Полная версия

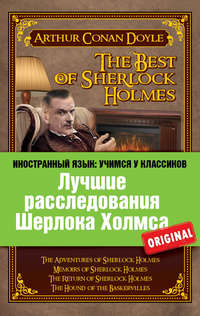

Приключения Шерлока Холмса / The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

Артур Конан Дойл / Arthur Conan Doyle

Приключения Шерлока Холмса / The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

© Глушенкова Е.В., Тамбовцева С.Г., адаптация текста, словарь

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2019

The Red-Headed League

I

I called on my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, one day in the autumn of last year and found him speaking to an elderly gentleman with fiery red hair.

“You could not have come at a better time[1], my dear Watson,” Holmes said.

“I was afraid that you were engaged.”

“So I am.”

“Then I can wait in the next room.”

“Not at all. This gentleman, Mr. Wilson, has been my partner and helper in many of my most successful cases, and I have no doubt that he will be of use to me in yours also.”

The gentleman half rose from his chair and nodded.

“I know, my dear Watson, that you share my love of all that is outside the routine of everyday life. You have shown it by the enthusiasm with which you chronicled so many of my adventures,” said Holmes.

“Your cases have been of the greatest interest to me,” I observed.

“Now, Mr. Jabez Wilson here has been good enough to call upon me this morning and go begin a story which promises to be one of the most unusual which I have listened to for some time. As far as I have heard, it is impossible for me to say whether this case is an example of crime or not, but events are certainly very unusual. Perhaps, Mr. Wilson, you would repeat your story. I ask you not only because my friend, Dr. Watson, has not heard the beginning but also because your story makes me anxious to hear every detail. As a rule, when I have heard some story, I am able to think of the thousands of other similar cases. But not now.”

The client, looking a little proud, took a newspaper from the pocket of his coat. As he glanced down the advertisement column, I took a good look at the man and tried, like my companion, to read what his dress or appearance could tell me.

I did not learn very much, however. Our visitor looked like a common British tradesman. There was nothing remarkable about the man except his blazing red head.

Sherlock Holmes saw my glances. “Except the facts that he has at some time worked with his hands, that he is a Freemason, that he has been in China, and that he has done a lot of writing lately, I can deduce nothing else.”

“How did you know all that, Mr. Holmes?” Mr. Jabez Wilson asked. “How did you know, for example, that I worked with my hands? It’s true, for I began as a carpenter.”

“Your hands, my dear sir. Your right hand is much larger than your left. You have worked with it, and the muscles are more developed.”

“Well, and the Freemasonry?”

“I won’t tell you how I read that, especially as,rather against the strict rules of your order, you use an arc-and-compass breastpin[2].”

“Ah, of course, I forgot that. But the writing?”

“Your right cuff is so shiny, and the left one has a patch near the elbow where you put it on the desk.”

“Well, but China?”

“The fish that you have tattooed on your hand could only be done in China. I have made a small study of tattoos.”

Mr. Jabez Wilson laughed. “Well, I never![3]” said he. “I thought at first that you had done something clever, but I see that there was nothing in it, after all.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

You could not have come at a better time – Вы пришли как нельзя более кстати

2

rather against the strict rules of your order, you use an arc-and-compass breastpin – вопреки строгим правилам своего ордена, вы носите булавку с изображением дуги и окружности (дуга и окружность – знаки масонов)

3

Well, I never! – Ни за что б не догадался!