Полная версия

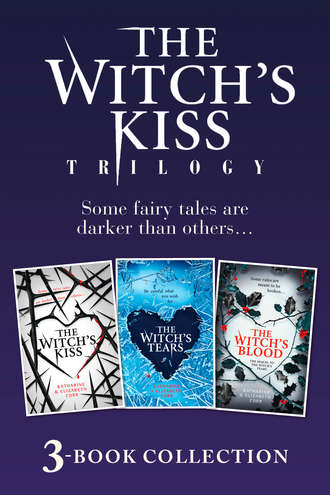

The Witch’s Kiss Trilogy

‘I—’ Merry paused, trying to decide how to explain to Leo; what to tell him. ‘I’m just not ready for this. Like I said, I haven’t cast any spells for nearly a year, apart from accidently, and to just launch into something this big …’ She nodded at the manuscript. ‘We don’t know what’s going to happen, once we figure out how to work that thing. I need more training.’

‘No,’ Leo was shaking his head, ‘what you need is to start dealing with this. Now the manuscript’s … working, you don’t have any choice. Wizard Man and Psycho Boy aren’t going to conveniently take a break while you have remedial witchcraft lessons. You said you were at least going to try—’

‘I know what I said!’ Merry stood up and went to pour the rest of the brandy down the sink. Last night she’d really thought this was all going to turn out to be a mistake, that somehow she was going to be let off the hook. But now …

‘And I am going to try.’ She grabbed the manuscript, folded it up and shoved it back into the box. ‘Just not today.’

‘Fine. Well, you let me know when you’re feeling … up for it.’ Leo shook his head again and shut the lid of the laptop. ‘You’d better phone Gran, by the way. Let her know what’s happened.’

‘Yes, I know.’ Merry picked up the box and marched out of the kitchen.

Right now, she needed to be alone.

Merry switched the light on and looked around her room, half-expecting to see the dark-haired girl standing in the corner, wagging her finger and tutting. But the room was empty. She dropped the trinket box on her desk and threw herself on to the bed. What was Leo’s issue, anyway? Sure, she knew he was just trying to help her, would do anything he could to help her; but at the end of the day this was her problem. She was the one who was going to have to try to kill this Gwydion guy. She was the one who was going to have to try to break the curse …

Just thinking about it made her hands shake.

Of course, being frightened of what she was meant to do would have been easier to deal with if she wasn’t also frightened – terrified – of the magic that was meant to help her do it.

Ha. Not going to tell Leo about that though, are you? Or why you’re frightened of it. He doesn’t know what you did …

Oh shut up. It’s not like I actually killed anyone. Alex is still alive.

Maybe it had been a mistake: reacting the way she had done, swearing off witchcraft completely. What if she had a go at a spell now, when she wasn’t under pressure, when there was no one else around to get hurt if things got out of hand? Her power might respond normally again. Merry took a deep breath, closed her eyes, and brought to mind the words of a charm for finding lost things. It was one of the first formal spells she’d learnt – on the quiet, by sneaking a book out of Gran’s study – and it was easy. She’d used to find it easy, at any rate. You mentally pictured the lost thing, said the words and – abracadabra – you’d end up with a new mental picture of where the lost thing was. She tried it now, carefully, calmly, on an earring she’d dropped somewhere in the house about a month ago. Picturing the earring was simple enough: it was long and dangly, five little crystal-set snowflakes with two silver chain-links between each snowflake. And she remembered all the words of the charm: O Sun by day and Moon by night, shine on the thing I seek, a light; guide my steps and light my mind until that missing thing I find …

But her mind – apart from the image of the earring – remained stubbornly blank.

Oh, great. If I’ve managed to break my powers somehow, are Gran and the coven still going to make me go out there, face Gwydion and his King of Hearts –

Something started rattling. Was the earring stuck at the back of a drawer somewhere? Merry had never had a physical indication of the whereabouts of a lost object before, but her magic had been so unpredictable lately … She jumped off the bed to investigate.

It was just the trinket box, twitching on the desk just like it had been doing the night she and Leo found it.

Merry swore at the box, slammed it up and down on the desktop a few times for good measure, wrapped it up in an old blanket and threw it in the bottom of her wardrobe.

No way was she phoning Gran now: she needed to get her head round what was happening, not be pushed into stuff by a box.

And I’m not going to look up what ‘Eala’ means, either.

So there.

But clearly, she was going to have to do something about that damn manuscript eventually.

The solution came to her overnight. She would ask one of the other witches in the coven – one of the official, properly-trained witches – to have a look at the manuscript for her. If another witch could get the manuscript to work, maybe Gran would change her mind, agree to the coven at least trying to deal with Gwydion without her.

But who to ask?

Not Gran, obviously. And she wasn’t allowed to ask Mum. As she stood in the shower washing her hair, Merry ran through the other people she now knew were in the coven – thanks to the rune-casting episode outside the house the other week. Mrs Knox was another definite no. But the Zara girl … Merry turned up the temperature, letting the hot water ricochet off her tight shoulder muscles. Yes: Zara girl was the same age as her, more or less. She would understand. And it wasn’t like Merry was going to use her as human shield or anything – she just wanted a bit of … help.

Merry had a plan – an achievable, concrete plan. For the first time in twenty-four hours, she smiled.

Unfortunately, it turned out not to be that much of a plan.

The Zara girl – whose name, when Merry tracked her down in the Year 13 common room, turned out to be Flo – had been happy to help. Almost enthusiastic. She said her mum wouldn’t talk about Meredith’s oath, or the curse: just dropped lots of dark hints that had driven her wild with curiosity. So Flo had led the way to a music practice room, chatting all the time, and waited while Merry got the manuscript out of her bag. But then …

Then Merry had pointed to the word, Eala. But Flo hadn’t been able to see it. As far as she could tell, the manuscript was just a completely blank piece of paper. And she’d looked at Merry with such a mixture of doubt and pity in her eyes …

Now Merry was back in her bedroom. She’d spent the evening there, having told Mum and Leo – truthfully – that she had a headache. The failure of her plan, the realisation that Gran had been absolutely literal when she said that only a descendent could face Gwydion – made her just want to curl up under her duvet and hide. If she was asleep – even if she was dreaming – at least she didn’t consciously have to think about what lay ahead of her.

Early the next morning, she was woken by the chimes of the grandfather clock on the landing striking seven. That meant it was actually only six-fifteen; the grandfather clock always ran fast, no matter what anybody did to it. She turned over and tried to get back to sleep.

But she couldn’t settle. As well as the annoyingly loud tick of the clock, there was a strange, pungent smell, almost like …

… burning. Something was on fire. Merry threw the bedclothes back and was halfway out of bed when she saw it.

A circle of flat stones – a hearth? – with a pile of logs burning brightly in the centre. In the middle of her bedroom carpet. As she watched, open-mouthed, the grandfather clock began to chime again, marking the half-hour. But the sound faded, as the room around her dissolved into a different place entirely. Almost entirely: Merry was still sitting on her bed, her hand still clutching the edge of the duvet. But the bed itself was now in the corner of – a cottage, she supposed it was. She could see a loom and a rough wooden cupboard against the far wall, just illuminated by the flames from the hearth. And around the hearth were three figures: the same girl Merry had seen at the station and in the mirror – Meredith? – and two others. One, with black hair and a thin, tear-stained face, was perched next to possibly-Meredith on the edge of a wooden bench. The other, tall and blonde, was standing with her hands on her hips, frowning at the weeping girl. None of them seemed to have noticed the sudden appearance of a stranger and a piece of furniture in their midst.

‘… and it’s as well for you we found you before the wolves did,’ the blonde girl was saying. ‘Wandering off like that, without a word to either of us—’

‘Carys, enough.’ Possibly-Meredith put her arm around the black-haired girl. ‘Nia does not mean to do these things; she does not wish to be … troublesome. You know how it is with those who have the Sight.’

‘I’m sorry, Meredith, I really am,’ Nia murmured.

Merry thought: I was right then. That is Meredith. And those must be her sisters.

‘Well …’ Carys sighed and sat down in an empty chair opposite the other two. ‘We need the truth now, Nia. We all of us know something is wrong, out in the wide world, though we haven’t yet spoken of it. What did you see that drove you up into the woods?’

Nia stared into the flames and the woodsmoke, while the logs crackled and spat. Merry could feel the heat on her face.

‘Two nights ago,’ Nia said, ‘I had a dream. There was a woman, a noble woman, I think, rocking a baby in her arms. I knew her, from somewhere. She looked happy, but there was a shadow over the child, and on his forehead the word king, written in blood.’

‘What did the woman look like?’ Carys asked.

‘The woman had brown hair, almost the colour of hazelnuts, and brown eyes, flecked with gold. And then the woman and the baby disappeared, and I saw a man. He was young and handsome, but he was marked with the same word, and he was holding—’ Nia shut her eyes tight, ‘—no – no, I can’t say—’

‘Nia, dear one,’ Meredith took Nia’s hands in hers. ‘We must know what you saw.’

Nia nodded slowly.

‘The man’s hand was red with blood, so much blood that it ran down his arm and soaked the sleeve of his tunic. He opened his fingers, to show me what he held. It was a heart, Meredith. A human heart. And it was still beating.’

Merry blinked as the scene bled and shifted around her.

She was still sitting on her bed, jammed incongruously into the corner of the cottage. The fire still burnt brightly in the hearth. But now Nia was sitting in the chair, strumming idly on a small wooden lyre. Meredith was crouching over a cooking pot that was hanging from an iron tripod above the fire. The cottage door opened and Carys walked in.

Nia’s fingers stumbled over the strings. Meredith dropped the spoon she was holding and stood up. ‘What have you done to yourself?’

Carys’s hair was in tangles, there were cuts on her hands and a long, bloody welt down the side of her face and neck. ‘You must clean those scratches right away. Nia, where is the chickweed ointment? Did we not—’

Nia was still staring at Carys.

‘It is begun, then?’

Carys nodded.

‘What’s begun?’ Meredith was glancing from Nia to Carys. ‘Carys? What’s begun?’

‘Our preparations, Meredith. For dealing with Gwydion. I have been able to find out where he conceals himself.’

‘No …’ Meredith grasped Carys by the shoulders. ‘What have you done? What did you promise, to gain such knowledge?’

Carys held up a hand, silencing her.

‘Do not ask me, Meredith. I was willing to pay the price that was demanded. We promised we would help, if we could.’

‘She’s right, Meredith.’ Nia came and stood next to Carys. ‘We promised. And who will stop Gwydion, if we do nothing?’

The sisters all turned towards Merry, staring at her as if they were noticing her presence for the first time. But they didn’t seem to be surprised.

‘Who will stop Gwydion, if you do nothing, Merry?’ Meredith asked.

‘Yes,’ Carys was nodding and pointing at her. ‘You must act, Merry.’

Nia stepped forwards.

‘Please, Merry. You are running out of time …’

Merry opened her mouth to reply, to explain – I was going to try, but I’m scared, I’m so scared – but before she could speak a soft chiming started up behind her. She turned away from the three girls, trying to work out where in the cottage the noise was coming from …

… and as she turned, she was back in her bedroom. The cottage, the round hearth with its bright fire – everything had disappeared. The grandfather clock finished chiming the half-hour and fell silent.

No time had passed at all.

Merry collapsed back on to her bed and lay there, shaking. She couldn’t fight it any more. Any of it.

OK, Meredith. You win. I’ll work out how to use the manuscript, fight Jack, kill Gwydion, do whatever you want. Or at least I’ll try.

I promise.

Merry didn’t go to school that day. After Bronwen and Leo had left for work the silence in the house was horrible.

It’s like everything around me is holding its breath, waiting for me to …

She rang Gran.

Gran, thanks to Leo, already knew the manuscript had become active. Merry filled her in on the episode with Flo – there didn’t seem any point in trying to keep it secret. Gran was sympathetic, though she seemed a little hurt by Merry’s decision to ask Flo for help instead of her.

‘I’m not going to force you into anything, darling. And I understand that you’re scared. You’ve a right to be. But if you don’t do something, things are only going to get worse. Have you seen the news this morning?’

‘No. Has there been another attack?’

‘Yes, just the same as before. They’d been stabbed, though once again the hearts weren’t removed; I wish I knew why not. But unfortunately, it was an elderly couple this time. The husband didn’t survive …’

Merry swallowed.

‘OK.’ That was it: people were actually dying now. ‘So, do you want to come over and see the manuscript? So far it just says one word: e – a – l – a.’

‘Eala. Old English for hello. But I won’t be able to read it, darling. Only you, the last of the bloodline, can see what’s written on it.’

‘That’s not true. Leo can see the word too.’

There was a moment of silence on the other end of the phone line.

‘Are you absolutely sure? That doesn’t sound right.’ Another silence. ‘Well … let’s just focus on one thing at a time. I’ll email you some ideas I’ve had about how the manuscript might work, but it may just respond to you automatically.’

‘OK.’ Merry hesitated. She didn’t want the phone call to end: that would mean she had nothing left to do but get on with her ‘destiny’. Gran must have sensed her anxiety.

‘Sweetheart, the manuscript isn’t dangerous, not to you. Work out how to use it, and it will guide you. Now, I’ve been talking to the other coven members about your training—’

‘But what if I can’t do it Gran? What if, when the time comes to face Gwydion, I literally can’t cast a single spell—’

‘Merry, you’re a witch: it’s in your blood. I am certain the magic will be at your disposal, and you’ll know how to use it whether you’ve been trained or not. Think about it. Your ancestors spent hundreds of years preparing for this moment. You just have to take the first step.’

Merry remembered the image that had flashed into her head two days ago.

The first step, off the precipice and into darkness …

Leo was home by early afternoon. The terrible weather – gale force winds now, as well as torrential rain and flooding – meant there wasn’t as much for him to do on the farm as usual. Now he and Merry were sitting at the kitchen table, the manuscript spread out in front of them. There were two words on the page now:

Eala, Merry.

Obviously, the damn thing was making a point.

‘So …’ Leo cleared his throat. ‘What’s the plan?’

‘Gran emailed me a few suggestions. Work through them, I suppose.’ Merry lifted her hands, held them above the manuscript; at least they weren’t trembling too noticeably.

Just get on with it. What’s the worst that can happen?

Er …

She slapped her palms down on the open pages, rushing the words out before she could change her mind: ‘Reveal. Speak. Show.’

Nothing happened.

‘Huh …’ Grabbing the carrier bag from the floor next to her, she tipped the contents out on to the manuscript.

‘What’s that? It looks like—’ Leo poked at the bits and pieces with one finger, ‘—bits of plant, and jewellery.’

Merry held up a spray of dark green needles.

‘Yew – I cut it off the hedge, earlier. It’s for divination and communication; Gran’s idea. This one is sage, for wisdom. That,’ she said, pointing at an earring she’d pinched from Mum’s jewellery box, ‘is turquoise, for psychic abilities. And this,’ she picked up a silver chain with a small purple crystal hanging from it, ‘is amethyst. For intelligence.’

‘I’ve never seen you wear it.’

‘It was a sixteenth birthday present from our so-called father. Why would I want to wear it?’ The necklace, its chain so tarnished it left black marks on her fingers, was the first gift their father had sent her since he left them. Merry remembered the letter that he’d sent with it. A pathetic letter, full of excuses and evasions. She dropped the necklace on to the parchment. ‘I don’t even know why I kept it.’

She arranged the objects in a rough circle around the pages of the manuscript and tried again.

‘Reveal. Speak. Show.’

The yew and the sage burst into flames.

‘Damn—’ Leo put out the fire by throwing his tea over the plants. The manuscript was unharmed, but it was also still blank apart from the greeting. ‘Maybe you need to say the same words, but in Old English? Or – could you just try saying hello back?’

‘Um, I suppose.’ Merry picked up the parchment, held it like a book in front of her, and took a deep breath. ‘Hello, er, manuscript. Do – you – speak – English?’ She caught sight of Leo’s raised eyebrow and flushed. ‘I mean, modern English?’

For a moment there was no response. Then more letters bloomed on the page.

Yes.

Merry glanced at Leo. His eyes were wide.

‘Put it down. See if you have to be touching it. Ask it – ask it something it must know.’

She replaced the parchment on the table.

‘OK. Where is Gwydion?’

The parchment didn’t reply, so Merry picked it up again and repeated the question.

‘Where is Gwydion?’

The wizard Gwydion sleeps still, under the Black Lake.

‘Right. Great. So, what’s next?’ Merry asked.

No response. Again. Merry threw the manuscript back on to the table and leant back in her chair.

‘Any more suggestions?’

Leo pulled the parchment towards him, traced his fingertips over the letters.

‘Dunno. Maybe,’ he wrinkled his forehead, ‘maybe the answers it can give are already set, so you have to know the right question. Try something else.’ He pushed the parchment back to Merry.

She sighed and rolled her eyes, but picked the manuscript up again.

‘OK. Manuscript … how do we stop the King of Hearts stabbing people?’

The servant acts for his master. To end the danger, both must die.

Leo gave her a thumbs up.

‘Right. And what do we need to do, for them to end up dead?’

The puppet hearts must be destroyed.

That didn’t sound so difficult.

‘What are the puppet hearts? Oh – are they the same as the jars of hearts that are in the story?’

No. The puppet hearts are a dark magic, conceived by Gwydion. One heart for the master, and one for the servant. While the puppet hearts exist, Gwydion and his King of Hearts cannot be harmed.

‘Now we’re getting somewhere,’ Leo said. ‘Sounds like the first thing to do is find these hearts.’

Merry nodded.

‘Manuscript, where are the puppet hearts?’

The hearts are hidden, under the lake.

That didn’t sound good. She’d used to swim a lot; for fun and competitively. But her relationship with water, apart from showers and baths, had gone sour since dragging Alex out of the river.

‘OK. So how do we get at the hearts?’

You must go to the lake.

‘Yeah, I think we get the lake part,’ Leo muttered.

Merry was about to ask another question, but more words appeared of their own accord:

This night, the servant will walk abroad after the Moon has risen.

Go to the lake.

* * *

When Mum came home from the gym, Merry retreated to her bedroom. There, she tried asking the manuscript for details of what she was going to have to do at the lake, how she was supposed to retrieve the puppet hearts, whether she was meant to try to kill the King of Hearts as soon as she saw him. But it just kept repeating itself: Go to the lake.

Leo knocked on the door and came in. ‘You OK?’

She shrugged.

‘Well,’ he sat on her bed and picked up the ancient, misshapen teddy bear that still lived on her pillow, ‘at least we have a plan now. Hopefully, once we get to the lake, the manuscript will give us more instructions. We’ll be able to finish this thing tonight and everything will go back to normal.’

‘Yeah. Maybe.’ Merry paused. ‘What do you mean, we?’

‘There’s no way you’re doing this alone. I’m coming with you.’

‘But Gran said only one witch could enter Gwydion’s evil lair, or whatever he’s calling it. You heard her.’

‘Screw what Gran said. You’re going to be in charge, but every hero needs an assistant, a – a – ’

‘Sidekick?’

Leo scowled.

‘I was thinking more like a second-in-command, a wingman, actually. Besides, we don’t know yet whether this is going to involve any actual lair-entering. And if it does I’m not a witch, am I? I won’t even register on Gwydion’s magic meter.’

Merry hesitated. It was so tempting, but –

‘No, Leo, it’s too dangerous. I won’t let you.’

Leo stretched his legs out and clasped his hands behind his head.

‘But you don’t understand, little sister. Either you agree that we’re doing this together, or I tell Mum everything that’s happened so far. Then Mum will probably go nuts, you’ll be grounded, and Gwydion will end up killing us all anyway.’ He smiled. ‘Your choice, of course. I’ll just pop downstairs and tell her now, shall I?’

‘Are you completely insane?’ Merry bit her lip. He was bluffing. Probably. ‘When this is all over, you’re dead.’ She made an exaggerated throat-cutting gesture with her forefinger. ‘So dead.’

‘If we’re both still alive when this is over, I’m willing to bet you’ll forgive me.’ He winked and grinned at her.

Merry couldn’t help laughing.

‘OK. You make a good point, my lovely assistant.’ She tilted her head and gazed at him appraisingly. ‘I wonder how you’d look in a sparkly leotard? Maybe with, like, an artistically-positioned feather boa …’

‘That’s something neither of us will ever know.’ Leo got up to leave. ‘You should call Gran. I’ll try to figure out how to get out of the house without making Mum suspicious.’

The conversation with Gran was surreal. Gran was happy that the manuscript was responding, and reassured Merry again that all she had to do – all – was follow the instructions; everything was bound to turn out fine. Then she said she would alert the rest of the coven so they could make sure the area around the lake was clear of ‘civilians’, by which she meant non-witches. Initially, Merry assumed this communication would be done by magic, possibly involving owls or bats, but no: Gran was going to text everyone and put a message up on the coven’s Facebook page.