Полная версия

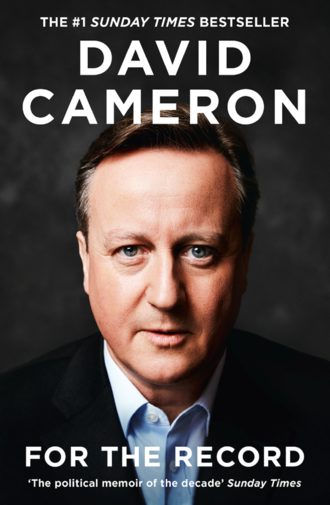

For the Record

The context was this. MPs were entitled to claim an ‘Additional Cost Allowance’ (ACA) of up to £24,000 per year for running a second home, because they have to be based in Westminster for part of the week and in their constituency for the rest of it. There was also £22,000 of ‘Incidental Expenses Provision’ for office expenses, over and above the salaries for staff. Rules about employing relatives as members of staff were virtually non-existent.

The ACA in particular was treated by many as if it should be claimed automatically. Over many years the salaries of MPs had been held back – usually for political reasons – and their allowances increased instead. Often, MPs would just send a load of receipts in to the Commons Fees Office and let them decide what household expenditures or repairs should qualify.

Our party had a taste of what was coming when it was revealed that there was little evidence of what MP Derek Conway’s researcher, his son, had done to earn the thousands of pounds he’d received at the taxpayer’s expense.

Labour experienced its own preview of the scandal when some receipts for which home secretary Jacqui Smith had been reimbursed were published. They included two pay-per-view pornographic films, which her husband soon owned up to.

I knew I had to act fast. I made sure all our MPs filled out a ‘Right to Know’ form that provided the basic details of their expenses claim and whether they employed any relatives. These would be made public.

Labour’s reaction was to continue to attempt to keep the problem under wraps. Leader of the House of Commons Harriet Harman wanted the House to vote to ensure that MPs’ expenses were exempt from the Freedom of Information Act. But it was too late. The Daily Telegraph bought a stolen disc with every MP’s expenses claims set out in full, receipts and all. Day after day it published the details. Determined to remain ahead of the game, I called a press conference at the St Stephen’s Club. My response included an apology and a roadmap – and I didn’t conceal my anger about what had been going on: ‘Politicians have done things that are unethical and wrong. I don’t care if they were within the rules – they were wrong.’

I set up an internal scrutiny panel, a so-called Star Chamber, including my aide Oliver Dowden, known as ‘Olive’, who I also called ‘the undertaker’, since he so frequently brought me the bad news. The panel, assisted by a team that was combing through all the information, would examine the expenses claims of every Tory MP, and would decide who had to pay money back. Anyone who refused to comply would lose the whip. This was faster and firmer than the Parliament-wide independent inquiry that Brown would set up, and showed that we had understood the severity of the situation and had gripped it early.

The whole thing became a daily ordeal. The Telegraph would call up in the morning, give us details about whose expenses they were going to expose the next day, and allow us until 5 p.m. to respond. Ultimately the call – both the judgement call and the phone call to the MP – had to be made by me.

The calls included some of the strangest conversations. ‘Your entire family were working for you?’ ‘Why do you need a ride-on lawnmower?’ ‘What does your swimming pool have to do with your parliamentary duties?’

As before and since, I always tried to give people a chance to explain their situation, rather than being driven by arbitrary deadlines. But it was hard. Some colleagues didn’t help themselves by taking to the airwaves. Anthony Steen became one of the most famous examples. Having claimed over £80,000 for the upkeep of his country house, including rabbit fencing and tree surgery, he insisted to BBC radio that he had behaved impeccably: ‘I’ve done nothing criminal, that’s the most awful thing, and do you know what it’s about? Jealousy. I’ve got a very, very large house. Some people say it looks like Balmoral …’

He had to go.

I had to deal with Peter Viggers, who had claimed, among £30,000 of gardening expenses, for a £1,600 ‘floating duck island’. With Michael Ancram, whose swimming-pool boiler was serviced at taxpayers’ expense. With Douglas Carswell, who put a ‘love seat’ on expenses. With John Gummer, whose moles were removed from his lawn using public funds. It just seemed to go on and on, and to get weirder and weirder.

Then there was Douglas Hogg, who was, according to reports, reimbursed by the taxpayer for having his moat – yes, moat – cleaned. To be fair to him, he had never actually claimed for this directly. He had given all his receipts to the Fees Office and, satisfied that they added up to far more than the ACA, they had just given him the full amount. I could see his point. He was doing what he had been told to do. It was all within the rules. But, as Andy put it, the point was that he had a bloody moat.

There were some heart-rending examples at the other end of the spectrum. One MP who was asked to pay back thousands of pounds was desperate not to do so, both because it would look as if he was admitting guilt when there was no impropriety, and because as a young MP with a large family he genuinely couldn’t afford to.

The sheer, granular detail being unearthed made the scandal run and run. Receipt by receipt, the Telegraph gave an insight into MPs’ lives – and revealed a class that seemed completely out of touch with normal people. Never mind that most MPs had claimed only for rent or mortgage interest payments or the odd piece of IKEA furniture, and had been urged by the authorities to claim even more. The colourful examples stood out, showing a world of ride-on mowers, moats and mole-free lawns.

Of course, I had a colourful example of my own – violet-coloured, to be specific.

I had only ever claimed for the mortgage interest on my constituency home. It was a simple approach, specifically permitted by the rules, and seemed to me to be clearly within the spirit of what was intended. But one year I had an extra bill, which I handed to the Fees Office. Ordinarily this would have been logged as ‘maintenance’, and would have attracted absolutely no attention. Except, like a good West Oxfordshire tradesman, my builder had detailed the work he had done: ‘Cleared Vine and Wisteria off of the chimney to free fan.’ As with so many other claims, it was the detail that did for me. People still ask me how my wisteria is doing today.

Every party was embroiled. Which meant we could only fix the broken system if we worked together.

In fact, before the scandal broke I went to see Gordon Brown in his Commons office with Nick Clegg to see what the three main party leaders could do. He gave us a take-it-or-leave-it proposal: a per-day allowance for MPs – not all bad, but far from right.

Had we been with Tony Blair, the three of us could have thrashed out something workable. With Brown, it was pointless. He was sullen and stubborn, and couldn’t hide his contempt. Clegg and I both concluded that it was impossible – he was impossible.

What were the long-term implications of the expenses scandal?

We lost a lot of good MPs, as people who weren’t even guilty of any wrongdoing, such as Paul Goodman, left Parliament.

The British Parliament is one of the least corrupt in the world, but it would be forever tainted. I believe deeply that people go into it to make a difference and to serve, not to see what they can get out of it. Yet ever since 2009, my postbag has been full of letters about how venal our MPs are.

It left many Tory MPs feeling aggrieved with me. They felt that the system I had set up to clean house made them look as though they had done something wrong, when they felt they hadn’t. At one point Andy walked into my office and said there was a serious chance of rebellion. I said I didn’t care. ‘This is the right thing to do – if it’s going to take me down, then so be it.’

So while it stored up bad feeling between me and some in the party, I don’t regret the position I took. Politics ended up with a model that was more transparent and that cost far less, and our party drove that.

In the normal course of things the searchlight might land on politicians once or twice a year, but its harshest glare is saved for momentous events like the financial crash and the expenses scandal. Under that intense scrutiny, I thought we had demonstrated that we were the party with the answers not just to a broken society, but to a broken economy and broken politics too.

But we were also suffering from our own broken – a broken promise.

In 2004, Tony Blair had pledged to hold a referendum on a proposed European Constitution, but it was rejected at plebiscites in France and the Netherlands.

The European powers went back to the drawing board and came back with the Lisbon Treaty, which retained many of the elements of the constitution – creating an EU Council president, foreign minister and diplomatic service, eliminating national vetoes in many areas, and paving the way for more vetoes to be eliminated.

We argued straight away that if the government had said it was going to have a vote on the constitution, it must have one on this treaty – especially since it was more significant and far-reaching than its immediate predecessors, Nice and Amsterdam. I was clear about the lessons from Maastricht: it was right to give people their say on such important changes.

I thought – I still think – that Labour’s failure to hold the referendum it had promised in 2004 was outrageous. It had managed to avoid all questioning on the European constitution during the 2005 election campaign by saying it would be subject to a separate vote. And then it didn’t hold one. So in the Sun in 2007, as the treaty was still being negotiated, I gave a ‘cast-iron guarantee’ that a Conservative government would hold a referendum on any EU treaty that emerged from the negotiations.

In 2007 it seemed entirely likely that we would be able to fulfil this if we entered government, since we all thought that the Parliament wouldn’t run its full course to 2010. But as Brown delayed, member states had the time to ratify and implement the treaty – including the UK, which did so in July 2008.

By 2009, our last hope was the Czech Republic. I wrote to the president, Václav Klaus, pleading with him to wait until after a UK general election before he ratified the treaty. But he replied that he could not hold out that long – another eight months – without creating a constitutional crisis. The Czech Constitutional Court ruled against the one remaining challenge to the treaty, and Klaus signed it that November. On 1 December the treaty was passed into law. Our promise to hold a referendum on it was redundant.

I gave a speech declaring that a Conservative government would never again transfer power to the EU without the say of the British people, and that any future treaty would be put to a vote. (True to our word, we made this ‘referendum lock’ law in 2011.) In that speech I talked about ‘the steady and unaccountable intrusion of the European Union into almost every aspect of our lives’. I said: ‘We would not rule out a referendum on a wider package of guarantees to protect our democratic decision-making, while remaining, of course, a member of the EU.’

I could feel the pressure on Europe quietly building. The anger at the powers ceded at Maastricht and since was reawakened by the denial of a referendum on Lisbon. The anger was not just coming from the usual suspects and the Eurosceptic press, but from constituents and moderate MPs. I felt it too. I was thinking intensively about the issue, and about how to make this organisation work better for us. And I was clearly stating that a referendum of some sort might be on the cards at some point in the future.

11

Going to the Polls

There haven’t been many general elections in this country at which voters have shifted en masse from one party to another. The Liberal landslide of 1906, Clement Attlee’s triumph in 1945, Margaret Thatcher’s victory in 1979, the rush to New Labour in 1997 – these are remembered as some of Britain’s great swing elections, whose winning governments went on to change the course of our history.

As 2010 approached, I knew I needed to perform a similar feat. It wouldn’t be enough just to take a few extra constituencies. We would have to win 120 more seats, and retain all our existing ones, if we were to have any hope of a majority. No Conservative had achieved anything like it since Churchill in 1950, and even he fell short of an outright majority and needed another election to return to Downing Street. We had a mountain to climb.

I may have had Everest in front of me, but I had the best sherpas by my side.

Thanks to Andrew Feldman we were going into the election in the strongest financial position in our history.

Stephen Gilbert, the thoughtful and reserved Welshman and campaigning powerhouse, already had our target seats identified, our candidates selected, and the volunteers geared up, ready to fight the ground war.

Andy Coulson had transformed my relationship with the media and translated the theory of modern, compassionate conservatism into something tangible and exciting.

Ed and Kate remained by my side. Gabby was joined by Caroline Preston and Alan ‘Senders’ Sendorek handling the media. Oliver Letwin was still coordinating policy, and Steve still adding his brains and buzz.

Meanwhile, Liz Sugg was poised to turn our plans into practice. At the drop of a hat she could pull together visits, rallies, interviews, drop-ins, walkabouts, anything. Haranguers were kept at bay, staff were all in position, the speech was on the lectern, and there was no danger of me being snapped in front of words like ‘exit’, ‘closing down’ or ‘country’ (there’s always the danger of blocking out the ‘o’ with your head …).

But what was the message we should take to the country? We didn’t have just one answer – we had several. One focused on fixing our broken economy. Another on mending our broken society. A third was to re-emphasise how much the Conservative Party had changed. And on which of those answers should be given priority, the team was split.

George, de facto campaign chief, and I had been making a series of speeches on the dangers of debt and the need for a new economic policy. The theme was clear: the principal task of our government would be an economic rescue mission.

Combining this with our strong attack on Labour was a single, clear message: only by removing a failing Labour government could we restore Britain’s economic fortunes. This was what Andy, running the all-important communications operation, wanted front and centre.

But it was all a bit black-skies. I had been working since 2005 with the famously blue-skies Steve on a sunnier, more optimistic focus – on how we could deliver stronger public services and a fairer, more equal society. We called the organising idea ‘the Big Society’.

I loved it. Conservatism for me is as much about delivering a good society as a strong economy. And building that good society is the responsibility of everyone – government, businesses, communities and individuals – rather than the state alone.

This philosophy – Social Responsibility rather than Labour’s approach of State Control – was summed up by Samantha when we were mulling over these concepts one evening in the garden in Dean. ‘What you’re saying is there is such a thing as society,’ she said, referencing Thatcher’s famous (but often misinterpreted) quote. ‘It’s just not the same thing as the state.’ That summed up the theory perfectly. And in practice it fell into three broad categories.

First: reforming public services. We were absolutely not, whatever our critics alleged, going to dismantle taxpayer-funded public services. But to improve those services we wanted to empower the people who delivered them – trusting teachers to run schools, doctors to run GP surgeries, new elected police and crime commissioners to run police forces, and so on. Bureaucracy and centralised control would be out, local, professional delivery would be in.

This would only deliver better results if at the same time we empowered the people who used those public services, and gave patients, passengers and parents real and meaningful choices, including the ability to take their custom elsewhere. Otherwise we would simply be swapping one monopoly for another.

Just as the Thatcher governments transformed failing state industries into successful private-sector industries, we wanted to bring the same reforming vigour to enable not just the private sector but also charities, social enterprises, individuals, and even cooperatives, or mutuals, to deliver public services. That went right down to local people being able to take over community assets like post offices and pubs.

The second element was about finding new ways to increase opportunity, tackle inequality and reduce poverty.

Since the 1960s, and particularly after 1997, the size of the state had ballooned, spending had surged, more and more power had been centralised, yet the gap between the richest and the poorest had actually increased.

In a number of important ways, the Big State was sapping social responsibility, and as a result exacerbating the very problems it set out to solve. The development of the welfare system was the classic example. Some of the interventions to tackle poverty had had the opposite effect. There were perverse incentives that deterred people from finding work or from bringing children up with two parents.

It took away people’s agency. Drug-addiction programmes, for instance, focused on replacing one addictive substance – heroin – with another – methadone – rather than encouraging addicts to go clean.

We wanted to unleash the power of what we called ‘social entrepreneurs’, usually charities and social enterprises, to tackle some of our deepest problems, from drug addiction to worklessness, from poor housing to run-down communities.

I was inspired by people like Debbie Stedman-Scott. Debbie had come from a tough background, and went to work for the Salvation Army across Britain before setting up an amazing employment charity, Tomorrow’s People, which helped people in the most deprived communities to find and keep a job. I visited it several times.

I was also inspired by Nat Wei, who helped create the Future Leaders programme, which sought the best teachers to lead inner-city schools.

And there was also Helen Newlove, who had campaigned tirelessly for the victims of crime since the murder of her husband Garry in 2007. They were amazing people. The Big Society was about empowering them.

The third element was about a step change in voluntary activity and philanthropy.

We proposed that the state should act as a catalyst, boosting philanthropy and volunteering and, for example, encouraging successful social enterprises to replicate their work across the country. That is where programmes like National Citizen Service (NCS) and training a network of community organisers came in.

In the past, we claimed over and over that Labour was the big-state party and we were the free-enterprise party. But we didn’t have enough to say about how free enterprise, or indeed any of our other values – responsibility, aspiration and opportunity – could deliver the non-economic things people needed. About how we could provide better schools. Or help people off drugs. Or transform their neighbourhoods. About how Conservative means could achieve progressive ends. The radical reforms that came under this Big Society umbrella had the potential to change all that.

Like all radical proposals, it came in for criticism.

Andy feared that the combined austerity/Big Society message sounded as if we were saying to people both ‘Let us cut your public services’ and ‘Get off your arses to deliver those services yourself’ – a miser’s mixture of ‘Ask what you can do for your country’ and ‘On yer bike.’

Other critics said I was drawing too much on my rural, upper-middle-class upbringing by advocating the Big Society. Well-off people have the time, money and inclination to dedicate themselves to local causes. Those on minimum wage who are juggling two jobs and several children do not. Yet, as I had seen, some of the most deprived neighbourhoods had remarkable social entrepreneurs and community spirit, from volunteers cleaning parks in Balsall Heath in Birmingham to mothers combatting gang culture in Moss Side in Manchester.

I thought the Big Society became more, not less, necessary in a debt-ridden world. Every government in the developed world was having to learn to do more for less – and fast. We could lead the way, and by reducing the long-term cost of social failure, we could drive down the deficit in the process.

Our failure to choose between this theme and the others could be seen in our advertising, specifically our posters. ‘We can’t go on like this,’ the billboards across a thousand different marginal seats said, next to a giant headshot of me, wearing an open collar and a serious expression. ‘I’ll cut the deficit, not the NHS.’ The message didn’t land well, because it was a sort of two-in-one. Even worse, my photo had been altered so much that I ended up looking like a waxwork.

It provided an ideal canvas for idle hands. On one Herefordshire hoarding I was spray-painted with an Elvis-style quiff, and ‘We can’t go on like this’ was followed by ‘with suspicious minds’. A website was set up for people to produce their own spoof versions. Thank God my children weren’t very old at the time. They love teasing me, and they’d have made one for every day of the week.

Yet for all the derision, it was, unlike most election posters, true. In government, we did cut the deficit. We didn’t cut the NHS.

The disagreements between the team – particularly between Steve and Andy – were never fully solved. By this point the fire-and-ice pair were deliberately assigned a shared office in the middle of the open-plan Conservative HQ, dubbed ‘the love pod’.

Sadly, uncertainty and some unforced errors were to continue, and then came a jolt from the polls on 28 February 2010. The Sunday Times front page read: ‘Brown on Course to Win the Election.’

As an opposition leader, you embark upon the final few weeks before a general election – the so-called short campaign – with exhilaration and dread.

The dread comes from the constant possibility of screwing up. The whole process of a campaign is very presidential, and the result very personal. The exhilaration comes from the fact that you’re able to break out of the media cycle and parliamentary timetable and get on an equal footing with the government.

For five years the media cycle had been a source of great frustration. In opposition, we worked hard to research and develop strong policy. If it was about schools, for instance, we would meet and talk with heads, teachers, governors, parents, academics and think-tanks. We would research what had been tried overseas, prepare policy papers, lay out the costs and the sources of funding – and then perhaps arrange a visit to something equivalent that already existed in order to accompany the announcement. It’s really strong, exciting stuff – and you set out the steps for how it’s going to change the country.

Then you switch on the news that evening and find you’ve been given twenty seconds to explain it. What follows is analysis – often reporters interviewing other reporters – not about the policy itself, but about what political advantage you are seeking by coming up with this new idea and whether or not it’s an election winner. And, of course, all this is combined with the latest plot twist of who is up or down in the great parliamentary soap opera.

On 6 April, Gordon Brown fired the starting gun for a 6 May election. I was sitting in my glass-walled office in CCHQ after our first 7 a.m. daily election meeting. Officers from the Met were on their way to give me police protection throughout the campaign. If we won, they’d probably be with me for the rest of my life. (They are the most wonderfully kind and dedicated people. And they do try to give you as much personal space as possible. A week after the election, Sam and I were out for dinner and she leaned over to me and whispered, ‘Those people on that table there – I’ve seen them before.’ ‘Yes, darling,’ I said. ‘They’re from the protection team.’)