Полная версия

The Man Who Created the Middle East: A Story of Empire, Conflict and the Sykes-Picot Agreement

It was a miracle that they ever reached Aleppo, considering that, in the early hours of one morning, the troublesome coachman made an attempt to sabotage the journey by deliberately overturning the coach. ‘The carriage fell on its side with a fearful thud,’ recalled Mark, ‘which was accompanied by a howl of terror from both the dragoman and the cook. The ensuing scene was not without a humorous side. The carriage opened and spat out a curious assortment of men and things on the scrub of the Syrian desert, and it was only when the cook, the bath, the medicine chest and the dragoman had been lifted off me that I was able to survey the scene of the accident. Its appearance reminded me exactly of those admirable pictures drawn in Christmas numbers of illustrated papers of Gretna Green elopements coming to grief in a ditch; luckily however no lady was present, for the language made use of, whether in Arabic or in English, was neither that of the Koran nor Sunday-at-Home.’ When they did finally reach their destination, he found it ‘not altogether a pleasant town’. The natives had a penchant for throwing stones at the hats of foreigners, and often had faces disfigured by ‘Delhi Boils’, which gave them ‘a most sinister expression’. Almost everyone he met, he wrote, who was not a native, ‘seemed to be trying to get away from the place, without success’.23

Six days in Aleppo was quite enough. The party then struck out for Baghdad. Not a day went by without Mark being either amused or frustrated by the character of local people. ‘Their ideas of time and space are nil,’ he noted. ‘If you ask how far away a certain village is, you may be told “one hour”, be the real distance anything from five minutes to twelve hours; or, when you are beginning to feel tired, everyone you ask during the space of a couple of hours may tell you that you are only “seven hours” from your destination. This is really … most annoying.’ At Meskeneh he got his first view of the Euphrates, which did not greatly impress him. ‘Its water is so muddy,’ he noted, ‘that it is impossible to see through a wine-glass filled with it.’24

Meskeneh was the first of a series of military outposts, manned by police or mounted infantry, which lined the high road from Aleppo to Baghdad. They were intended to help keep order in the valley, and to prevent the Anezeh Arabs from crossing the Euphrates, and it was at one of these that Mark now spent each night. When he finally reached the first bridge across the river at Falúja, the final stop before Baghdad, he was amused by what he found there. ‘There is a telegraph wire which crosses the river but there is no telegraph office; the only official in the place is the collector of tolls who dozes most of the day on the bridge; there are no troops; and there is no police station within twenty miles of the bridge. There is therefore nothing to prevent any number of people crossing it … Truly the ways of the Unspeakable are inscrutable.’25

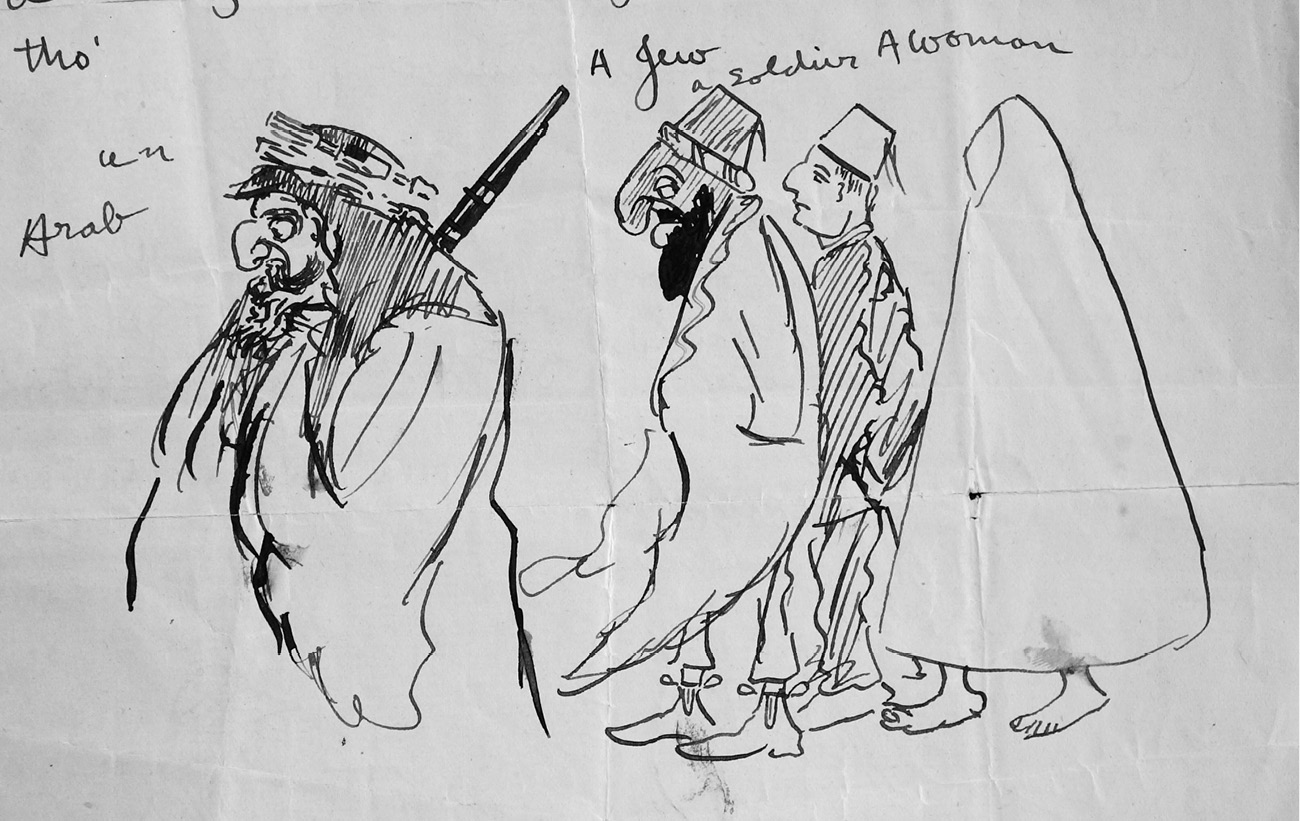

After days of trekking through the desert, the approaching minarets of Baghdad were a wondrous sight: ‘the golden mosque appeared in the distance in the midst of a cluster of palm trees, and … the effect was very beautiful and inspiring’. Once within the city walls, however, although he was impressed by its cleanliness, Mark found little to inspire him, and after spending an enjoyable week staying with the English Resident, he was keen to be on his way to Mosul. Before leaving he penned a letter to Henry Cholmondeley. ‘I have had the most trying weather on my trip, the thermometer has varied in one month from 5º below zero to 90º in the shade, including fogs, snows, sandstorms + 1 week’s incessant rain am going up to Mossoul [sic] and thence to Batoum or Trabzionde [sic] but my route will depend on the state of the country Climactic & Political, it is useless to tell you all that has happened as it fills at least 30 pages of a diary, I can show you the faces of the people tho’ …

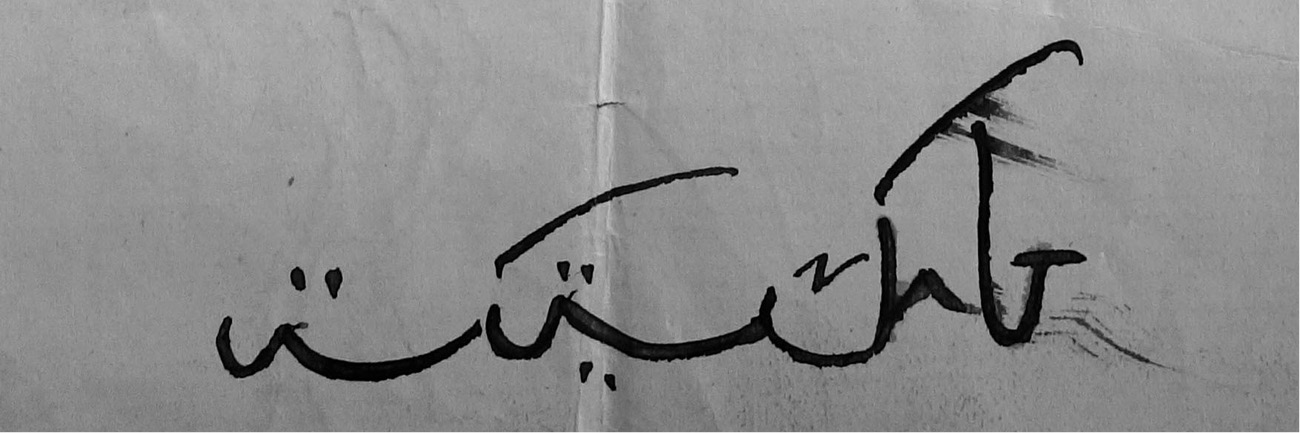

He signed the letter with his Arabic signature, adding the question, ‘How would this do as a check [sic] signature?’26

The journey from Baghdad up to the Russian border turned out to be full of incident, beginning with an encounter with some robbers north-east of Kerkúk. At the time he was travelling with a local governor, or Kaimakám, and his military escort, when they came under fire from some robbers: ‘just as we entered a kind of natural amphitheatre, about two thousand yards broad,’ he recalled, ‘I was handing him my cigarette case, when I was startled by the buzzing of a bullet somewhere overhead followed by the faint “plop” of a rifle on the hill side. I looked round but the kaimakám took a cigarette out of my case and lit it without saying a word. Two other bullets passed overhead and I made some remark about them; he merely said Sont des voleurs Monsieur, and it was only after five more shots had been fired that he took any further notice.’ Mark was impressed by the coolness of the man, ‘who seemed to think no more of the matter than a farm-boy would of crow-scaring’.27

Approaching the town of Mosul, Mark was able to give further rein to his love of underlining the comic and exaggerating the grotesque. ‘The first thing that struck me,’ he wrote, ‘… was a splendid bridge. It is a fine piece of workmanship and has only one fault; it does not cross the river. The engineer commenced building it about a hundred and seventy yards from the bank; he built twenty-four piers, and at the twenty-fourth came to the water. Then after due consideration he thought that he would build the bridge with boats, and these he chained to the end of the masonry. Though this structure is useless as a bridge, it makes an excellent rendezvous for beggars, lepers and sweetmeat vendors.’28

The hardships of the journey increased after Mosul. They were constantly on the lookout for brigands, often mule-rustlers, and as they began to climb up into the mountains, the terrain became more treacherous, with rushing rivers and streams, non-existent roads and tracks that were impassable to anything but mules. It was bitterly cold, but the scenery was magnificent. ‘Overhead was a blue sky, below, the vegetation, such as it was, was green as an emerald,’ wrote Mark. ‘We were among high mountains, whose ruggedness was relieved here and there by clumps of stunted trees. There was snow on the peaks, and down the sides of the mountains streams rushed frantically … In one place we had to pass a very rickety patched-up bridge … Isá when crossing missed his footing and only by the greatest good luck I caught him by the band of his Ulster. Even now it makes me shudder to think of what might have happened to him; for there was a drop of forty feet into a river running like a mill race towards the mass of rocks over which it fell.’29

As Mark and his party drew closer to Bitlis, a strategic Armenian town that was to see 15,000 of its inhabitants massacred by the Turks in July 1916, they began to see more and more snow, which soon became so deep that they had to drag their mounts through it. His plan had been to head straight from here to the Black Sea port of Trebizond, and then home, but when this proved impossible he was forced to go to Van instead. This meant abandoning the muleteers in favour of fifteen man-sledges, each of which could carry a hundred pounds weight of baggage. One of them even had the added weight of Isá, who, fearful of getting cold, had drunk a whole bottle of mastic, the local aniseed-flavoured spirit, and had become so drunk that he had to be tied face-down onto his sledge. Mark was astonished at the strength of the men who pulled these sledges. ‘They kept up a pace of about three and a half miles an hour,’ he noted. ‘They mounted steepish hills with only raw hide lashed under the soles of their feet, and they only rested for five minutes or so every three quarters of an hour. The heavy breathing of the sledge-draggers, the gentle zipping of the sledges as they passed over the snow, the occasional moaning of the drunken man, and the stamping of the cold feet had such an effect on me that a couple of hours after leaving Bitlis I was fast asleep. When I awoke I saw a glorious sunrise; the red flush of the sun on the waters of Lake Van … was beautiful indeed.’30

Crossing Lake Van, the largest lake in Turkey and seventy-four miles across at its widest point, was a hazardous affair. They hired a fifty-ton fishing boat, the Jámi, hired from and captained by its Armenian owner, and though at first all went well, after two hours the wind dropped, and there followed a fearful nocturnal storm during which the sail split, water began to seep in, and the boat began to list alarmingly. The crew, including the skipper, panicked and proved useless, and when Mark tried to get Isá to help him get the ballast straight, he became ‘quite childish, and … screamed “Why you bring me to this debil country? I say bad word for the day I came with you; rubbish boat, rubbish captain, rubbish sea; I say bad word for the religion of this lake!” Then as the boat took a particularly heavy roll, he stood on his feet with a cry of “Our God help us!” (the us being prolonged into a perfect scream) and then collapsed on the side of the boat and lay there vomiting and praying.’31 In the end Mark was reduced to watching over the ballast and bailing by himself. It was, he confessed, ‘one of the most dismal vigils I have ever kept’,32 and Mikhãil, his cook, later confessed, ‘We were as near death as a beggar to poverty.’33

The storm had abated by sunrise, and the shore was in sight. Their plight had been noted from the shore by a Kurdish horseman, who galloped along the cliffs and, with the aid of a stout whip, persuaded a group of Armenians to tow the Jámi to safety. In Van, Mark spent a week with the British consul, Captain Maunsell, before setting out on the slow and arduous trek to the Russian border. The last part of this journey, over a high mountain pass, was almost too much for Isá, the rarefied air giving him heart palpitations. He ‘threw himself on the ground gasping,’ wrote Mark, ‘unable to walk any farther. I tried to carry him on my back but the result was that we both rolled head over heels in the snow; so I got out the medicine chest and gave him a mixture of ginger, brandy and opium …’34 Eight days after finally reaching the Russian border, Mark reached Akstapha, where he boarded the Trans-Caucassian railway bound for Tiflis and Batoum, port of call for the steamer to Constantinople. ‘Isá, Jacob and Michael came to the station and bade me a tearful farewell; and I feel sure that the sorrow they expressed was sincere … we had seen much together and a mutual feeling of respect had grown. Certainly I must confess to a lump in my throat when Isá quavered through the window of the parting train “Masalaam. I pray our God He help you always.” I can only add Inshallah.’35

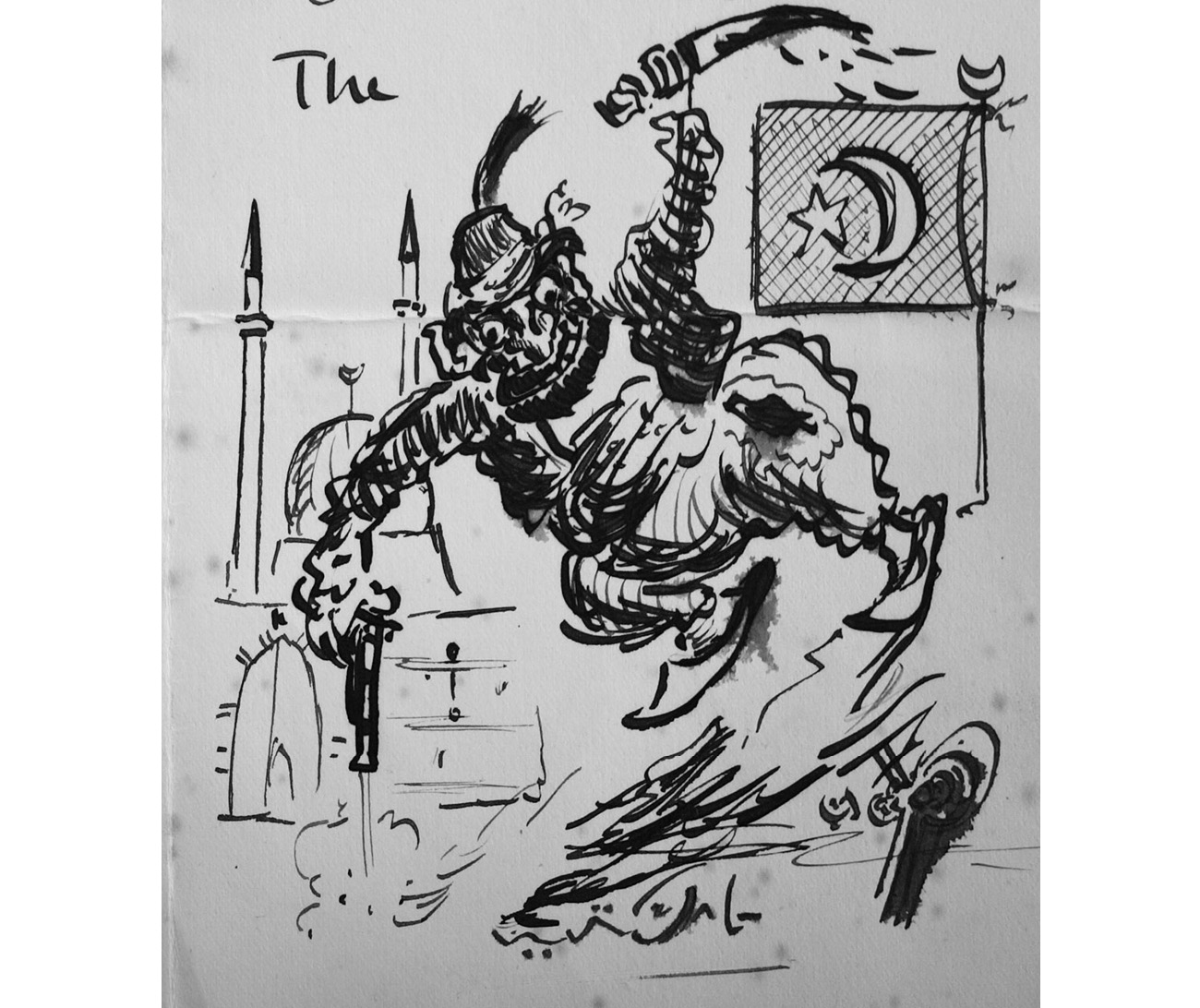

During the time that he had been travelling, Edith may well have been on Mark’s mind, but, he later told her, he ‘neither wrote nor spoke of you to any man’.36 On his return, he began to write to her, his first letters, posted in May 1899, being quite formal, addressing her as ‘Dear Miss Gorst’ and signing off ‘Yours sincerely, Mark Sykes’. By August, she was still ‘Miss Gorst’, while he had given himself a nickname, ‘The Terrible Turk’, that was accompanied by a drawing, and was an allusion to a phrase originally used by Gladstone when condemning the slaughter by the Turks of thousands of Bulgarians in 1876.

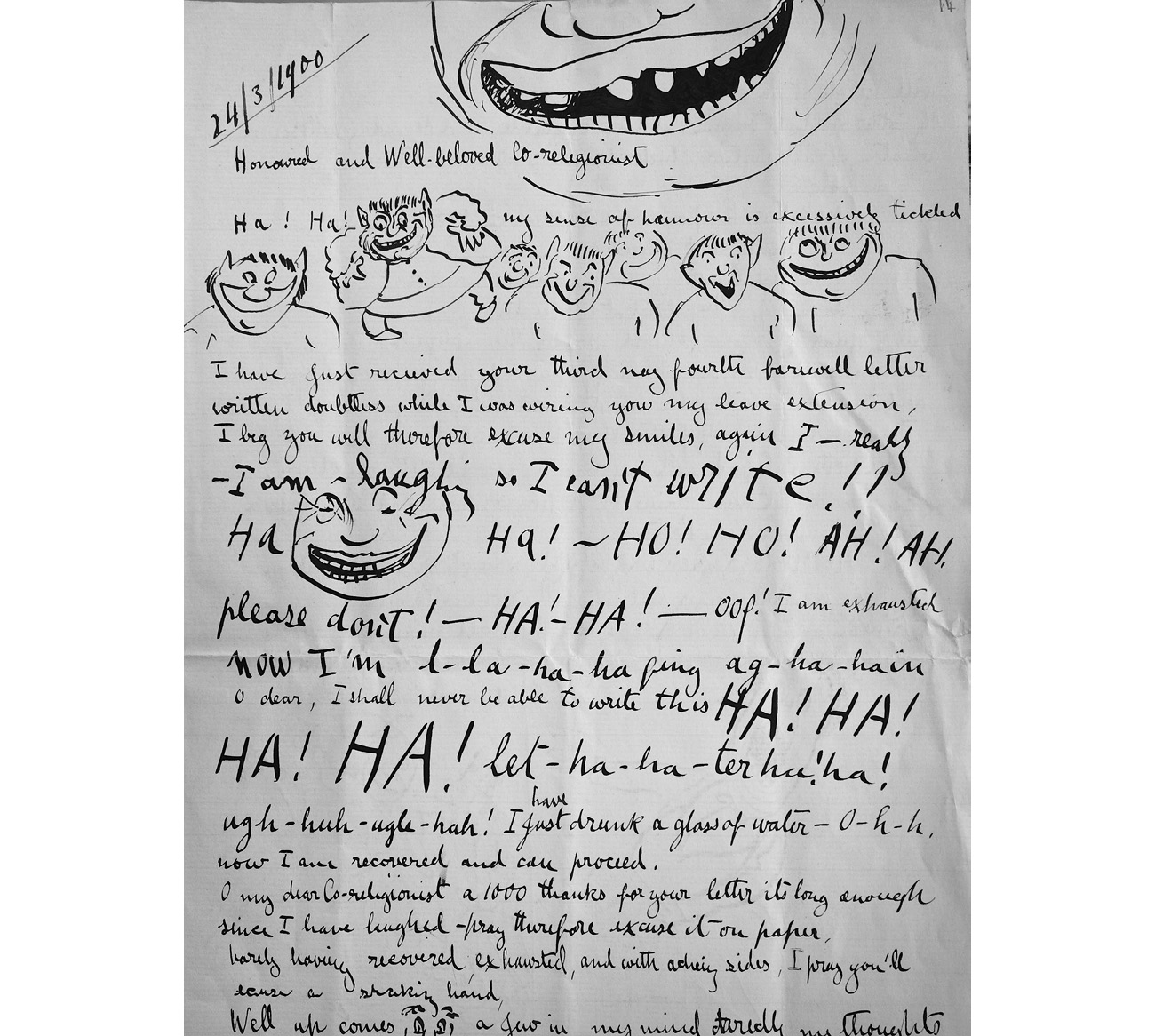

A month later, he was beginning his letters with the words ‘Honourable and Well-Beloved Co-Religionist’ shortly to be abbreviated to ‘H. and W.B. Co-Relig’. As soon as he returned to Cambridge he invited her to dinner. ‘You may remember,’ he said, ‘how … little I spoke at dinner, and then only did I know that I had a real affection for you’, adding, ‘I tell you, if … you had a hump in the middle of your back, a beard like a Jew, eyes that squinted both ways, were bald as a highroad, and had only three black teeth in a mouth like a cauldron, still my affection for you would be the same.’37

However much his thoughts may have been on Edith, he was also fired by a desire to return to the East. ‘I am preparing already for my next journey,’ he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley in August. ‘Entering Turkey by Russia on the Van Side, my rough scheme so far is to buy a complete Equipment gradually & send it to Erivan in small quantities, and then to arrange with Maunsell to send me mules to the frontier, & a certain dragoman I know of there. Then to use those mules & my own equipment for about 5 months, thoroughly visiting Koordistan [sic], presently working down to Baghdad where another dragoman & fresh mules would await, from Baghdad I should work across to Jebel Hauran and thence southward.’38

Such a journey, which was to take up the better part of a year, was expensive, in spite of his attempt to save money by buying his mules outright rather than renting them by the day. He calculated the expenses as follows: ‘Jacob, his servant, £40; Dragoman, £50; Cook, £30; Soldiers, £60; Fodder, £60; Mules, £54; Outfit, including carriage, £200; Muleteers, £30; Cash, £200; and Journey to Turkey and back to London, £35.’ By his very poor mathematics, he reckoned this as adding up to £819, the actual sum being £759, or approximately £82,000 at today’s values. ‘I include, as you see,’ he explained to Cholmondeley, ‘£200 cash for accidents etc, but I count on selling my mules and equipment for at least £150 at the end.’ His intention was to leave England on 15 June 1900, towards the end of the summer term, and end up in Cairo on 10 May 1901, and, with this trip in mind, he intended to devote his next year at Cambridge to the study of the Middle East and its political aspects. ‘I think if I am able to do as I propose,’ he told Cholmondeley, ‘I shall be as well informed on Eastern subjects as many M.P.s who pose as Orientalists.’39

Chapter 4

South Africa

In spite of Professor Browne’s reservations about Mark’s capacity for ‘not learning’, he found him a delightful companion, and he was the perfect choice to tutor him in the history and politics of the Middle East. Though Browne had paid only one visit there, to Persia between 1887 and 1888, he had made good use of his time, travelling through the whole country, and mixing with the company of Persians, mystics and Sufi dervishes. It was a trip that eventually resulted in the publication of his book A year amongst the Persians, as well as numerous articles on subjects such as the rise of the Babi movement. Together he and Mark spent many a happy hour exchanging anecdotes about their travels, while he also did his best to instil a little history into his pupil, as well as attempting to increase his Arabic vocabulary. Their political views, however, were poles apart, with the Professor adopting a Nationalist view, while those of the undergraduate Mark veered towards the Imperialist.

Browne could only do so much tutoring with Mark, whose mind was almost permanently elsewhere. Firstly he was writing up an account of his recent travels with a view to having it published under the title Through Five Turkish Provinces, an ambition that was to be realized the following year. At the same time he was involved in numerous journalistic activities, contributing several pieces, for example, to the Cambridge student magazine The Granta, edited by his old friend George Bowles. In No. 266, for instance, he not only provided the leader, an article on the Militia titled ‘A Sangrado Policy’, but also a skit called ‘The Granta War Trolley’, a cartoon entitled ‘Taste’, the dramatic criticism, and an illustrated limerick. In addition he drew a series of sketches caricaturing various aspects of some of the British newspapers. These included ‘The Pillory of Truth’, ‘The Times’ Sphinx’, and ‘The Imperial Ecstasy of the Daily Mail’.

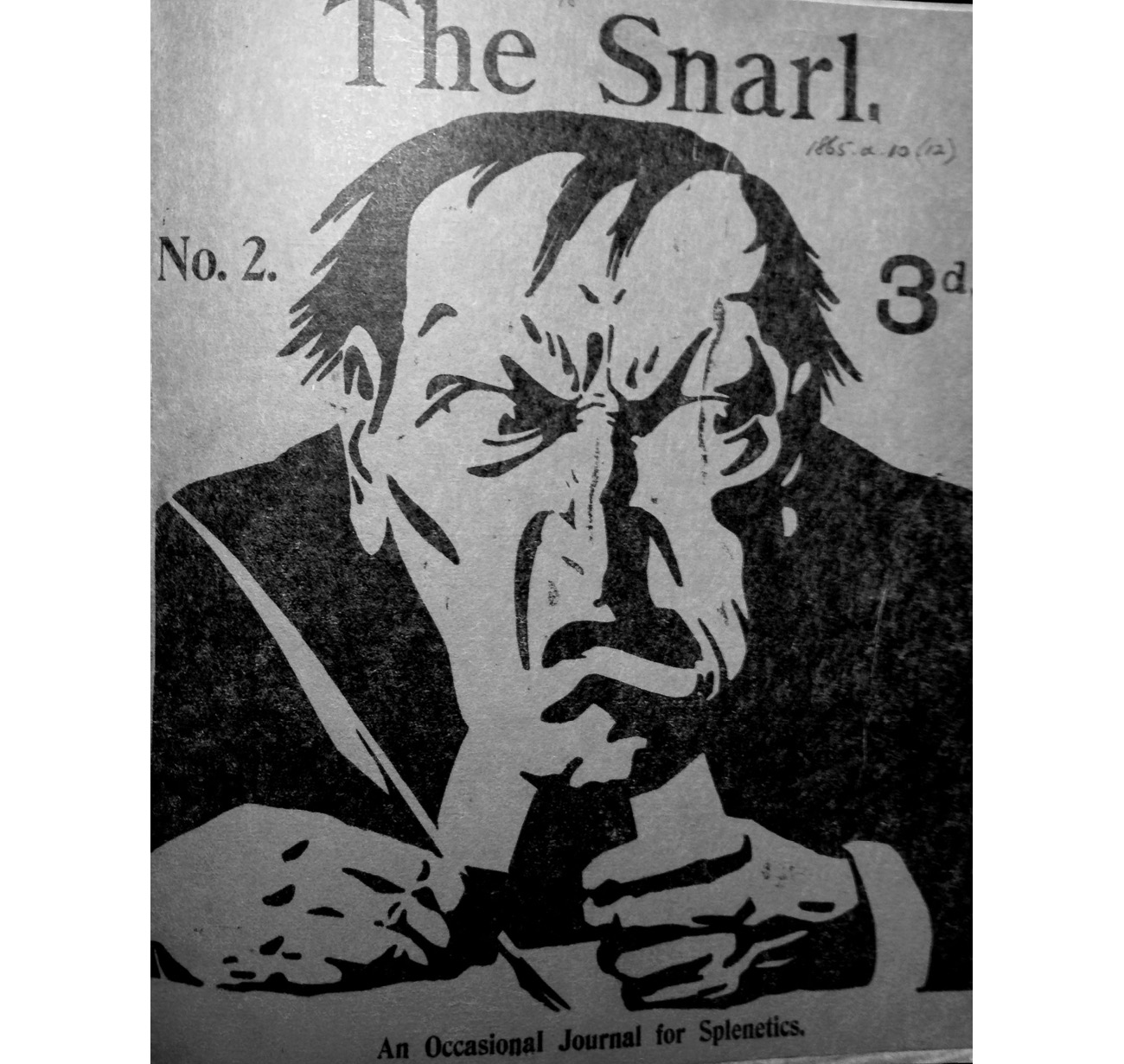

In October he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley, ‘I am starting a newspaper named ‘The Snarl.’ I calculate the loss on three copies about £10. I think the venture is worth trying … it may possibly pay its expenses. I calculate on a certain sale, but at the same time I am paying somewhat for the contributions and also on the necessary advertisement, so please send me a cheque book. I shall not tell my mother I have one, or use it for any other purpose but that of paying contributors … If you think my father will write to stop me, do not tell him as the production is well worth trying & may make me a certain kind of reputation.’1 The Snarl, was co-edited by a Cambridge friend, Edmund Sandars, but appears to have been entirely written by Mark, who also designed and drew the cover. The magazine was subtitled An Occasional Journal for Splenetics, and was a vehicle for him to let off steam on a variety of subjects.

Say what you please – say ‘D—n!’ say ‘H-ll!’

Say ‘botheration!’ Say ‘You Tease!’

Say ‘Don’t!’ Say ‘Dreary me!’ Say ‘Well!’

Say what you please!

Say that the Transvaal’s made of cheese!

Call Chamberlain Ahitophel!

Say women ought to have degrees! –

Say printers might know how to spell!-

Say petits pois means little peas! –

So long as this line ends in l,

Say what you please.2

In the only two issues that were published, he railed against compulsory chapel, attacked the Cambridge Union for degenerating ‘hopelessly and finally into the recognized organ of the great conformist conscience’, described the degree of Master of Arts as being nothing more than ‘the triumph of mediocrity’, and criticized the dons for their ‘narrow-minded ignorance of the world’. In the barely concealed anger and snappish tone of its articles, The Snarl anticipated the modern-day journalism of writers like Will Self and Charlie Booker.

The Cambridge life that Mark was now thoroughly enjoying was rudely interrupted by a conflict which erupted at the outer reaches of the British Empire. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the British had acquired the colony of South Africa to which the government had then actively encouraged British settlers to emigrate. This was the cause of conflict with the original, Afrikaans-speaking, Dutch population, who were known as ‘Boers’, many of whom migrated northwards, on ‘The Great Trek’, where they established two independent Boer republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, both of which were eventually recognized by the British. However, the discovery in the second half of the century of, first of all, diamonds at Kimberley, on the borders of the Orange Free State, and then of vast gold deposits in the Transvaal brought a massive influx of foreigners, ‘uitlanders’, mainly from Britain, who were needed to develop these resources. This caused increasing tensions with the Boers, who began to fear that they would soon become a minority in their own country. In 1899 their worst fears were realized when the British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, demanded full voting rights and representation for all uitlanders living in the Transvaal. It was over this that Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic, declared war on Britain in October 1899.

Having spent much of his childhood playing war games in the park at Sledmere, reading books on the great generals, and studying Vauban’s theories of fortification in the Library, it is not surprising that Mark had an affinity with the military. His heroes were Marshal Saxe, Marshal of France in the reign of Louis XV, and the Emperor Napoleon, as whom he had a penchant for occasionally dressing up.

In his first year at Cambridge, he had decided to apply for a commission in the army, filling in the required E536 form ‘Questionnaire for a candidate for first appointment to a Commission in the Militia, Yeomanry, Cavalry or Volunteers’. Citing his height to be 5 ft 11¾ inches, he had applied to and been accepted for a volunteer militia battalion, the Princess of Wales’s Own Yorkshire Regiment. In this he was following in the footsteps of his ancestor, Sir Christopher Sykes, who in 1798 had raised his own volunteer militia, the Yorkshire Wolds Gentlemen and Yeomanry Cavalry, to help defend the neighbourhood in case of an invasion by Napoleon. Though Mark had done some training with the Regiment in 1898 and 1899, it must still have come as a shock to hear, in the middle of his Michaelmas Term, that they were to be mobilized to serve in South Africa.

‘I now have to go to South Africa’, he wrote to Henry Cholmondeley, ‘which is the most infernal nuisance.’3 It was a nuisance compounded by the fact that his mother’s debtors were once again clamouring for payment and Mark, fearful that his father was immovable in his refusal to pay up, felt himself bound to step in to prevent the whole estate going ‘to the thieves’ shelter’.4 Such a disaster was not inconceivable, since the sums involved were huge, the entire debt being calculated at £120,000.5 ‘[I]f I make myself liable for all these immense sums,’ he wrote to Edith, ‘and no arrangement can be made with my father, with the Estate duty added to all, I shall stand in a somewhat precarious position’. What he found most humiliating, however, was ‘to be constantly arguing on a hypothesis of my father’s death which is to me the most loathsome feature of my repulsive affairs’.6

Over the next two months Mark fought hard to reach a settlement that would be agreeable to all parties, while simultaneously having to be prepared for his leave to be cancelled, and his subsequent departure for South Africa. The number of false starts was marked by the numerous letters of farewell he received from Edith.

In return he kept her entertained with tales of his daily life. He was at Sledmere at the end of March for his coming of age, a very muted affair owing to the war.

These last days have seen me amusing myself by reading old books and arranging a room for me to sit in … I have been receiving piles of congratulatory telegrams and letters concerning my coming of age, mostly of this description …

‘13 Queer St.

Dear Sir,

I hasten to congratulate you on your majority, should you Sir require any small temporary loan from 5 to 20,000 pounds etc, etc …’

I received a silver inkstand from the labourers, a very pretty thing, where at I was very pleased.7

He also amused her with some of the nonsense written about him in the local papers.

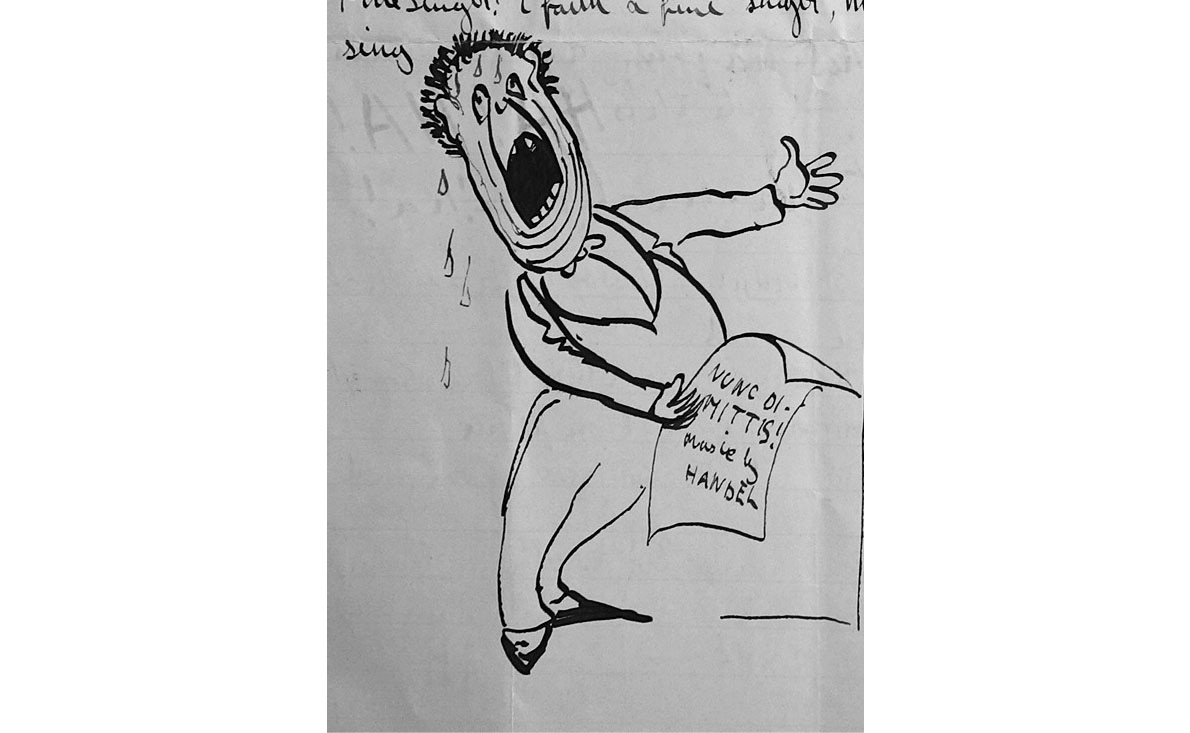

By the way, it never rains but it pours … an extract from the Yorkshire Evening Post. ‘Mr Mark Sykes who has just come of age … is a fine singer and can tell a yarn with anyone.’ Fine Singer!! I’faith a fine singer, that should amuse you. See me sing

or tell a yarn with anyone.8

Back in London, on April Fool’s Day, he took a friend to dinner and a play. ‘I had great fun before the play,’ he told Edith.

I have a little friend not a bad fellow, but an esthete [sic], who is very decadent in fact. Likes Burne-Jones pictures, Aubrey-Beardsley [sic], Ibsen plays, Revolting French Novels, and only likes dining at the Trocadero Restaurant where the food … consists of Truffles and hot pâté de foie gras … I said dine with me at the Marlboro … after a little arguing he agreed, and came expecting rich filth, now for a punishment I ordered