полная версия

полная версияScientific American Supplement, No. 275, April 9, 1881

In the fall of 1871 I entered into a contract with Mr. C. A. Pillsbury, owner of the Taylor Mill and senior partner in the firm by whom the Minneapolis Mill was operated, to put both those mills into condition to make the same grade of flour as Mr. Christian was making. The consideration in the contract was 5,000 dols. At the above mills I met to some extent the same obstruction in regard to millers striking as had greeted me at Mr. Christian's mill earlier in the year; but among those who did not strike at the Minneapolis Mill I saw, for the first time, Mr. Stephens–then still in his apprenticeship–whom Mr. Hoppin declares to have been, "so far as I know," the first miller to use smooth stones. If Mr. Hoppin is right in his assertion, perhaps he will explain why, during the eight months I was at the Washburn Mill, Mr. Stephens did not make a corresponding improvement in the product of the Minneapolis Mill. That he did not do this is amply proved by the fact of Mr. Pillsbury giving me 5,000 dols. to introduce improvements into his mills, when, supposing Mr. Hoppin's statement to be correct, he might have had the same alterations carried out under Mr. Stephens' direction at a mere nominal cost. As a matter of fact, the stones in both the Taylor and Minneapolis Mills were as rough as any in the Washburn Mill when I took charge of them.

Thus it appears (1) that the flour made by the mill in which Stephens was employed was not improved in quality, while that of the Washburn Mill, where he was not employed, became the finest that had ever been made in the United States at that time. That (2) the owner of the mill in which Mr. Stephens was employed, as he was not making good flour, engaged me at a large cost to introduce into his mills the alterations by which only, both Mr. Hoppin and myself agree, could any material improvement in the milling of that period be effected, .viz., smooth, true, and well-balanced stones.–GEO. T. SMITH.

For breachy animals do not use barbed fences. To see the lacerations that these fences have produced upon the innocent animals should be sufficient testimony against them. Many use pokes and blinders on cattle and goats, but as a rule such things fail. The better way is to separate breachy animals from the lot, as others will imitate their habits sooner or later, and then, if not curable, sell them.

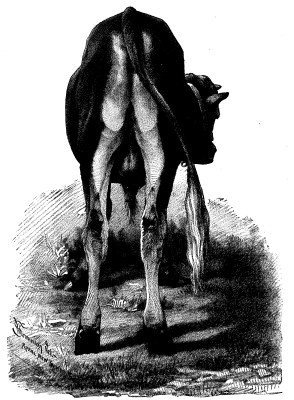

THE GUENON MILK-MIRROR

The name of the simple Bordeaux peasant is, and should be, permanently associated with his discovery that the milking qualities of cows were, to a considerable extent, indicated by certain external marks easily observed. We had long known that capacious udders and large milk veins, combined with good digestive capacity and a general preponderance of the alimentary over the locomotive system, were indications that rarely misled in regard to the ability of a cow to give much milk; but to judge of the amount of milk a cow would yield, and the length of time she would hold out in her flow, two or three years before she could be called a cow–this was Guenon's great accomplishment, and the one for which he was awarded a gold medal by the Agricultural Society of his native district. This was the first of many honors with which he was rewarded, and it is much to say that no committee of agriculturists who have ever investigated the merits of the system have ever spoken disparagingly of it. Those who most closely study it, especially following Guenon's original system, which has never been essentially improved upon, are most positive in regard to its truth, enthusiastic in regard to its value.

The fine, soft hair upon the hinder part of a cow's udder for the most part turns upward. This upward-growing hair extends in most cases all over that part of the udder visible between the hind legs, but is occasionally marked by spots or mere lines, usually slender ovals, in which the hair grows down. This tendency of the hair to grow upward is not confined to the udder proper; but extends out upon the thighs and upward to the tail. The edges of this space over which the hair turns up are usually distinctly marked, and, as a rule, the larger the area of this space, which is called the "mirror" or "escutcheon," the more milk the cow will give, and the longer she will continue in milk.

ESCUTCHEON OF THE JERSEY BULL-CALF, GRAND MIRROR, 4,904.

That portion of the escutcheon which covers the udder and extends out on the inside of each thigh, has been designated as the udder or mammary mirror; that which runs upward towards the setting on of the tail, the rising or placental mirror. The mammary mirror is of the greater value, yet the rising mirror is not to be disregarded. It is regarded of especial moment that the mirror, taken as a whole, be symmetrical, and especially that the mammary mirror be so; yet it often occurs that it is far otherwise, its outline being often very fantastical–exhibiting deep bays, so to speak, and islands of downward growing hair. There are also certain "ovals," never very large, yet distinct, which do not detract from the estimated value of an escutcheon; notably those occurring on the lobes of the udder just above the hind teats. These are supposed to be points of value, though for what reason it would be hard to tell, yet they do occur upon some of the very best milch cows, and those whose mirrors correspond most closely to their performances.

Mr. Guenon's discovery enables breeders to determine which of their calves are most promising, and in purchasing young stock it affords indications which rarely fail as to their comparative milk yield. These indications occasionally prove utterly fallacious, and Mr. Guenon gives rules for determining this class, which he calls "bastards," without waiting for them to fail in their milk. The signs are, however, rarely so distinct that one would be willing to sell a twenty-quart cow, whose yield confirmed the prediction of her mirror at first calving, because of the possibility of the going dry in two months, or so, as indicated by her bastardy marks.

It is an interesting fact that the mirrors of bulls (which are much like those of cows, but less extensive in every direction) are reflected in their daughters. This gives rise to the dangerous custom of breeding for mirrors, rather than for milk. What the results may be after a few years it is easy to see. The mirror, being valued for its own sake–that is, because it sells the heifers–will be likely to lose its practical significance and value as a milk mirror.

We have a striking photograph of a young Jersey bull, the property of Mr. John L. Hopkins, of Atlanta, Ga., and called "Grand Mirror." This we have caused to be engraved and the mirror is clearly shown. A larger mirror is rarely seen upon a bull. We hope in a future number to exhibit some cows' mirrors of different forms and degrees of excellence.–Rural New Yorker.

TWO GOOD LAWN TREES

The negundo, or ash-leaved maple, as it is called in the Eastern States, better known at the West as a box elder, is a tree that is not known as extensively as it deserves. It is a hard maple, that grows as rapidly as the soft maple; is hardy, possesses a beautiful foliage of black green leaves, and is symmetrical in shape. Through eastern Iowa I found it growing wild, and a favorite tree with the early settlers, who wanted something that gave shade and protection to their homes quickly on their prairie farms. Brought east, its growth is rapid, and it loses none of the characteristics it possessed in its western home. Those who have planted it are well pleased with it. It is a tree that transplants easily, and I know of no reason why it should not be more popular.

For ornamental lawn planting, I give pre-eminence to the cut-leaf weeping birch. Possessing all the good qualities of the white birch, it combines with them a beauty and delicate grace yielded by no other tree. It is an upright grower, with slender, drooping branches, adorned with leaves of deep rich green, each leaf being delicately cut, as with a knife, into semi-skeletons. It holds its foliage and color till quite late in the fall. The bark, with age, becomes white, resembling the white birch, and the beauty of the tree increases with its age. It is a free grower, and requires no trimming. Nature has given it a symmetry which art cannot improve.

H.T.J.

CUTTING SODS FOR LAWNS

I am a very good sod layer, and used to lay very large lawns–half to three-quarters of an acre. I cut the sods as follows: Take a board eight to nine inches wide, four, five, or six feet long, and cut downward all around the board, then turn the board over and cut again alongside the edge of the board, and so on as many sods as needed. Then cut the turf with a sharp spade, all the same lengths. Begin on one end, and roll together. Eight inches by five feet is about as much as a man can handle conveniently. It is very easy to load them on a wagon, cart, or barrow, and they can be quickly laid. After laying a good piece, sprinkle a little with a watering pot, if the sods are dry; then use the back of the spade to smooth them a little. If a very fine effect is wanted, throw a shovelful or two of good earth over each square yard, and smooth it with the back of a steel rake.

F.H.

[COUNTRY GENTLEMAN.]

HORTICULTURAL NOTES

The Western New York Society met at Rochester, January 26.

New Apples, Pears, Grapes, etc.--Wm. C Barry, secretary of the committee on native fruits, read a full report. Among the older varieties of the apple, he strongly recommended Button Beauty, which had proved so excellent in Massachusetts, and which had been equally successful at the Mount Hope Nurseries at Rochester; the fine growth of the tree and its great productiveness being strongly in its favor. The Wagener and Northern Spy are among the finer sorts. The Melon is one of the best among the older sorts; the fruit being quite tender will not bear long shipment, but it possesses great value for home use, and being a poor grower, it had been thrown aside by nurserymen and orchardists. It should be top-grafted on more vigorous sorts. The Jonathan is another fine sort of slender growth, which should be top-grafted.

Among new pears, Hoosic and Frederic Clapp were highly commended for their excellence. Some of the older peaches of fine quality had of late been neglected, and among them Druid Hill and Brevoort.

Among the many new peaches highly recommended for their early ripening, there was great resemblance to each other, and some had proved earlier than Alexander.

Of the new grapes, Lady Washington was the most promising. The Secretary was a failure. The Jefferson was a fine sort, of high promise.

Among the new white grapes, Niagara, Prentiss, and Duchess stood pre-eminent, and were worthy of the attention of cultivators. The Vergennes, from Vermont, a light amber colored sort, was also highly commended. The Elvira, so highly valued in Missouri, does not succeed well here. Several facts were stated in relation to the Delaware grape, showing its reliability and excellence.

Several new varieties of the raspberry were named, but few of them were found equal to the best old sorts. If Brinckle's Orange were taken as a standard for quality, it would show that none had proved its equal in fine quality. The Caroline was like it in color, but inferior in flavor. The New Rochelle was of second quality. Turner was a good berry, but too soft for distant carriage.

Of the many new strawberries named, each seemed to have some special drawback. The Bidwell, however, was a new sort of particular excellence, and Charles Downing thinks it the most promising of the new berries.

Discussion on Grapes.--C. W. Beadle, of Ontario, in allusion to Moore's Early grape, finds it much earlier than the Concord, and equal to it in quality, ripening even before the Hartford. S. D. Willard, of Geneva, thought it inferior to the Concord, and not nearly so good as the Worden. The last named was both earlier and better than the Concord, and sold for seven cents per pound when the Concord brought only four cents. C. A. Green, of Monroe County, said the Lady Washington proved to be a very fine grape, slightly later than Concord. P. L. Perry, of Canandaigua, said that the Vergennes ripens with Hartford, and possesses remarkable keeping qualities, and is of excellent quality and free from pulp. He presented specimens which had been kept in good condition. He added, in relation to the Worden grape, that some years ago it brought 18 cents per pound in New York when the Concord sold three days later for only 8 cents. [In such comparisons, however, it should be borne in mind that new varieties usually receive more attention and better culture, giving them an additional advantage.]

The Niagara grape received special attention from members. A. C. Younglove, of Yates County, thought it superior to any other white grape for its many good qualities. It was a vigorous and healthy grower, and the clusters were full and handsome. W. J. Fowler, of Monroe County, saw the vine in October, with the leaves still hanging well, a great bearer and the grape of fine quality. C. L. Hoag, of Lockport, said he began to pick the Niagara on the 26th of August, but its quality improved by hanging on the vine. J. Harris, of Niagara County, was well acquainted with the Niagara, and indorsed all the commendation which had been uttered in its favor. T. C. Maxwell said there was one fault–we could not get it, as it was not in market. W. C. Barry, of Rochester, spoke highly of the Niagara, and its slight foxiness would be no objection to those who like that peculiarity. C. L. Hoag thought this was the same quality that Col. Wilder described as "a little aromatic." A. C. Younglove found the Niagara to ripen with the Delaware. Inquiry being made relative to the Pockington grape, H. E. Hooker said it ripened as early as the Concord. C. A. Green was surprised that it had not attracted more attention, as he regarded it as a very promising grape. J. Charlton, of Rochester, said that the fruit had been cut for market on the 29th of August, and on the 6th of September it was fully ripe; but he has known it to hang as late as November. J. S. Stone had found that when it hung as late as November it became sweet and very rich in flavor.

New Peaches.--A. C. Younglove had found such very early sorts as Alexander and Amsden excellent for home use, but not profitable for market. The insects and birds made heavy depredations on them. While nearly all very early and high-colored sorts suffer largely from the birds, the Rivers, a white peach, does not attract them, and hence it may be profitable for market if skillfully packed; rough and careless handling will spoil the fruit. He added that the Wheatland peach sustains its high reputation, and he thought it the best of all sorts for market, ripening with Late Crawford. It is a great bearer, but carries a crop of remarkably uniform size, so that it is not often necessary to throw out a bad specimen. This is the result of experience with it by Mr. Rogers at Wheatland, in Monroe County, and at his own residence in Vine Valley. S. D. Willard confirmed all that Mr. Younglove had said of the excellence of the Rivers peach. He had ripened the Amsden for several years, and found it about two weeks earlier than the Rivers, and he thought if the Amsden were properly thinned, it would prevent the common trouble of its rotting; such had been his experience. E. A. Bronson, of Geneva, objected to making very early peaches prominent for marketing, as purchasers would prefer waiting a few days to paying high prices for the earliest, and he would caution people against planting the Amsden too largely, and its free recommendation might mislead. May's Choice was named by H. E. Hooker as a beautiful yellow peach, having no superior in quality, but perhaps it may not be found to have more general value than Early and Late Crawford. It is scarcely distinguishable in appearance from fine specimens of Early Crawford. W. C. Barry was called on for the most recent experience with the Waterloo, but said he was not at home when it ripened, but he learned that it had sustained its reputation. A. C. Younglove said that the Salway is the best late peach, ripening eight or ten days after the Smock. S. D. Willard mentioned an orchard near Geneva, consisting of 25 Salway trees, which for four years had ripened their crop and had sold for $4 per bushel in the Philadelphia market, or for $3 at Geneva–a higher price than for any other sort–and the owner intends to plant 200 more trees. W. C. Barry said the Salway will not ripen at Rochester. Hill's Chili was named by some members as a good peach for canning and drying, some stating that it ripens before and others after Late Crawford. It requires thinning on the tree, or the fruit will be poor. The Allen was pronounced by Mr. Younglove as an excellent, intensely high-colored late peach.

Insects Affecting Horticulture.–Mr. Zimmerman spoke of the importance of all cultivators knowing so much of insects and their habits as to distinguish their friends from their enemies. When unchecked they increase in an immense ratio, and he mentioned as an instance that the green fly (Aphis) in five generations may become the parent of six thousand million descendants. It is necessary, then, to know what other insects are employed in holding them in check, by feeding on them. Some of our most formidable insects have been accidentally imported from Europe, such as the codling moth, asparagus beetle, cabbage butterfly, currant worm and borer, elm-tree beetle, hessian fly, etc.; but in nearly every instance these have come over without bringing their insect enemies with them, and in consequence they have spread more extensively here than in Europe. It was therefore urged that the Agricultural Department at Washington be requested to import, as far as practicable, such parasites as are positively known to prey on noxious insects. The cabbage fly eluded our keen custom-house officials in 1866, and has enjoyed free citizenship ever since. By accident, one of its insect enemies (a small black fly) was brought over with it, and is now doing excellent work by keeping the cabbage fly in check.

The codling moth, one of the most formidable fruit destroyers, may be reduced in number by the well-known paper bands; but a more efficient remedy is to shower them early in the season with Paris green, mixed in water at the rate of only one pound to one hundred gallons of water, with a forcing pump, soon after blossoming. After all the experiments made and repellents used for the plum curculio, the jarring method is found the most efficient and reliable, if properly performed. Various remedies for insects sometimes have the credit of doing the work, if used in those seasons when the insects happen to be few. With some insects, the use of oil is advantageous, as it always closes up their breathing holes and suffocates them. The oil should be mixed with milk, and then diluted as required, as the oil alone cannot be mixed with the water. As a general remedy, Paris green is the strongest that can be applied. A teaspoonful to a tablespoonful, in a barrel of water, is enough. Hot water is the best remedy for house plants. Place one hand over the soil, invert the pot, and plunge the foliage for a second only at a time in water heated to from 150° to 200°F, according to the plants; or apply with a fine rose. The yeast remedy has not proved successful in all cases.

Among beneficial insects, there are about one hundred species of lady bugs, and, so far as known, all are beneficial. Cultivators should know them. They destroy vast quantities of plant lice. The ground beetles are mostly cannibals, and should not be destroyed. The large black beetle, with coppery dots, makes short work with the Colorado potato beetles; and a bright green beetle will climb trees to get a meal of canker worms. Ichneumon flies are among our most useful insects. The much-abused dragon flies are perfectly harmless to us, but destroy many mosquitoes and flies.

Among insects that attack large fruits is the codling moth, to be destroyed by paper bands, or with Paris green showered in water. The round-headed apple-tree borer is to be cut out, and the eggs excluded with a sheet of tarred paper around the stem, and slightly sunk in the earth. For the oyster-shell bark louse, apply linseed oil. Paris green, in water, will kill the canker worm. Tobacco water does the work for plant lice. Peach-tree borers are excluded with tarred or felt paper, and cut out with a knife. Jar the grape flea beetle on an inverted umbrella early in the morning. Among small-fruit insects, the strawberry worms are readily destroyed with hellebore, an ounce to a gallon of warm water. The same remedy destroys the imported currant worm.

Insect Destroyers.–Prof. W. Saunders, of the Province of Ontario, followed Mr. Zimmerman with a paper on other departments of the same general subject, which contained much information and many suggestions of great value to cultivators. He had found Paris green an efficient remedy for the bud-moth on pear and other trees. He also recommends Paris green for the grapevine flea beetle. Hellebore is much better for the pear slug than dusting with sand, as these slugs, as soon as their skin is spoiled by being sanded, cast it off and go on with their work of destruction as freely as ever, and this they repeat. He remarked that it is a common error that all insects are pests to the cultivator. There are many parasites, or useful ones, which prey on our insect enemies. Out of 7,000 described insects in this country, only about 50 have proved destructive to our crops. Parasites are much more numerous. Among lepidopterous insects (butterflies, etc.), there are very few noxious species; many active friends are found among the Hymenoptera (wasps, etc.), the ichneumon flies pre-eminently so; and in the order Hemiptera (bugs proper) are several that destroy our enemies. Hence the very common error that birds which destroy insects are beneficial to us, as they are more likely to destroy our insect friends than the fewer enemies. Those known as flycatchers may do neither harm nor good; so far as they eat the wheat-midge and Hessian fly they confer a positive benefit; in other instances they destroy both friends and enemies. Birds that are only partly insectivorous, and which eat grain and fruit, may need further inquiry. Prof. S. had examined the stomachs of many such birds, and particularly of the American robin, and the only curculio he ever found in any of these was a single one in a whole cherry which the bird had bolted entire. Robins had proved very destructive to his grapes, but had not assisted at all in protecting his cabbages growing alongside his fruit garden. These vegetables were nearly destroyed by the larvae of the cabbage fly, which would have afforded the birds many fine, rich meals. This comparatively feeble insect has been allowed by the throngs of birds to spread over the whole continent. A naturalist in one of the Western States had examined several species of the thrush, and found they had eaten mostly that class of insects known as our friends.

Prof. S. spoke of the remedies for root lice, among which were hot water and bisulphide of carbon. Hot water will get cold before it can reach the smaller roots, however efficient it may be showered on leaves. Bisulphide of carbon is very volatile, inflammable, and sometimes explosive, and must be handled with great care. It permeates the soil, and if in sufficient quantity may be effective in destroying the phylloxera; but its cost and dangerous character prevent it from being generally recommended.

Paris green is most generally useful for destroying insects. As sold to purchasers, it is of various grades of purity. The highest in price is commonly the purest, and really the cheapest. A difficulty with this variable quality is that it cannot be properly diluted with water, and those who buy and use a poor article and try its efficacy, will burn or kill their plants when they happen to use a stronger, purer, and more efficient one. Or, if the reverse is done, they may pronounce it a humbug from the resulting failure. One teaspoonful, if pure, is enough for a large pail of water; or if mixed with flour, there should be forty or fifty times as much. Water is best, as the operator will not inhale the dust. London purple is another form of the arsenic, and has very variable qualities of the poison, being merely refuse matter from manufactories. It is more soluble than Paris green, and hence more likely to scorch plants. On the whole, Paris green is much the best and most reliable for common use.