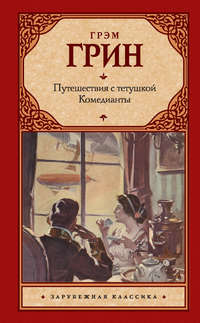

Полная версия

Travels with my aunt / Путешествие с тетушкой. Книга для чтения на английском языке

“‘It proves our point,’ Curran said. ‘Whoremongers and murderers and the rest – they all have souls, don’t they? They only have to repent, and it’s the same with dogs. The dogs who come to our church have repented. They don’t consort any more with whoremongers and sorcerers. They live with respectable people in Brunswick Square or Royal Crescent.’ Do you know that Curran was so little put off by the Apocalypse he actually preached a sermon on that very text, telling people that it was their responsibility to see that their dogs didn’t backslide? ‘Loose the lead and spoil the dog[56]’, he said. ‘There are only too many murderers in Brighton and whoremongers at the Metropole all ready to pick up what you loose. And us for sorcerers —’ Luckily Hatty, who was with us by that time, had not yet become a fortune-teller. It would have spoilt the image.”

“He was a good preacher?”

“It was music to hear him,” she said with happy regret, and we began to walk back towards the front; we could hear the shingle turning over from a long way away. “He was not exclusive,” my aunt said. “For him dogs were like the House of Israel, but he was an apostle also to the Gentiles – and the Gentiles, to Curran, included sparrows and parrots and white mice – not cats, cats he always regarded as Pharisees. Of course no cat dared come into the church with all those dogs around, but there was one who used to sit in the window of a house opposite and sneer when the congregation came out. Curran excluded fish too – it would be too shocking to eat something with a soul, he said. Elephants he had a very great feeling for, which was generous of him considering Hannibal had trodden on his toe. Let’s sit down here, Henry. I always find Guinness a little tiring.”

We sat down in a shelter. The lights ran out to sea along the Palace Pier and the edge of the water was white with phosphorescence. The waves were continually pulled up along the beach and pulled back as though someone were making a bed and couldn’t get the sheet to lie properly. A bit of pop music came from the dance hall standing there like a blockade ship a hundred yards out. This trip was quite an adventure, I thought to myself, little knowing how small a one it would seem in retrospect.

“I found a lovely piece about elephants once in Saint Francis de Sales,” Aunt Augusta said, “and Curran used it in his last sermon after all that business with the girls had upset me. I really think what he wanted was to tell me it was me he loved, but I was a hard young woman in those days and I wouldn’t listen. I’ve always kept the piece though in my purse and, when I read it, it’s not the elephant that I see now, it’s Curran. He was a fine big fellow – not as big as Wordsworth but a good deal more sensitive.”

She fumbled in her bag and found her purse. “You read it to me, dear, I can’t see properly in this light.”

I held the rather yellowed creased paper at an angle to catch one of the lights of the front. It wasn’t easy to read, though my aunt’s handwriting was young and bold, because of the creases. “‘The elephant,’” I read, “‘is only a huge animal, but he is the most worthy of beasts that lives on the earth, and the most intelligent. I will give you an example of his excellence; he…’” The writing ran along a crease and I couldn’t read it, but my aunt chimed gently in. “‘He never changes his mate and he tenderly loves the one of his choice.’ Go on, dear.”

“‘With whom,’” I read, “‘nevertheless he mates but every third year, and then for five days only and so secretly that he has never been seen to do so.’”

“He was trying to explain,” my aunt said, “I am sure of it now, that if he had been a little slack in his attentions[57], it was only because of the girls – he didn’t love me less.”

“‘But he is to be seen again on the sixth day, on which day, before doing anything else, he goes straight to some river wherein he bathes his whole body, for he has no desire to return to the herd until he has purified himself.’”

“Curran was always a clean man,” my aunt said. “Thank you, dear, you read it very well.”

“It doesn’t seem very applicable to dogs,” I said.

“He turned it so beautifully that no one noticed, and it was really directed at me. I remember he had a special dogs’ shampoo which had been blessed at the altar on sale outside the church door that Sunday.”

“What became of Curran?”

“I’ve no idea,” Aunt Augusta said. “He must have left his church, for he couldn’t have carried on without me. Hatty hadn’t the right touch for a deaconess. I dream of him sometimes – but he would be ninety years old now, and I find it hard to picture him as an old man. Well, Henry, I think it is time for us both to sleep.”

All the same, I found sleep difficult to attain, even in my comfortable bed at the Royal Albion. The lights of the Palace Pier sparkled on the ceiling, and round and round in my head went the figures of Wordsworth and Curran, the elephant and the dogs of Hove, the mystery of my birth, the ashes of my mother who was not my mother, and my father asleep in the bath. This was not the simple life which I had known at the bank, where I could judge a client’s character by his credits and debits. I had a sense of fear and exhilaration too, as the music pounded from the Pier and the phosphorescence rolled up the beach.

Chapter 7

The affair of my mother’s ashes was not settled so easily as I had anticipated (I call her my mother still, because at this period I had no real evidence that my aunt was telling me the truth). No urn was awaiting me in the house when I returned from Brighton, and so I rang up Scotland Yard and asked for Detective-Sergeant Sparrow. I was put on without delay to a voice which was distinctly not Sparrow’s. It sounded very similar to that of a rear-admiral whom I had once had as a client. (I was very glad when he changed his account to the National Provincial Bank, for he treated my clerks like ordinary seamen and myself like a sub-lieutenant who had been court-marchialled for keeping the mess books improperly.)

“Can I speak to Detective-Sergeant Sparrow?” I asked.

“On what business?” whoever it was rapped back.

“I have not yet received my mother’s ashes,” I said.

“This is Scotland Yard, Assistant Commissioner’s Office, and not a crematorium,” the voice replied and rang off.

It took me a long while (because of engaged lines) to get the same gritty voice on the line again.

“I want Detective-Sergeant Sparrow,” I said.

“On what business?”

I was ready this time and prepared to be ruder than the voice could be.

“Police business of course,” I said. “What other business do you deal in?” It was almost as though my aunt were speaking through me.

“Detective-Sergeant Sparrow is out. You had better leave a message.”

“Ask him to ring Mr. Pulling, Mr. Henry Pulling.”

“What address? What telephone number?” he snapped as though he suspected me to be some unsavoury police informer.

“He knows them both. I am not going to repeat them unnecessarily. Tell him I am disappointed at his failure to keep a solemn promise.” I rang off before the other had time for a word in reply. Going out to the dahlias, I gave myself the rare award of a satisfied smile. I had never spoken to the rear-admiral like that.

My new cactus dahlias were doing well, and after my trip to Brighton their names gave me some of the pleasure of travel: Rotterdam, a deeper red than a pillar-box, and Dentelle de Venise, with spikes sparkling like hoar-frost. I thought that next year I would plant some Pride of Berlin to make a trio of cities. The telephone disturbed my happy ruminations. It was Sparrow.

I said to him firmly, “I hope you have a good excuse for failing to return the ashes.”

“I certainly have, sir. There’s more Cannabis than ashes in your urn.”

“I don’t believe you. How could my mother possibly…?”

“We can hardly suspect your mother, sir, can we? As I told you, I think the man Wordsworth took advantage of your call[58]. Luckily for your story there are some human ashes in the urn, though Wordsworth must have dumped most of them down the sink to make room. Did you hear any sound of running water?”

“We were drinking whisky. He certainly filled a jug of water.”

“That must have been the moment[59], sir”.

“In any case, I would like to have back the ashes that remain.”

“It isn’t practicable, sir. Human ashes have a kind of sticky quality. They adhere very closely to any substance, which in this case is pot. I am sending you back the urn by registered post. I suggest, sir, that you place it just where you intended and forget the unfortunate circumstances.”

“But the urn will be empty.”

“Memorials are often detached from the remains of the deceised. War memorials are an example.”

“Well,” I said, “I suppose there’s nothing to be done. It won’t feel the same at all. I hope you don’t suspect my aunt had any hand in this[60]?”

“An old lady like that? Oh no, sir. She was obviously deceived by her valet.”

“What valet?”

“Why, Wordsworth, sir – who else?” I thought it best not to enlighten him about their relationship.

“My aunt thinks Wordsworth may be in Paris.”

“Very likely, sir.”

“What will you do about it?”

“There’s nothing we can do. He hasn’t committed an extraditable offence. Of course, if he ever returns… He has a British passport.” There was a note of malicious longing in Detective-Sergeant Sparrow’s voice that made me feel, for a moment, a partisan of Wordsworth.

I said, “I sincerely hope he won’t.”

“You surprise and disappoint me, sir.”

“Why?”

“I hadn’t taken you for one of that kind.”

“What kind?”

“People who talk about there being no harm in pot.”

“Is there?”

“From our experience, sir, nearly all the cases hooked on hard drugs began with pot.”

“And from my experience, Sparrow, all or nearly all the alcoholics I know have started with a small whisky or a glass of wine. I even had a client who was first hooked, as you call it, on mild and bitter. In the end, because of his frequent absences on a cure, he had to give his wife a power of attorney[61]”. I rang off. It occurred to me with a certain pleasure that I had sowed a little confusion in Detective-Sergeant Sparrow’s mind – not so much confusion on the subject of Cannabis but confusion about my character, the character of a retired bank manager. I discovered for the first time in myself a streak of anarchy. Had it been perhaps the result of my visit to Brighton or was it possibly my aunt’s influence (and yet I was not a man easily influenced), or some bacteria in the Pulling blood? I found a buried affection for my father reviving in me. He had been a very patient as well as a very sleepy man, and yet there was about his patience something unaccountable: it might well have been absence of mind rather than patience – or even indifference. He might have been all the time, without our knowing it, elsewhere. I remembered the ambiguous reproaches launched against him by my mother. They seemed to confirm my aunt’s story, for they possessed the nagging qualities of an unsatisfied woman. Imprisoned by ambitions which she had never realized, my mother had never known freedom. Freedom, I thought, comes only to the successful, and in his trade my father was a success. If a client didn’t like my father’s manner or his estimates, he could go elsewhere. My father wouldn’t have cared. Perhaps it is freedom, of speech and conduct, which is really envied by the unsuccessful, not money or even power.

It was with these muddled and unaccustomed ideas in my mind that I awaited the arrival of my aunt for dinner. We had arranged the rendezvous[62] before leaving the Brighton Belle at Victoria the day before. As soon as she arrived I told her about Sergeant Sparrow, but she treated my story with surprising indifference, saying only that Wordsworth should have been “more careful.” Then I took her out and showed her my dahlias.

“I have always preferred cut flowers,” she said, and I had a sudden vision of strange continental gentlemen offering her bouquets of roses and maidenhair fern bound up in tissue paper.

I pointed out to her the site where I had thought to put the urn in memory of my mother.

“Poor Angelica,” she said, “she never understood men,” and that was all. It was as though she had read my thoughts and commented on them.

I had dialled CHICKEN and the dinner arrived exactly as ordered, the main course only needing to be put into the oven for a few minutes while we ate the smoked salmon. Living alone, I had been a regular customer whenever there was a client to entertain or my mother on her weekly visit. Now for months I had neglected Chicken, for there were no longer any clients and my mother, during her last illness, had been too ill to make the journey from Golders Green.

We drank sherry with the smoked salmon, and as some small return for my aunt’s generosity to me in Brighton I had bought a bottle of burgundy, Chambertin 1959, Sir Arthur Keene’s favourite, to go with the chicken à la king. When the wine had spread a pleasant glow through both our minds my aunt reverted to my conversation with Sergeant Sparrow.

“He is determined,” she said, “that Wordsworth is the guilty party, yet it might equally well be one of us. I don’t think the sergeant is a racialist, but he is class-conscious, and though the smoking of pot depends on no class barrier, he prefers to think otherwise and to put the blame on poor Wordsworth.”

“You and I can give each other an alibi,” I said, “and Wordsworth did run away.”

“We could have been in collusion, and Wordsworth might be taking his annual holiday. No,” she went on, “the mind of a policeman is set firmly in a groove. I remember once when I was in Tunis a travelling company was there who were playing Hamlet in Arabic. Someone saw to it that in the Interlude the Player King was really killed – or rather not quite killed but severely damaged in the right ear – by molten lead. And who do you suppose the police at once suspected? Not the man who poured the lead in, although he must have been aware that the ladle wasn’t empty and was hot to the touch. Oh no, they knew Shakespeare’s play too well for that, and so they arrested Hamlet’s uncle.”

“What a lot of travelling you have done in your day, Aunt Augusta.”

“I haven’t reached nightfall yet[63]”, she said. “If I had a companion I would be off tomorrow, but I can no longer lift a heavy suitcase, and there is a distressing lack of porters nowadays. As you noticed in Victoria.”

“We might one day,” I said, “continue our seaside excursions. I remember many years ago visiting Weymouth. There was a very pleasant green statue of George III[64] on the front”.

“I have booked two couchettes[65] a week from today on the Orient Express.”

I looked at her in amazement. “Where to?” I asked.

“Istanbul of course.”

“But it takes days…”

“Three nights to be exact.”

“If you want to go to Istanbul surely it would be easier and less expensive to fly?”

“I only take a plane,” my aunt said, “when there is no alternative means of travel.”

“It’s really quite safe.”

“It’s a matter of choice, not nerves,” Aunt Augusta said. “I knew Wilbur Wright[66] very well indeed at one time. He took me for several trips. I always felt quite secure in his contraptions. But I cannot bear being spoken to all the timely irrelevant loud-speakers. One is not badgered at a railway station. An airport always reminds me of a Butlin’s Camp.”

“If you are thinking of me as a companion…”

“Of course I am, Henry.”

“I’m sorry, Aunt Augusta, but a bank manager’s pension is not a generous one.”

“I shall naturally pay all expenses. Give me another glass of wine, Henry. It’s excellent.”

“I’m not really accustomed to foreign travel. You’d find me…”

“You will take to it[67] quickly enough in my company. The Pullings have all been great travellers. I think I must have caught the infection through your father.”

“Surely not my father… He never travelled further than Central London.”

“He travelled from one woman to another, Henry, all through his life. That comes to much the same thing. New landscapes, new customs. The accumulation of memories. A long life is not a question of years. A man without memories might reach the age of a hundred and feel that his life had been a very brief one. Your father once said to me, ‘The first girl I ever slept with was called Rose. Oddly enough she worked in a flower shop. It really seems a century ago.’ And then there was your uncle…”

“I didn’t know I had an uncle.”

“He was fifteen years older than your father and he died when you were very young.”

“He was a great traveller?”

“It took an odd form,” my aunt said, “in the end.” I wish I could reproduce more clearly the tones of her voice. She enjoyed talking, she enjoyed telling a story. She formed her sentences carefully like a slow writer who foresees ahead of him the next sentence and guides his pen towards it. Not for her the broken phrase, the lapse of continuity. There was something classically precise, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say old-world, in her diction. The bizarre phrase, and occasionally, it must be agreed, a shocking one, gleamed all the more brightly from the old setting. As I grew to know her better, I began to regard her as bronze rather than brazen, a bronze which has been smoothed and polished by touch, like the horse’s knee in the lounge of the Hôtel de Paris in Monte Carlo, which she once described to me, caressed by generations of gamblers.

“Your uncle was a bookmaker known as Jo,” Aunt Augusta said. “A very fat man. I don’t know why I say that, but I have always liked fat men. They have given up all unnecessary effort, for they have had the sense to realize that women do not, as men do, fall in love with physical beauty. Curran was stout and so was your father. It’s easier to feel at home with a fat man.[68] Perhaps travelling with me, you will put on a little weight yourself. You had the misfortune to choose a nervous profession.”

“I have certainly never banted for the sake of a woman,” I said jokingly.

“You must tell me all about your women one day. In the Orient Express we shall have plenty of time for talk. But now I am speaking to you of your Uncle Jo. His was a very curious case. He made a substantial fortune as a bookmaker, yet more and more his only real desire was to travel. Perhaps the horses continually running by, while he had to remain stationary on a little platform with a signboard HONEST JO PULLING, made him restless. He used to say that one race meeting merged into another and life went by as rapidly as a yearling out of Indian Queen. He wanted to slow life up and he quite rightly felt that by travelling he would make time move with less rapidity. You have noticed it yourself, I expect, on a holiday. If you stay in one place, the holiday passes like a flash, but if you go to three places, the holiday seems to last at least three times as long.”

“Is that why you have travelled so much, Aunt Augusta?”

“At first I travelled for my living,” Aunt Augusta replied. “That was in Italy. After Paris, after Brighton. I had left home before you were born. Your father and mother wished to be alone, and in any case I never got on very well with Angelica. The two A’s we were always called. People used to say my name fitted me because I seemed proud as a young girl, but no one said my sister’s name fitted her. A saint she may well have been[69], but a very severe saint. She was certainly not angelic.”

One of the few marks of age which I noticed in my aunt was her readiness to abandon one anecdote while it was yet unfinished for another. Her conversation was rather like an American magazine where you have to pursue a story, skipping from page twenty to page ninety-eight and turning over all kinds of subjects in between: childhood delinquency, some novel cocktail recipes, the love life of a film star, and even quite a different fiction from the one so abruptly interrupted.

“The question of names,” my aunt said, “is an interesting one. Your own Christian name is safe and colourless. It is better than being given a name like Ernest, which has to be lived up to. I once knew a girl called Comfort and her life was a very sad one. Unhappy men were constantly attracted to her simply by reason of her name, when all the time, poor dear, it was really she who needed the comfort from them. She fell unhappily in love with a man called Courage, who was desperately afraid of mice, but in the end she married a man called Payne and killed herself – in what Americans call a comfort station[70]. I would have thought it a funny story if I hadn’t known her.”

“You were telling me about my Uncle Jo,” I said.

“I know that. I was saying that he wanted to make life last longer. So he decided on a tour round the world (there were no currency restrictions in those days), and he began his tour curiously enough with the Simplon Orient, the train we are travelling by next week. From Turkey he planned to go to Persia, Russia, India, Malaya, Hong Kong, China, Japan, Hawaii, Tahiti, U.S.A., South America, Australia, New Zealand perhaps – somewhere he intended to take a boat home. Unfortunately he was carried off the train at Venice right at the start, on a stretcher, after a stroke.”

“How very sad.”

“It didn’t alter at all his desire for a long life. I was working in Venice at the time, and I went to see him. He had decided that if he couldn’t travel physically, he would travel mentally. He asked me if I could find him a house of three hundred and sixty-five rooms so that he could live for a day and a night in each. In that way he thought life would seem almost interminable. The fact that he had probably not long to live had only heightened his passion to extend what was left of it. I told him that, short of the Royal Palace at Naples, I doubted whether such a house existed. Even the Palace in Rome probably contained fewer rooms.”

“He could have changed rooms less frequently in a smaller house.”

“He said that then he would notice the pattern. It would be no more than he was already accustomed to, travelling between Newmarket, Epsom, Goodwood and Brighton. He wanted time to forget the room which he had left before he returned to it again, and there must be opportunity too to redecorate it in a few essentials. You know there was a brothel in Paris in the Rue de Provence between the last two wars. (Oh, I forgot. There have been many wars since, haven’t there, but they don’t seem to belong to us like those two do.) This brothel had rooms decorated in various styles – the far West, China, India, that kind of thing. Your uncle had much the same idea for his house.”

“But surely he never found one,” I exclaimed.

“In the end he was forced to compromise. I was afraid for a time that the best we could do would be twelve bedrooms – one room a month – but a short while afterwards, through one of my clients in Milan…”

“I thought you were working in Venice,” I interrupted with some suspicion.

“The business I was in,” my aunt said, “was peripatetic. We moved around – a fortnight’s season in Venice, the same in Milan, Florence and Rome, then back to Venice. It was known as la quindicina.”

“You were in a theatre company?” I asked.

“The description will serve[71]”, my aunt said with that recurring ambiguity of hers. “You must remember I was very young in those days.”

“Acting needs no excuse.”

“I wasn’t excusing myself,” Aunt Augusta said sharply, “I was explaining. In a profession like that, age is a handicap. I was lucky enough to leave in good time. Thanks to Mr. Visconti.”

“Who was Visconti?”

“We were talking about your Uncle Jo. I found an old house in the country which had once been a palazzo or a castello[72] or something of the kind. It was almost in ruins and there were gypsies camping in some of the lower rooms and in the cellar – an enormous cellar which ran under the whole ground floor. It had been used for wine, and there was a great empty tun abandoned there because it had cracked with age. Once there had been vineyards around the house, but an autostrada had been built right across the estate not a hundred yards from the house, and the cars ran by all day between Milan and Rome and at night the big lorries passed. A few knotted worn-out roots of old vines were all that remained. There was only one bathroom in the whole house (the water had been cut off long ago by the failure of the electric pump), and only one lavatory, on the top floor in a sort of tower, but of course there was no water there either. You can imagine it wasn’t the sort of house anyone could sell easily – it had been on the market for twenty years[73] and the owner was a mongoloid orphan in an asylum. The lawyers talked about historic values, but Mr. Visconti knew all about history as you could guess from his name. Of course he advised strongly against the purchase, but after all poor Jo was unlikely to live long and he might as well be made happy. I had counted up the rooms, and if you divided the cellar into four with partitions and included the lavatory and bathroom and kitchen, you could bring the total up to fifty-two. When I told Jo he was delighted. A room for every week in the year, he said. I had to put a bed in every one, even in the bathroom and kitchen. There wasn’t room for a bed in the lavatory, but I bought a particularly comfortable chair with a footstool, and I thought we could always leave that room to the last – I didn’t think Jo would survive long enough to reach it. He had a nurse who was to follow him from room to room, sleeping one week behind him, as it were. I was afraid he would insist on a different nurse at every stopping place, but he liked her well enough to keep her as a travelling companion.”