Полная версия

Hidden Hunter-Gatherers of Indian Ocean. With appendix

The earliest account (400 A.D.) about the Yakkas written by a foreigner, probably Palladius, is in “De Moribus Brachmanorum”. It mentions how a Theban traveler, who arrived to Ceylon in an Indian trading vessel from Axum, whilst travelling inland suddenly came upon the Besadae. He says that “these people are by far the smallest and weakest, they live in rock caves and know how to climb over the intricately massed rocks and thus gather pepper from the bushes” (Spittel 1957).

The Chinese traveler Yueng Chaing (700 A.D.) speaks of the Yakkahs as having retired to the South-East part of the island. The Arabic traveler Al-Beruni (1100 A.D.) describes the silent trade with savage “Ginn”. During the time of Parakramabahu (1163 A.D.) the “Kiratas” are mentioned thus: “There he sent his train of hunters, robbers and the like who were skilled in wandering by night in the wilderness of forest and mountain” (Cūlavamsa 1929). Who were the Yakkahs and what was their affinity to the Veddahs? The hunters referred to were probably Veddahs who were in the King’s retinue. “Kirata”, meaning “hunter”, is also used in Sanskrit to describe savage mountain tribe.

In 1675 Rijklof Van Goens, the Dutch Governor of Ceylon, gave a full description of the Veddas thus

“…A large number of Veddas or Beddas of Wellassa have been brought under. They should be carefully treated, neither too harshly nor too kindly. They should be made to work… fairly savage, they are brave fellows in the hunt and expert bowmen” (Spittel 1957).

Robert Knox (Knox 1681) mentioned that

“of these Natives there be two sorts wild and tame… For as in these woods there are wild beasts so wild men also. The land of Bintan is all covered with mighty woods filled with abundance of deer. In this Land are many of these wild men; they call themselves Vaddahs, dwelling near no other inhabitants. They speak the Chingulayes language. They kill deer, and dry the flesh over the fire, and the people of the country come and buy it of them. They never till any ground for corn, their food being only flesh. They are very expert with their bows. They have a little axe, which they stick by their sides, to cut honey out of hollow trees… They have no towns nor houses, only live by the waters under a tree, with some bought cut and laid about them, to give notice when any wild beasts come near, which they may hear by their rustling and trampling upon them”.

There is an information in Seligmanns’ book that Sinhalese of Vedirata told them that Veddah chiefs pay and offering to royal household in Kandy of honey, wax, and king might also invite their presence on special occasions. Each “Wanniya” bring with him a ceremonial fanlike ornament (which was still used by the Sinhalese chiefs) called “awupata” (literally “fan”), with an ornament made of wood or ivory on the top called “koraṇḍuwa” or “kota” (Seligmann 1911). Before the introducing of money, the barter was common. Trading places called “wadia” near the caves, but out of sight of them, under a tree or rock, were used for bartering.

There are four traditional occupations of the “Wanniyala-aetto”: hunting and gathering, slash-and-burn cultivation and livestock herding, all combined with temporary employment as unskilled labors (digging wells or ditches, carrying soil, breaking stone or road construction).

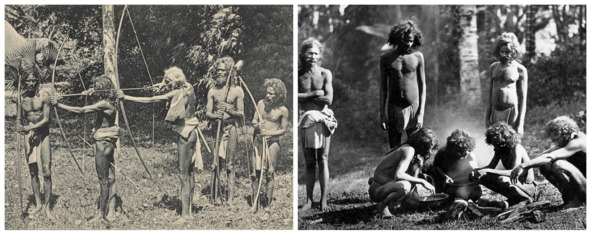

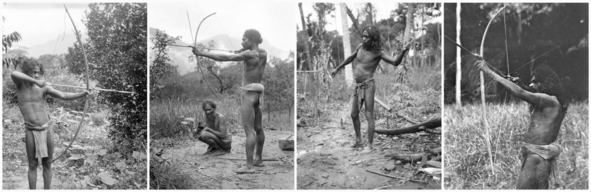

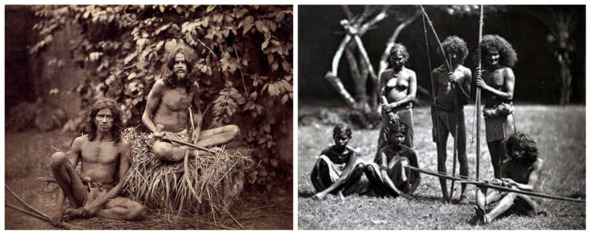

Every Veddah man carried a bow and arrows (“tudaāi” – a number of arrows carried). For fletching used the feathers of the forest eagle owl (Huhua nipalensis), hawk-eagle (Spiraetus nipalensis kelaartii) and crested honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus ruficollis) (Stegeborn 1993), but also the feathers of peacocks, herons and hawks were used (Bailey 1863). The bow and arrows made up the characteristic weapon of the Veddahs. The bow was of the simple type – the double bend bow or the cross bow was not known to the Veddahs. The bows were made of peeled and shaved saplings of the “kobbe” tree (Allophylus cobbe) and bow-strings were made from the inner cortex of the “aralui” bark (Terminalia chebula). Arrow shafts must be straight and light so welan wood perfectly suited this purpose. Today the bow and arrows are almost only used for instructing and training young boys.

The Veddahs have learnt the use of the spring noose, dead fall and trap gun (Spittel 1957). Fish were caught and eaten when other food is scarce. The commonest method of catching the fish was to bale the water. A section of the stream was banked and the fish were stupefied by muddying or poisoning the water. The poison-bearing material was crushed and thrown into the pool or banked waterways. The water was stirred and as it got stained the fish become restless and stupefied. The fish leaped on the bank or fleet on the surface with belly upwards. Then it was easily collected (Spittel 1957). The fish could have also been dried over a trestle.

Sling, bow and arrows

According to Knox, those Veddah who need a new arrow, should bring a deer flesh or honey to the blacksmith, and also a leaf “cut in the form they will have their arrows made”. Knox described the traditional method of preserving flesh: by putting flesh with honey in the hollow of the tree and stopping the hollow by the clay. Very interesting is the description of customs of giving hunting dogs with young girls while marriages, and traditions of leaving homes by Sinhalese to live with Veddah (Knox 1681). The steel heads of the axes were obtained from the local blacksmiths by bartering skins, honey and meat. So are the other steel implements such as arrow-heads, areca-nut cutters and strike-a-light obtained. No other cutting implement or knife was used.

Near the hunting trap

For trapping they employed poles, sticks, twigs and strings made from the bark of the “riti” tree (Antiaris innoxia). In 20th century the Wanniyala-aetto changed their hunting tools to muzzle-loaders, shutguns and knives, but still used traditional axes.

The summer dry season is the principal collecting time. Both women and men gathered. After a rain, mushrooms spread in the old chenas. Medicinal herbs are also collected by the family of the medicine-man. Only men hunted and trapped large animals; women snared small animals and birds. The spotted deer, the Asian sambhur deer (Cervus unicolor) and wild boar were favorite game animals. Monkeys, langurs, mouse deer, pangolins, mangoose, hares, monitor lizards were also taken (Stegeborn 1999). Wanniyala-aetto were not found of eating birds, neither wild nor domesticated. Notes (1901) mentioned that Wanniyala-aetto didn’t eat buffalo and porcupine, but Wiweca Stegeborn (1993) named porcupine in the list of the game they hunted. No one hunted elephants. Monkey skin was also used to make a betel pouch.

Once an animal was killed, there were many chores to accomplish. A large animal was chopped up and smoked to lighten the burden of carrying it back to the hamlet. Firewood needed to be collected, smoking tables needed to be constructed and the meat was sliced into thin strips. With a large animal such as sambhur, the butchering and smoking might have taken twelve to eighteen hours.

Sometimes close collaboration is required by several men to butcher and carry the game back home. Large parties formed if the resources were plentiful as for example when the trees were heavy with “mora” (Niphelium longana) and tamarind berries (Dialium ovideum).

In the dry season, tree blossom and bees are active. The men searched for honey and beeswax, principal items of trade. The favorite bees were the “Apis indica” and the “Apis dorsata”. Wanniyala-aetto had secret places, passed from generation to generation, where they went to collect honey and beeswax. They also collected barks (which used to make cloth bags), sap and resins, while women gathered medicinal herbs, leaves, berries and nuts, most of which were sold to Sinhalese pedlars. Honey was also a useful medium for barter with the Moor traders and the neighboring villagers. The Sinhalese use it for medical purposes (Wijesekera 1964). The Veddahs eat the larvae and wax with the honey.

Digging eatable roots

No one is denied access to the natural resources on which all of them depend. No individual owns the forest. The families have equal rights to acquire these resources but each extended family knows its traditional hunting and “chena” circles and those are respected by others. Hunting grounds were strongly marked for every “warige” (clan), and the intruder would be killed and his liver taken, then the piece dried in the sun in a secret place was keeping in betel pouch. No other part of the dead man had been used and such a custom gave rise neither to warfare not to vendettas (Tennent 1860). The Wanniyala-aetto do not have the economic base to sustain a military effort for a protracted period. They are not accustomed to being organized that can be mobilize or draft warriors, direct them and give them reasons to fight, so a war can’t be conducted. There is not much to gain by plundering other Wanniyala-aetto people. There are no standard items of exchange that serve as capital or as valuables, and the material wealth of these hunters and gatherers is inconsiderable.

Males started to learn the skills of tracking and hunting around the age of ten to eleven years. A boy was given his first bow as soon as he has been able to hold one (around three years old). This type of bow was basically built on the same principle as the slingshot; it was strung with two cords, connected at the centre by a one centimeter wide woven fiber mat. A small stone was placed in the mat and firmly gripped between the thumb and the fingers. When they were eight to nine years old they collected honey together. At the age of eleven, twelve or thirteen years, a boy started to accompany his father on one-day hunting trips.

Wanniyala-aetto hunter with a digging stick, axe and two killed monitor lizards

There are no full-time specialists among the Wanniyala-aetto. The shaman, for example, only exercise his craft upon request – he passes his days like everyone else. His sons may or may not become a shaman – no one insists, if the sons are not interested in that. Seligmanns stated (1911) that sometimes at Village Veddahs (i.e. in Horaborawewa) the shaman could be the local Sinhalese headman, who stated the same “yaku” (spirits) were invoked by Veddahs and Sinhalese alike. In the village of Lindegala (neighborhood of Kallodi) was a “vederale” (medicine man), who was tall and has represented typical Sinhalese features, also he was employed by the Sinhalese for miles round. Wanniyala-aetto society was egalitarian. There was no common authority ruling over all; nobody from one compound could have exercised power in another. All labor in this society was valued equally. Three activities involve special skills practiced only by men: shamanism, healing and drumming.

There are no headmen or chiefs – leadership is based on recognized ability in different activities. Fulltime specialists and differentiated economic, political and religious institutions are alien to the Wanniyala-aetto. They do have shamans and people who know about herbal medicines, but other than the family itself is the group that fulfill all roles. The only consistent supremacy of any kind is that of a person of higher age and wisdom who might lead a ceremony, a person with a special skill may be asked to give advice or occasionally to lead, a hunter with sharper eyesight may walk some steps ahead of the others when searching for game.

Justice as employed by the Wanniyala-aetto is based on common understanding. Relatives and friends of the accuser and the accused discuss and negotiate with each other until an acceptable agreement or a compromise is made. Direct confrontation between the parties is not the rule. After the consensus the two main protagonists meet directly to clarify and to confirm what they have agreed to, mediated by their delegated relatives and friends. This is usually accomplished in a polite and cordial manner, which prescribes a symbolic contribution of betel by the accuser to the family of the defendant, who in turn is invited to share a meal with them. Both parties find it equally important to maintain good relations and peace between the hamlets (Stegeborn 1993).

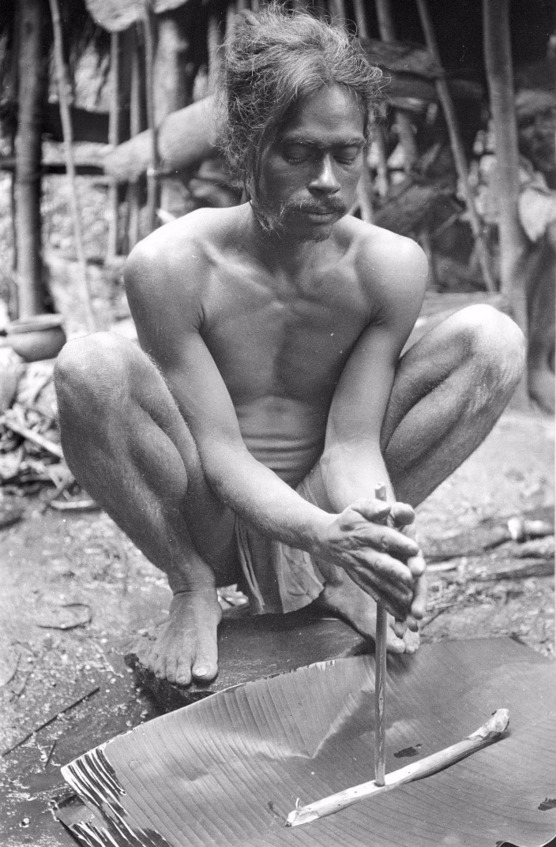

Drilling a fire

Among the Village Veddahs the women wore ivory studs in bored ears. Fire was obtained from two pieces of wood by drilling. The method of making fire by stone and a piece of metal, which is showing for tourists in Dambana as a traditional and ancient, was a traditional for Sinhalese (Rutimeyer 1903; Sarasin 1893). The tradition of chewing of areca-nuts or bark of trees mixed with burned land-shells (“wantako”) was very common.

The soil is poor and unproductive. But the Wanniyala-aetto plant many different grains, vegetables and tubers. Most of the Wanniyala-aetto clear a piece of land close to the house to do swidden cultivation of maize and “kurakkan” millet (Eleusine coracana). This type of cultivation is practiced by both Sinhalese and Tamil small scale farmers and is called “chena”. An enormous fence surrounding the chena must resist the elephants, be taller than the sambhur’s leap and tight enough to keep out the hares. Staples include maize, finger millet (Eleusine coracana) and dryland rice. They obtain wetland rice from Sinhalese shops. Maize is sown just before the monsoon in mid-September, followed by kurakkan in October, and it is time for the boys to make use of the double-stringed bow – they guard the chena from birds, then sambhur who is looking for a taller plants, and wild boars seeking roots. The chena can’t be cultivated for more than two to three years – then it must lie fallow for ten to twelve consecutive years (Spittel 1950).

The harvest time of the kurakkan millet is in February, which is done by the wife and the children. The main danger in this period is elephant who can eat 250—300 kg of vegetation per day. In March or April the corn cobs are ready and all the family members cooperate before the monkeys steal the crop. The chena must be guarded night and day. The Wanniyala-aetto build watch huts on poles in the middle of the field and on the trees at the edge of it. The husband and sons bear this responsibility. If animals come, the watcher shouts and makes noises, hitting buckets with sticks and stones. If elephants threaten, the guards shout for assistance, make torches from bundles of tall grass and chase the elephants away from their homes (Stegeborn 1993).

Some Wanniyala-aetto also cultivate a small garden close to home, where they grow manioc, beans, chiles, curry leaves (Murraya koenigii), pumpkins and plantains. They may also try to grow some betel vines (Piper betel), which is highly valued among them, but it is cheap to buy, so they generally obtain it at the local tea-shop (ibid.). A very old habit adopted from the Sinhalese long ago is betel chewing, together with the accompanying ingredients – areca-nut and lime. Betel is chewed together with the bitter tasting areca-nut from the betel palm (Areca catechu). Before putting the wad in the mouth, a “pinch” of lime is smeared on the leaf to give it the “right” taste. To give a mildly spicy flavor they sometimes add pieces of cinnamon bark and cardamom seeds (ibid.). The areca doesn’t grow wild in the Eastern Province (Seligmann 1911) or in the bordering Uva Province where the Wanniyala-aetto live. They buy areca-nuts, betel leaves, chewing tobacco, lime, coconuts, spices and edible fruits such as jack-fruit (Artocarpus integrifolia) at Sinhalese owned tea-shops. But it was difficult to obtain them in the forests, so they have modified their own substitutes which can be found in the forests. Such analogs can be made from the bark of the “demate” (Gmelina asiatica) and “davata” (Carallia brachiata, corkwood tree) trees which substitute for the betel leaf and areca nut respectively (Seligmann 1911). Then they collect large, white land snails (Cyclophorus volvulus), burn them in fires, pulverize the shells into powder, add water to make a paste and use this in place of lime (Spittel 1950).

Important items used for trade are honey, meat, medicinal herbs, wild berries and cultivated grains. With the money they can buy clay vessels, cloth, salt, gunpowder and betel (Stegeborn 1993). Livestock herding has been adopted by a Wanniyala-aetto from their neighboring Sinhalese agriculturalists. On the first stage, Wanniyala-aetto came to watch the herds (the cattle graze around the house and sometimes the man’s wife or children bring them to other places where there is a fresh feed). In addition to the daily pay, they may receive a calf born that year. If they watch several herds, they obtain more livestock. The Wanniyala-aetto milk the cows, boil the milk and drink it or make yoghurt. Also they use cows to plow their rice-paddies. Some families have had four to five chickens freely walking inside and outside their houses, they were kept only for the eggs.

The Wanniyala-aetto do not eat their domestic animals such as their hunting dogs, chicken or cows. They are considered as pets and part of the compound like the children. The Wanniyala-aetto do not practice endocannibalism and do not eat their dead pets (Stegeborn 1993).

Nowadays the hunting and gathering traditions of the Wanniyala-aetto are almost lost. Some individuals sometimes go to collect honey and medicinal herbs. The native diet has changed considerably. Canned fish and meat replace fresh produce; sugar replaces honey; fewer vegetables are eaten. That contributes to new diseases: obesity, high blood pressure, heart problems, and alcoholism.

Nandadeva Wijesekera (1964) informed that “personal cleanliness of the Veddas leaves much to be desired, for sanitation and personal hygiene receive no attention. They wash their faces and mouths in the morning from a stream or water-hole nearby, as a matter of casual routine but thereafter for the rest of the day, although water may be available, they show no inclination to bathe in streams due to fear of being drowned”.

Also, Wijesekera supposes that the main reason is that they do not see the need to bathe nor can they think of any special benefit there from. He declares that very few “of the Veddas can swim even in streams and they do not dare to cross them unless forced to do so”, but he points out that the Veddahs love the rain, feel quite happy to get wet and thereafter sit by the fire (Wijesekera 1964). He mentions that the Veddahs seldom cut their hair, so their hair grow together into a massive lump. According to him, the act of beautifying the body, male or female, has never appealed to the Veddahs. Clothing was used only to cover their nudity. The hair is allowed to grow anyhow, the beard and moustache are not trimmed. But at the time of writing of that book (ibid.) the new habit of wearing by women necklaces of colored glass, beads, shell or bangles of ivory or brass; the practice of wearing ornaments (typical to Sinhalese and Tamils) became universal both among women and men. Due to Wijesekera, in the past flowers did not enter the scheme of adornment either of the person or hair, but “during recent times flowers and twigs have been used” (ibid.). We don’t have any concrete information about the group of the Veddahs which Wijesekera described, but the details given helped us to determine them as “Wanniyala-aetto”.

No mats were used by the Veddahs – they didn’t weave. Instead the skins of deer or sambur were used for sitting or sleeping and every family owned a number of them. At night a fire kept burning in front of the hut. The skins were also used to make bags or cushions. Also the “riti” bark was used for clothing and making bags. The custom of painting or tattooing their bodies or limbs was unknown to them (Brow 1978).

The average Wanniyala-aetto family size is six persons. Generally, residence is patrilocal. Descent is traced bilaterally. Marriage is preferred between patrilateral cousins, although anyone but the father’s brother’s child can be a potential spouse. A Wanniyala-aetto hamlet may involve three to nine families clustered together, each family in its own house. An average family includes a husband, wife and approximately three children.

Each group is named for local topography. Those dwelling near “mora” berries (Nephelium longana) are the “Morana Warige”. The people of the grasslands (“talawa”) are the “Tala Warige”.

Men were trained to use the bow, track animals, listen and interpret sounds of the nature, engage physical and mental activity and skills related to hunting. Adult women were the primary caretakers of the children. A child might be nursed until the age of four to five years – this prolonged lactation served as a method of birth control (Stegeborn 1993).

There was always someone at the house who took care of the youngest children, either an older sibling or someone from the extended family.

Stegeborn (1993) described in details the relationships with a dog. The hunting dog was a life-long partner, it was playmate for the children when it was a puppy and the disciplined companion of the hunter when it had become an adult. A well-trained dog knew when to bark and when to be quiet. The dog had to warn the house if elephants approach, but it had not been allowed to bark. It ran inside the house, sniffed its owner and danced around until everybody was alert. Stegeborn (ibid.) supposed that barking would have attracted the elephants to the hamlet because they seem to connect the dog with cultivation, and recognize that the barking sound means food, and perhaps salt from burned hearth wood. The domestic dog spent its life like any other member of the Wanniyala-aetto family, “the only difference is that he sleeps outside at night” (ibid.).

Veddas of Henebedda village (Nilgala district) belonged to “Namadewa” warige at the time of Seligmanns’ research (1911) lived in bark-covered huts, gather honey and hunt, several of them possess guns, and some of them rear cattle for the Sinhalese villagers. But Bailey (1863) first induced some Veddahs in the Nilgala district to make chenas (cultivated rain-fed lands) about the middle of the 19th century, before which all the Veddahs in this district were probably living their natural hunting and gathering life. While Veddahs of Danigala village of the same district were named as the classical “wild Veddahs”, at the time of Seligmanns’ research (1911) their own customs have been almost entirely forgotten. They have had chena and banana plantation and did a good trade in cattle both by herding for the Sinhalese (in case of herding received every fifth calf that born).

A number of “Morane” men stated that their ancestors came from Moranegala in the Eastern Province, but no Unapane man ever suggested that his clan had originally come from the place of that name near Kallodi. “Moranegala” is a hill name, and probably the hill has been named from the “mora” trees (Nephelium longana) which it may be assumed grew there, so that “Moranegala” means “the hill of the mora trees”, and it might be argued that Morane warige derived it’s name from the “mora” tree. In songs, collected at Sitala Wanniya, both men and women of “Morane” warige are addressed as “mora flowers” (Deschamps 1892).