полная версия

полная версияComic History of the United States

Oglethorpe wore a wig, but was otherwise one of our greatest minds. It is said that anybody at a distance of two miles on a clear day could readily distinguish that it was a wig, and yet he died believing that no one had ever probed his great mystery and that his wig would rise with him at the playing of the last trump.

BELIEVING HIS WIG WOULD RISE WITH HIM.

King George's War, which extended over four years, succeeded, but did not amount to anything except the capture of Cape Breton by English and Colonial troops. Cape Breton was called the Gibraltar of America; but a Yankee farmer who has raised flax on an upright farm for twenty years does not mind scaling a couple of Gibraltars before breakfast; so, without any West Point knowledge regarding engineering, they walked up the hill, and those who were alive when they got to the top took it. It was no Balaklava business and no dumb animal show, but simply revealed the fact that brave men fighting for their eight-dollar homes and a mass of children are disagreeable people to meet on the battle-field.

The French and Indian War lasted nine years,—viz., from 1754 to 1763. From Quebec to New Orleans the French owned the land, and mixed up a good deal socially with the Indians, so that the slender settlement along the coast had arrayed against it this vast line of northern and western forts, and the Indians, who were mostly friendly with the French, united with them in several instances and showed them some new styles of barbarism which up to that time they had never known about.

The half-breed is always half French and half Indian.

The English owned all lands lying on one side of the Ohio, the French on the other, which led a great chief to make a P. P. C. call on Governor Dinwiddie, and during the conversation to inquire with some naïveté where the Indian came in. No answer was ever received.

We pause here to ask the question, Why did the pale-face usurp the lands of the Indians without remuneration? It was because the Indian was not orthodox. He may have been lazy from a Puritanical stand-point, and he may also have hunted on the twenty-seventh Sunday after Easter; but still was it not right that he should have received a dollar or two per county for the United States? No one would have felt it, and possibly it might have saved the lives of innocent people.

Verbum sap., however, comes in here with peculiar appropriateness, and the massive-browed historian passes on.

The French had three forts along in the Middle States, as they are now called, and Western Pennsylvania; and George Washington, of whom more will be said in the twelfth chapter, was sent to ask the French to remove these forts. He started at once.

PLEASURE OF BEING ARRESTED IN PARIS.

The commanders were some of them arrogant, but the general, St. Pierre, treated him with great respect, refusing, however, to yield the ground discovered by La Salle and Marquette. The author had the pleasure of being arrested in Paris in 1889, and he feels of a truth, as he often does, that there can be no more polite people in the world than the French. Arrested under all circumstances and in many lands, the author can place his hand on his heart and say that he would go hundreds of miles to be arrested by a John Darm.

Washington returned four hundred miles through every kind of danger, including a lunch at Altoona, where he stopped twenty minutes.

The following spring Washington was sent under General Fry to drive out the French, who had started farming at Pittsburg. Fry died, and Washington took command. He liked it very much. After that Washington took command whenever he could, and soon rose to be a great man.

GENERAL BRADDOCK SCORNING WASHINGTON'S ADVICE.

The first expedition against Fort Duquesne (pronounced du-kane) was commanded by General Braddock, whose portrait we are able to give, showing him at the time he did not take Washington's advice in the Duquesne matter. Later we show him as he appeared after he had abandoned his original plans and immediately after not taking Washington's advice.

"The Indians," said Braddock, "may frighten Colonial troops, but they can make no impression on the king's regulars. We are alike impervious to fun or fear."

Braddock thought of fighting the Indians by manœuvring in large bodies, but the first body to be manœuvred was that of General Braddock, who perished in about a minute.

We give the reader, above, an idea of Braddock's soldierly bearing after he had been manœuvring a few times.

It was then that Washington took command, as was his custom, and began to fight the Indians and French as one would hunt varmints in Virginia.

Braddock's men fired by platoons into the trees and tore a few holes in the State line, but when most of the Colonial troops were dead the regulars presented their tournures to the foe and fled as far as Philadelphia, where they each took a bath and had some laundry-work done.

GENERAL BRADDOCK AFTER SCORNING WASHINGTON'S ADVICE.

General Forbes took command of the second expedition. He spent most of his time building roads.

Time passed on, and Forbes built viaducts, conduits, culverts, and rustic bridges, till it was November, and they were yet fifty miles from the fort. He then decided to abandon the expedition, on account of the cold, and also fearing that he had not made all of his bridges wide enough so that he could take the captured fort home with him.

Washington, however, though only an aidy kong of General Forbes, decided to take command. His mother had said to him over and over, "George, in an emergency always take command." He done so, as General Rusk would say. As he approached, the French set fire to the fort, and retreated, together with the Indians and Molly Maguires.

Pittsburg now stands on this historic ground, and is one of the most delightful cities of America.

Many other changes were going on at this time. The English got possession of Acadia and the French forts at the head of the Bay of Fundy.

In 1757 General Loudon collected an army for an attack on Louisburg. He drilled his troops all summer, and then gave up the attack because he learned that the French had one more skiff than he had.

The Loudons of America at the time of this writing are more quiet and sensible regarding their ancestry than any of the doodle-bug aristocracy of our promoted peasantry and the crested Yahoos of our cowboy republic.

The Loudons—or Lowdowns—of America had a very large family. Some of them changed their names and moved.

The next year after the fox pass of General Loudon, Amherst and Wolfe took possession of the entire island.

About the time of Braddock's justly celebrated expedition another started out for Crown Point. The French, under Dieskau (pronounced dees-kow), met the army composed of Colonial troops in plain clothes, together with the regular troops led by officers with drawn swords and overdrawn salaries. The regular general, seeing that the battle was lost, excused himself and retired to his tent, owing to an ingrowing nail which had annoyed him all day. Lyman, the Colonial officer now took command, and wrung victory from the reluctant jaws of defeat. For this Johnson, the English general, received twenty-five thousand dollars and a baronetcy, while Lyman received a plated butter-dish and a bass-wood what-not. But Lyman was a married man, and had learned to take things as they came.

Four months prior to the capture of Duquesne, one thousand boats loaded with soldiers, each with a neat little lunch-basket and a little flag to wave when they hurrahed for the good kind man at the head of the picnic,—viz., General Abercrombie,—sailed down Lake George to get a whiff of fresh air and take Ticonderoga.

When they arrived, General Abercrombie took out a small book regarding tactics which he had bought on the boat, and, after refreshing his memory, ordered an assault. He then went back to see how his rear was, and, finding it all right, he went back still farther, to see if no one had been left behind.

ABERCROMBIE WENT BACK TO THE REAR.

Abercrombie never forgot or overlooked any one. He wanted all of his pleasure-party to be where they could see the fight.

In that way he missed it himself. I would hate to miss a fight that way.

The Abercrombies of America mostly trace their ancestry back by a cut-off avoiding the general's line.

Niagara had an expedition sent against it at the time of Braddock's trip. The commander was General Shirley, but he ran out of money while at the Falls and decided to return. This post did not finally surrender till 1759.

This gave the then West to the English. They had tried for one hundred and forty years to civilize it, but, alas, with only moderate success. Prosperous and happy even while sniping in their fox-hunting or canvas-back-duck clothes, these people feel somewhat soothed for their lack of culture because they are well-to-do.

In 1759 General Wolfe anchored off Quebec with his fleet and sent a boy up town to ask if there were any letters for him at the post-office, also asking at what time it would be convenient to evacuate the place. The reply came back from General Montcalm, an able French general, that there was no mail for the general, but if Wolfe was dissatisfied with the report he might run up personally and look over the W's.

Wolfe did so, taking his troops up by an unknown cow-path on the off side of the mountain during the night, and at daylight stood in battle-array on the Plains of Abraham. An attack was made by Montcalm as soon as he got over his wonder and surprise. At the third fire Wolfe was fatally wounded, and as he was carried back to the rear he heard some one exclaim,—

"They run! They run!"

"Who run?" inquired Wolfe.

"The French! The French!" came the reply.

"Now God be praised," said Wolfe, "I die happy."

Montcalm had a similar experience. He was fatally wounded. "They run! They run!" he heard some one say.

"Who run?" exclaimed Montcalm, wetting his lips with a lemonade-glass of cognac.

"We do," replied the man.

"Then so much the better," said Montcalm, as his eye lighted up, "for I shall not live to see Quebec surrendered."

This shows what can be done without a rehearsal; also how the historian has to control himself in order to avoid lying.

The death of these two brave men is a beautiful and dramatic incident in the history of our country, and should be remembered by every school-boy, because neither lived to write articles criticising the other.

Five days later the city capitulated. An attempt was made to recapture it, but it was not successful. Canada fell into the hands of the English, and from the open Polar Sea to the Mississippi the English flag floated.

What an empire!

What a game-preserve!

Florida was now ceded to the already cedy crown of England by Spain, and brandy-and-soda for the wealthy and bitter beer became the drink of the poor.

REMAINED BY IT TILL DEATH.

Pontiac's War was brought on by the Indians, who preferred the French occupation to that of the English. Pontiac organized a large number of tribes on the spoils plan, and captured eight forts. He killed a great many people, burned their dwellings, and drove out many more, but at last his tribes made trouble, as there were not spoils enough to go around, and his army was conquered. He was killed in 1769 by an Indian who received for his trouble a barrel of liquor, with which he began to make merry. He remained by the liquor till death came to his relief.

The heroism of an Indian who meets his enemy single-handed in that way, and, though greatly outnumbered, dies with his face to the foe, is deserving of more than a passing notice.

The French and Indian War cost the Colonists sixteen million dollars, of which the English repaid only five million. The Americans lost thirty thousand men, none of whom were replaced. They suffered every kind of horror and barbarity, written and unwritten, and for years their taxes were two-thirds of their income; and yet they did not murmur.

These were the fathers and mothers of whom we justly brag. These were the people whose children we are. What are inherited titles and ancient names many times since dishonored, compared with the heritage of uncomplaining suffering and heroism which we boast of to-day because those modest martyrs were working people, proud that by the sweat of their brows they wrung from a niggardly soil the food they ate, proud also that they could leave the plough to govern or to legislate, able also to survey a county or rule a nation.

CHAPTER XII.

PERSONALITY OF WASHINGTON

It would seem that a few personal remarks about George Washington at this point might not be out of place. Later on his part in this history will more fully appear.

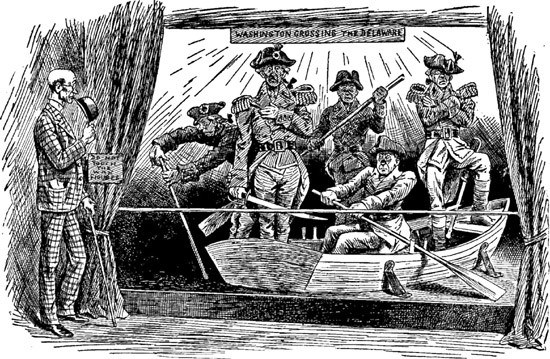

The author points with some pride to a study of Washington's great act in crossing the Delaware, from a wax-work of great accuracy. The reader will avoid confusing Washington with the author, who is dressed in a plaid suit and on the shore, while Washington may be seen in this end of the boat with the air of one who has just discovered the location of a glue-factory on the side of the river.

A directory of Washington's head-quarters has been arranged by the author of this book, and at a reunion of the general's body-servants to be held in the future the work will be on sale.

The name of George Washington has always had about it a glamour that made him appear more in the light of a god than a tall man with large feet and a mouth made to fit an old-fashioned full-dress pumpkin pie.

STUDY OF WASHINGTON CROSSING THE DELAWARE.

MY GREATEST WORK.

George Washington's face has beamed out upon us for many years now, on postage-stamps and currency, in marble and plaster and in bronze, in photographs of original portraits, paintings, and stereoscopic views. We have seen him on horseback and on foot, on the war-path and on skates, playing the flute, cussing his troops for their shiftlessness, and then, in the solitude of the forest, with his snorting war-horse tied to a tree, engaged in prayer.

We have seen all these pictures of George, till we are led to believe that he did not breathe our air or eat American groceries. But George Washington was not perfect. I say this after a long and careful study of his life, and I do not say it to detract the very smallest iota from the proud history of the Father of his Country. I say it simply that the boys of America who want to become George Washingtons will not feel so timid about trying it.

When I say that George Washington, who now lies so calmly in the lime-kiln at Mount Vernon, could reprimand and reproach his subordinates, at times, in a way to make the ground crack open and break up the ice in the Delaware a week earlier than usual, I do not mention it in order to show the boys of our day that profanity will make them resemble George Washington. That was one of his weak points, and no doubt he was ashamed of it, as he ought to have been. Some poets think that if they get drunk and stay drunk they will resemble Edgar A. Poe and George D. Prentice. There are lawyers who play poker year after year and get regularly skinned because they have heard that some of the able lawyers of the past century used to come home at night with poker-chips in their pockets.

WASHINGTON PLAYING THE FLUTE.

Whiskey will not make a poet, nor poker a great pleader. And yet I have seen poets who relied on the potency of their breath, and lawyers who knew more of the habits of a bobtail flush than they ever did of the statutes in such case made and provided.

George Washington was always ready. If you wanted a man to be first in war, you could call on George. If you desired an adult who would be first baseman in time of peace, Mr. Washington could be telephoned at any hour of the day or night. If you needed a man to be first in the hearts of his countrymen, George's post-office address was at once secured.

THE AWKWARD SQUAD.

Though he was a great man, he was once a poor boy. How often you hear that in America! Here it is a positive disadvantage to be born wealthy. And yet sometimes I wish they had experimented a little that way on me. I do not ask now to be born rich, of course, because it is too late; but it seems to me that, with my natural good sense and keen insight into human nature, I could have struggled along under the burdens and cares of wealth with great success. I do not care to die wealthy, but if I could have been born wealthy it seems to me I would have been tickled almost to death.

I love to believe that true greatness is not accidental. To think and to say that greatness is a lottery, is pernicious. Man may be wrong sometimes in his judgment of others, both individually and in the aggregate, but he who gets ready to be a great man will surely find the opportunity.

You will wonder whom I got to write this sentiment for me, but you will never find out.

In conclusion, let me say that George Washington was successful for three reasons. One was that he never shook the confidence of his friends. Another was that he had a strong will without being a mule. Some people cannot distinguish between being firm and being a big blue donkey.

Another reason why Washington is loved and honored to-day is that he died before we had a chance to get tired of him. This is greatly superior to the method adopted by many modern statesmen, who wait till their constituency weary of them, and then reluctantly pass away.

N. B.—Since writing the foregoing I have found that Washington was not born a poor boy,—a discovery which redounds greatly to his credit,—that he was able to accomplish so much, and yet could get his weekly spending money and sport a French nurse in his extreme youth.

B. N.CHAPTER XIII.

CONTRASTS WITH THE PRESENT DAY

Here it may be well to speak briefly of the contrast between the usages and customs of the period preceding the Revolution, and the present day. Some of these customs and regulations have improved with the lapse of time, others undoubtedly have not.

Two millions of people constituted the entire number of whites, while away to the westward the red brother extended indefinitely. Religiously they were Protestants, and essentially they were "a God-fearing people." Taught to obey a power they were afraid of, they naturally turned with delight to the service of a God whose genius in the erection of a boundless and successful hell challenged their admiration and esteem. So, too, their own executions of Divine laws were successful as they gave pain, and the most beautiful features of Christianity,—namely, love and charity,—according to history, were not cultivated very much.

There were in New England at one time twelve offences punishable with death, and in Virginia seventeen. This would indicate that the death-penalty is getting unpopular very fast, and that in the contiguous future humane people will wonder why murder should have called for murder, in this brainy, charitable, and occult age, in which man seems almost able to pry open the future and catch a glimpse of Destiny underneath the great tent that has heretofore held him off by means of death's prohibitory rates.

THE TOWN WATCHMAN.

In Hartford people had to get up when the town watchman rang his bell. The affairs of the family, and private matters too numerous to mention, were regulated by the selectmen. The catalogues of Harvard and Yale were regulated according to the standing of the family as per record in the old country, and not as per bust measurement and merit, as it is to-day.

Scolding women, however, were gagged and tied to their front doors, so that the populace could bite its thumb at them, and hired girls received fifty dollars a year, with the understanding that they were not to have over two days out each week, except Sunday and the days they had to go and see their "sick sisters."

Some cloth-weaving was indulged in, and homespun was the principal material used for clothing. Mrs. Washington had sixteen spinning-wheels in her house. Her husband often wore homespun while at home, and on rainy days sometimes placed a pair of home-made trousers of the barn-door variety in the Presidential chair.

Money was very scarce, and ammunition very valuable. In 1635 musket-balls passed for farthings, and to see a New England peasant making change with the red brother at thirty yards was a common and delightful scene.

The first press was set up in Cambridge in 1639, with the statement that it "had come to stay." Books printed in those days were mostly sermons filled with the most comfortable assurance that the man who let loose his intellect and allowed it to disbelieve some very difficult things would be essentially–well, I hate to say right here in a book what would happen to him.

BOOKS FILLED WITH ASSURANCES OF FUTURE DAMNATION.

The first daily paper, called The Federal Orrery, was issued three hundred years after Columbus discovered America. It was not popular, and killed off the news-boys who tried to call it on the streets: so it perished.

There was a public library in New York, from which books were loaned at fourpence ha'penny per week. New York thus became very early the seat of learning, and soon afterwards began to abuse the site where Chicago now stands.

Travel was slow, the people went on horseback or afoot, and when they could go by boat it was regarded as a success. Wagons finally made the trip from New York to Philadelphia in the wild time of forty-eight hours, and the line was called The Flying Dutchman, or some other euphonious name. Benjamin Franklin, whose biography occurs in Chapter XV., was then Postmaster-General.

He was the first bald-headed man of any prominence in the history of America. He and his daughter Sally took a trip in a chaise, looking over the entire system, and going to all offices. Nothing pleased the Postmaster-General like quietly slipping into a place like Sandy Bottom and catching the postmaster reading over the postal cards and committing them to memory.

Calfskin shoes up to the Revolution were the exclusive property of the gentry, and the rest wore cowhide and were extremely glad to mend them themselves. These were greased every week with tallow, and could be worn on either foot with impunity. Rights and lefts were never thought of until after the Revolutionary War, but to-day the American shoe is the most symmetrical, comfortable, and satisfactory shoe made in the world. The British shoe is said to be more comfortable. Possibly for a British foot it is so, but for a foot containing no breathing-apparatus or viscera it is somewhat roomy and clumsy.

CAUGHT BY FRANKLIN READING POSTAL CARDS.