полная версия

полная версияComic History of the United States

Farmers and laborers of those days wore green or red baize in the shape of jackets, and their breeches were made of leather or bed-ticking. Our ancestors dressed plainly, and a man who could not make over two hundred pounds per year was prohibited from dressing up or wearing lace worth over two shillings per yard. It was a pretty sad time for literary men, as they were thus compelled to wear clothing like the common laborers.

Lord Cornwallis once asked his aidy kong why the American poet always had such an air of listening as if for some expected sound. "I give it up," retorted the aidy kong. "It is," said Lord Cornwallis, as he took a large drink from a jug which he had tied to his saddle, "because he is trying to see if he cannot hear his bed-ticking." On the following day he surrendered his army, and went home to spring his bon-mot on George III.

Yet the laws were very stringent in other respects besides apparel. A man was publicly whipped for killing a fowl on the Sabbath in New England. In order to keep a tavern and sell rum, one had to be of good moral character and possess property, which was a good thing. The names of drunkards were posted up in the alehouses, and the keepers forbidden to sell them liquor. No person under twenty years of age could use tobacco in Connecticut without a physician's order, and no one was allowed to use it more than once a day, and then not within ten miles of any house. It was a common thing to see large picnic-parties going out into the backwoods of Connecticut to smoke.

(Will the reader excuse me a moment while I light up a peculiarly black and redolent pipe?)

LORD CORNWALLIS'S CONUNDRUM.

Only the gentry were called Mr. and Mrs. This included the preacher and his wife. A friend of mine who is one of the gentry of this century got on the trail of his ancestry last spring, and traced them back to where they were not allowed to be called Mr. and Mrs., and, fearing he would fetch up in Scotland Yard if he kept on, he slowly unrolled the bottoms of his trousers, got a job on the railroad, and since then his friends are gradually returning to him. He is well pleased now, and looks humbly gratified even if you call him a gent.

The Scriptures were literally interpreted, and the Old Testament was read every morning, even if the ladies fainted.

The custom yet noticed sometimes in country churches and festive gatherings of placing the males and females on opposite sides of the room was originated not so much as a punishment to both, as to give the men an opportunity to act together when the red brother felt ill at ease.

I am glad the red brother does not molest us nowadays, and make us sit apart that way. Keep away, red brother; remain on your reservation, please, so that the pale-face may sit by the loved one and hold her little soft hand during the sermon.

Church services meant business in those days. People brought their dinners and had a general penitential gorge. Instrumental music was proscribed, as per Amos fifth chapter and twenty-third verse, and the length of prayer was measured by the physical endurance of the performer.

The preacher often boiled his sermon down to four hours, and the sexton up-ended the hourglass each hour. Boys who went to sleep in church were sand-bagged, and grew up to be border murderers.

New York people were essentially Dutch. New York gets her Santa Claus, her doughnuts, crullers, cookies, and many of her odors, from the Dutch. The New York matron ran to fine linen and a polished door-knocker, while the New England housewife spun linsey-woolsey and knit "yarn mittens" for those she loved.

Philadelphia was the largest city in the United States, and was noted for its cleanliness and generally sterling qualities of mind and heart, its Sabbath trance and clean white door-steps.

The Southern Colonies were quite different from those of the North. In place of thickly-settled towns there were large plantations with African villages near the house of the owner. The proprietor was a sort of country squire, living in considerable comfort for those days. He fed and clothed everybody, black or white, who lived on the estate, and waited patiently for the colored people to do his work and keep well, so that they would be more valuable. The colored people were blessed with children at a great rate, so that at this writing, though voteless, they send a large number of members to Congress. This cheers the Southern heart and partially recoups him for his chickens. (See Appendix.)

The South then, as now, cured immense quantities of tobacco, while the North tried to cure those who used it.

Washington was a Virginian. He packed his own flour with his own hands, and it was never inspected. People who knew him said that the only man who ever tried to inspect Washington's flour was buried under a hill of choice watermelons at Mount Vernon.

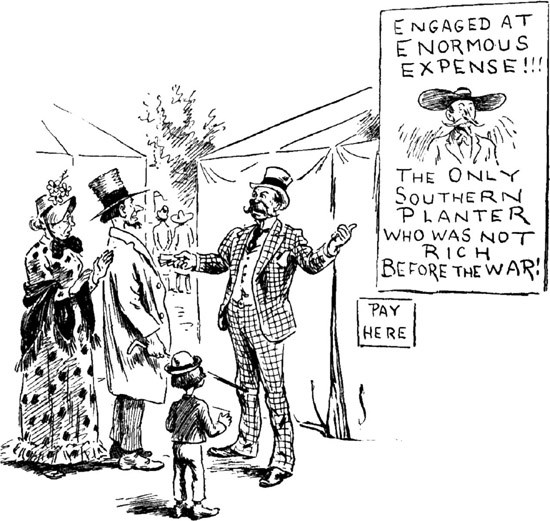

Along the James and Rappahannock the vast estates often passed from father to son according to the law of entail, and such a thing as a poor man "prior to the war" must have been unknown.

NOT RICH BEFORE THE WAR.

Education, however, flourished more at the North, owing partly to the fact that the people lived more in communities. Governor Berkeley of Virginia was opposed to free schools from the start, and said, "I thank God there are no free schools nor printing-presses here, and I hope we shall not have them these hundred years." His prayer has been answered.

CHAPTER XIV.

THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR

William Pitt was partly to blame for the Revolutionary War. He claimed that the Colonists ought not to manufacture so much as a horseshoe nail except by permission of Parliament.

It was already hard enough to be a colonist, without the privilege of expressing one's self even to an Indian without being fined. But when we pause to think that England seemed to demand that the colonist should take the long wet walk to Liverpool during a busy season of the year to get his horse shod, we say at once that P. Henry was right when he exclaimed that the war was inevitable and moved that permission be granted for it to come.

Then came the Stamp Act, making almost everything illegal that was not written on stamp paper furnished by the maternal country.

John Adams, Patrick Henry, and John Otis made speeches regarding the situation. Bells were tolled, and fasting and prayer marked the first of November, the day for the law to go into effect.

These things alarmed England for the time, and the Stamp Act was repealed; but the king, who had been pretty free with his money and had entertained a good deal, began to look out for a chance to tax the Colonists, and ordered his Exchequer Board to attend to it.

PATRICK HENRY.

Patrick Henry got excited, and said in an early speech, "Cæsar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third–" Here he paused and took a long swig of pure water, and added, looking at the newspaper reporters, "If this be treason, make the most of it." He also said that George the Third might profit by their example. A good many would like to know what he started out to say, but it is too hard to determine.

Boston ladies gave up tea and used the dried leaves of the raspberry, and the girls of 1777 graduated in homespun. Could the iron heel of despotism crunch such a spirit of liberty as that? Scarcely. In one family at Newport four hundred and eighty-seven yards of cloth and thirty-six pairs of stockings were spun and made in eighteen months.

When the war broke out it is estimated that each Colonial soldier had twenty-seven pairs of blue woollen socks with white double heels and toes. Does the intelligent reader believe that "Tommy Atkins," with two pairs of socks "and hit a-rainin'," could whip men with twenty-seven pairs each? Not without restoratives.

Troops were now sent to restore order. They were clothed by the British government, but boarded around with the Colonists. This was irritating to the people, because they had never met or called on the British troops. Again, they did not know the troops were coming, and had made no provision for them.

THE BRITISH BOARDING 'ROUND.

Boston was considered the hot-bed of the rebellion, and General Gage was ordered to send two regiments of troops there. He did so, and a fight ensued, in which three citizens were killed.

In looking over this incident, we must not forget that in those days three citizens went a good deal farther than they do now.

The fight, however, was brief. General Gage, getting into a side street, separated from his command, and, coming out on the Common abruptly, he tried eight or nine more streets, but he came out each time on the Common, until, torn with conflicting emotions, he hired a Herdic, which took him around the corner to his quarters.

On December 16, 1773, occurred the tea-party at Boston, which must have been a good deal livelier than those of to-day. The historian regrets that he was not there; he would have tried to be the life of the party.

England had finally so arranged the price of tea that, including the tax, it was cheaper in America than in the old country. This exasperated the patriots, who claimed that they were confronted by a theory and not a condition. At Charleston this tea was stored in damp cellars, where it spoiled. New York and Philadelphia returned their ships, but the British would not allow any shenanegin', as George III. so tersely termed it, in Boston.

Therefore a large party met in Faneuil Hall and decided that the tea should not be landed. A party made up as Indians, and, going on board, threw the tea overboard. Boston Harbor, as far out as the Bug Light, even to-day, is said to be carpeted with tea-grounds.

George III. now closed Boston harbor and made General Gage Governor of Massachusetts. The Virginia Assembly murmured at this, and was dissolved and sent home without its mileage.

BOSTON TEA-PARTY, 1773.

Those opposed to royalty were termed Whigs, those in favor were called Tories. Now they are called Chappies or Authors.

On the 5th of September, 1774, the first Continental Congress assembled at Philadelphia and was entertained by the Clover Club. Congress acted slowly even then, and after considerable delay resolved that the conduct of Great Britain was, under the circumstances, uncalled for. It also voted to hold no intercourse with Great Britain, and decided not to visit Shakespeare's grave unless the mother-country should apologize.

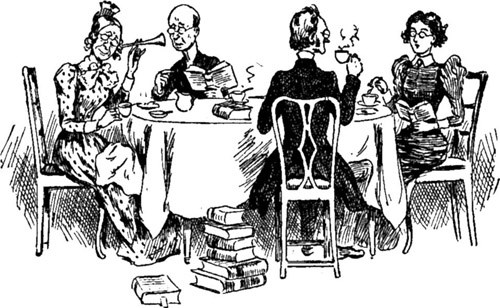

BOSTON TEA PARTY, 1893.

In 1775, on the 19th of April, General Gage sent out troops to see about some military stores at Concord, but at Lexington he met with a company of minute-men gathering on the village green. Major Pitcairn, who was in command of the Tommies, rode up to the minute-men, and, drawing his bright new Sheffield sword, exclaimed, "Disperse, you rebels! throw down your arms and disperse!" or some such remark as that.

The Americans hated to do that, so they did not. In the skirmish that ensued, seven of their number were killed.

Thus opened the Revolutionary War,—a contest which but for the earnestness and irritability of the Americans would have been extremely brief. It showed the relative difference between the fighting qualities of soldiers who fight for two pounds ten shillings per month and those who fight because they have lost their temper.

The regulars destroyed the stores, but on the way home they found every rock-pile hid an old-fashioned gun and minute-man. This shows that there must have been an enormous number of minute-men then. All the English who got back to Boston were those who went out to reinforce the original command.

The news went over the country like wildfire. These are the words of the historian. Really, that is a poor comparison, for wildfire doesn't jump rivers and bays, or get up and eat breakfast by candle-light in order to be on the road and spread the news.

General Putnam left a pair of tired steers standing in the furrow, and rode one hundred miles without feed or water to Boston.

Twenty thousand men were soon at work building intrenchments around Boston, so that the English troops could not get out to the suburbs where many of them resided.

GENERAL PUTNAM LEAVING A PAIR OF TIRED STEERS.

I will now speak of the battle of Bunker Hill.

This battle occurred June 17. The Americans heard that their enemy intended to fortify Bunker Hill, and so they determined to do it themselves, in order to have it done in a way that would be a credit to the town.

A body of men under Colonel Prescott, after prayer by the President of Harvard University, marched to Charlestown Neck. They decided to fortify Breed's Hill, as it was more commanding, and all night long they kept on fortifying. The surprise of the English at daylight was well worth going from Lowell to witness.

Howe sent three thousand men across and formed them on the landing. He marched them up the hill to within ten rods of the earth-works, when it occurred to Prescott that it would now be the appropriate thing to fire. He made a statement of that kind to his troops, and those of the enemy who were alive went back to Charlestown. But that was no place for them, as they had previously set it afire, so they came back up the hill, where they were once more well received and tendered the freedom of a future state.

GENERAL HOWE'S SUGGESTION.

PUTNAM'S FLIGHT.

Three times the English did this, when the ammunition in the fortifications gave out, and they charged with fixed bayonets and reinforcements.

The Americans were driven from the field, but it was a victory after all. It united the Colonies and made them so vexed at the English that it took some time to bring on an era of good feeling.

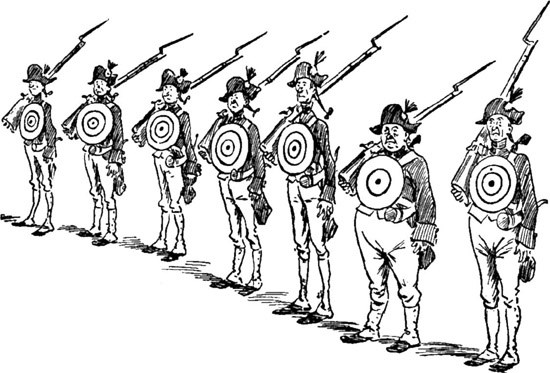

Lord Howe, referring afterwards to this battle, said that the Americans did not stand up and fight like the regulars, suggesting that thereafter the Colonial army should arrange itself in the following manner before a battle!

However, the suggestion was not acted on. The Colonial soldiers declined to put on a bright red coat and a pill-box cap, that kept falling off in battle, thus delaying the carnage, but preferred to wear homespun which was of a neutral shade, and shoot their enemy from behind stumps. They said it was all right to dress up for a muster, but they preferred their working-clothes for fighting. After the war a statistician made the estimate that nine per cent. of the British troops were shot while ascertaining if their caps were on straight.4

General Israel Putnam was known as the champion rough rider of his day, and once when hotly pursued rode down three flights of steps, which, added to the flight he made from the English soldiers, made four flights. Putnam knew not fear or cowardice, and his name even to-day is the synonyme for valor and heroism.

FRANKLIN'S MORNING HUNT FOR HIS SHOES.

CHAPTER XV.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, LL.D., PH.G., F.R.S., ETC

It is considered advisable by the historian at this time to say a word regarding Dr. Franklin, our fellow-townsman, and a journalist who was the Charles A. Dana of his time.

THE PRINTER'S TOWEL.

Franklin's memory will remain green when the names of the millionaires of to-day are forgotten. Coextensive with the name of E. Rosewater of the Omaha Bee we will find that of Benjamin Franklin, whose bust sits above the fireplace of the writer at this moment, while a large Etruscan hornet is making a phrenological examination of same.

But let us proceed to more fully mark out the life and labors of this remarkable man.

Benjamin Franklin, formerly of Boston, came very near being an only child. If seventeen children had not come to bless the home of Benjamin's parents they would have been childless. Think of getting up in the morning and picking out your shoes and stockings from among seventeen pairs of them!

FRANKLIN AS FOREMAN.

Imagine yourself a child, gentle reader, in a family where you would be called upon every morning to select your own cud of spruce gum from a collection of seventeen similar cuds stuck on a window-sill! And yet Benjamin Franklin never murmured or repined. He desired to go to sea, and to avoid this he was apprenticed to his brother James, who was a printer.

It is said that Franklin at once took hold of the great Archimedean lever, and jerked it early and late in the interests of freedom.

It is claimed that Franklin, at this time, invented the deadly weapon known as the printer's towel. He found that a common crash towel could be saturated with glue, molasses, antimony, concentrated lye, and roller-composition, and that after a few years of time and perspiration it would harden so that "A Constant Reader" or "Veritas" could be stabbed with it and die soon.

Many believe that Franklin's other scientific experiments were productive of more lasting benefit to mankind than this, but I do not agree with them.

His paper was called the New England Courant. It was edited jointly by James and Benjamin Franklin, and was started to supply a long-felt want.

Benjamin edited it a part of the time, and James a part of the time. The idea of having two editors was not for the purpose of giving volume to the editorial page, but it was necessary for one to run the paper while the other was in jail.

FRANKLIN EXPERIMENTING WITH LIGHTNING.

In those days you could not sass the king, and then, when the king came in the office the next day and stopped his paper and took out his ad., put it off on "our informant" and go right along with the paper. You had to go to jail, while your subscribers wondered why their paper did not come, and the paste soured in the tin dippers in the sanctum, and the circus passed by on the other side.

How many of us to-day, fellow-journalists, would be willing to stay in jail while the lawn festival and the kangaroo came and went? Who of all our company would go to a prison-cell for the cause of freedom while a double-column ad. of sixteen aggregated circuses, and eleven congresses of ferocious beasts, fierce and fragrant from their native lair, went by us?

At the age of seventeen Ben got disgusted with his brother, and went to Philadelphia and New York, where he got a chance to "sub" for a few weeks and then got a regular "sit."

Franklin was a good printer, and finally got to be a foreman. He made an excellent foreman, sitting by the hour in the composing-room and spitting on the stove, while he cussed the make-up and press-work of the other papers. Then he would go into the editorial rooms and scare the editors to death with a wild shriek for more copy.

He knew just how to conduct himself as a foreman so that strangers would think he owned the paper.

In 1730, at the age of twenty-four, Franklin married, and established the Pennsylvania Gazette. He was then regarded as a great man, and almost every one took his paper.

Franklin grew to be a great journalist, and spelled hard words with great fluency. He never tried to be a humorist in any of his newspaper work, and everybody respected him.

Along about 1746 he began to study the habits and construction of lightning, and inserted a local in his paper in which he said that he would be obliged to any of his readers who might notice any new or odd specimens of lightning, if they would send them in to the Gazette office for examination.

Every time there was a thunderstorm Franklin would tell the foreman to edit the paper, and, armed with a string and an old door-key, he would go out on the hills and get enough lightning for a mess.

FRANKLIN VISITING GEORGE III.

In 1753 Franklin was made postmaster of the Colonies. He made a good Postmaster-General, and people say there were fewer mistakes in distributing their mail then than there have ever been since. If a man mailed a letter in those days, old Ben Franklin saw that it went to where it was addressed.

Franklin frequently went over to England in those days, partly on business and partly to shock the king. He liked to go to the castle with his breeches tucked in his boots, figuratively speaking, and attract a great deal of attention.

It looked odd to the English, of course, to see him come into the royal presence, and, leaning his wet umbrella up against the throne, ask the king, "How's trade?"

FRANKLIN ENTERING PHILADELPHIA.

Franklin never put on any frills, but he was not afraid of a crowned head. He used to say, frequently, that a king to him was no more than a seven-spot.

He did his best to prevent the Revolutionary War, but he couldn't do it. Patrick Henry had said that the war was inevitable, and had given it permission to come, and it came.

He also went to Paris, and got acquainted with a few crowned heads there. They thought a good deal of him in Paris, and offered him a corner lot if he would build there and start a paper. They also promised him the county printing; but he said, No, he would have to go back to America or his wife might get uneasy about him. Franklin wrote "Poor Richard's Almanac" in 1732 to 1757, and it was republished in England.

Franklin little thought, when he went to the throne-room in his leather riding-clothes and hung his hat on the throne, that he was inaugurating a custom of wearing groom clothes which would in these days be so popular among the English.

Dr. Franklin entered Philadelphia eating a loaf of bread and carrying a loaf under each arm, passing beneath the window of the girl to whom he afterwards gave his hand in marriage.

Nearly everybody in America, except Dr. Mary Walker, was once a poor boy.

CHAPTER XVI.

THE CRITICAL PERIOD

Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold on the 10th of May led two small companies to Ticonderoga, a strong fortress tremendously fortified, and with its name also across the front door. Ethan Allen, a brave Vermonter born in Connecticut, entered the sally-port, and was shot at by a guard whose musket failed to report. Allen entered and demanded the surrender of the fortress.

"By whose authority?" asked the commandant.

"By the authority of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress," said Allen, brandishing his naked sword at a great rate.

"Very well," said the officer: "if you put it on those grounds, all right, if you will excuse the appearance of things. We were just cleaning up, and everything is by the heels here."

"Never mind," said Allen, who was the soul of politeness. "We put on no frills at home, and so we are ready to take things as we find them."