Полная версия

Managing Internationalisation

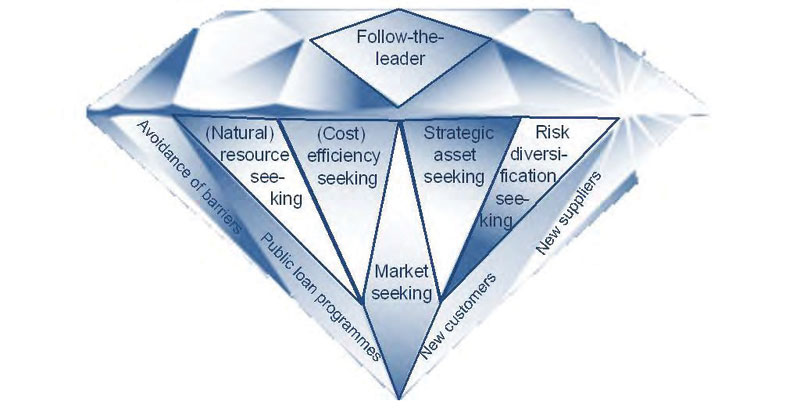

Reasons and motives for internationalising an organisation are multi-faceted, as illustrated in Figure 1-3. For most organisations the primary motive is still the search for markets to ensure sustainable growth. Underlying reasons might be the (assumed) existence of attractive customer segments, demand for the offered products and services, a generally huge market size or an attractive market growth. Sometimes, the decision in favour of entering a new market is paired with a requirement to avoid the related tariffs or other trade barriers and to partake in public loan programmes offered by the respective government. In this case, opening new or relocating existing production sites is a logical consequence of the original market-seeking intent. Another important motive that appears individually or agglomerated is the necessity to ensure the availability of raw materials or other crucial and scarce resources. Cost-efficiency seekers try to establish production facilities in locations that provide essential resources at low cost (for example cheap labour costs), ensure a shorter time-to-market through cutting the distance to the customers or realise faster production cycles due to the immediate availability of efficient and good suppliers. Strategic asset seekers internationalise their business because they have a high need of well-trained people with special skills (for example in finding innovations) or are looking for international partners to complement their own product portfolio or research activities. Pushing internationalisation processes out of a risk diversification perspective is a motive on the rise due to an increased emphasis on risk management. Finally, many organisations feel obliged to mimic the international actions of their main competitors, which is labelled follow-the-leader motive.1

Figure 1-3: Multi-Faceted Motives for Internationalisation Processes2

When the need for internationalisation is recognised, organisations have different possibilities to start the internationalisation process. The classical Uppsala Model from Johanson and Vahlne (1977) assumed that companies build up their presence in foreign markets incrementally along typical steps. This establishment chain was discovered based on case studies of Swedish companies and considered on the one hand the continuing acquisition and use of knowledge about the foreign market and on the other hand the commitments to the foreign market. The chain starts with irregular export activities and gradually evolves to the use of independent representatives, the founding of own sales subsidiaries and finally the establishment of a manufacturing plant in the foreign country. The authors observed also that the process was usually started in markets that had many common characteristics with the home market and that the international establishment took longer in case the knowledge of the target market was very low, or in other words the market was deemed exceptionally foreign in nature. From these observations they derived the concept of “psychic distance”, defined as the sum of factors inhibiting the flow of information to and from the foreign market. These factors are supposed to be mainly based on differences in culture, language, business practices and industrial development. An organisation naturally tends to start international activities in a market with low psychic distance, for example in a neighbouring country using the same language where the organisation feels to have a good knowledge of. Gradually, market knowledge of other countries further along the psychic distance chain will be collected. If the endeavour of internationalisation was implemented successfully in the first market, the internationalisation will be extended to the next country along the psychic distance chain.3 According to this theory, a German company would be expected to start with exporting its products to Austria followed by the later establishment of a sales subsidiary there. The next internationalisation step could then be exporting its products to Denmark or the Netherlands.

The establishment chain is nowadays not deemed an appropriate view of internationalisation processes. Organisations use business contacts and partner networks to collect information and share investment risks. This enables them to develop their international presence at a jump, starting for instance directly with a manufacturing plant in China instead of gradually testing export opportunities. Also, the emergence of “born globals” demands attention, referring to organisations that directly resume their business activities on a global scale as this is a dominant part of their business model (e.g. google). The current scientific landscape is defined by many different theories of internationalisation processes, which all focus on special aspects, for example motives, risk or competition drivers or certain industries.4 Mainly the promotion of the importance of partnerships and networks could be singled out as a common denominator. Although these theories provide interesting insights into trends and patterns, they are not suitable for supporting managerial decisions. Therefore it will be desisted from further discussion.

Not every organisation that establishes routine cross-border activities is already a truly international organisation or even a “global player”. Such a classification would require the extension of the organisation’s management system and processes in a manner that laws and customs of other countries gain a considerable influence on the way the organisation acts. Terms coined for these kinds of organisations include Transnational Enterprise (TNE), Multinational Enterprise (MNE), Multinational Corporation (MNC) or Transnational Corporation (TNC), that are all basically used as synonyms. There are many different definitions mainly based on the aforementioned distinction available. The most widely accepted stems from the UNCTAD and is used for its Transnational Corporation Statistics: “A transnational corporation (TNC) is generally regarded as an enterprise comprising entities in more than one country which operate under a system of decision-making that permits coherent policies and a common strategy. The entities are so linked, by ownership or otherwise, that one or more of them may be able to exercise a significant influence over the others and, in particular, to share knowledge, resources and responsibilities with the others.”5 It is to be noted that this definition does not comprise a specific majority control, although internationally a minimum equity capital stake of 10% or any equivalent including voting power is common. Therefore an exact classification might require selecting the main parent company for a considered associate enterprise, which is usually the one with the highest percentage of ownership. The relevance of TNCs is not derived from mere transnational ownership but instead from the fact that they are considered to be organisations “with formidable knowledge, cutting-edge technology, and global reach”6. In 2009, the UNCTAD reported the existence of 82.000 TNCs, with 80 million workers employed and their foreign affiliates accounting for a share of 11% in global gross domestic product.7 Additionally, these TNCs can be classified by their transnationality index, that provides information on the relevance of the activities outside an organisation’s home country and is calculated as the average of the three ratios foreign to total sales, foreign to total assets and foreign to total employment. The German Metro AG for example reached 2011 a comparatively high transnationality index of 0,62 and reported 33 countries of operation.8

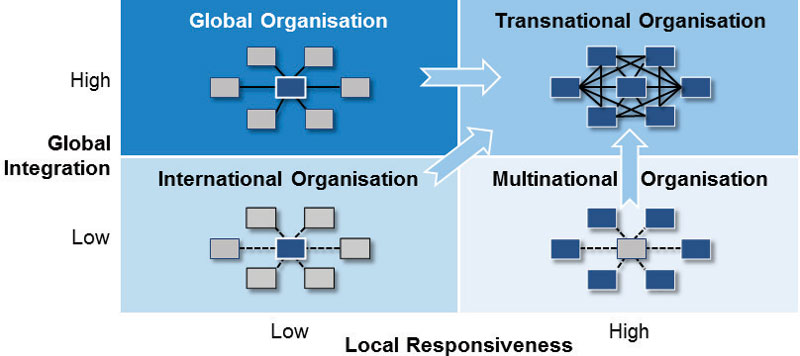

From a scientific perspective, Bartlett and Goshal’s Integration/Responsiveness Framework provides a clear strategic distinction between different kinds of organisations with relevant cross-border activities, as depicted in Figure 1-4. Their portfolio contrasts environmental pressures for global integration with the pressures of local responsiveness as two independent dimensions whose combination of low or high value, respectively, suggest a certain configuration of the organisation. Typical forces for global integration stimulate specific reactions. The importance of multinational customers or competitors (often stimulated by trade liberalisation) combined with high investment intensity for example activates further strategic coordination. Forces like homogeneous tastes and needs, high technological intensity as well as the need for realising cost reductions induce looking for economies of scale, economies of scope, economies of experience and/or worldwide innovation lead to operating integration. The second dimension, pressures for local responsiveness, includes differences in customer needs and tastes, (local) needs for substitutes, individual market distribution structures or host country government demands. In these cases, it is important to assimilate to the special requirements by establishing individual processes for the local environment or by offering local variations of the products or services in order to be attractive for customers and partners alike.9

Figure 1-4: The Global Integration/Local Responsiveness Framework10

This Integration/Responsiveness Framework advises upon the choice of a global strategy for organisations facing high global integration pressures (for example due to a strong global competition) but being able to offer a highly standardised product as the pressures for local responsiveness are low. Organisations choosing this approach typically build cost advantages through centrally managed global-scale operations. These global organisations constitute the classic case of a global player, as most of the strategic decisions, responsibilities, resources and assets are centralised in the (home country) headquarters, which exerts a tight control over all overseas operations that deliver the products to a global market. Typical representatives of this kind of organisations are found for example in the aircraft or consumer electronics industry. In contrast, organisations facing low global integration pressures but instead high environmental forcers for local responsiveness follow a multinational (also called multidomestic) strategy approach and are formed as a decentralised federation of independent organisations. Many of their key decisions, responsibilities and assets are decentralised in order to better meet the individual market needs. The relationship between headquarters and subsidiaries is comparatively informal and usually focused on financial control. Multidomestic or multinational organisations are mainly found in industries whose products depend on languages or culture-specific tastes like for example publishing houses, foods and beverages. In cases where both forces contemplated are low, the resulting international organisations are largely based on transferring the products or processes of the parent company to their subsidiaries for worldwide diffusion. Foreign activities are seen as remote outposts that are highly dependent on the headquarters’ resources and support the parent company with their profits. Therefore, the organisation’s management and strategy is oriented towards the home country, exercising a tight control over their foreign subsidiaries but without systematically integrating host country organisations and their perspectives. These organisations are found for example in the textile industry.11

So far, all introduced strategies are dominated by a single strategic demand. However, in the current global competition organisations increasingly face high forces of global integration and high pressures for local differentiation with a growing emphasis on worldwide innovation. According to Bartlett and Goshal, the appropriate transnational strategy to compete effectively in this extremely demanding environment requires the simultaneous development of “global competitiveness, multinational flexibility and worldwide learning capabilities”12. Transnational organisations are truly interdependent and make selective centralising or decentralising decisions. Essential resources are centralised within the home country headquarters to protect the core competencies and in part realise economies of scale. Other resources and learning opportunities are geographically dispersed in specialised locations which ensures the necessary flexibility. Products are adapted to local requirements where necessary despite being part of an integrated production process that provides standard components from a single location to all relevant subsidiaries worldwide. Improvements and innovations are promoted in all subsidiaries and headquarters alike and outcomes are shared between all operations and subsequently diffused around the globe. Transnational organisations are characterised by large flows of knowledge, capital, people and products between subsidiaries and between headquarters and subsidiaries. The resulting organisation can be described as an integrated network. The environment described is typical for the telecommunication, pharmaceutical and media industry. More and more industries are gradually developing towards the transnational sector, as is the case for example with the automobile and banking industry. It is obvious that a transnational strategy with its high demands on integration and coordination provides a huge challenge. Therefore, successful examples are rare.13

When an organisation pursues a transnational strategy, decisions become far more complex, as multiple market requirements and the needs and capabilities of many different subsidiaries have to be taken into account and balanced out. In addition to that, non-business matters or soft factors require more management attention, especially the need for productive and harmonious cross-border relationships despite cultural differences and language barriers. Whereas the challenges presented by strategic, organisational and operational matters are anticipated and considered, corresponding soft factors are regularly ignored. A global survey of 572 executives explored internationalisation challenges and especially the role of cross-border collaboration and communication. More than 50 % of the respondents rated cross-border collaboration as very important, not only with all kinds of external partners but also within their business unit and their whole organisation. 64% reported cross-border collaboration as having been a critical factor in performance improvement. Despite its relevance, 51% admitted that linguistic and cultural diversity make it very difficult. Communication misunderstandings were reported to have stood in the way of establishing major cross-border transactions several times (6%) or a few times (43%) with incurred financial setbacks. Interestingly, due to a generally enhanced command of English, the diversity of languages across countries is no longer seen as the crucial cause for misunderstandings (only 27% reported this as most likely reason), instead different norms of workplace behaviour (49%) and differences in cultural traditions (51%) constitute the main challenges. Factors such as local customs and languages were stated to hamper their company’s international expansion plans significantly, especially in Russia (89%), Spain (88%), Brazil (70%) and China (67%).14

In summary, dealing competently with intercultural issues constitutes one of the most important factors for a successful internationalisation. The basics of cross-cultural competence will therefore be addressed in detail in chapter 2 which is dedicated to this key issue.

VIPs

1.2The Use of Holistic Management Models

Managing any kind of organisation is a complex process and is made even more complex in an international and therefore usually unknown environment. The smaller and the more focused an organisation is, the easier it is for its (top) managers to rely on their experience and instincts for good management decisions. Consequently, the more an organisation is diversified, the more people are contributing to its success and the more it is dispersed over different locations, the more a clear structure is needed in order to not involuntarily overlook important matters.

Holistic management models were developed to ensure a balanced and complete view on all management matters of different types of organisations. They provide generalised issues that have to be solved in order to steer an organisation effectively to longterm success. These models are used for guidance in the management process, for assessing the maturity of an organisation’s management system and for electing the best organisations at quality or excellence price competitions.

Since the 1970s several holistic management models were published. To date, there are three models with international relevance: the (New) St. Galler Management Model, the model of the Baldrige Excellence Program and the EFQM Excellence Model.

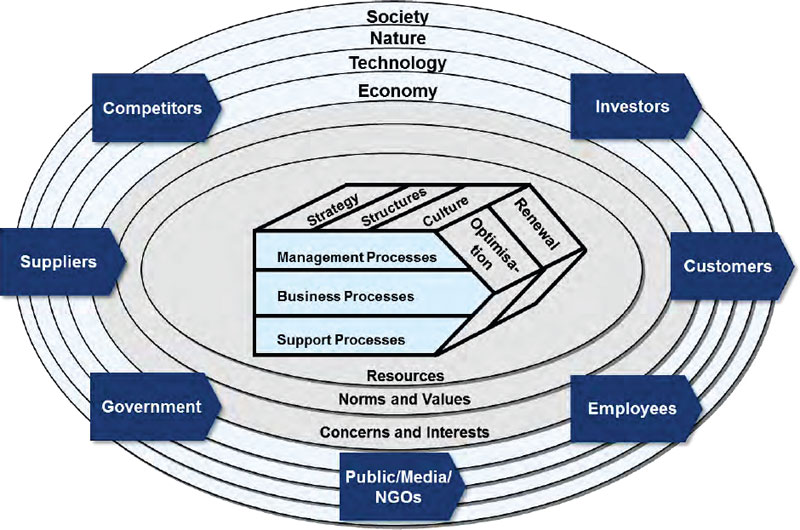

The New Management Model is an integrative framework that provides a system-oriented view of a company and is edited by the Management Institute St. Gallen. It therefore presents predominantly a scientific view. The distinctive graphic as presented in Figure 1-5 shows the company as a productive system in the centre of its surrounding network. It consists of six essential concepts: environmental spheres, stakeholders, interaction issues, structuring forces, processes and modes of development. These depict central dimensions of the management function. Whereas environmental spheres and stakeholder expectations have to be analysed with regard to important changes, interaction issues combine manageable matters concerning communication and resource allocation. Structuring forces should be set up to arrange the daily routines coherently, forming the company’s framework for value creating and other activities that are logically combined to consistent processes. Modes of development explain basic patterns of entrepreneurial change processes. The main aim of the St. Galler model is to support sustainable business solutions and organisational development. The University of St. Gallen uses this model as a basic guideline for executive management studies.16

Figure 1-5: Survey of the New St. Gallen Management Model15

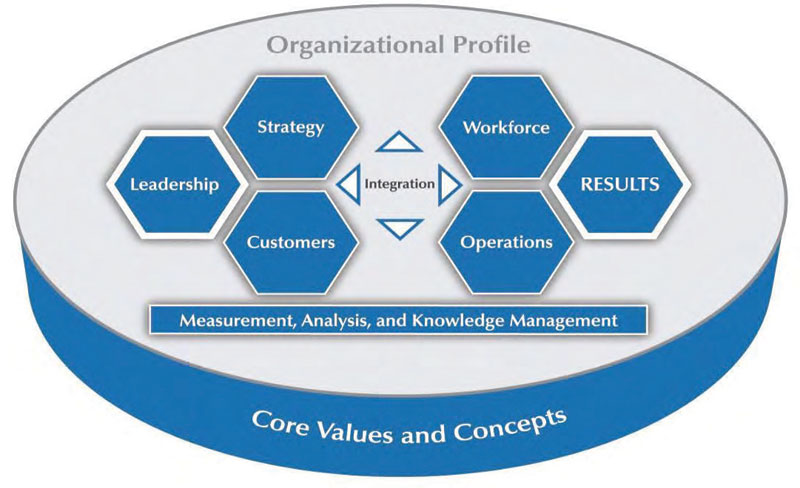

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce. It promotes U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, technology and standards with the help of cooperative programs. The Baldrige Performance Excellence Program is one of those. Driven by a more practical need, criteria were developed in order to evaluate organisations and their competitiveness and to provide guidelines for organisational improvement. The Baldrige criteria and their systems perspective are used for assessing the applications for the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) that is awarded yearly by the U.S. president.17

The requirements of the Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence for business and non-profit organisations are embodied in seven categories, as shown in Figure 1-6. These categories are integrated and connected in the Baldrige framework or systems perspective. Its top basic element is the “Organizational Profile”. It sets the context for the way an organisation operates as it includes its competitive environment, relationships and its strategic situation. Core values and concepts form the basis for the actual Performance Management System. This is first composed of six Baldrige categories: the leadership triad with Leadership (category 1), Strategy (category 2), and Customers (category 3) which sets the organisational direction, and the results triad with Workforce (category 5), Operations (category 6) and Results (category 7). All actions taken by the organisation’s workforce and key operational processes produce its overall performance results. The seventh category forms the system’s foundation, as Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management (category 4) are critical to a factbased, knowledge-driven and effective management system. The central part “integration” stresses the model’s holistic and integrated perspective. The criteria categories are subdivided into overall 17 process and results items, each focusing on a major requirement. Each item consists of one or more areas to address that define more specific requirements. This third level of the whole model is the level that organisations should address in order to explain their particular solutions and approaches when applying for the MBNQA.18

Figure 1-6: Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence Framework 201519

Besides its predominant use in the U.S., the Baldrige model or its equivalent was used for national excellence awards in more than 20 countries worldwide in 2010, for example in Hong Kong and New Zealand.20

The third internationally recognised model is the EFQM Excellence Model. As it represents the red thread through this textbook, it will be explained explicitly in the following chapter 1.3.

VIPs

1.3The Approach of the EFQM Excellence Model

The most successful and widespread holistic management model is the EFQM Excellence Model. Leaders that face an internationalisation challenge are in need of a clear structure of their organisation’s existing management system as well as of ideas for integrating new approaches and different cultures. The EFQM Excellence Model provides through its non-descriptive and structured framework a very good tool for this purpose. Consequently, its building components will be explained in detail in the following subdivisions.21

1.3.1Background Information: The EFQM and its ModelThe EFQM is a global non-for-profit membership foundation, established in 1988 by 14 CEOs of internationally recognised companies (Nestlé, Robert Bosch, Volkswagen et al.) with the goal of developing a management tool for increasing the competitiveness of European organisations. In alignment with its vision of “a world striving for sustainable excellence”22 the EFQM is organiser of the prestigious European Excellence Award that yearly recognises organisations for their sustainable achievements using the EFQM Excellence Model as assessment tool. To date, the EFQM records about 500 international members from many different industries and more than 50 countries.23 Its model is used by over 30 000 organisations in Europe for development and assessment purposes.24 According to a research conducted in 2010, the EFQM Excellence Model or its equivalent is used for national excellence awards in more than 35 countries worldwide, not only in European countries like Germany (Ludwig-Erhard-Preis), Finland, United Kingdom and the Russian Federation but also in Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.25

Due to its background the EFQM Excellence Model was developed from a practical European management perspective. Accordingly, it sets a strong focus on people and sustainability. The inclusion of relevant leadership matters affecting all sorts of global organisations is one of its strong features. Keeping it up-to-date is a major prerequisite for its on-going success; therefore the model is reviewed every 3 years in a rigorous and widespread review process. The latest reviews were carried out with more than 200 representatives from academics, large organisations, EFQM partners and assessors, allowing work groups to comment and test draft versions before the final version was published. The 2013 version of the EFQM Excellence Model now emphasises emerging trends like innovation, risk management and corporate governance. The in-depth revision achieved also a full integration of its main building blocks: the 8 fundamental concepts, the 9 model criteria and the RADAR assessment tool.