полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

Wasp, Ship Newburyport $77,459.60 160 22 509 Built Frolic, " Boston 72,094.82 " " " " Peacock, " New York 75,644.36 " " " " Ontario, " Baltimore 59,343.69 " " " " Erie, " " 56,174.36 " " " " Tom Bowline, Schooner Portsmouth 13,000.00 90 12 260 Purchased Lynx, " Washington 50 6 Built Epervier, Brig England 50,000.00 130 18 477 Captured Flambeau, " Baltimore 14,000.00 90 14 300 Purchased -+– Spark, " " 17,389.00 " " " " | Firefly, " " 17,435.00 " " 333 " | Torch, Schooner " 13,000.00 60 12 260 " | Spitfire, " " 20,000.00 " " 286 " '– Eagle, " N.O. " " 270 " -+– Prometheus, " Philadelphia 20,000.00 " " 290 " | Chippeway, Brig R.I. 52,000.00 90 14 390 " | Saranac, " Middleton 26,000.00 " " 360 " '– Boxer, " " 26,000.00 " " 370 " Despatch, Schooner 23 2 52

The first 5 small vessels that are bracketed were to cruise under Commodore Porter; the next 4 under Commodore Perry; but the news of peace arrived before either squadron put to sea. Some of the vessels under this catalogue were really almost ready for sea at the end of 1813; and some that I have included in the catalogue of 1815 were almost completely fitted at the end of 1814,—but this arrangement is practically the best.

LIST OF VESSELS LOST TO THE BRITISH.

1. Destroyed by British Armies.

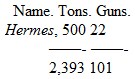

Name. Tons. Guns. Columbia, 1,508 52-+– Destroyed to prevent them Adams, 760 28 | falling into hands of enemy. Argus. 509 22 '– Carolina. 230 14 Destroyed by battery. – – 3,007 116

2. Captured, Etc., By British Navy on Ocean.

Name. Tons. Guns. Essex. 860 46 Captured by frigate and corvette. Frolic. 509 22 " by frigate and schooner. Rattlesnake, 258 16 " by frigate. Syren, 250 16 " by seventy-four. – – 1,877 100

Total, 4,884 tons. 216 guns

There were also a good many gun-boats, which I do not count, because, as already said, they were often not as large as the barges that were sunk and taken in attacking them, as at Craney Island, etc.

LIST OF VESSELS TAKEN FROM THE BRITISH.

1. Captured by American Privateers.

Name. Tons. Guns. Ballabou, 86 4 Landrail, 76 4

2. Captured, Etc., By British Navy on Ocean.

Name. Tons. Guns. Epervier, 477 18 captured by sloop Peacock. Avon, 477 20 sunk " " Wasp. Reindeer, 477 19 " " " ". Pictou, 300 14 captured by frigate.

3. Sunk in Attacking Fort.

Taking into account the losses on the lakes, there was not very much difference in the amount of damage done to each combatant by the other; but both as regards the material results and the moral effects, the balance inclined largely to the Americans. The chief damage done to our navy was by the British land-forces, and consisted mainly in forcing us to burn an unfinished frigate and sloop. On the ocean our three sloops were captured in each case by an overwhelming force, against which no resistance could be made, and the same was true of the captured British schooner. The Essex certainly gained as much honor as her opponents. There were but three single ship actions, in all of which the Americans were so superior in force as to give them a very great advantage; nevertheless, in two of them the victory was won with such perfect impunity and the difference in the loss and damage inflicted was so very great, that I doubt if the result would have been affected if the odds had been reversed. In the other case, that of the Reindeer, the defeated party fought at a still greater disadvantage, and yet came out of the conflict with full as much honor as the victor. No man with a particle of generosity in his nature can help feeling the most honest admiration for the unflinching courage and cool skill displayed by Capt. Manners and his crew. It is worthy of notice (remembering the sneers of so many of the British authors at the "wary circumspection" of the Americans) that Capt. Manners, who has left a more honorable name than any other British commander of the war, excepting Capt. Broke, behaved with the greatest caution as long as it would serve his purpose, while he showed the most splendid personal courage afterward. It is this combination of courage and skill that made him so dangerous an antagonist; it showed that the traditional British bravery was not impaired by refusing to adhere to the traditional British tactics of rushing into a fight "bull-headed." Needless exposure to danger denotes not so much pluck as stupidity. Capt. Manners had no intention of giving his adversary any advantage he could prevent. No one can help feeling regret that he was killed; but if he was to fall, what more glorious death could he meet? It must be remembered that while paying all homage to Capt. Manners, Capt. Blakely did equally well. It was a case where the victory between two combatants, equal in courage and skill, was decided by superior weight of metal and number of men.

PRIZES MADE.

Name of ship. Number of prizes. President 3 Constitution 6 Adams 10 Frolic 2 Wasp 15 Peacock 15 Hornet 1 Small craft 35 – 87

Chapter VIII

1814ON THE LAKESONTARIO-The contest one of ship-building merely—Extreme caution of the commanders, verging on timidity—Yeo takes Oswego, and blockades Sackett's Harbor—British gun-boats captured—Chauncy blockades Kingston—ERIE—Captain Sinclair's unsuccessful expedition—Daring and successful cutting-out expeditions of the British—CHAMPLAIN—Macdonough's victory.

Ontario.

The winter was spent by both parties in preparing more formidable fleets for the ensuing summer. All the American schooners had proved themselves so unfit for service that they were converted into transports, except the Sylph, which was brig-rigged and armed like the Oneida. Sackett's Harbor possessed but slight fortifications, and the Americans were kept constantly on the alert, through fear lest the British should cross over. Commodore Chauncy and Mr. Eckford were as unremitting in their exertions as ever. In February two 22-gun brigs, the Jefferson and Jones, and one large frigate of 50 guns, the Superior, were laid; afterward a deserter brought in news of the enormous size of one of the new British frigates, and the Superior was enlarged to permit her carrying 62 guns. The Jefferson was launched on April 7th, the Jones on the 10th; and the Superior on May 2d,—an attempt on the part of the British to blow her up having been foiled a few days before. Another frigate, the Mohawk, 42, was at once begun. Neither guns nor men for the first three ships had as yet arrived, but they soon began to come in, as the roads got better and the streams opened. Chauncy and Eckford, besides building ships that were literally laid down in the forest, and seeing that they were armed with heavy guns, which, as well as all their stores, had to be carried overland hundreds of miles through the wilderness, were obliged to settle quarrels that occurred among the men, the most serious being one that arose from a sentinel's accidentally killing a shipwright, whose companions instantly struck work in a body. What was more serious, they had to contend with such constant and virulent sickness that it almost assumed the proportions of a plague. During the winter it was seldom that two thirds of the force were fit for duty, and nearly a sixth of the whole number of men in the port died before navigation opened. [Footnote: Cooper mentions that in five months the Madison buried a fifth of her crew.]

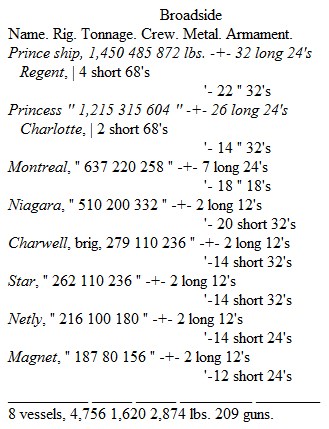

Meanwhile Yeo had been nearly as active at Kingston, laying down two frigates and a huge line-of-battle ship, but his shipwrights did not succeed in getting the latter ready much before navigation closed. The Prince Regent, 58, and Princess Charlotte, 42, were launched on April 15th. I shall anticipate somewhat by giving tabular lists of the comparative forces, after the two British frigates, the two American frigates, and the two American brigs had all been equipped and manned. Commodore Yeo's original six cruisers had been all renamed, some of them re-armed, and both the schooners changed into brigs. The Wolfe, Royal George, Melville, Moira, Beresford, and Sydney Smith, were now named respectively Montreal, Niagara, Star, Charwell, Netly, and Magnet. On the American side there had been but slight changes, beyond the alteration of the Sylph into a brig armed like the Oneida. Of the Superior's 62 guns, 4 were very shortly sent on shore again.

CHAUNCY'S SQUADRON.

This is considerably less than James makes it, as he includes all the schooners, which were abandoned as cruisers, and only used as transports or gun-boats. Similarly Sir James had a large number of gun-boats, which are not included in his cruising force. James thus makes Chauncy's force 2,321 men, and a broadside of 4,188 lbs.

YEO'S SQUADRON

This tallies pretty well with James' statement, which (on p. 488) is 1,517 men, and a broadside of 2,752 lbs. But there are very probably errors as regards the armaments of the small brigs, which were continually changed. At any rate the American fleet was certainly the stronger, about in the proportion of six to five. The disproportion was enough to justify Sir James in his determination not to hazard a battle, although the odds were certainly not such as British commanders had been previously accustomed to pay much regard to. Chauncy would have acted exactly as his opponent did, had he been similarly placed. The odds against the British commodore were too great to be overcome, where the combatants were otherwise on a par, although the refusal to do battle against them would certainly preclude Yeo from advancing any claims to superiority in skill or courage. The Princess Charlotte and Niagara were just about equal to the Mohawk and Madison, and so were the Charwell and Netly to the Oneida and Sylph; but both the Star and Magnet together could hardly have matched either the Jones or the Jefferson, while the main-deck 32's of the Superior gave her a great advantage over the Prince Regent's 24's, where the crews were so equal; and the Pike was certainly too heavy for the Montreal. A decided superiority in the effectiveness of both crews and captains could alone have warranted Sir James Lucas Yeo in engaging, and this superiority he certainly did not possess.

This year the British architects outstripped ours in the race for supremacy, and Commodore Yeo put out of port with his eight vessels long before the Americans were ready. His first attempt was a successful attack on Oswego. This town is situated some 60 miles distant from Sackett's Harbor, and is the first port on the lake which the stores, sent from the seaboard to Chauncy, reached. Accordingly it was a place of some little importance, but was very much neglected by the American authorities. It was insufficiently garrisoned, and was defended only by an entirely ruined fort of 6 guns, two of them dismounted. Commodore Yeo sailed from Kingston to attack it on the 3d of May, having on board his ships a detachment of 1,080 troops. Oswego was garrisoned by less than 300 men, [Footnote: General order of Gen. Jacob Brown, by R. Jones, Ass. Adj.-General, May 12, 1814.] chiefly belonging to a light artillery regiment, with a score or two of militia; they were under the command of Colonel Mitchell. The recaptured schooner Growler was in port, with 7 guns destined for the Harbor; she was sunk by her commander, but afterward raised and carried off by the foe.

On the 5th Yeo appeared off Oswego and sent in Captain Collier and 13 gun-boats to draw the fort's fire; after some firing between them and the four guns mounted in the fort (two long 24's, one long 12, and one long 6), the gun-boats retired. The next day the attack was seriously made. The Princess Charlotte, Montreal, and Niagara engaged the batteries, while the Charwell and Star scoured the woods with grape to clear them of the militia. [Footnote: Letter of General Gordon Drummond, May 7, 1814.] The debarkation of the troops was superintended by Captain O'Connor, and until it was accomplished the Montreal sustained almost the whole fire of the fort, being set on fire three times, and much cut up in hull, masts, and rigging. [Footnote: Letter of Sir James Lucas Yeo, May 17, 1814.] Under this fire 800 British troops were landed, under Lieutenant-Colonel Fischer, assisted by 200 seamen, armed with long pikes, under Captain Mulcaster. They moved gallantly up the hill, under a heavy fire, and carried the fort by assault; Mitchell then fell back unmolested to the Falls, about 12 miles above the town, where there was a large quantity of stores. But he was not again attacked. The Americans lost 6 men killed, including Lieutenant Blaeny, 38 wounded, and 25 missing, both of these last falling into the enemy's hands. The British lost 22 soldiers, marines, and seamen (including Captain Hollaway) killed, and 73 (including the gallant Captain Mulcaster dangerously, and Captain Popham slightly) wounded, [Footnote: Letter of Lieut.-Col. V. Fischer, May 17, 1814. James says "18 killed and 64 wounded," why I do not know; the official report of Col. Fischer, as quoted, says: "Of the army, 19 killed and 62 wounded; of the navy, 3 killed and 11 wounded."] the total loss being 95—nearly a third of the American force engaged. General Drummond, in his official letter, reports that "the fort being everywhere almost open, the whole of the garrison * * * effected their escape, except about 60 men, half of them wounded." No doubt the fort's being "everywhere almost open" afforded excellent opportunities for retreat; but it was not much of a recommendation of it as a structure intended for defence.

The British destroyed the four guns in the battery, and raised the Growler and carried her off, with her valuable cargo of seven long guns. They also carried off a small quantity of ordnance stores and some flour, and burned the barracks; otherwise but little damage was done, and the Americans reoccupied the place at once. It certainly showed great lack of energy on Commodore Yeo's part that he did not strike a really important blow by sending an expedition up to destroy the quantity of stores and ordnance collected at the Falls. But the attack itself was admirably managed. The ships were well placed, and kept up so heavy a fire on the fort as to effectually cover the debarkation of the troops, which was very cleverly accomplished; and the soldiers and seamen behaved with great gallantry and steadiness, their officers leading them, sword in hand, up a long, steep hill, under a destructive fire. It was similar to Chauncy's attacks on York and Fort George, except that in this case the assailants suffered a much severer loss compared to that inflicted on the assailed. Colonel Mitchell managed the defence with skill, doing all he could with his insufficient materials.

After returning to Kingston, Yeo sailed with his squadron for Sackett's Harbor, where he appeared on May 19th and began a strict blockade. This was especially troublesome because most of the guns and cables for the two frigates had not yet arrived, and though the lighter pieces and stores could be carried over land, the heavier ones could only go by water, which route was now made dangerous by the presence of the blockading squadron. The very important duty of convoying these great guns was entrusted to Captain Woolsey, an officer of tried merit. He decided to take them by water to Stony Creek, whence they might be carried by land to the Harbor, which was but three miles distant; and on the success of his enterprise depended Chauncy's chances of regaining command of the lake. On the 28th of May, at sunset, Woolsey left Oswego with 19 boats, carrying 21 long 32's, 10 long 24's, three 42-pound carronades, and 10 cables—one of the latter, for the Superior, being a huge rope 22 inches in circumference and weighing 9,600 pounds. The boats rowed all through the night, and at sunrise on the 29th 18 of them found themselves off the Big Salmon River, and, as it was unsafe to travel by daylight, Woolsey ran up into Big Sandy Creek, 8 miles from the Harbor. The other boat, containing two long 24's and a cable, got out of line, ran into the British squadron, and was captured. The news she brought induced Sir James Yeo at once to send out an expedition to capture the others. He accordingly despatched Captains Popham and Spilsbury in two gun-boats, one armed with one 68-pound and one 24-pound carronade, and the other with a long 32, accompanied by three cutters and a gig, mounting between them two long 12's and two brass 6's, with a total of 180 men. [Footnote: James, vi. 487; while Cooper says 186, James says the British loss was 18 killed and 50 wounded; Major Appling says "14 were killed, 28 wounded, and 27 marines and 106 sailors captured."] They rowed up to Sandy Creek and lay off its mouth all the night, and began ascending it shortly after daylight on the 30th. Their force, however, was absurdly inadequate for the accomplishment of their object. Captain Woolsey had been reinforced by some Oneida Indians, a company of light artillery, and some militia, so that his only care was, not to repulse, but to capture the British party entire, and even this did not need any exertion. He accordingly despatched Major Appling down the river with 120 riflemen [Footnote: Letter from Major D. Appling, May 30, 1814.] and some Indians to lie in ambush. [Footnote: Letter of Capt. M. T. Woolsey, June 1, 1814. There were about 60 Indians: In all, the American force amounted to 180 men. James adds 30 riflemen, 140 Indians, and "a large body of militia and cavalry,"—none of whom were present.] When going up the creek the British marines, under Lieutenant Cox, were landed on the left bank, and the small-arm men, under Lieutenant Brown, on the right bank; while the two captains rowed up the stream between them, throwing grape into the bushes to disperse the Indians. Major Appling waited until the British were close up, when his riflemen opened with so destructive a volley as to completely demoralize and "stampede" them, and their whole force was captured with hardly any resistance, the American having only one man slightly wounded. The British loss was severe,—18 killed and 50 dangerously wounded, according to Captain Popham's report, as quoted by James; or "14 killed and 28 wounded," according to Major Appling's letter. It was a very clever and successful ambush.

On June 6th Yeo raised the blockade of the Harbor, but Chauncy's squadron was not in condition to put out till six weeks later, during which time nothing was done by either fleet, except that two very gallant cutting-out expeditions were successfully attempted by Lieutenant Francis H. Gregory, U.S.N. On June 16th he left the Harbor, accompanied by Sailing-masters Vaughan and Dixon and 22 seamen, in three gigs, to intercept some of the enemy's provision schooners; on the 19th he was discovered by the British gun-boat Black Snake, of one 18-pound carronade and 18 men, commanded by Captain H. Landon. Lieutenant Gregory dashed at the gun-boat and carried it without the loss of a man; he was afterward obliged to burn it, but he brought the prisoners, chiefly royal marines, safely into port. On the 1st of July he again started out, with Messrs. Vaughan and Dixon, and two gigs. The plucky little party suffered greatly from hunger, but on the 5th he made a sudden descent on Presque Isle, and burned a 14-gun schooner just ready for launching; he was off before the foe could assemble, and reached the Harbor in safety next day.

On July 31st Commodore Chauncy sailed with his fleet; some days previously the larger British vessels had retired to Kingston, where a 100-gun two-decker was building. Chauncy sailed up to the head of the lake, where he intercepted the small brig Magnet. The Sylph was sent in to destroy her, but her crew ran her ashore and burned her. The Jefferson, Sylph, and Oneida were left to watch some other small craft in the Niagara; the Jones was kept cruising between the Harbor and Oswego, and with the four larger vessels Chauncy blockaded Yeo's four large vessels lying in Kingston. The four American vessels were in the aggregate of 4,398 tons, manned by rather more than 1,350 men, and presenting in broadside 77 guns, throwing 2,328 lbs. of shot. The four British vessels measured in all about 3,812 tons, manned by 1,220 men, and presenting in broadside 74 guns, throwing 2,066 lbs. of shot. The former were thus superior by about 15 per cent., and Sir James Yeo very properly declined to fight with the odds against him—although it was a nicer calculation than British commanders had been accustomed to enter into.

Major-General Brown had written to Commodore Chauncy on July 13th: "I do not doubt my ability to meet the enemy in the field and to march in any direction over his country, your fleet carrying for me the necessary supplies. We can threaten Forts George and Niagara, and carry Burlington Heights and York, and proceed direct to Kingston and carry that place. For God's sake let me see you: Sir James will not fight." To which Chauncy replied: "I shall afford every assistance in my power to cooperate with the army whenever it can be done without losing sight of the great object for the attainment of which this fleet has been created,—the capture or destruction of the enemy's fleet. But that I consider the primary object. * * * We are intended to seek and fight the enemy's fleet, and I shall not be diverted from my efforts to effectuate it by any sinister attempt to render us subordinate to, or an appendage of, the army." That is, by any "sinister attempt" to make him cooperate intelligently in a really well-concerted scheme of invasion. In further support of these noble and independent sentiments, he writes to the Secretary of the Navy on August 10th [Footnote: See Niles, vii, 12, and other places (under "Chauncy" in index).], "I told (General Brown) that I should not visit the head of the lake unless the enemy's fleet did so. * * * To deprive the enemy of an apology for not meeting me, I have sent ashore four guns from the Superior to reduce her armament in number to an equality with the Prince Regent's, yielding the advantage of their 68-pounders. The Mohawk mounts two guns less than the Princess Charlotte, and the Montreal and Niagara are equal to the Pike and Madison." He here justifies his refusal to co-operate with General Brown by saying that he was of only equal force with Sir James, and that he has deprived the latter of "an apology" for not meeting him. This last was not at all true. The Mohawk and Madison were just about equal to the Princess Charlotte and Niagara: but the Pike was half as strong again as the Montreal; and Chauncy could very well afford to "yield the advantage of their 68-pounders," when in return Sir James had to yield the advantage of Chauncy's long 32's and 42-pound carronades. The Superior was a 32-pounder frigate, and, even without her four extra guns, was about a fourth heavier than the Prince Regent with her 24-pounders. Sir James was not acting more warily than Chauncy had acted during June and July, 1813. Then he had a fleet which tonned 1,701, was manned by 680 men, and threw at a broadside 1,099 lbs. of shot; and he declined to go out of port or in any way try to check the operation of Yeo's fleet which tonned 2,091, was manned by 770 men, and threw at a broadside 1,374 lbs. of shot. Chauncy then acted perfectly proper, no doubt, but he could not afford to sneer at Yeo for behaving in the same way. Whatever either commander might write, in reality he well knew that his officers and crews were, man for man, just about on a par with those of his antagonists, and so, after the first brush or two, he was exceedingly careful to see that the odds were not against him. Chauncy, in his petulant answers to Brown's letter, ignored the fact that his superiority of force would prevent his opponent from giving battle, and would, therefore, prevent any thing more important than a blockade occurring.