Полная версия

Hidden Hunter-Gatherers of Indian Ocean. With appendix

A number of the Veddahs were politically organized in the 16th century and that one of the most important of their chiefs, described in a contemporary manuscript as “Panikki”, was appointed to the high office of Bandara Mudiyanse. It is recorded that Panniki the Veddah caught elephants and took them to the king (Mesuruer 1886).

The Wanniyala-aetto can be classified as sedentary people, as they generally stay at one place for several years. Normally the group moves together and the new site is located quite near the old one.

Seligmans (1911) give the information about the mobility of Veddah. Their residental moves per year are 3 times, average distance is 11,2 km (with total distance of 36,3 km). Logistical mobility is zero days and primary biomass is 17,2 kg per square meter. Total area of mobility is 41 square kilometers.

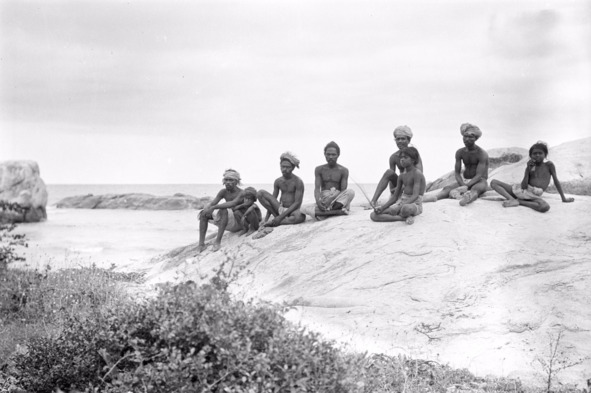

COASTAL VEDDAHS

The Veddah community in the east, often referred to as “Muhudu Veddah” or “Veddahs of the sea”, reside mainly in the Districts of Trincomalee and Batticaloa. Despite being intrinsically connected to the “original inhabitants of the land”, this community bears very little resemblance to the original Veddahs. The Veddahs themselves have a belief that they migrated from the inlands, being driven from their native “Sabaragamuwa” during the 17th century.

The Coastal Veddahs are often referred to as “Vardar”, “Vardaa” or “Vedar”. They are also referred to as “Palaya aalkal” (“ancient people”), a term ethnic Tamils fall back to when referring to a Veddah. Veddahs themselves prefer referring to them as “Vedar”, “Vedar Vellar” or just simply “Veddahs”. Canagaratnam considered the Vedar as a separate caste among the Tamil community itself (Canagaratnam 1921).

The title “Vellalar” is associated with the Tamil caste system prevalent in the north and the east. According to the caste hierarchical system, the “Vellalar” are an elite caste, thereby they receive privileges that are not associated with those of the lower castes. The “Vellalar” caste represents farmers, who are considered the highest of all castes apart from the Brahmins in the north of the country. This linkage with the title of “Vellalar” has helped the Veddah to shun his natural identity resulting in some acceptance within modern society. However, upon close inspection one would find out that this term has not been associated with Veddahs of the previous generation.

The older generation of Veddahs, despite not being able to give a clear date or place of their arrival in the coast, were of the opinion that their forefathers migrated to the coast of the country from a place with the name of “Gala” (“stone”). Taking the above into consideration, we can assume that these Veddahs migrated from either Dimbulagala or Nilgala, habitats situated close to the Batticaloa District. The Coast Veddahs do not know when they came or how they came, but they say that long ago their ancestors came from Gala, far beyond the hills to the west. They also sometimes say they came from Kukulugam near the Verukal, other suppose it to be somewhere far away.

Seligmanns (1911) suggested that the Coastal Veddahs and the Veddahs from Dimbulagala share certain similarities, including affiliation to the “Aembalawa” clan and this is used as a tool to evidence the relationships between the Veddahs of Dimbulagala and the Coastal Veddahs, thereby refuting the claim that they were in fact driven away from Sabaragamuwa Province in the 17th century.

Seligmanns wrote that “The Coast Veddahs do not know when they came or how they came, but they say that long ago their ancestors came from the Gala, far beyond the hills to the west. They also sometimes say they came from ‘Kukulu-gammaeda’ and spread out along the coast. Some say this is near Verukal; others suppose it to be somewhere far away” (ibid.).

When due recognition is given to empirical data it can be deduced that the origins of the Coastal Veddahs can be traced back to the 13th and 14th centuries. During that period, ethnic Sinhalese dominated the dwellings of Batticaloa and Hugh Neville’s research shows a presence of Coastal Veddahs during that time (Neville 1887). But Seligmanns stated (1911) that the Coastal Veddah settlements was limited to the north of Batticaloa. According to his discovery, the “Nadukadu” record goes on to state that when Mudliyar Rajapakshe visits Batticaloa, he brings with him two Veddahs akin to modern day bodyguards. The reason was his fear of attack from another Veddah clan, which resided in an area then known as “Palwekam”. There is also a record of the visit of King Senarath to the eastern coast. During this visit it is said that the Veddah of the “Vegoda” clan played the role of “obedient servant” to the king (Neville 1987).

During the Dutch rule of the island (1658—1798), Francois Valentine prepared a map of Ceylon (1796), titled “New Katt Van Het Eyland Ceylan” and consisted of an area in the east coast reaching up to modern day Mulaithivu demarcated as Coastal Veddah territory. There are certain records of the Dutch using Veddahs as soldiers and slaves (Goens 1974).

Some Coastal Veddahs have no distinct features that would immediately distinguish them from village Tamils, they speak the local dialects and do not possess any knowledge of the Veddah language (de Silva 1972). Unlike many indigenous groups, the Veddahs are proud of their culture and heritage and seek to preserve it unless circumstances are clearly unfavorable, hence the integration can be attributed to the natural evolution of the Veddahs, rather than any external factor. Many of the Veddahs of the older generation were proud of the fact that they were in fact Veddahs and referred to themselves as “Vardar”. However, the younger generation seems less inclined to acknowledge the essence of their forefathers and preferred to call themselves Tamils as opposed to Vardars. Very few old men know the names of some of the Veddah warige.

The folk that we consider as Coastal Veddahs also dislike being identified with the indigenous people. This can be mainly attributed to the caste hierarchy prevalent in the eastern and northern regions of the country. The Tamils lay a lot of emphasis on the caste of an individual and to modern days certain practices which discriminate individuals according to their caste are prevalent. The Veddah community is considered the lowest of the regional castes and is shunned by persons of higher castes. As a result, there has been a tremendous loss of heritage and roots for the Coastal Veddah people.

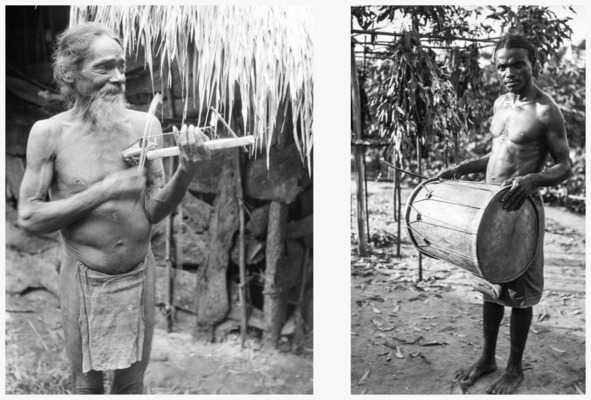

The Coast Veddahs are expert fishermen and make and use of various forms of nets including a cast net. They also spear and shoot fish, using a bifid iron spear-head, which they have adopted from the Tamils. For shooting fish, they use the usual Veddah bow, but the arrow has become a harpoon with a shaft as long as the bow into which the iron with its running line fits loosely (Storey 1907).

The ancestors of the current community were Veddah hunters with the bow and arrow and other traditional weapons. Despite the non use of traditional weapons, the modern days Veddahs don’t seem to have forgotten their ancestral customs – they have hunter dogs and use them to hunt animals such as monitors and rabbits, sometimes wild boar, killing it by spears.

The Verdars are darker, taller and more stoutly built than the inland Veddah (“Wanniyala-aetto”). Coastal Veddahs build comfortable huts in small clearings, usually within a mile of the sea. They cultivate maize and pumpkins round their houses and in patches of clearings in the surrounding jungles. They have plenty of pots, baskets and fishing gear. Their mode of life differs but little from that of the poor and low caste Tamils who are their neighbours. The religion of the Coast Veddahs is strongly tinged with Tamil customs and beliefs.

Some of the Coast Veddahs know the names of the warige to which they belong, and a few know the names of some important warige of the Veddas inland. “Uru” warige appears to be the clan to which most of the Coast Veddahs who remembered their ancestral warige belonged, very few stated that they belonged to “Ogatam”, “Kavatam”, “Umata” (“Umatam”), “Aembalaneduwe” and “Aembala” warige (the last one is probably the same as the inland “Aembala” warige). At the time of Seligmanns’ research very few can remember “Morane” warige and fewer know “Unapane” (Seligmann 1911).

AHIKUNTIKA

Very interesting people are still living today in the Eastern part of the country. This is “Kuravar” (in Tamil), so-called “Sri Lankan gypsies”. They are known as “Ahikuntika” in Sinhala.

The Ahikuntikas are mostly confined to the generally arid parts of the north central and eastern parts of the island. They speak Telugu language and could be descendants of the “Kuruvar” people of Andhra Pradesh.

One of the earliest references made by a European was by Phillip Baldaeus, who wrote “among the inhabitants of the coast of Coromandel, and the Cingalese and Malabars are certain follows who possess the art of making serpents stand upright and dance before them which they perform by enchanting songs” (Baldaeus 1992).

Emerson Tennett in his “Natural History of Ceylon” described the use of a “snake stone” used by snake charmers (Tennett 1999).

John Davy in his record of his residence in Sri Lanka wrote: “during my residence in Ceylon, by the death of one of these performers, when his audience had provoked to attempt some unaccustomed familiarity with the cobra, it bit him on the wrist, and he expired the same evening” (Davy 2005).

J.Bennett provided an excellent description of an early 19th century performance by an iterant snake charming due from India, and a cautionary tale on buying cobras for those few, daring souls (such as himself) who wished to keep them as a pets (Bennett 2009).

The Ahikuntikayas were never accustomed to have permanent shelters. They built their huts usually on elevated grounds but necessarily near a river bank or a tank bund. The roof was always constructed either in the shape if a triangle or in a curvature with palm leaves or grass. Since each family needed a hut, the number of huts in a “colony” was always determined by the number of families moving in a given caravan. Such a collection of Ahikuntikaya shelters was called a “Kuppayama” which in its traditional Sinhala meaning is “a colony of social outcasts”.

These shelters always betrayed their semi-permanent character and had limited utensils. These included a knife (“maskan”), grinder (“rolu”), basin (“traale”), coconut scraper (“iraman”), pots (“kadawa”), saucepans (“kunda”) which were essential in every shelter. Dogs and donkeys also accompanied them in every journey. Nowadays this is rare due to the constraints of moving such animals through modern settlements even in rural settings (Widyalankara 2015).

The Ahikuntikas observe a custom of holding an annual conclave which is called “Varigasabha” (“meeting of clans”). Future plans of the community, nuptial bonds between clans, common problems encountered in maintaining their customs and livelihoods were the main items of concern.

There are also different sub-communities (“kula”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.