? It wasn’t hot enough to be the desert, not cold enough to be Norway or Russia, so where the hell was he?

He could do this, he’d been trained to withstand all sorts. He’d been trained by the—

What was he thinking? That he’d been trained by the army. Fuck, yes. Heat. Desert. The girl with the almond eyes. Push them away.

Army. That’s who he was.

He opened his eyes. Saw brown spikes and brambles. His face throbbed. The dripping tap was rain falling off tree branches onto the ground beside him. Cold seeped through him from the earth. He was under a hedge? What?

He flexed his fingers, tried to move his legs, his arms. Instinct told him to keep his movements small and quiet. There had to be a reason he was under a hedge.

Hiding?

That had been such a bad idea. Could have been fatal.

He had no idea how long he’d been under the fucking hedge, but he had to gather himself and move. Even more, he needed to feel his body – at the moment he was numb and that was not a good thing.

Trying not to cry aloud with the pain of it, he rolled out from under the hedge and onto the road.

The full force of the rain hit him hard, opening the cuts on his face, and within moments he was soaked through. At least, he thought grimly, it would wash away some of the blood and the dirt and the grime.