Полная версия

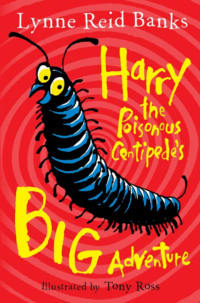

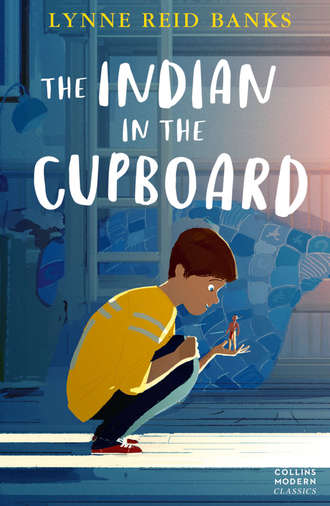

The Indian in the Cupboard

At the very best, the Indian must have passed a horrible day in that dark prison. Omri was dismayed at the thought of it. Why had he allowed himself to be drawn into that silly row at breakfast instead of slipping away and making sure the Indian was all right? The mere thought that he might be dead was frightening Omri sick. He ran all the way home, burst through the back door, and raced up the stairs without even saying hello to his mother.

He shut the door of his bedroom and fell on his knees beside the bedside table. With a hand that shook, he turned the key in the lock and opened the cupboard door.

The Indian lay there on the floor of the cupboard, stiff and stark. Too stiff! That was not a dead body. Omri picked it up. It was an ‘it’, not a ‘he’, any more.

The Indian was made of plastic again.

Omri knelt there, appalled – too appalled to move. He had killed his Indian, or done something awful to him. At the same time he had killed his dream – all the wonderful, exciting, secret games that had filled his imagination all day. But that was not the main horror. His Indian had been real – not a mere toy, but a person. And now here he lay in Omri’s hand – cold, stiff, lifeless. Somehow through Omri’s own fault.

How had it happened?

It never occurred to Omri now that he had imagined the whole incredible episode this morning. The Indian was in a completely different position from the one he had been in when Patrick gave him to Omri. Then he had been standing on one leg, as if doing a war-dance – knees bent, one moccasined foot raised, both elbows bent too and with one fist (with the knife in it) in the air. Now he lay flat, legs apart, arms at his sides. His eyes were closed. The knife was no longer a part of him. It lay separately on the floor of the cupboard.

Omri picked it up. The easiest way to do this, he found, was to wet his finger and press it down on the tiny knife, which stuck to it. It, too, was plastic, and could no more have pierced human skin than a twist of paper. Yet it had pierced Omri’s finger this morning – the little mark was still there. But this morning it had been a real knife.

Omri stroked the Indian with his finger. He felt a painful thickness in the back of his throat. The pain of sadness, disappointment, and a strange sort of guilt, burnt inside him as if he had swallowed a very hot potato which wouldn’t cool down. He let the tears come, and just knelt there and cried for about ten minutes.

Then he put the Indian back in the cupboard and locked the door because he couldn’t bear to look at him any longer.

That night at supper he couldn’t eat anything, and he couldn’t talk. His father touched his face and said it felt very hot. His mother took him upstairs and put him to bed and oddly enough he didn’t object. He didn’t know if he was ill or not, but he felt so bad he was quite glad to be made a fuss of. Not that that improved the basic situation, but it was some comfort.

“What is it, Omri? Tell me,” coaxed his mother. She stroked his hair and looked at him tenderly and questioningly, and he nearly told her everything, but then he suddenly rolled over on his face.

“Nothing. Really.”

She sighed, kissed him, and left the room, closing the door softly after her.

As soon as she had gone, he heard something. A scratching – a muttering – a definitely alive sound. Coming from the cupboard.

Omri snapped his bedside light on and stared wide-eyed at his own face in the mirror on the cupboard door. He stared at the key with its twisted ribbon. He listened to the sounds, now perfectly clear.

Trembling, he turned the key and there was the Indian, on the shelf this time, almost exactly level with Omri’s face. Alive again!

Again they stared at each other. Then Omri asked falteringly, “What happened to you?”

“Happen? Good sleep happen. Cold ground. Need blanket. Food. Fire.”

Omri gaped. Was the little man giving him orders? Undoubtedly he was! Because he waved his knife, now back in his hand, in an unmistakable way.

Omri was so happy he could scarcely speak.

“Okay – you stay there – I’ll get food – don’t worry,” he gasped as he scrambled out of bed.

He hurried downstairs, excited but thoughtful. What could it all mean? It was puzzling, but he didn’t bother worrying about it too much. His main concern was to get downstairs without his parents hearing him, get to the kitchen, find some food that would suit the Indian, and bring it back without anyone asking questions.

Fortunately his parents were in the living-room watching television, so he was able to tiptoe to the kitchen along the dark passage. Once there, he dared not turn on a light; but there was the fridge light and that was enough.

He surveyed the inside of the fridge. What did Indians eat? Meat, chiefly, he supposed – buffalo meat, rabbits, the sort of animals they could shoot on their prairies. Needless to say there was nothing like that.

Biscuits, jam, peanut butter, that kind of thing was no problem, but somehow Omri felt sure these were not Indian foods. Suddenly his searching eyes fell on an open tin of sweetcorn. He found a paper plate in the drawer where the picnic stuff lived, and took a good teaspoon of corn. Then he broke off a crusty corner of bread. Then he thought of some cheese. And what about a drink? Milk? Surely, Indian braves did not drink milk? They usually drank something called ‘fire-water’ in films, which was presumably a hot drink, and Omri dared not heat anything. Ordinary non-fire water would have to do, unless … What about some Coke? That was an American drink. Luckily there was a bit in a big bottle left over from the birthday party, so he took that. He did wish there were some cold meat, but there just wasn’t.

Clutching the Coke bottle by the neck in one hand and the paper plate in the other, Omri sneaked back upstairs with fast-beating heart. All was just as he had left it, except that the Indian was sitting on the edge of the shelf dangling his legs and trying to sharpen his knife on the metal. He jumped up as soon as he saw Omri.

“Food?” he asked eagerly.

“Yes, but I don’t know if it’s what you like.”

“I like. Give, quick!”

But Omri wanted to arrange things a little. He took a pair of scissors and cut a small circle out of the paper plate. On this he put a crumb of bread, another of cheese, and one kernel of the sweetcorn. He handed this offering to the Indian, who backed off, looking at the food with hungry eyes but trying to keep watch on Omri at the same time.

“Not touch! You touch, use knife!” he warned.

“All right, I promise not to. Now you can eat.”

Very cautiously the Indian sat down, this time cross-legged on the shelf. At first he tried to eat with his left hand keeping the knife at the ready in his right, but he was so hungry he soon abandoned this effort, laid the knife close at his side and, grabbing the bread in one hand and the little crumb of cheese in the other, he began to tear at them ravenously.

When these two apparently familiar foods had taken the edge off his appetite, he turned his attention to the single kernel of corn.

“What?” he asked suspiciously.

“Corn. Like you have—” Omri hesitated. “Where you come from,” he said.

It was a shot in the dark. He didn’t know if the Indian ‘came from’ anywhere, but he meant to find out. The Indian grunted, turning the corn about in both hands, for it was half as big as his head. He smelt it. A great grin spread over his face. He nibbled it. The grin grew wider. But then he held it away and looked again, and the grin vanished.

“Too big,” he said. “Like you,” he added accusingly.

“Eat it. It’s the same stuff.”

The Indian took a bite. He still looked very suspicious, but he ate and ate. He couldn’t finish it, but he evidently liked it.

“Give meat,” he said finally.

“I’m sorry, I can’t find any tonight, but I’ll get you some tomorrow,” said Omri.

After another grunt, the Indian said, “Drink!”

Omri had been waiting for this. From the box where he kept his Action Man things he had brought a plastic mug. It was much too big for the Indian but it was the best he could do. Into it, with extreme care, he now poured a minute amount of Coke from the huge bottle.

He handed it to the Indian, who had to hold it with both hands and still almost dropped it.

“What?” he barked, after smelling it.

“Coca-Cola,” said Omri, enthusiastically pouring some for himself into a toothmug.

“Fire-water?”

“No, it’s cold. But you’ll like it.”

The Indian sipped, swallowed, gulped. Gulped again. Grinned.

“Good?” asked Omri.

“Good!” said the Indian.

“Cheers!” said Omri, raising his toothmug as he’d seen his parents do when they were having a drink together.

“What cheers?”

“I don’t know!” said Omri, feeling excessively happy, and drank. His Indian – eating and drinking! He was real, a real, flesh-and-blood person! It was too marvellous. Omri felt he might die of delight.

“Do you feel better now?” he asked.

“I better. You not better,” said the Indian. “You still big. You stop eat. Get right size.”

Omri laughed aloud, then stopped himself hastily.

“It’s time to sleep,” he said.

“Not now. Big light. Sleep when light go.”

“I can make the light go,” said Omri, and switched out his bedside lamp.

In the darkness came a thin cry of astonishment and fear. Omri switched it on again.

The Indian was now gazing at him with something more than respect – a sort of awe.

“You spirit?” he asked in a whisper.

“No,” said Omri. “And this isn’t the sun. It’s a lamp. Don’t you have lamps?”

The Indian peered where he was pointing. “That lamp?” he asked unbelievingly. “Much big lamp. Need much oil.”

“But this isn’t an oil lamp. It works by electricity.”

“Magic?”

“No, electricity. But speaking of magic – how did you get here?”

The Indian looked at him steadily out of his black eyes.

“You not know?”

“No, I don’t. You were a toy. Then I put you in the cupboard and locked the door. When I opened it, you were real. Then I locked it again, and you went back to being plastic. Then—”

He stopped sharply. Wait! What if – he thought furiously. It was possible! In which case …

“Listen,” he said excitedly. “I want you to come out of there. I’ll find you a much more comfortable place. You said you were cold. I’ll make you a proper tepee—”

“Tepee!” the Indian shouted. “I not live tepee! I live longhouse!”

Omri was so eager to test his theory about the cupboard that he was impatient. “You’ll have to make do with a tepee tonight,” he said. Hastily he opened a drawer and took out a biscuit tin full of little plastic people. Somewhere in here was a plastic tepee … “Ah, here!” He pounced on it – a small, pinkish, cone-shaped object with designs rather badly painted on its plastic sides. “Will this do?”

He put it on the shelf beside the Indian, who looked at it with the utmost scorn.

“This – tepee?” he said. He touched its plastic side and made a face. He pushed it with both hands – it slid along the shelf. He bent and peered in through the triangular opening. Then he actually spat on the ground, or rather, on the shelf.

“Oh,” said Omri, rather crestfallen. “You mean it’s not good enough.”

“Not want toy,” said the Indian, and turned his back, folding both arms across his chest with an air of finality.

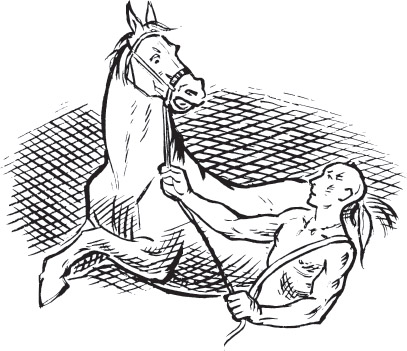

Omri saw his chance. With one quick movement he had picked up the Indian by the waist between his thumb and forefinger. In doing this he pinned the knife, which was in the Indian’s belt, firmly to his side. The dangling Indian twisted, writhed, kicked, made a number of ferocious and hideous faces – but beyond that he was helpless and he evidently knew it, for after a few moments he decided it was more dignified to stop struggling. Instead, he folded his tiny arms across his chest once again, put his head back, and stared with proud defiance at Omri’s face, which was now level with his own.

For Omri, the feeling of holding this little creature in his fingers was very strange and wonderful. If he had had any doubts that the Indian was truly alive, the sensation he had now would have put them to rest. His body was heavier now, warm and firm and full of life – through Omri’s thumb, on the Indian’s left side, he could feel his heart beating wildly, like a bird’s.

Although the Indian felt strong, Omri could sense how fragile he was, how easily an extra squeeze could injure him. He would have liked to feel him all over, his tiny arms and legs, his hair, his ears, almost too small to see – yet when he saw how the Indian, who was altogether in his power, faced him boldly and hid his fear, he lost all desire to handle him; he felt it was cruel, and insulting to the Indian, who was no longer his plaything but a person who had to be respected.

Omri put him down gently on the chest-of-drawers where the cupboard stood. Then he crouched down till his face was again level with the Indian’s.

“Sorry I did that,” he said.

The Indian, breathing heavily and with his arms still folded, said nothing, but stared haughtily at him, as if nothing he did could affect him in any way.

“What’s your name?” asked Omri.

“Little Bull,” said the Indian, pointing proudly to himself. “Iroquois brave. Son of Chief. You son of Chief?” he shot at Omri fiercely.

“No,” said Omri humbly.

“Hm!” snorted Little Bull with a superior look. “Name?”

Omri told him. “Now we must find you another place to sleep – outside the cupboard. Surely you sleep in tepees sometimes?”

“Never,” said Little Bull firmly.

“I’ve never heard of an Indian who didn’t,” said Omri with equal firmness. “You’ll have to tonight, anyway.”

“Not this,” said the Indian. “This no good. And fire. I want fire.”

“I can’t light a real fire in here. But I’ll make you a tepee. It won’t be very good, but I promise you a better one tomorrow.”

He looked round. It was good, he thought, that he never put anything away. Now everything he needed was strewn about the floor and on tables and shelves, ready to hand.

Starting with some pick-up-sticks and a bit of string, he made a sort of cone-shape, tied at the top. Around this he draped, first a handkerchief, and then, when that didn’t seem firm enough, a bit of old felt from a hat that had been in the dressing-up crate. It was fawn coloured, fortunately, and looked rather like animal hide. In fact, when it was pinned together at the back with a couple of safety-pins and a slit cut for an entrance, the whole thing looked pretty good, especially with the poles sticking up through a hole in the top.

Omri stood it up carefully on the chest-of-drawers and anxiously awaited Little Bull’s verdict. The Indian walked round it four times slowly, went down on hands and knees and crawled in through the flap, came out again after a minute, tugged at the felt, stood back to look at the poles, and finally gave a fairly satisfied grunt. However, he wasn’t going to pass it without any criticism at all.

“No pictures,” he growled. “If tepee, then need pictures.”

“I don’t know how to do them,” said Omri.

“I know. You give colours. I make.”

“Tomorrow,” said Omri, who, despite himself, was beginning to feel very sleepy.

“Blanket?”

Omri fished out one of the Action Man’s sleeping-rolls.

“No good. No keep out wind.”

Omri started to object that there was no wind in his bedroom, but then he decided it was easier to cut up a square out of one of his old sweaters, so he did that. It was a red one with a stripe round the bottom and even Little Bull couldn’t hide his approval as he held it up, then wrapped it round himself.

“Good. Warm. I sleep now.”

He dropped on his knees and crawled into the tent. After a moment he stuck his head out.

“Tomorrow talk. You give Little Bull meat – fire – paint – much things.” He scowled fiercely up at Omri. “Good?”

“Good,” said Omri, and indeed nothing in his life had ever seemed so full of promise.

Chapter Three

THIRTY SCALPS

WITHIN A FEW minutes, loud snores – well, not loud, but loud for the Indian – began to come out of the tepee, but Omri, sleepy as he was himself, was not quite ready for bed. He had an experiment to do.

As far as he had figured it out so far, the cupboard, or the key, or both together, brought plastic things to life, or if they were already alive, turned them into plastic. There were a lot of questions to be answered, though. Did it only work with plastic? Would, say, wooden or metal figures also come to life if shut up in the cupboard? How long did they have to stay in there for the magic to work? Overnight? Or did it happen straight away?

And another thing – what about objects? The Indian’s clothes, his feather, his knife, all had become real. Was this just because they were part of the original plastic figure? If he put – well, anything you like, the despised plastic tepee for instance, into the cupboard and locked the door, would that be real in the morning? And what would happen to a real object, if he put that in?

He decided to make a double trial.

He stood the plastic Indian tent on the shelf of the cupboard. Beside it he put a Matchbox car. Then he closed the cupboard door. He didn’t lock it. He counted slowly to ten.

Then he opened the door.

Nothing had happened.

He closed the door again, and this time locked it with his great-grandmother’s key. He decided to give it a bit longer this time, and while he was waiting he lay down in bed. He began counting to ten slowly. He got roughly as far as five before he fell asleep.

He was woken at dawn by Little Bull bawling at him.

The Indian was standing outside the felt tepee on the edge of the table, his hands cupped to his mouth as if shouting across a measureless canyon. As soon as Omri’s eyes opened, the Indian shouted:

“Day come! Why you still sleep? Time eat – hunt – fight – make painting!”

Omri leapt up. He cried, “Wait” – and almost wrenched the cupboard open.

There on the shelf stood a small tepee made of real leather. Even the stitches on it were real. The poles were twigs, tied together with a strip of hide. The designs were real Indian symbols, put on with bright dyes.

The car was still a toy car made of metal, no more real than it had ever been.

“It works,” breathed Omri. And then he caught his breath. “Little Bull!” he shouted. “It works, it works! I can make any plastic toy I like come alive, come real! It’s real magic, don’t you understand? Magic!”

The Indian stood calmly with folded arms, evidently disapproving of this display of excitement.

“So? Magic. The spirits work much magic. No need wake dead with howls like coyote.”

Omri hastily pulled himself together. Never mind the dead, it was his parents he must take care not to wake. He picked up the new tepee and set it down beside the one he had made the night before.

“Here’s the good one I promised you,” he said.

Little Bull examined it carefully. “No good,” he said at last.

“What? Why not?”

“Good tepee, but no good Iroquois brave. See?” He pointed to the painted symbols. “Not Iroquois signs. Algonquin. Enemy. Little Bull sleep there, Iroquois spirits angry.”

“Oh,” said Omri, disappointed.

“Little Bull like Omri tepee. Need paint. Make strong pictures – Iroquois signs. Please spirits of ancestors.”

Omri’s disappointment melted into intense pride. He had made a tepee which satisfied his Indian! “It’s not finished,” he said. “I’ll take it to school and finish it in my handicrafts lesson. I’ll take out the pins and sew it up properly. Then when I come home I’ll give you poster-paints and you can paint your symbols.”

“I paint. But must have longhouse. Tepee no good for Iroquois.”

“Just for now?”

Little Bull scowled. “Yes,” he said. “But very short. Now eat.”

“Er … Yes. What do you like to eat in the mornings?”

“Meat,” said the Indian immediately.

“Wouldn’t you like some bread and cheese?”

“Meat.”

“Or corn? Or some egg?”

The Indian folded his arms uncompromisingly across his chest.

“Meat,” said Omri with a sigh. “Yes. Well, I’ll have to see what I can do. In the meantime, I think I’d better put you down on the ground.”

“Not on ground now?”

“No. You’re high above the ground. Go to the edge and look – but don’t fall!”

The Indian took no chances. Lying on his stomach he crawled, commando-fashion, to the edge of the chest-of-drawers and peered over.

“Big mountain,” he commented at last.

“Well …” But it seemed too difficult to explain. “May I lift you down?”

Little Bull stood up and looked at Omri measuringly. “Not hold tight?” he asked.

“No. I won’t hold you at all. You can ride in my hand.”

He laid his hand palm up next to Little Bull, who, after only a moment’s hesitation, stepped on to it and, for greater stability, sat down cross-legged. Omri gently transported him to the floor. The Indian rose lithely to his feet and jumped off on to the grey carpet.

At once he began looking about with suspicion. He dropped to his knees, felt the carpet and smelt it.

“Not ground,” he said. “Blanket.”

“Little Bull, look up.”

He obeyed, narrowing his eyes and peering.

“Do you see the sky? Or the sun?”

The Indian shook his head, puzzled.

“That’s because we’re not outdoors. We’re in a room, in a house. A house big enough for people my size. You’re not even in America. You’re in England.”

The Indian’s face lit up. “English good! Iroquois fight with English against French!”

“Really?” asked Omri, wishing he had read more. “Did you fight?”

“Fight? Little Bull fight like mountain lion! Take many scalps.”

Scalps? Omri swallowed. “How many?”

Little Bull proudly held up all ten fingers. Then he closed his fists, opening them again with another lot of ten, and another.

“I don’t believe you killed so many people!” said Omri, shocked.

“Little Bull not lie. Great hunter. Great fighter. How show him son of Chief without many scalps?”

“Any white ones?” Omri ventured to ask.

“Some. French. Not take English scalps. Englishmen friends to Iroquois. Help Indian fight Algonquin enemy.”

Omri stared at him. He suddenly wanted to get away. “I’ll go and get you some – meat,” he said in a choking voice.

He went out of his room, closing the bedroom door behind him.

For a moment he did not move, but leant back against the door. He was sweating slightly. This was a bit more than he had bargained for!

Not only was his Indian no mere toy come to life; he was a real person, somehow magicked out of the past of over two hundred years ago. He was also a savage. It occurred to Omri for the first time that his idea of Red Indians, taken entirely from Western films, had been somehow false. After all, those had all been actors playing Indians, and afterwards wiping their war-paint off and going home for their dinners, not in tepees but in houses like his. Civilized men, pretending to be primitive, pretending to be cruel …