полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

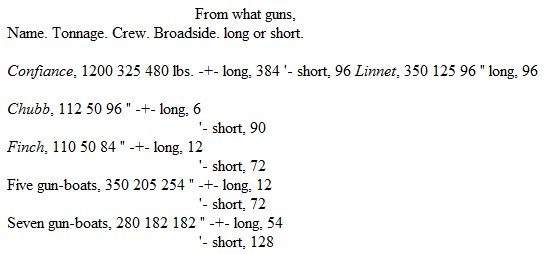

DOWNIE'S SQUADRON.

In all, 16 vessels, of about 2,402 tons, with 937 men, [Footnote: About; there were probably more rather than less.] and a total of 92 guns, throwing at a broadside 1,192 lbs., 660 from long and 532 from short pieces.

These are widely different from the figures that appear in the pages of most British historians, from Sir Archibald Alison down and up. Thus, in the "History of the British Navy," by C. D. Yonge (already quoted), it is said that on Lake Champlain "our (the British) force was manifestly and vastly inferior, * * * their (the American) broadside outweighing ours in more than the proportion of three to two, while the difference in their tonnage and in the number of their crews was still more in their favor." None of these historians, or quasi-historians, have made the faintest effort to find out the facts for themselves, following James' figures with blind reliance, and accordingly it is only necessary to discuss the latter. This reputable gentleman ends his account ("Naval Occurrences," p. 424) by remarking that Macdonough wrote as he did because "he knew that nothing would stamp a falsehood with currency equal to a pious expression, * * * his falsehoods equalling in number the lines of his letter." These remarks are interesting as showing the unbiassed and truthful character of the author, rather than for any particular weight they will have in influencing any one's judgment on Commodore Macdonough. James gives the engaged force of the British as "8 vessels, of 1,426 tons, with 537 men, and throwing 765 lbs. of shot." To reduce the force down to this, he first excludes the Finch, because she "grounded opposite an American battery before the engagement commenced," which reads especially well in connection with Capt. Pring's official letter: "Lieut. Hicks, of the Finch, had the mortification to strike on a reef of rocks to the eastward of Crab Island about the middle of the engagement." [Footnote: The italics are mine. The letter is given in full in the "Naval Chronicle."] What James means cannot be imagined; no stretch of language will convert "about the middle of" into "before." The Finch struck on the reef in consequence of having been disabled and rendered helpless by the fire from the Ticonderoga. Adding her force to James' statement (counting her crew only as he gives it), we get 9 vessels, 1,536 tons, 577 men, 849 lbs. of shot. James also excludes five gun-boats, because they ran away almost as soon as the action commenced (vol. vi, p. 501). This assertion is by no means equivalent to the statement in Captain Pring's letter "that the flotilla of gun-boats had abandoned the object assigned to them," and, if it was, it would not warrant his excluding the five gun-boats. Their flight may have been disgraceful, but they formed part of the attacking force nevertheless; almost any general could say that he had won against superior numbers if he refused to count in any of his own men whom he suspected of behaving badly. James gives his 10 gun-boats 294 men and 13 guns (two long 24's, five long 18's, six 32-pound carronades), and makes them average 45 tons; adding on the five he leaves out, we get 14 vessels, of 1,761 tons, with 714 men, throwing at a broadside 1,025 lbs. of shot (591 from long guns, 434 from carronades). But Sir George Prevost, in the letter already quoted, says there were 12 gun-boats, and the American accounts say more. Supposing the two gun-boats James did not include at all to be equal respectively to one of the largest and one of the smallest of the gun-boats as he gives them ("Naval Occurrences," p. 417); that is, one to have had 35 men, a long 24, and a 32-pound carronade, the other, 25 men and a 32-pound carronade, we get for Downie's force 16 vessels, of 1,851 tons, with 774 men, throwing at a broadside 1,113 lbs. of shot (615 from long guns, 498 from carronades). It must be remembered that so far I have merely corrected James by means of the authorities from which he draws his account—the official letters of the British commanders. I have not brought up a single American authority against him, but have only made such alterations as a writer could with nothing whatever but the accounts of Sir George Prevost and Captain Pring before him to compare with James. Thus it is seen that according to James himself Downie really had 774 men to Macdonough's 882, and threw at a broadside 1,113 lbs. of shot to Macdonough's 1,194 lbs. James says ("Naval Occurrences," pp. 410, 413): "Let it be recollected, no musketry was employed on either side," and "The marines were of no use, as the action was fought out of the range of musketry"; the 106 additional men on the part of the Americans were thus not of much consequence, the action being fought at anchor, and there being men enough to manage the guns and perform every other duty. So we need only attend to the broadside force. Here, then, Downie could present at a broadside 615 lbs. of shot from long guns to Macdonough's 480, and 498 lbs. from carronades to Macdonough's 714; or, he threw 135 lbs. of shot more from his long guns, and 216 less from his carronades. This is equivalent to Downie's having seven long 18's and one long 9, and Macdonough's having one 24-pound and six 32-pound carronades. A 32-pound carronade is not equal to a long 18; so that even by James' own showing Downie's force was slightly the superior.

Thus far, I may repeat, I have corrected James solely by the evidence of his own side; now I shall bring in some American authorities. These do not contradict the British official letters, for they virtually agree with them; but they do go against James' unsupported assertions, and, being made by naval officers of irreproachable reputation, will certainly outweigh them. In the first place, James asserts that on the main-deck of the Confiance but 13 guns were presented in broadside, two 32-pound carronades being thrust through the bridle- and two others through the stern-ports; so he excludes two of her guns from the broadside. Such guns would have been of great use to her at certain stages of the combat, and ought to be included in the force. But besides this the American officers positively say that she had a broadside of 15 guns. Adding these two guns, and making a trifling change in the arrangement of the guns in the row-galleys, we get a broadside of 1,192 lbs., exactly as I have given it above. There is no difficulty in accounting for the difference of tonnage as given by James and by the Americans, for we have considered the same subject in reference to the battle of Lake Erie. James calculates the American tonnage as if for sea-vessels of deep holds, while, as regards the British vessels, he allows for the shallow holds that all the lake craft had; that is, he gives in one the nominal, in the other the real, tonnage. This fully accounts for the discrepancy. It only remains to account for the difference in the number of men. From James we can get 772. In the first place, we can reason by analogy. I have already shown that, as regards the battle of Lake Erie, he is convicted (by English, not by American, evidence) of having underestimated Barclay's force by about 25 per cent. If he did the same thing here, the British force was over 1,000 strong, and I have no doubt that it was. But we have other proofs. On p. 417 of the "Naval Occurrences" he says the complement of the four captured British vessels amounted to 420 men, of whom 54 were killed in action, leaving 366 prisoners, including the wounded. But the report of prisoners, as given by the American authorities, gives 369 officers and seamen unhurt or but slightly wounded, 57 wounded men paroled, and other wounded whose number was unspecified. Supposing this number to have been 82, and adding 54 dead, we would get in all 550 men for the four ships, the number I have adopted in my list. This would make the British wounded 129 instead of 116, as James says: but neither the Americans nor the British seem to have enumerated all their wounded in this fight. Taking into account all these considerations, it will be seen that the figures I have given are probably approximately correct, and, at any rate, indicate pretty closely the relative strength of the two squadrons. The slight differences in tonnage and crews (158 tons and 55 men, in favor of the British) are so trivial that they need not be taken into account, and we will merely consider the broadside force. In absolute weight of metal the two combatants were evenly matched—almost exactly;—but whereas from Downie's broadside of 1,192 lbs. 660 were from long and 532 from short guns, of Macdonough's broadside of 1,194 lbs., but 480 were from long and 714 from short pieces. The forces were thus equal, except that Downie opposed 180 lbs. from long guns to 182 from carronades; as if 10 long 18's were opposed to ten 18-pound carronades. This would make the odds on their face about 10 to 9 against the Americans; in reality they were greater, for the possession of the Confiance was a very great advantage. The action is, as regards metal, the exact reverse of those between Chauncy and Yeo. Take, for example, the fight off Burlington on Sept. 28, 1813. Yeo's broadside was 1,374 lbs. to Chauncy's 1,288; but whereas only 180 of Yeo's was from long guns, of Chauncy's but 536 was from carronades. Chauncy's fleet was thus much the superior. At least we must say this: if Macdonough beat merely an equal force, then Yeo made a most disgraceful and cowardly flight before an inferior foe; but if we contend that Macdonough's force was inferior to that of his antagonist, then we must admit that Yeo's was in like manner inferior to Chauncy's. These rules work both ways. The Confiance was a heavier vessel than the Pike, presenting in broadside one long 24- and three 32-pound carronades more than the latter. James (vol. vi, p. 355) says: "The Pike alone was nearly a match for Sir James Yeo's squadron," and Brenton says (vol. ii, 503): "The General Pike was more than a match for the whole British squadron." Neither of these writers means quite as much as he says, for the logical result would be that the Confiance alone was a match for all of Macdonough's force. Still it is safe to say that the Pike gave Chauncy a great advantage, and that the Confiance made Downie's fleet much superior to Macdonough's.

Macdonough saw that the British would be forced to make the attack in order to get the control of the waters. On this long, narrow lake the winds usually blow pretty nearly north or south, and the set of the current is of course northward; all the vessels, being flat and shallow, could not beat to windward well, so there was little chance of the British making the attack when there was a southerly wind blowing. So late in the season there was danger of sudden and furious gales, which would make it risky for Downie to wait outside the bay till the wind suited him; and inside the bay the wind was pretty sure to be light and baffling. Young Macdonough (then but 28 years of age) calculated all these chances very coolly and decided to await the attack at anchor in Plattsburg Bay, with the head of his line so far to the north that it could hardly be turned; and then proceeded to make all the other preparations with the same foresight. Not only were his vessels provided with springs, but also with anchors to be used astern in any emergency. The _Saratoga _was further prepared for a change of wind, or for the necessity of winding ship, by having a kedge planted broad off on each of her bows, with a hawser and preventer hawser (hanging in bights under water) leading from each quarter to the kedge on that side. There had not been time to train the men thoroughly at the guns; and to make these produce their full effect the constant supervision of the officers had to be exerted. The British were laboring under this same disadvantage, but neither side felt the want very much, as the smooth water, stationary position of the ships, and fair range, made the fire of both sides very destructive.

Plattsburg Bay is deep and opens to the southward; so that a wind which would enable the British to sail up the lake would force them to beat when entering the bay. The east side of the mouth of the bay is formed by Cumberland Head; the entrance is about a mile and a half across, and the other boundary, southwest from the Head, is an extensive shoal, and a small, low island. This is called Crab Island, and on it was a hospital and one six-pounder gun, which was to be manned in case of necessity by the strongest patients. Macdonough had anchored in a north-and-south line a little to the south of the outlet of the Saranac, and out of range of the shore batteries, being two miles from the western shore. The head of his line was so near Cumberland Head that an attempt to turn it would place the opponent under a very heavy fire, while to the south the shoal prevented a flank attack. The Eagle lay to the north, flanked on each side by a couple of gun-boats; then came the Saratoga, with three gun-boats between her and the Ticonderoga, the next in line; then came three gun-boats and the Preble. The four large vessels were at anchor; the galleys being under their sweeps and forming a second line about 40 yards back, some of them keeping their places and some not doing so. By this arrangement his line could not be doubled upon, there was not room to anchor on his broadside out of reach of his carronades, and the enemy was forced to attack him by standing in bows on.

The morning of September 11th opened with a light breeze from the northeast. Downie's fleet weighed anchor at daylight, and came down the lake with the wind nearly aft, the booms of the two sloops swinging out to starboard. At half-past seven, [Footnote: The letters of the two commanders conflict a little as to time, both absolutely and relatively. Pring says the action lasted two hours and three quarters, the American accounts, two hours and twenty minutes. Pring says it began at 8.00; Macdonough says a few minutes before nine, etc. I take the mean time.] the people in the ships could see their adversaries' upper sails across the narrow strip of land ending in Cumberland Head, before the British doubled the latter. Captain Downie hove to with his four large vessels when he had fairly opened the Bay, and waited for his galleys to overtake him. Then his four vessels filled on the starboard tack and headed for the American line, going abreast, the Chubb to the north, heading well to windward of the Eagle, for whose bows the Linnet was headed, while the Confiance was to be laid athwart the hawse of the Saratoga; the Finch was to leeward with the twelve gun-boats, and was to engage the rear of the American line.

As the English squadron stood bravely in, young Macdonough, who feared his foes not at all, but his God a great deal, knelt for a moment, with his officers, on the quarter-deck; and then ensued a few minutes of perfect quiet, the men waiting with grim expectancy for the opening of the fight. The Eagle spoke first with her long 18's, but to no effect, for the shot fell short. Then, as the Linnet passed the Saratoga, she fired her broadside of long 12's, but her shot also fell short, except one that struck a hen-coop which happened to be aboard the Saratoga. There was a game cock inside, and, instead of being frightened at his sudden release, he jumped up on a gun-slide, clapped his wings, and crowed lustily. The men laughed and cheered; and immediately afterward Macdonough himself fired the first shot from one of the long guns. The 24-pound ball struck the Confiance near the hawse-hole and ranged the length of her deck, killing and wounding several men. All the American long guns now opened and were replied to by the British galleys.

The Confiance stood steadily on without replying. But she was baffled by shifting winds, and was soon so cut up, having both her port bow-anchors shot away, and suffering much loss, that she was obliged to port her helm and come to while still nearly a quarter of a mile distant from the Saratoga. Captain Downie came to anchor in grand style,—securing every thing carefully before he fired a gun, and then opening with a terribly destructive broadside. The Chubb and Linnet stood farther in, and anchored forward the Eagle's beam. Meanwhile the Finch got abreast of the Ticonderoga, under her sweeps, supported by the gun-boats. The main fighting was thus to take place between the vans, where the Eagle, Saratoga, and six or seven gun-boats were engaged with the Chubb, Linnet, Confiance, and two or three gun-boats; while in the rear, the Ticonderoga, the Preble, and the other American galleys engaged the Finch and the remaining nine or ten English galleys. The battle at the foot of the line was fought on the part of the Americans to prevent their flank being turned, and on the part of the British to effect that object. At first, the fighting was at long range, but gradually the British galleys closed up, firing very well. The American galleys at this end of the line were chiefly the small ones, armed with one 12-pounder apiece, and they by degrees drew back before the heavy fire of their opponents. About an hour after the discharge of the first gun had been fired the Finch closed up toward the Ticonderoga, and was completely crippled by a couple of broadsides from the latter. She drifted helplessly down the line and grounded near Crab Island; some of the convalescent patients manned the six-pounder and fired a shot or two at her, when she struck, nearly half of her crew being killed or wounded. About the same time the British gun-boats forced the Preble out of line, whereupon she cut her cable and drifted inshore out of the fight. Two or three of the British gun-boats had already been sufficiently damaged by some of the shot from the Ticonderoga's long guns to make them wary; and the contest at this part of the line narrowed down to one between the American schooner and the remaining British gun-boats, who combined to make a most determined attack upon her. So hastily had the squadron been fitted out that many of the matches for her guns were at the last moment found to be defective. The captain of one of the divisions was a midshipman, but sixteen years old, Hiram Paulding. When he found the matches to be bad he fired the guns of his section by having pistols flashed at them, and continued this through the whole fight. The Ticonderoga's commander, Lieut. Cassin, fought his schooner most nobly. He kept walking the taffrail amidst showers of musketry and grape, coolly watching the movements of the galleys and directing the guns to be loaded with canister and bags of bullets, when the enemy tried to board. The British galleys were handled with determined gallantry, under the command of Lieutenant Bell. Had they driven off the Ticonderoga they would have won the day for their side, and they pushed up till they were not a boat-hook's length distant, to try to carry her by boarding; but every attempt was repulsed and they were forced to draw off, some of them so crippled by the slaughter they had suffered that they could hardly man the oars.

Meanwhile the fighting at the head of the line had been even fiercer. The first broadside of the Confiance, fired from 16 long 24's, double shotted, coolly sighted, in smooth water, at point-blank range, produced the most terrible effect on the Saratoga. Her hull shivered all over with the shock, and when the crash subsided nearly half of her people were seen stretched on deck, for many had been knocked down who were not seriously hurt. Among the slain was her first lieutenant, Peter Gamble; he was kneeling down to sight the bow-gun, when a shot entered the port, split the quoin, and drove a portion of it against his side, killing him without breaking the skin. The survivors carried on the fight with undiminished energy. Macdonough himself worked like a common sailor, in pointing and handling a favorite gun. While bending over to sight it a round shot cut in two the spanker boom, which fell on his head and struck him senseless for two or three minutes; he then leaped to his feet and continued as before, when a shot took off the head of the captain of the gun and drove it in his face with such a force as to knock him to the other side of the deck. But after the first broadside not so much injury was done; the guns of the Confiance had been levelled to point-blank range, and as the quoins were loosened by the successive discharges they were not properly replaced, so that her broadsides kept going higher and higher and doing less and less damage. Very shortly after the beginning of the action her gallant captain was slain. He was standing behind one of the long guns when a shot from the Saratoga struck it and threw it completely off the carriage against his right groin, killing him almost instantly. His skin was not broken; a black mark, about the size of a small plate, was the only visible injury. His watch was found flattened, with its hands pointing to the very second at which he received the fatal blow. As the contest went on the fire gradually decreased in weight, the guns being disabled. The inexperience of both crews partly caused this. The American sailors overloaded their carronades so as to very much destroy the effect of their fire; when the officers became disabled, the men would cram the guns with shot till the last projected from the muzzle. Of course, this lessened the execution, and also gradually crippled the guns. On board the Confiance the confusion was even worse: after the battle the charges of the guns were drawn, and on the side she had fought one was found with a canvas bag containing two round of shot rammed home and wadded without any powder; another with two cartridges and no shot; and a third with a wad below the cartridge.

At the extreme head of the line the advantage had been with the British. The Chubb and Linnet had begun a brisk engagement with the Eagle and American gun-boats. In a short time the Chubb had her cable, bowsprit, and main-boom shot away, drifted within the American lines, and was taken possession of by one of the Saratoga's midshipmen. The Linnet paid no attention to the American gunboats, directing her whole fire against the Eagle, and the latter was, in addition, exposed to part of the fire of the Confiance. After keeping up a heavy fire for a long time her springs were shot away, and she came up into the wind, hanging so that she could not return a shot to the well-directed broadsides of the Linnet. Henly accordingly cut his cable, started home his top-sails, ran down, and anchored by the stern between and inshore of the Confiance and Ticonderoga, from which position he opened on the Confiance. The Linnet now directed her attention to the American gun-boats, which at this end of the line were very well fought, but she soon drove them off, and then sprung her broadside so as to rake the Saratoga on her bows.

Macdonough by this time had his hands full, and his fire was slackening; he was bearing the whole brunt of the action, with the frigate on his beam and the brig raking him. Twice his ship had been set on fire by the hot shot of the Confiance; one by one his long guns were disabled by shot, and his carronades were either treated the same way or else rendered useless by excessive overcharging. Finally but a single carronade was left in the starboard batteries, and on firing it the naval-bolt broke, the gun flew off the carriage and fell down the main hatch, leaving the Commodore without a single gun to oppose to the few the Confiance still presented. The battle would have been lost had not Macdonough's foresight provided the means of retrieving it. The anchor suspended astern of the Saratoga was let go, and the men hauled in on the hawser that led to the starboard quarter, bringing the ship's stern up over the kedge. The ship now rode by the kedge and by a line that had been bent to a bight in the stream cable, and she was raked badly by the accurate fire of the Linnet. By rousing on the line the ship was at length got so far round that the aftermost gun of the port broadside bore on the Confiance. The men had been sent forward to keep as much out of harm's way as possible, and now some were at once called back to man the piece, which then opened with effect. The next gun was treated in the same manner; but the ship now hung and would go no farther round. The hawser leading from the port quarter was then got forward under the bows and passed aft to the starboard quarter, and a minute afterward the ship's whole port battery opened with fatal effect. The Confiance meanwhile had also attempted to round. Her springs, like those of the Linnet, were on the starboard side, and so of course could not be shot away as the Eagle's were; but, as she had nothing but springs to rely on, her efforts did little beyond forcing her forward, and she hung with her head to the wind. She had lost over half of her crew, [Footnote: Midshipman Lee, in his letter already quoted, says "not five men were left unhurt"; this would of course include bruises, etc., as hurts.] most of her guns on the engaged side were dismounted, and her stout masts had been splintered till they looked like bundles of matches; her sails had been torn to rags, and she was forced to strike, about two hours after she had fired the first broadside. Without pausing a minute the Saratoga again hauled on her starboard hawser till her broadside was sprung to bear on the Linnet, and the ship and brig began a brisk fight, which the Eagle from her position could take no part in, while the Ticonderoga was just finishing up the British galleys. The shattered and disabled state of the Linnet's masts, sails, and yards precluded the most distant hope of Capt. Pring's effecting his escape by cutting his cable; but he kept up a most gallant fight with his greatly superior foe, in hopes that some of the gun-boats would come and tow him off, and despatched a lieutenant to the Confiance to ascertain her state. The lieutenant returned with news of Capt. Downie's death, while the British gun-boats had been driven half a mile off; and, after having maintained the fight single-handed for fifteen minutes, until, from the number of shot between wind and water, the water had risen a foot above her lower deck, the plucky little brig hauled down her colors, and the fight ended, a little over two hours and a half after the first gun had been fired. Not one of the larger vessels had a mast that would bear canvas, and the prizes were in a sinking condition. The British galleys drifted to leeward, none with their colors up; but as the Saratoga's boarding-officer passed along the deck of the Confiance he accidentally ran against a lock-string of one of her starboard guns, [Footnote: A sufficient commentary, by the way, on James' assertion that the guns of the Confiance had to be fired by matches, as the gun-locks did not fit!] and it went off. This was apparently understood as a signal by the galleys, and they moved slowly off, pulling but a very few sweeps, and not one of them hoisting an ensign.