Полная версия

Too Big to Walk

Chinese traditions tell that it was a dragon that sowed the seed of their race. Thousands of years ago, it is said that a tribal leader, Yandi (炎帝), was born out of his mother’s telepathic communication with a mighty dragon. Huangdi (皇帝 the yellow Emperor) and the dragon launched the prelude to the Chinese people when Yandi became the Emperor’s deputy. So the ancient Chinese took to referring to themselves as originating with Yandi and Huangdi, as well as being descendants of the Chinese dragon. The dragon is first recorded in Chinese archæology in the Xinglongwa culture, which dates back more than 7,000 years. Sites excavated from Liangzhu, and from the Yangshao era in Xi’an, include clay pots bearing dragon motifs, and a Xishuipo burial plot in Puyang from the Yangshao people reveals a skeleton of a human flanked by mosaics made from seashells, with a tiger on one side and a dinosaur dragon on the other. The Chinese were the first to record their impression of dinosaur fossils, though they were not alone.3

From ancient Mesopotamia comes an exquisite seal made some 5,500 years ago that seems to show a dinosaur. It is a small cylindrical seal carved from green jasper and shaped like a barrel, which could be rolled across wax or clay to leave an impression. This example was excavated at Uruk in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and is in the collections of The Louvre in Paris. Uruk was once a large and advanced civilization for its time, with impressive buildings and a complex hierarchical social structure. The creatures that were engraved into the surface of their seals often represent domesticated or wild animals, though this example is unusual. It seems to have the appearance of a sauropod dinosaur, and could perhaps have been inspired by a fossil. We know that fossils were known to the ancients, because of writings that date back 1,000 years. The Book of Healing (in Arabic: کتاب الشفاء) was written by the Persian philosopher Ibn Sīnā (Persian: ابن سینا), who is known to present-day Western scholars as Avicenna. His is a remarkable book, covering natural history and mathematics, astronomy and even music, and was written between AD 1010 and 1020. The work is not all his, of course; this was meant as a compendium of current knowledge and contains much information from the ancient Greek writers including Aristotle and Ptolemy, together with the findings of other Persian and Arabic writers. He wrote of fossils as if they were familiar objects, and believed that fossilization occurred when subsidence caused the release of a ‘petrifying virtue’ that subtly transformed substances into stone. He felt that there was nothing surprising about this; it was no more remarkable than the ‘transformation of the waters,’ he wrote.

Notions of the movement of the Earth’s surface and changes with geological time were part of the common currency in the ancient Middle East, though they did not emerge in European philosophy until they were expounded by Magnus Albertus, a physician and polymath, born in 1200, who became widely regarded as the greatest German mind of the Middle Ages. He also wrote of fossils, saying that the rocks around Paris were a rich source of ‘shells shaped like the moon’ that were enveloped by viscous mud and were preserved by the ‘dryness of the stone’.4 For centuries in the West, the occurrence of fossilized seashells on raised ground was taken as evidence of the biblical flood.

Travel now across the world to Cambodia, where the Khmer people live, and at Angkor Wat you will find an ancient image of a dinosaur. There is a stegosaur carved into a wall in the temple of Ta Prohm which was constructed on the orders of the god-king Jayavarman VII and was dedicated in AD 1186. Surviving records show that more than 12,000 people lived in the temple compound at its peak, including 18 high priests and 615 dancers, with another 100,000 villagers dwelling nearby, trading with the temple authorities and providing goods, food and services. Carved into the temple walls are numerous symbolic images, and they were protected by being overgrown with jungle vegetation for centuries so that the building, even though penetrated by massive tree roots, escaped being restored by overeager Europeans. The stegosaur carving has been cited by creationists to show that humans were acquainted with living dinosaurs. The likeness, they say, is anatomically correct – but it isn’t. A real Stegosaurus had a small head and a pointed, spiked tail; the carving at Ta Prohm has a distinctive, larger, head and there is no sign of the typical stegosaurian spiked tail. The dorsal plates are vividly carved, but a living stegosaur had two rows of plates that were more numerous than in the carving. This temple decoration was emphatically not carved by someone who had a living dinosaur as the reference for the image. They could, however, have seen petrified remains. The fossil of a Stegosaurus trapped in limestone strata often reveals only one set of dorsal plates, and it is perfectly reasonable to assume that the head (or the tail) was absent. Stegosaurs had proportionately tiny heads, and the skulls of fossilized dinosaurs are usually missing. Partial fossils are far more abundant than complete dinosaur skeletons, and it is easy to see how an ancient sculptor would have invented a head for his carving. Some present-day amateurs claim that the large plates along the back of this carving ‘more closely resemble leaves’ and they try to assert that the Ta Prohm carving is ‘a boar or rhinoceros against a leafy background’. Like so much scholarly speculation about dinosaurs, this is fanciful. The evidence offers nothing to suggest this is right.5

It has even been alleged that there are no stegosaur fossils in Cambodia by which the carving could have been inspired, but this ignores several realities. First, there are stegosaur skeletons all around the world and they are widespread. Political and academic instability for many years led to a failure for palæontology to develop in Cambodia, and important fossil finds are only now being discovered. Cambodia today is not what it once was. The ancient Khmer empire used to occupy part of Thailand and a great swathe of present-day Vietnam and extended up across today’s Laos. All this is an area now known to be rich in dinosaur fossils including Stegosaurus, and fossils have been recorded at Angkor Wat, near the site of the ancient temple. There are plenty of opportunities for that temple stonecarver to have known a well-preserved fossilized stegosaur skeleton, some 700 years before that dinosaur was first revealed to scientists in the Western world.

There is a stegosaur carving at the Ta Prohm temple in Angkor Wat, Cambodia, which opened in 1186 AD. Some commentators have concluded that the plates along the back are ‘leaves’, but a fossilized skeleton may have been the inspiration.

There are other historic representations of a Stegosaurus. We can travel back across the globe and find an example in the legacy of Father Carlos Crespi Croci, born in Italy in 1891. He studied anthropology at the University of Milan, entered the priesthood, and in 1923 he was sent as a missionary to the small city of Cuenca in Ecuador. He worked tirelessly for the indigenous people, establishing an orphanage and school and helping the poor. Croci is commemorated at the church of Maria Auxiliadora in Cuenca by a statue of him assisting a little child. He died in 1982, and the local residents who knew him remember him with great affection. He also attracted global publicity with a series of curious relics, some of them allegedly coming from North Africa, and was surrounded by allegations of fakery and subterfuge. He was the subject of books and television documentaries that argued the case, and many of his objects were exhibited in a museum. A disastrous fire destroyed the building (and many of the artifacts) in 1962, and controversy has persisted ever since over the fate of the treasures that were recovered from the smoking ruins. One item in that collection, however, was a stone carving that does not seem to be a fake. It shows a creature with plates along its back like a stegosaur, and could conceivably have been inspired by a fossilized skeleton.

Fossil dinosaurs were known to the ancient people of South and Central America. When the conquistador Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca, and his Spanish troops travelled to explore Mexico in 1519, he was presented, not only with gold and precious stones, but with huge fossilized bones. Missionaries who ventured deep into Ecuador and Peru were shown excavations of fossils, and Georges Cuvier (here) referred to them as evidence of creatures now extinct. When Cortés reached Tlaxcalteca, the elders brought out some huge fossilized limb bones, and Bernal Diaz del Castillo, a captain under Cortés, later wrote about these bones resembling the remains of gigantic humans. He said that one thigh bone (femur) was as tall as a man, which is typical of the femur of a sauropod dinosaur. Diaz recorded that the largest of all the bones was sent in a ship back to Spain for the interest of the king, though there are no current records of where it now might be.

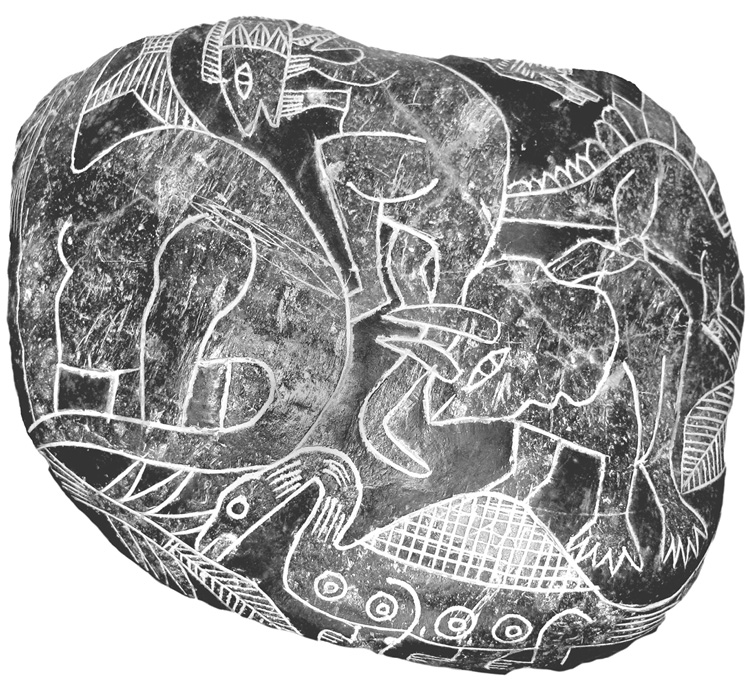

The Ica Stones of Peru, covered with detailed dinosaur carvings, were collected by a doctor who used to purchase them from a farmer, Basilio Uschuya, believing them to be genuine. It later transpired that Uschuya had carved them all himself.

In Mexico you will find a terracotta model reminiscent of an ankylosaur. These tortoise-like dinosaurs lived in the Cretaceous period between 68 and 66 million years ago, and ranged between the size of a tortoise and a small car. Fossils have been found by palæontologists in America and they are very similar to the terracotta model. This curious artifact is approximately 2,000 years old and was made by the artisans of the Jalisco culture, who flourished along the Pacific west coast of Mexico. Stegosaur-like models were also discovered by an expatriate German merchant named Waldemar Julsrud in Acámbaro, Mexico, in July 1944 while out riding his horse. By chance, he spotted some rock carvings and eventually uncovered a range of clay figurines. Julsrud was conversant with Aztec, Toltec, Mayan and Inca artifacts and recorded that these seemed to be different. Julsrud agreed to hire a Mexican farmer, Odilon Tinajero, to dig in the area and offered to pay him one peso (then worth about 12 US cents) for each object he found. Within weeks, he had piles of these figurines.6

Among the models were depictions of stegosaurs and some other dinosaurs. Eventually more than 30,000 of the artifacts were excavated. Considerable controversy surrounded these objects, and scientists dated them using thermoluminescence. These results suggested that they were 4,500 years old, though more recent investigations have claimed that the results were inaccurate, and authorities now insist that the objects are fakes dating from the 1930s. These items were given a museum of their own, and it is open to this day. Most people regard the clay figures as curious fakes,7 though others are convinced that the original dating experiments are valid, and that these are prehistoric relics from an ancient Mexican civilization. There is also a vociferous cohort of enthusiastic supporters of the view that dinosaurs and humans coexisted, and, to these people, the figurines provide the evidence they seek.8

There are other intriguing images that depict humans and dinosaurs together, and some of the carvings from Ica, south of Lima in Peru, even show dinosaurs attacking a human hunter. The images are cut into the surface of volcanic rock of what we now call Ica Stones, rounded nodules of andesite measuring less than 1 foot (30 cm) across. Andesite is a stony mineral that can easily be carved, and these stones purport to depict pre-Columbian scenes and bear symbols from the ancient Inca, Paracas, Nazca and Tiwanaku peoples, as well as the Ica. In the 1930s a Peruvian doctor named Darquea began to collect beautifully carved stones from the town of Ica. His son, Javier Cabrera Darquea, was fascinated by the delicate carvings and began a quest for more. He based his collection on 350 Ica Stones purchased from Carlos and Pablo Soldi, brothers who marketed pre-Columbian artifacts to archæologists and collectors. Through them Javier Darquea met a farmer, Basilio Uschuya, who sold him stones at regular intervals until he had amassed a collection of some 11,000 different examples. He published a book on the message of the stones of Ica, and went on to establish a museum to display some of his impressive collection.9

Dinosaurs fired from clay were found by Waldemar Julsrud in Acámbaro, Mexico, in July 1944. He thought they were from the preclassical Chupicuaro Culture (about 2,000 years ago), but they proved to be forgeries made by a farmer, Odilon Tinajero.

The museum is still there, featuring a range of unmistakable dinosaurs, and many visitors leave impressed by his claims that humans are at least 400 million years old. However, any claim that the artifacts might be authentic disappeared when Uschuya finally conceded that the carvings were fakes. He and a farming friend, Irma Gutierrez de Aparcana, admitted that they had forged the images by copying dinosaur pictures from comics and magazines. A BBC television crew were said to have visited the farmers and paid Uschuya to produce an Ica Stone while they filmed. He cut the patterns with a dentist’s drill and then gave the rock an authentic-looking patina by baking it in cow dung. Many people wondered why he had owned up, but the Peruvian authorities at the time were beginning to enforce the regulated marketing of pre-Columbian artifacts, and – if Uschuya had truly been selling genuine relics – he could have been arrested and put on trial. Conceding that they were fakes was his guarantee against prosecution. Basilio Uschuya was quoted as saying, ‘Carving stones is an easier way of making a living than farming the land,’ while Ken Feder, author of a 2010 book on dubious archæology, wrote: ‘The Ica Stones are not the most sophisticated of the archæological hoaxes, but they certainly rank up there as the most preposterous.’10 It would have been an easy matter to resolve: the microscope would show in an instant whether the images had been engraved by a primitive tool or cut with a dentist’s drill, and microchemical analysis would as easily detect the presence of cow manure on the surface of a stone.

Some similar examples have not been dismissed as fakes. In 1971, at Girifalco in Calabria, southern Italy, a landslip after a 20-hour deluge revealed a cache of artifacts from of a pre-Greek civilization. A lawyer named Mario Tolone Azzariti reported that he had found some terracotta statues, one of which was a model very like a stegosaur. It measures some 7 inches (18 cm) long and shows solid, strong legs (different from those of a present-day lizard). This seems to be a relic of the Stone Age – though I am not aware that it has ever been dated – and may well be the result of inspiration by a fossilized Stegosaurus.

In 1971 in southern Italy, a lawyer named Mario Tolone Azzariti claimed to have found terracotta models, one of which was a like a stegosaur. It measures 7 inches (18 cm) long. Perhaps this was inspired by a fossilized skeleton.

The indigenous peoples of the U.S. knew about fossil dinosaurs for thousands of years. There is an ancient saga among the Delaware people, who inhabited what became New Jersey and Pennsylvania, telling of a party of hunters who returned to their village with a huge, ancient bone which they said had come from a massive monster. This fearsome creature was said to massacre people. A ritual was developed, involving burning tobacco with small fragments of this massive bone, hoping that this would ensure safety from the monster, good hunting for the future, and a long life for all. Fossils found in the area include a range of dinosaurs that we shall encounter later, including Cœlosaurus, Dryptosaurus, Ankylosaurus and Hadrosaurus (subsequently, a hadrosaur was to become the first dinosaur ever to be scientifically investigated in America). As we shall discover later, the Cheyenne people taught that a mythical animal named Ahke once lived in the prairies. These were gigantic god-like bison whose remains had been turned into stone. It seems likely that fossils of the horned dinosaur Triceratops were known since ancient times, and these gave birth to the legend.

Just as the indigenous inhabitants of North America maintain a culture that dates back to prehistory, Stone-Age traditions are also perpetuated by Australian Aborigines. They too have ancient legends about dinosaurs – though there are no fossilized bones to be found. Their dreamtime stories stem from an abundance of dinosaur footprints, notably in northwestern Australia. There are extensive exposures of sandstone on the Dampier Peninsula in the Kimberley region, where innumerable dinosaur footprints are to be found. There are extensive trackways that stretch from Roebuck Bay near Broome north to Cape Leveque; that’s at least 125 miles (200 km). The culture extends inland for at least 100 miles (160 km) across the scrub. So important are these finds that a great swathe of intertidal coastline along the Dampier Peninsula coastline has recently been declared a heritage site.11

The 130-million-year-old rocky strata along the beach, known to geologists as the Broome Sandstone, are marked with countless footprints of three-toed dinosaurs, and these clear tracks have played a part in the local culture for thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of years. The strange footprints in these tracks are clearly recorded in their local legends.12

Australian indigenous people everywhere have an oral culture featuring song cycles that trace in chanted refrains the paths taken by gigantic supernatural beings. Everything in nature is denoted by a specific song – features of the landscape, creatures of the wild, life-sustaining and medicinal flowers, and the stars in the sky – all perpetuating the tradition that existence was predicated upon the legends in these songs.13

The care of both the song cycles and the land – known as Country – rests in the hands of custodians they call Maja, who are selected from the community not because of possessions or family connections, as is common in the West, but purely because of their wisdom and personality. There are different songlines in different places; along the Dampier Peninsula coast they are called ululong, whereas the song cycle that extends east is dabber dabber goon, which reaches past Uluru (which we used to call Ayer’s Rock) and on to Australia’s Pacific coast. At the core of these ancient songs is a mystical being known as Marala, a spirit that laid down the law and established the codes of conduct and morality. The legends about Marala are endless; many of them have been documented by anthropologists, though most remain secret among the tribes and are never vouchsafed to outsiders. One of the songs tells about Marala fighting with Warragunna, the eagle-man, and goes on for hours. Now, it is tempting to dismiss all this as the stuff of legend; as the wild imaginings of a religious people who are now out of their time. Yet their religion has a lot more going for it than any of ours, for they have physical evidence. Marala is a gigantic emu man, and you can see precisely where he walked. There, in the rocks, are the three-toed footprints. There are even some stony giants, weathered in the fierce Sun, that look like petrified monsters. The Aboriginals even know where Marala sat down with Warragunna, because there are the signs of the eagle-man’s feathers clearly preserved in the solid rock. We, with our palæontological insights, know that the footprints of the emu man Marala are actually those of a huge three-toed dinosaur named Megalosauropus. We can also confidently conclude that the feathery impressions of that gigantic eagle are really the fossilized remains of bennettitalean plants, related to the present-day cycads from which we obtain sago, for those leaves really do look like the feathers of a gigantic eagle. The thought processes of Aboriginal people are very different to ours and are hard to follow. A statement by an Aboriginal elder named Lulu from the Gularabulu tribe of the Nyikina people, an ancient community that still lives in the Stone-Age traditions, stated that: ‘The Country now comes from Bugarri-Garriand [dreamtime] and it was made by all the dreamtime ancestors, who left their tracks and statues behind and gave us our law. We still follow that law, which tells us how to look after the Country and how to keep it alive.’14

So here we have an entire way of life and an ancient culture that are based on detailed knowledge of dinosaur footprints and the fossilized remains of Cretaceous plants. Australian Aborigines know their Country intimately, and knew about the remains left by prehistoric monstrous beings thousands of years earlier than we did in the West. The authorities now take these remains seriously. In 2000, an Aborigine from Broome named Michael Latham admitted cutting stegosaur footprints from the sandstone strata, when the tide was low, using an angle-grinder. He was jailed for two years.

The first records from Europeans about the Australian dinosaur tracks were written around 1900 when an immigrant from Ireland, Daisy Bates, spent three months on a mission station in Aboriginal territory. She later returned to the Roebuck Plains Station with her husband and son, and devoted herself to a study of the indigenous coastal communities. She observed many of the areas where footprints were visible. Then, in 1935, Catherine Milner and her young twin daughters discovered some on their own. They wrote later that they had come across the footprints one morning when the tide was low, and they had looked as if ‘whatever had made them had just passed by, so clear and perfect they were.’ Little wonder the tracks were regarded by the Aboriginal people as clear evidence of events.15

The only fossilized remains of actual dinosaurs in Australia are of occasional scattered bones and teeth; yet there is now a growing understanding of the variety of the dinosaur population derived from the fossilized trackways set in stone. They are usually left undisturbed for visitors to enjoy, though this inevitably exposes them to damage. Trackways left by theropod dinosaurs were discovered at the eastern side of Australia when palæontologists first discovered the footprints of a theropod dinosaur in tidal strata at Flat Rocks, Victoria, in 2006. Thousands of scattered bones and teeth have been found in the area, and the dinosaur footprints – measuring about 1 foot (30 cm) across – were left intact for visitors; however, there was no sign pointing them out. In December 2017 someone took a hammer and chisel and chopped out the toes, leaving them scattered nearby. The local Park Ranger, Brian Martin, said: ‘They would need to know exactly where it is to find it. Most people quite easily walk right past it,’ he said. This time the vandals didn’t.

We are beginning to understand how huge some of these monsters were. The massive brachiosaurs which appear so frequently in documentaries and pictures about dinosaurs were colossal creatures measuring about 85 feet (26 metres) long and weighing at least 50 tons, their footprints measuring less than 3 feet (90 cm) in length. Similarly, some unprecedently gigantic footprints were discovered in Mongolia in 2016, each measuring 3 feet 6 inches (1.06 metres) long, which caused considerable surprise among palæontologists. There are Australian huge dinosaur footprints that measure 5 feet 7 inches (1.7 metres) from heel to toe. Nothing so vast has ever been discovered elsewhere.16