Полная версия

Managing Internationalisation

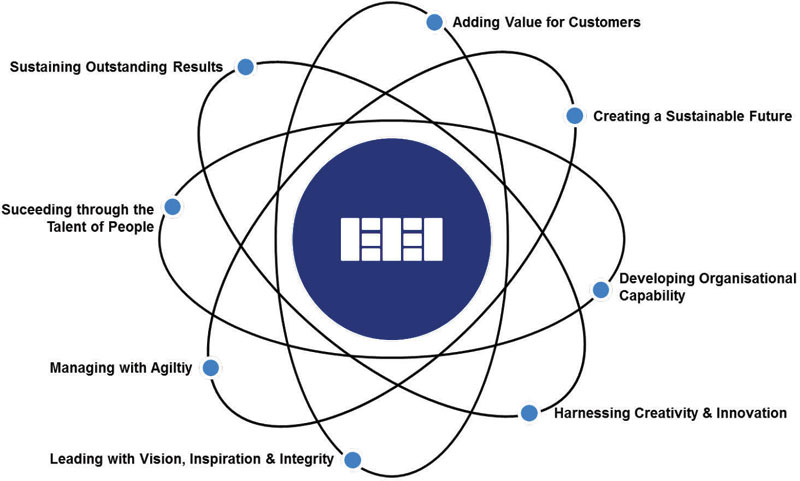

Every management model is based on key concepts that explain the underlying management philosophy. These concepts provide important guidance on the interpretation of model criteria in case they are not self-explanatory. Before using any kind of model it is always advisable to compare its basic philosophy with one’s own because incompatibilities in this respect can reduce the usefulness of a tool considerably.

Figure 1-7: EFQM Fundamental Concepts of Excellence26

The EFQM Excellence Model supports any kind of organisation in its endeavour to attain excellence with the goal of meeting or exceeding the expectations of its stakeholders by achieving and sustaining superior levels of performance. The essential foundation of this quest is built by 8 underlying principles called the Fundamental Concepts as depicted in Figure 1-7.

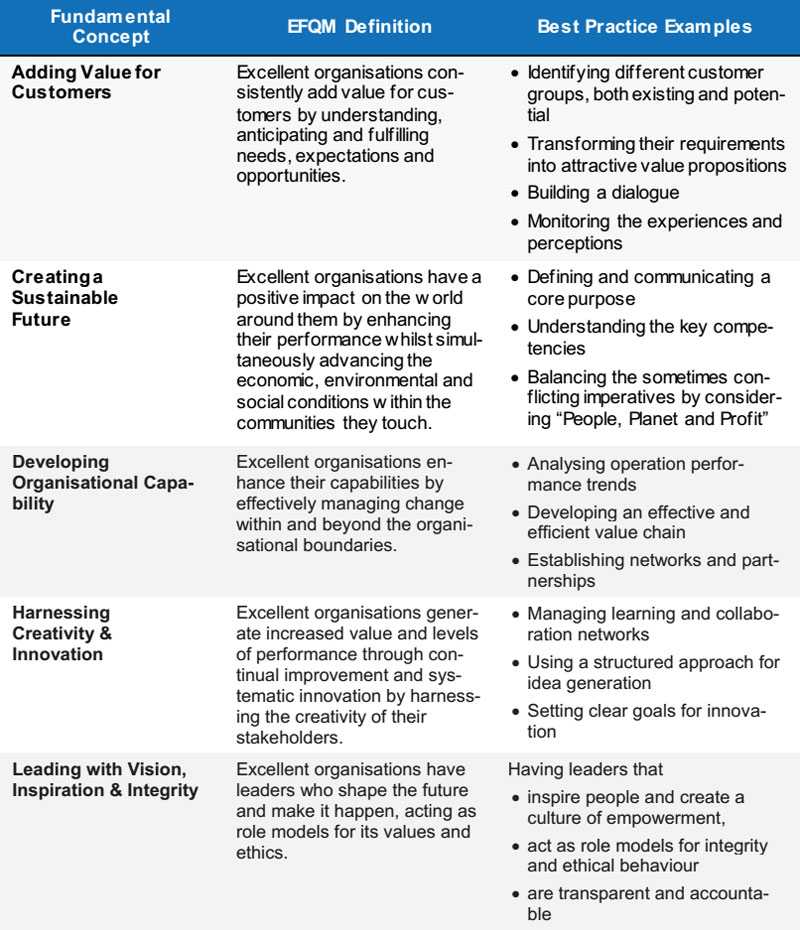

Figure 1-8: EFQM Fundamental Concepts: Definitions and Best Practices27

Each Fundamental Concept of Excellence is defined against the backdrop of a management approach of an excellent organisation. These definitions are augmented by aspects of what excellent organisations do to transfer these principles into practical activities. The main definitions and some of their constitutive best practices are specified in Figure 1-8. The management approach described in the Fundamental Concepts is cast in a structure of a holistic management model with 9 criteria: the EFQM Excellence Model.

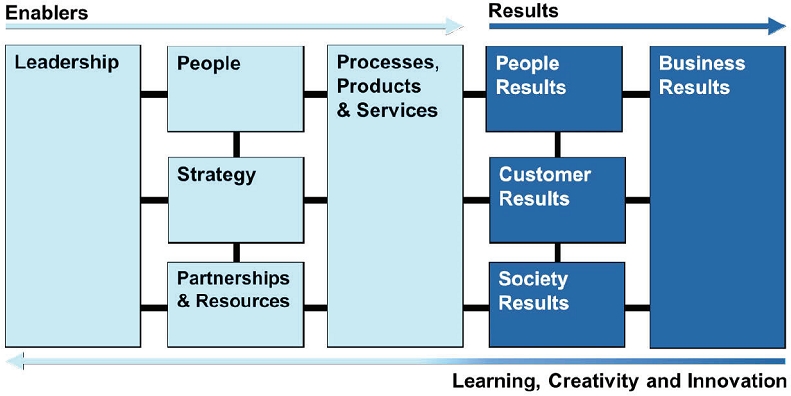

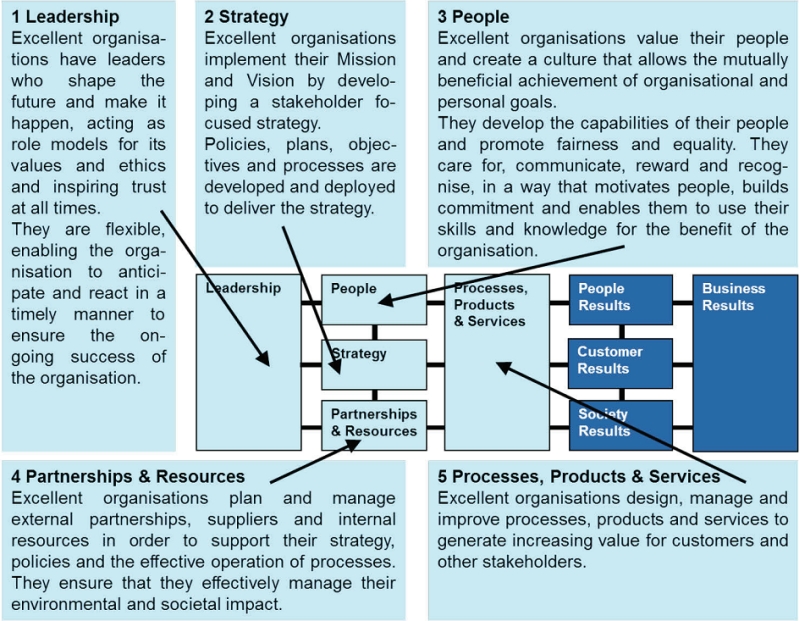

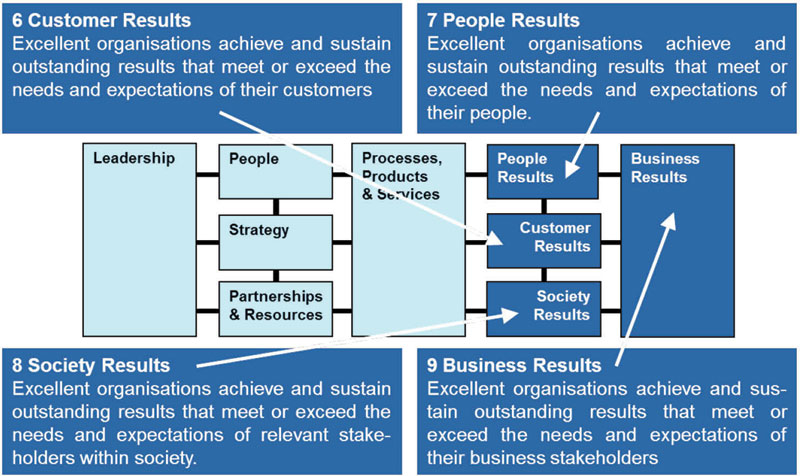

1.3.3The EFQM Excellence Model Framework 2013The EFQM Excellence Model 2010 offers through its non-descriptive framework a guiding structure for any kind of organisation striving for excellence. It is presented in Figure 1-9. The nine criteria and their subdivisions allow depicting precisely an organisation’s way of offering value (“enablers”) and the resulting goal attainment (“results”).

Figure 1-9: The EFQM Excellence ModelFramework201328

Figure 1-10: Definitions ofthe EFQM Enabler Criteria29

The five enabler criteria on the left side of the model cover what an organisation does to fulfil the various expectations of its stakeholders and how it does it. They consist of the criteria 1 Leadership, 2 Strategy, 3 People, 4 Partnerships & Resources and 5 Processes, Products and Services. The results stem from the enablers and depict what the organisation achieves. The balanced view on results is expressed by the four criteria 6 Customer Results, 7 People Results, 8 Society Results and 9 Business Results. As any excellent organisation is a learning organisation, the dynamic of continuous improvement through feedback is represented by the arrow at the base of the model stating “Learning, Creativity and Innovation”. Each criterion is clearly defined in order to explain its general meaning. An overview of the criteria definitions is provided in Figure 1-10 (for enablers) and Figure 1-11 (for results).

Figure 1-11: Definitions of the EFQM Results Criteria30

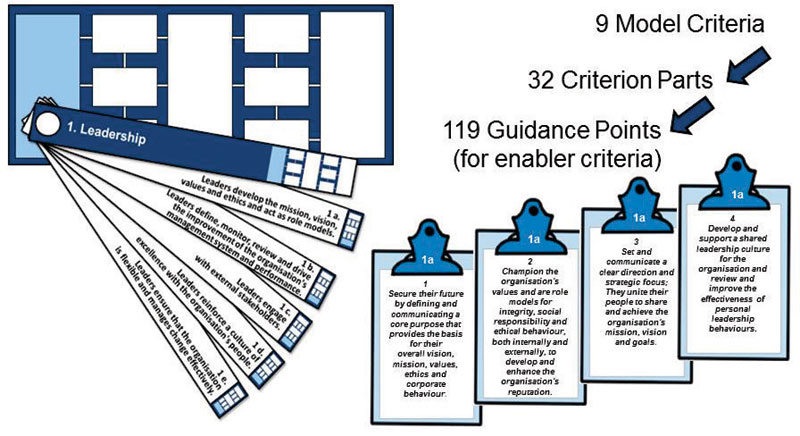

The high level definitions of the criteria only allow a very rough structure of a management system. For assessing the maturity of an organisation as well as its strengths and weaknesses, a more detailed approach is necessary. Therefore, the nine criteria are subdivided in criterion parts and these are further elaborated in guidance points. The 32 criterion parts describe different facets of what an excellent organisation typically does in the area of the defined criterion and what therefore should be considered during an assessment. On the third and lowest level of the model, the guidance points provide tangible best practice examples of how to implement the ideas. These guidance points link the EFQM Excellence Model to the Fundamental Concepts. Some of them provide an adaption of one part of a Fundamental Concept to fit the specific context of the criterion part. Other guidance points repeat the text from the Fundamental Concept precisely. Through the guidance points, the structure of the model allows to grasp connections between the different criteria and by that to identify management approaches that are able to integrate several goals at once. This adds another dimension to the otherwise two-dimensional model. These links are depicted by the connecting lines in the EFQM Excellence Model Framework. A graphic example of the EFQM levels is provided in Figure 1-12.

Figure 1-12: Exemplary Levels of the EFQM Excellence Model31

It is important to keep in mind that the 119 guidance points used for exemplifying the five enabler criteria are not meant as a check list, so it is not necessary for an organisation to follow them all. Nor is the list of guidance points meant to be exhaustive, as there are other ideas and approaches that fit into a criterion part without being mentioned in a guidance point. The EFQM Excellence Model as an open and non-descriptive model allows and expects individual solutions that match business sector, size, culture and strategy of a specific organisation. However, the guidance points facilitate the search for a fitting improvement measure, in this respect being proper guides for a leader facing management challenges.

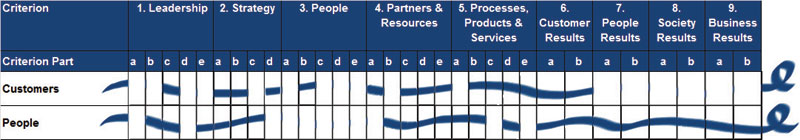

Figure 1-13: Exemplary Red Threads Through the EFQM Excellence Model32

It is possible to follow certain ideas or aspects of management through the model as they are referred to in several guiding points. The EFQM depicts in their 2013 model brochure the integration of their fundamental concepts into the model by highlighting those criterion parts of the enablers where the text of a certain fundamental concept is reflected directly in one of the attached guiding points.33 This exercise can also be done in a broader sense for any aspect a manager would like to focus on, for example customers or ideas and impacts of the introduction of a risk management system. As shown in Figure 1-13, each of these aspects can be followed through the model. Ideas how to optimise the benefit from the customer’s perspective can be found for example in 1c (leaders are transparent and accountable to their customers and encourage them to participate in activities that contribute to the wider society), in 2a (gather customer’s needs and expectations as strategy input), 2b (analyse current performance trends, for example how customer expectations and promises to the customers are kept), 2d (communicate their strategy to their customers), 3b (attract the right people and ensure that all employees have the necessary competencies to fulfil the needs of the customers), 4a (identify and work together with partners to ensure enhanced value for the customers), 4c (optimise the impact of their product lifecycle and services on public health and safety including that of the customers), 4d (involve customers in the development and deployment of new technologies to maximise the benefits generated), 4e (establish approaches to engage relevant customers and use their knowledge in generating innovation), 5a (design and manage processes to optimise customer value – also beyond the boundaries of the organisation), 5b (develop products and services that create optimum value for customers), 5c (define different customer groups and anticipate their needs and expectations), 5d (produce and deliver products to need or exceed customer needs and expectations), and 5e (manage and enhance customer relationships). The outcomes of these approaches are measured in 6a and 6b (customer perceptions and performance indicators with impact on the perceptions of customers). Explanations concerning the depicted relevant criterion parts for people are provided online at the accompanying website combined with the solution to the following exercise.

The internationalisation process that forms the structure of this textbook is based on the EFQM criteria. Therefore, more details of each criterion and the associated criterion parts will be explained at the beginning of the corresponding chapters. As this book will only present selected parts of the EFQM Excellence Model, it is highly recommended to acquire the original brochure of the model which can be obtained at www.efqm.org.

1.3.4The EFQM RADAR LogicFor assessing the excellence level of an organisation the EFQM offers a logical method based on the Deming or PDCA Cycle. According to the Deming Cycle a continuous improvement of processes or systems is based on several successive phases starting with establishing plans, processes and (measurable) objectives to the delivery of a certain output (PLAN), implementing and executing these plans (DO), reviewing the actual results (CHECK) and taking corrective actions in case significant differences between the actual results and the planned objectives occur (ACT).34 The PDCA-Cycle lies at the heart of all improvement-related management models and is used for example in the ISO 9001 quality management systems’ requirements.

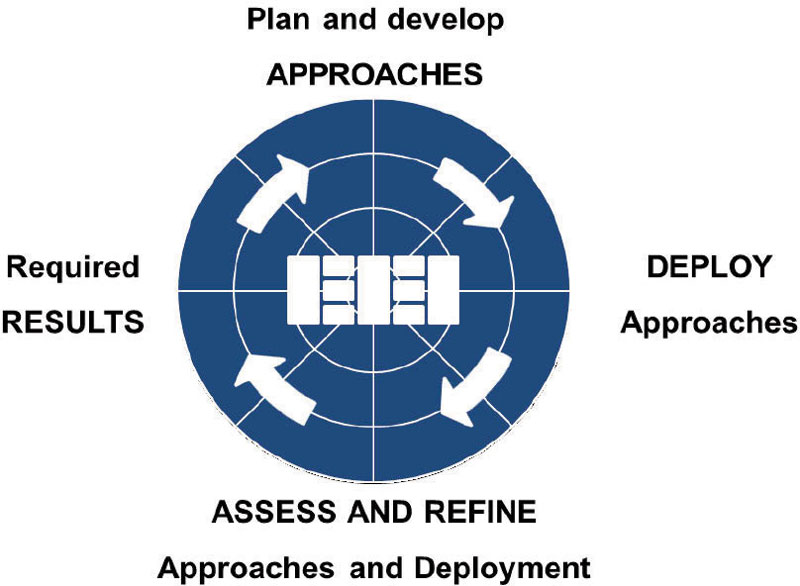

The EFQM calls its derived approach RADAR® logic. It consists of four consecutive phases that an organisation needs to execute in order to ensure continuous improvement and sustainable outcomes and is represented in Figure 1-14. In the first phase, the organisation determines the RESULTS it wants to achieve according to its strategy. In the second phase the organisation plans and develops an integrated set of comprehensive APPROACHES to deliver the results from an actual and future-oriented perspective. In the third phase the approaches are DEPLOYED systematically to ensure a successful implementation. In the fourth phase the organisation has to ASSESS and REFINE its approaches according to the analysis of the achieved results and based on its on-going learning activities. Therefore, the cycle starts again with defining the desired results. The degree to which an organisation is able to consequently follow this rigorous improvement cycle is the basis for assessing its level of excellence. For an EFQM assessment, a detailed set of requirements and possible levels of fulfilment based on the RADAR® cycle was invented that is depicted in the so called RADAR tools. One RADAR tool (also called RADAR matrix) deals with the results, as it depicts the first phase of the cycle and is thus used for the result criteria. The second RADAR matrix is used for the assessment of the enabler criteria and depicts the phases two to four of the RADAR logic.

Figure 1-14: The EFQM RADAR® Logic35

VIPs

1.4Process Model “Managing Internationalisation”

Figure 1-15: The Internationalisation Process

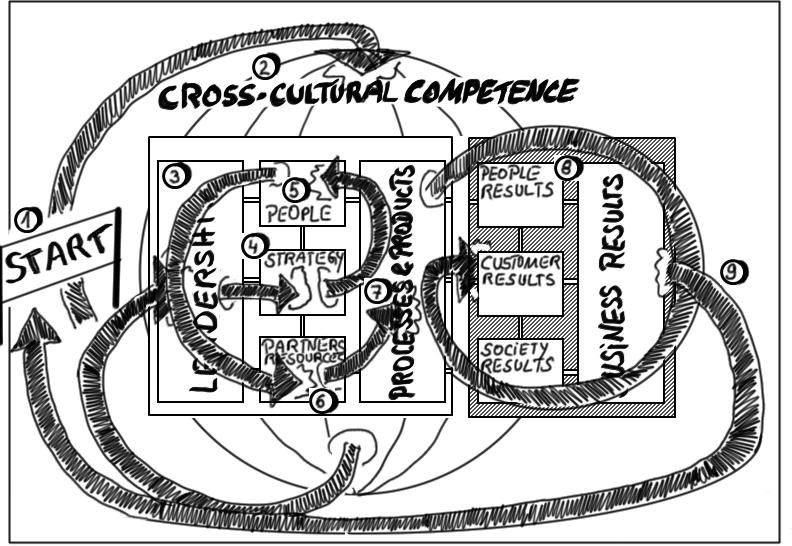

The management logic of the EFQM Excellence Model can be used to define the path through the internationalisation process, as shown in Figure 1-15. The management process itself starts with leadership awareness and competence to steer the organisation through the internationalisation process. This is followed by the definition of an international strategy which sets the path for the following implementation. The strategy is implemented through the following steps: managing people in an international environment, managing international partners and resources as well as managing products and processes globally. Based on a sustainability approach the results achieved will be compared with the (strategic) goals set, defined by ways of an individual balanced scorecard. A strategy review based on the outcomes will follow to ensure that the longterm vision of the company is still valid and the path to be followed seen as appropriate. These internationalisation steps are supported by the development of crosscultural competence, which is required for every action and decision in internationally operating organisations. Therefore it defines the starting point for the following elaborations of this book.

1.5Citations & Notes

1 Morschett, D., Schramm-Klein, H., & Zentes J. (2010), pp. 71-82; Holtbrügge, D., & Welge, M. K. (2010), pp. 25-26.

2 Contents based on Morschett, D., Schramm-Klein, H., & Zentes J. (2010), p. 72, figure 4.1; Holtbrügge, D., & Welge, M. K. (2010), p. 24, tab. 1-7

3 Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (1977)

4 A good overview of theories dealing with foreign direct investments is provided in Holtbrügge, D., & Welge, M. K. (2010), pp. 54-78

5 UNCTAD (2013b)

6 UNCTAD (2010), p. iii

7 UNCTAD (2010), p. XVIII. Unfortunately, the newer World Investment Reports concentrate on FDI inflows and outflows but do not offer a recent count of TNCs.

8 UNCTAD (2014), p. 16

9 Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1986); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1987a); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1987b); Ghoshal, S., & Nohria, N. (1993); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1998)

10 Based on Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1986), p. 377; Kutschker, M., & Schmid, S. (2011), p. 300

11 Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1986); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1987a); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1987b); Ghoshal, S., & Nohria, N. (1993); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Industry examples from Morschett, D., Schramm-Klein, H., & Zentes J. (2010), pp. 43-44 and Kutschker, M., & Schmid, S. (2011), pp.301-304.

12 Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1998), p. 18

13 Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1986); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1987a); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1987b); Ghoshal, S., & Nohria, N. (1993); Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. (1998); Morschett, D., Schramm-Klein, H., & Zentes J. (2010), pp. 34-35; Kutschker, M., & Schmid, S. (2011), pp.301-304.

14 Economist Intelligence Unit (2012)

15 Rüegg-Stürm, J. (2004a), p. 12

16 Rüegg-Stürm, J. (2004b). More information about the use of this integrative approach can be obtained at the website of Universität St. Gallen: http://www.es.unisg.ch/en/custom-programs/approach/intergrative-approach.php (access 01.03.2015); A good overview offers the author’s German publication (Rüegg-Stürm, J. (2004a)). An extract of it is obtainable online: http://www.michaelegli.ch/html/img/pool/Neues_St._Galler_Managementmodell.pdf (retrieved 01.03.2015).

17 US Department of Commerce & NIST (2015). The model will be updated yearly and the recent brochures are for sale and partly displayed at the NIST website. Information about the use of this model for awards in different countries can be obtained from US Department of Commerce & NIST (2005). As “Home of the Baldrige Performance Excellence Program” the NIST offers also many publications of MBNQA winners with best practices free of charge, true to their mission to foster improvements.

18 US Department of Commerce & NIST (2015); graphics also available from http://www.nist.gov/baldrige/graphics.cfm

19 US Department of Commerce & NIST (2015); graphics also available from http://www.nist.gov/baldrige/graphics.cfm

20 NIST (2010)

21 EFQM & ILEP (2012). A short introduction to the EFQM itself, the EFQM model, its Fundamental Concepts and possible uses can be retrieved from the official EFQM website (www.efqm.org). A short overview of the model is offered as pdf publication free of charge: EFQM. (2012). An overview of the EFQM Excellence Model. Retrieved from www.efqm.org/sites/default/files/overview_efqm_2013_v1.1.pdf. The EFQM offers at its website model related publications in several languages, mainly for sale. For German users that work internationally, the dual language version (German/English) used here can be highly recommended. For some award processes, free information on best practices concerning selfassessments and the award process is provided on the internet. For example for the German Excellence Price called Ludwig-Erhard-Preis (www.ilep.de)

22 EFQM (2015d)

23 EFQM (2015e)

24 EFQM (2015f)

25 NIST (2010)

26 EFQM & ILEP (2012), p. 6

27 Definitions taken from EFQM & ILEP (2012), pp. 8-14

28 EFQM & ILEP (2012), p. 16

29 Definitions assembled from EFQM & ILEP (2012), pp. 18-31

30 Definitions assembled from EFQM & ILEP (2012), pp. 34-40

31 Definitions from EFQM & ILEP (2012), p.18

32 General idea and parts of the attribution based on EFQM & ILEP (2012), p. 42

33 EFQM & ILEP (2012), p. 42

34 Deming, W. E. (2000), p. 88. (Deming calls it in his own book the “Shewhart Cycle” but notes that it has been called Deming Cycle since he introduced it in Japan in 1950). The PDCA cycle is referred to regularly in books about (Total) Quality Management, for example Juran, J. M., & De Feo, J. A. (2010), pp. 204-205 or Oakland, J. S. (2014), pp. 120-125 (with various decuctions and uses for example pp. 250-252, 263-266, 296).

35 EFQM & ILEP (2012), p. 44

Readers are aware of the importance of recognising and respecting cultural differences for facilitating international relations of any kind. They are able to explain and compare different frameworks for distinguishing organisational or national cultures. The awareness about their own cultural perspectives and resulting judgements is heightened and the ability to reconcile cultural dilemmas enhanced.

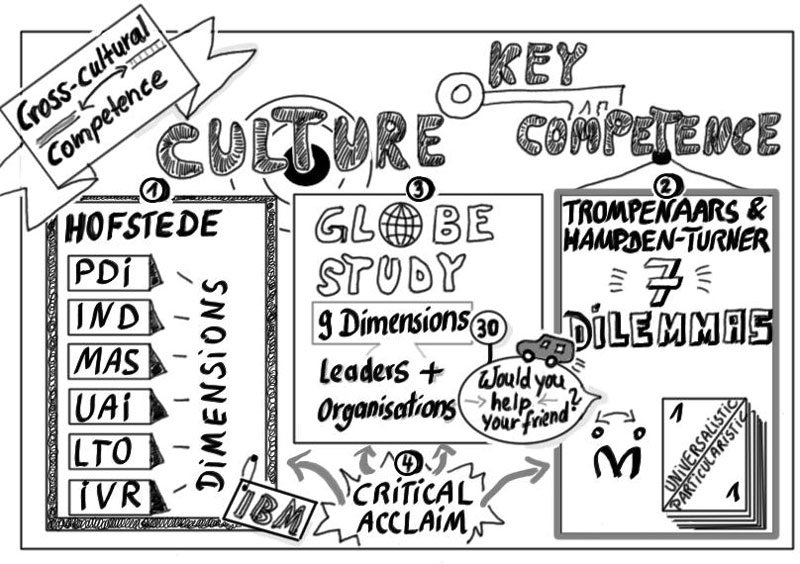

Knowledge about intercultural differences and their manifold effects on the building blocks of the management system is a key prerequisite for a successful internationalisation. This section explains typical pitfalls of mono-cultural thinking in a global business environment and provides different business-related frameworks for distinguishing cultures. The use of these frameworks in designing and implementing international management systems can foster an organisational climate embracing the opportunities of multicultural approaches for doing business. Figure 2-1 delivers the concept map for treatment of the key issue Cross-Cultural Competence.

Figure 2-1: Concept Map “Cross-Cultural Competence”

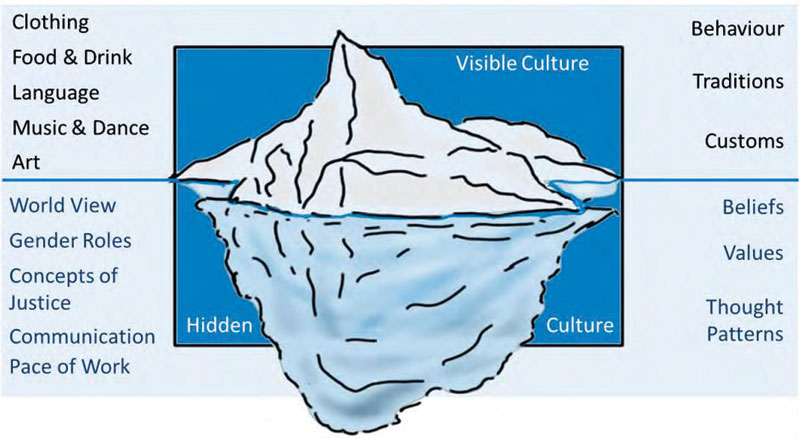

2.1The Importance of Intercultural Understanding for International Business IssuesCulture is still one of the most iridescent concepts in science. When people first think about culture, it is usually about the obvious aspects like behaviour, traditions and customs. French people carrying baguettes, African people in colourful caftans and the formal bows in Japanese greetings – all these observations shape our perception of culture. But these observations form only the tip of the (cultural) iceberg. The famous cultural iceberg metaphor (usually attributed to Edward T. Hall from his book published 1976, although he does not use the term)1 illustrates that the essential cultural differences lie underneath the visible spectrum, as depicted in Figure 2-2. Dissimilarities in beliefs, values and thought patterns are far more relevant for intercultural misunderstandings than different traditions that are more prominently displayed and therefore create awareness more easily.

Figure 2-2: The Cultural Iceberg

Understanding cultural-induced behaviour is a prerequisite for successful business operations in any international context. A lack of cross-cultural competence gives rise to manifold faults in information retrieval, decision making, negotiating and leading that might become disastrous for the organisation’s long-term achievements. Throughout the EFQM Excellence Model, the correct assessment of cultural beliefs and values is presumed for finding effective responses. For example, leaders can only act as role models if their ideas of how to act with integrity and how to follow high standards of ethical behaviour are in line with the respective expectations of all of their team members. As these expectations vary from culture to culture, acceptance can only be ensured by a thorough research of possible misunderstandings. In dealing with customers and stakeholders, cultural misunderstandings can be of even more dramatic consequences. A misinterpretation of customer requirements might lead to the development of non-marketable products. A violation of unspoken negotiation rules might ruin a bid for a long-term contract.

The development of intercultural sensitivity is the most effective countermeasure for this kind of intercultural conflicts. Intercultural sensitive people are able to apply skills of empathy and adaptation of behaviour to any cultural context with varying degrees of sophistication. Unfortunately, this ability does not come naturally. It is something that has to be learned and grows whenever a person is exposed to foreign cultures with an open mind. Milton Bennett describes typical stages in this very individual development process from first denial to final integration in his Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity as illustrated in Figure 2-3.2 People growing up in a monocultural environment accept the culture they grew up with as the only one existing. Exposure to other cultures leads first to denial of differences. When denial is no longer possible, people start experiencing their own culture as more advanced and “better” than the other, known as the defense phase. This phase is usually accompanied by the use of stereotypes in order to confirm prejudices. Both early phases of cultural development could take exaggerated forms of aggressively eliminating foreign cultures and their representatives or – on the contrary – romanticising them. After realising existing similarities between their own and the foreign culture (usually in superficial aspects like customs or food), people tend to minimise the fundamental differences, believing that there are generally recognised patterns of human behaviour that enable effortless and successful communication. With the next step, the ethnocentric stages are overcome and people enter the ethnorelative stages of intercultural development. These start with a genuine acceptance of differences in cultures and of the right to use different solutions to typical human problems. This does not include an agreement with the solutions a certain culture exhibits, which are continually scrutinised in order to accumulate more knowledge. Expanding the view of the word leads to the ability to understand other cultures and to behave appropriately in their cultural frameworks. In this adaption phase, people are able to shift their frame of reference and use empathy for the benefit of good communication. The final stage “integration” allows a person to move in and out of different worldviews at will. For these people, a specific culture is no longer a constitutive part of their definition of self.