Полная версия

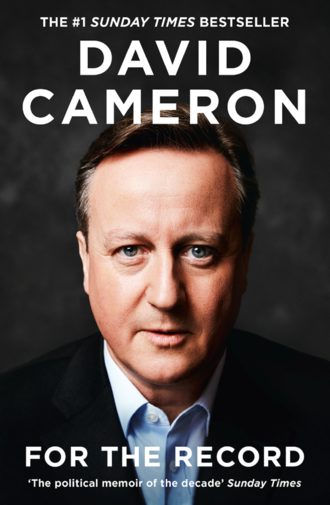

For the Record

All in all, it felt as if the campaign was stuck, and outside our small core there were few who thought we could win. But I knew we had one weapon more powerful than those possessed by any other candidate. A clear, powerful and persuasive political message that I was sure the party was ready for: Change to Win.

This oughtn’t to have seemed as radical as it sounded. After all, the essence of conservatism, and central to the success of the party, is that it adapts. Far from being the ones trashing the Conservative brand and the Conservative Party, we were absolutely convinced that we were the ones who could save them.

Our goal – which became my mantra – was a modern, compassionate Conservative Party. Modern, because we needed to look more like the country we aspired to govern. Compassionate, because our politics was about extending opportunity to those who had the least. And Conservative, because we believed that timeless Conservative principles – strong families, personal responsibility, free enterprise – were as important as ever.

The speech I made that June, effectively starting my leadership bid, included a strident defence of families and marriage. Some saw this as rather an old-fashioned note in an otherwise modernising score. I saw it as essential to building a stronger and more compassionate society.

In August 2005, I delivered a comprehensive speech on the right approach to tackling the rise of Islamist extremist terror. I made the case for tougher security measures, including action to deport hate preachers and potential terrorists, and arguing that, if necessary, we would have to leave the European Convention on Human Rights. But the real point of the speech was to make clear that I believed we were involved in an ideological struggle that could last for a generation or more. There was no point trying to tiptoe around what we were up against.

And then there was Europe. I thought, naïvely perhaps, that I had the right formula. In line with my own beliefs, we would be genuine Eurosceptics. Not arguing for Britain to leave the EU altogether, but arguing consistently and cogently for reform. Integration had gone too far. Brussels was too bureaucratic. Britain needed greater protections. Far from rejecting referendums on future treaties, the public should have its say.

Crucially, we had to get away from the ‘doublespeak’ of the past. Margaret Thatcher had railed against Brussels, yet took the country into the Exchange Rate Mechanism. John Major had attacked the single currency, yet said he wanted Britain at ‘the heart of Europe’. The Conservative government had opposed a referendum on the Maastricht Treaty, yet most ministers privately prayed for the Dutch and Danish populations to reject it when they were given the chance in referendums of their own. So, above all, we needed to be clear and consistent.

To me, it followed logically that the Conservatives couldn’t continue to sit as part of the European People’s Party (EPP) group in the European Parliament. The EPP wanted more integration and more political union; the Conservative Party wanted less of both. Yet William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard had all fudged this issue. In my view we had to act and speak in the same way whether we were in London, Brussels or Strasbourg. Thus my pledge to leave the EPP and establish a new centre-right group.

Some have said that this pledge was made purely for opportunistic reasons – to win the support of Conservative backbenchers. Others that I did not fully believe in what I was doing. I totally reject those criticisms. I was in Conservative Central Office when Margaret Thatcher was persuaded to join the EPP. I thought it was wrong at the time, and I never changed my mind. We agreed with the mainly Christian Democrat parties about many things, but not the future direction of Europe. That should have been a deal-breaker right from the start.

But would leaving the EPP do us harm with our allies? This was a stronger argument, and I suspect it was the one that encouraged my predecessors to pull back from making the full break. But our allies needed to know we were serious about reform. And I was convinced that it would be better for all of us if we were outside the EPP, while cooperating with its members on shared endeavours. This indeed turned out to be the case – we established what rapidly became the third-largest group in the European Parliament after the socialists and the EPP: the European Conservatives and Reformists Group.

Undoubtedly the move helped me win support from Eurosceptic MPs. But many of them had few other options. When it came to Europe, Ken Clarke was already the Antichrist to many. And David Davis was the Maastricht whip who had twisted arms and made MPs vote for a treaty they hated. Meanwhile Liam Fox’s bandwagon had limited momentum. So I didn’t need to make pledges on the EPP to win the leadership, or even to win the votes of the bulk of the most committed Eurosceptics. What I said to those MPs was what I believed – and I delivered the promise that I made in full.

But still there wasn’t enough support. It felt as if there were only two people – David Davis and Ken Clarke – in the race. On one occasion in my office just before summer recess, George said I needed to start thinking about packing it in. He was frank, as always: ‘Look, I don’t think you’re going to win. You’ve had a good run, made some good points, put down some strong markers – why not leave it at that for now?’

But I still thought the contest was wide open. I was more certain than ever that the party needed to change, and that change wasn’t being offered by anyone else. Yet I had a sense that for all my hard work, perhaps I was holding something back. Perhaps I was still trying to temper my radical aims, for fear of scaring too many people off. I knew now that the only way I had a hope of winning was by being true to myself, getting everything out there and going for broke on modernisation.

We had £10,000 left in the kitty, and we would blow it all on the launch, at which we would set out in even clearer terms what was on offer and what was at stake. At least then, even if I lost, I’d have nothing to reproach myself for.

Launch day turned out to be a day that changed my life.

Steve and I spent a lot of time thinking and writing, and then polishing and rewriting, the speech. Steve also spent a lot of time getting the look and feel of the launch right: he wanted it to be as different from the usual Tory leadership launches as it could possibly be. These tended to take place in a House of Commons committee room, or at least in a room that looked like one. They would involve lots of men in suits standing around, sometimes looking faintly deranged and saying ‘Hear, hear’ too loudly whenever their man (and it usually was a man) said something vaguely right-wing.

We picked a date for our launch, but soon found out that it was the same day the Davis camp had chosen. Instead of changing the date, we hoped that the contrast between the launches would demonstrate new versus old, change versus more of the same. And that’s pretty much what happened.

Sure enough, the Davis launch was in an oak-panelled room. Veterans of past Tory leadership elections said that they felt they’d seen and heard it all before.

We rented a bright and open space, with a stage and no lectern. Instead of journalists and MPs we invited friends and supporters. And instead of tea and biscuits it was fruit smoothies and chocolate brownies. Sam asked lots of our friends, some of whom, like her, were pregnant or had recently had babies.

As I stood before the crowd, I felt that this was my chance to say as directly as possible what I wanted to do, and why. I might have been timid at the start of the leadership campaign, but I would be bold when it mattered. Everything had to change. It wasn’t enough just to oppose Labour with more vigour. Nor was it enough to produce even more rad-ical policies and push them with even more gusto. ‘We can win,’ I told the audience. ‘We can make this country better, but we can only win if we change. That’s the question I’m asking the Conservative Party. Don’t put it off for four years. Go for someone who believes it to the core of their being. Change to win – and we will win.’

In one step I had gone from being the outsider to a real contender. And the stage was set for the party conference in Blackpool in just four days’ time.

The attention of the press, which had died off over the summer, was suddenly intense, and Gabby Bertin went into overdrive fixing interviews and profiles. She was joined by George Eustice, who came highly recommended having worked for the organisation Business for Sterling, which campaigned against the UK joining the euro. He was a gentle, thoughtful strawberry farmer from Cornwall, as keen as the rest of us to see the Conservative Party change. We quickly became good friends.

The week in Blackpool was undoubtedly one of the most exciting of my life. I could feel the momentum. Every day we were winning more support from MPs and candidates. Every party or event we held or at which I spoke saw more and more people turn up.

Standing in the wings of the Winter Gardens waiting to make your speech is an extraordinary feeling. Even back in 2005 the place was crumbling, but it still had some of its old magic. The acoustics were good, the hall was packed, and the audience was close to the stage. The atmosphere and the potential were tangible.

My speech was not as good as the one at the launch, but many more people saw it, as it was carried live on television and reprised on the evening news. What impressed many people was that I delivered it without notes, having memorised it as we drafted it. Watching it now I find it rather wooden, but it worked.

Within a single day, the polls were transformed: support for me surged from 16 to 39 per cent, while for Davis it collapsed from 30 to 14. Between the conference in October and the ballot in December there appeared to be nothing that might shift the dial back in Davis’s favour. And I was going to make sure of it. I resolved to go to as many places as I could, and speak to as many members as possible. For five weeks, life for Liz Sugg and me was spent on the road. Speaking at members’ meetings, sometimes with only a dozen people in the room. McDonald’s drive-throughs for lunch, a cigarette and a glass of wine for dinner at whichever Travelodge we were staying in.

Politically the only events that came near to attaining significance were television encounters. There were my first two TV debates, one on ITV, the other on the BBC. And I think it is fair to say that I lost both of them.

The face-off with Jeremy Paxman was, by contrast, something of a triumph. I enjoyed his books, his humour, and watching the spectator sport of his political interviews. But as an interviewer I thought that most of the time he was a self-indulgent monster. He wasn’t trying to get answers or inform viewers, he was just trying to make his victim look like a crook while he looked like a hero. To reverse Noël Coward’s dictum about television, I thought that Newsnight was a programme for politicians to watch rather than to appear on. Not least because hardly anyone actually watched it. I could see absolutely no point in doing an interview with Paxman: it would never be an attempt to examine policies or priorities, just an opportunity for him to show off and try to take me down at the same time.

This infuriated my team. There is nothing a press officer hates more than their boss refusing to do an interview. Eventually they wore me down, and I relented. But I was prepared to turn the tables on Paxman.

In spite of endless promises by the BBC about a neutral venue, the interview was staged at some lush wine emporium. And it soon became clear that the whole thing had been set up to try to make me look like a rich, spoilt child of Bacchus. I was a non-executive director of a company, Urbium, that owned and ran bars and nightclubs. And I should have predicted what was coming.

The first question was, ‘Who or what is a Pink Pussy?’

I paused and gulped. The only ‘Pink Pussy’ I had heard of was the notorious nightclub in Ibiza. In a split second I decided – thank God – that no answer was best.

‘What about a Slippery Nipple?’

Now I knew where he was going: Pink Pussies and Slippery Nipples were both cocktails. He wanted to get stuck into outside interests and the responsibility of drinks companies. But before he had the chance to get going, I decided to unleash my own Paxman-like rant.

‘This is the trouble with these interviews, Jeremy. You come in, sit someone down and treat them like they are some cross between a fake or a hypocrite. You give no time to anyone to answer any of your questions. It does your profession no favours at all, and it’s no good for political discourse.’

That, combined with teasing him about interrupting himself, put Paxman off his stride. He got nothing out of me, and I avoided interviews with him for the next five years. I was happy to leave it at played 1, won 1.

And then the campaign was over.

On 6 December 2005 I made my way to the Royal Academy of Arts on Piccadilly for the announcement of the count. The results were read out at 3 p.m. – and the victory was comprehensive. I had won over twice as many votes as my opponent. I had the mandate. I could get down to work.

I went straight from a celebration party for MPs at the ICA on The Mall to the rather grim green office occupied by the leader of the opposition. By the desk at one end of the room is a pair of double doors leading out to a small balcony. I sat down on the ledge and smoked a cigarette as I thought about the day ahead, which would, dauntingly, feature my first Prime Minister’s Questions.

The team met to discuss the task. We had talked a lot about supporting the government when it did the right thing, so I was fairly sure that I should make a start on education, promising to support Tony Blair in his desire to give schools more independence, particularly if he faced down the union-inspired opposition on his own benches.

I suggested that if he brought up our approach in the past, I would say, ‘Never mind the past, I want to talk about the future. He was the future once.’ George said, ‘Never mind what he says, just say that line – it’s brilliant.’ I did. I had only ever spoken from the despatch box three times in my life. The backbenchers cheered behind me.

First hurdle jumped. Many more hurdles to come.

9

Hoodies and Huskies

It was minus 20 degrees. All I could see for miles was snow. Standing on a sled, I clung to the reins of several barking huskies. ‘Mush!’ I shouted, and we hurtled across the glacier.

It had been four months since I’d taken the reins of a rather different beast. And I had decided to make Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, the destination for one of my first foreign trips as Conservative Party leader. It was dismissed by many as style over substance. But, like all the significant decisions during those early days of my leadership, it was part of a serious, thought-through political strategy.

We wanted to demonstrate in the clearest possible way that this was a new leader, a changed political party, and – above all – that the environment and climate change were issues we were determined to lead on. They were personally important to me, but they also helped to define my sort of conservatism. Concerned about preserving our heritage, aware of the responsibilities (not just the limits) of the state, able to talk confidently about new issues that might not have arisen in earlier general elections, and respectful of scientific evidence.

Yet in opposition it is hard to get across who you are, and to talk about the things you want to talk about. The government can just waltz onto the 10 o’clock news and talk about its latest plan of action, while you have to work relentlessly to try to set the agenda – but with what? Something you might do, if there is an election, if you win it and if the issue is still relevant in n years’ time.

So we were prepared to take risks. And Svalbard really was a risk. For a start, it nearly resulted in images very different from the photos of me gliding along behind the huskies. I was given a whole load of instructions about how to operate the sled. I ignored all of them, and disaster nearly struck. The cameras were set up for a dynamic, fast-moving shot of me steering the sled. I managed to turn the whole thing over at high speed, and collapsed in a ball of snow, ice and, from everyone around me, hysterical laughter.

These weren’t quite the pictures we wanted – I kept thinking of another opposition leader, Neil Kinnock, falling over on Brighton beach. Mercifully, these career-maiming shots never made it onto viewers’ screens.

Later, as we clambered into a cave, everyone was asked to wear protective helmets. I resisted, remembering William Hague’s baseball cap embarrassment as leader of the opposition. As a politician, you’re haunted by the ghosts of gaffes past.

It wasn’t long before I patented my own.

A leader of the opposition has a car from the Government Car Service to ferry them around, at least partly because they have a number of official responsibilities, and a big case of confidential papers to carry with them. I was allotted Terry Burton, who had driven some of my predecessors.

For years as an MP I had cycled to Parliament, often with George. I didn’t want to stop now that I was party leader, and very occasionally Terry would bring this case, and sometimes my work clothes, including my shoes, in to the office for me. Soon the Daily Mirror was onto me, exposing the eco-mad Tory leader’s ‘flunky following behind in a gas-guzzling motor’. The Guardian dubbed Terry a ‘shoe chauffeur’. I was truly sad that the episode had tarnished our genuine ‘Vote Blue, Go Green’ message, our slogan for the local elections taking place that very week. And I’ve never lived it down.

Presentation is important, but prioritising the environment through my trip to the Arctic really was as much about substance. We had to take a boat to visit the British Arctic Survey team, and I asked one of its members why they’d put their station somewhere that was surrounded by water. ‘Well, the water wasn’t there until last year,’ he said. It was a profound moment. Global warming was real, and it was happening before our very eyes.

So what was the governing philosophy of my leadership of the Conservative Party in opposition?

Two big things had changed.

First, at the time it seemed as if the great ideological battle of the twentieth century – right versus left, capitalism versus communism – was over. We had won. Labour now accepted the need for a market economy to help deliver the good society, and it appeared that full-blooded socialism was dead. The Conservative Party needed to take a new tack. We shouldn’t give up on our belief in enterprise and market economics, but it was time to bring Conservative thinking and solutions to new problems.

The second thing that had changed was the electorate. Over the previous twenty years Britain had become more prosperous, somewhat more urban and much more ethnically diverse. Gay people were coming out, more women were going to work and taking senior jobs, social attitudes and customs were changing. And all of this, it seemed to me, had left the Conservative Party, one of the most adaptable parties in the world, behind.

I saw myself, however new and inexperienced, as inheriting the mantle of great leaders like Peel, Disraeli, Salisbury and Baldwin, who had adapted the party. To achieve that, I wanted Conservative means to achieve progressive ends. Using prices and markets, and encouraging personal and corporate responsibility, could help our environment by cutting pollution and greenhouse gases. Stronger families and more rigorous school standards could help reduce inter-generational poverty. Trusting the professionals in our NHS, rather than smothering them with bureaucracy, could build a stronger health service.

The Conservative Party, in my view, had got into a rut of tired and easy thinking. We had a tendency to trot out the same old answers. Want social mobility? Open more grammar schools. Want lower crime? Put more bobbies on the beat. Want a more competitive economy? Just cut taxes.

We had another, even more profound, problem. People didn’t trust our motives. Whenever we suggested something, people seemed almost automatically to add their own mistrustful explanation of our motives. When we said, ‘Let’s reduce taxes,’ they added, ‘to help the rich’. When we said, ‘Let’s start up new schools,’ they added, ‘for your kids, not ours.’

Part of this was a hangover from the end of the last period of Conservative rule, when Tony Blair and New Labour had caricatured Conservatives as uncaring. But some of it was our own fault. It was part of what I called – or more accurately what Samantha called – the ‘man under the car bonnet’ syndrome. We approached every problem or issue with a mechanical, process-driven response rather than a more emotional, values-driven answer about the ends we were aiming to achieve.

At the same time as the new approach and new policies, I was determined that the Conservative Party should make its peace with the modern world. Our opposition to, or sometimes grudging acceptance of, a whole range of social reforms, from lowering the age of consent for gay men to positive action to close the gender pay gap, made us look and sound like a party that was stuck in the past, and didn’t like the modern country we aspired to govern.

I wanted the Conservative Party to be more liberal on these social issues. I felt passionately that morally it was the right thing to do, and I thought it would help us to get a hearing from some people who had written us off. It seemed to me an embarrassment, really just awful in every possible way, that someone who shared our values might be put off voting Conservative because they thought we disapproved of their sexuality, or looked down on their ethnicity, or didn’t want them to achieve because of their gender.

Part of the problem was our personnel. We were the oldest political party in the world – and we looked it. Just seventeen of the 198 Tory MPs elected in 2005 were women. That was an improvement of four. Since 1931.

Totally unacceptable. We were, after all, the party of the first woman MP to take her seat in the Commons. We gave the country its first female prime minister. Up and down Britain, women were among our finest councillors and our fiercest campaigners. But it just didn’t show on our green benches, which were, by and large, male, middle-aged, southern, wealthy and white.

By day four of the job I had appointed all my shadow ministers. I thought it was important to bring my leadership rivals into the fold, so David Davis and Liam Fox shadowed the home and defence departments. I thought I’d got a good mix, but I ended up with more people called David in the shadow cabinet (five) than women (four). There simply wasn’t the range from which to choose.

Come day seven I was at the Met Hotel in Leeds unveiling a plan to elect more women and ethnic minority MPs (of whom we had, shamefully, just two). It was imperative that we started to look more like the country we hoped to govern.

The candidates’ list was immediately frozen. A new Priority List of 150 candidates, people we thought the cream of the crop, and better reflecting the make-up of modern Britain, was drawn up from the larger main list. All associations in winnable seats would have to choose from this so-called ‘A-List’.

It caused uproar. Uproar so furious and so persistent that a year later I ended up agreeing that associations could pick their candidates from the full list, but half of the interviewees had to be women, thereby superseding the A-List.