полная версия

полная версияA Treatise on Domestic Economy; For the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School

Parents are little aware of the immense waste incurred by the present mode of conducting female education. In the wealthy classes, young girls are sent to school, as a matter of course, year after year, confined, for six hours a day, to the schoolhouse, and required to add some time out of school to learning their lessons. Thus, during the most critical period of life, they are for a long time immured in a room, filled with an atmosphere vitiated by many breaths, and are constantly kept under some sort of responsibility in regard to mental effort. Their studies are pursued at random, often changed with changing schools, while book after book (heavily taxing the parent's purse) is conned awhile, and then supplanted by others. Teachers have usually so many pupils, and such a variety of branches to teach, that little time can be afforded to each pupil; while scholars, at this thoughtless period of life, feeling sure of going to school as long as they please, manifest little interest in their pursuits.

The writer believes that the actual amount of education, permanently secured by most young ladies from the age of ten to fourteen, could all be acquired in one year, at the Institution described, by a young lady at the age of fifteen or sixteen.

Instead of such a course as the common one, if mothers would keep their daughters as their domestic assistants, until they are fourteen, requiring them to study one lesson, and go out, once a day, to recite it to a teacher, it would abundantly prepare them, after their constitutions are firmly established, to enter such an institution, where, in three years, they could secure more, than almost any young lady in the Country now gains by giving the whole of her youth to school pursuits.

In the early years of female life, reading, writing, needlework, drawing, and music, should alternate with domestic duties; and one hour a day, devoted to some study, in addition to the above pursuits, would be all that is needful to prepare them for a thorough education after growth is attained, and the constitution established. This is the time when young women would feel the value of an education, and pursue their studies with that maturity of mind, and vividness of interest, which would double the perpetuity and value of all their acquisitions.

The great difficulty, which opposes such a plan, is, the want of institutions that would enable a young lady to complete, in three years, the liberal course of study, here described. But if American mothers become convinced of the importance of such advantages for their daughters, and will use their influence appropriately and efficiently, they will certainly be furnished. There are other men of liberality and wealth, besides the individual referred to, who can be made to feel that a fortune, expended in securing an appropriate education to American women, is as wisely bestowed, as in founding colleges for the other sex, who are already so abundantly supplied. We ought to have institutions, similar to the one described, in every part of this Nation; and funds should be provided, for educating young women destitute of means: and if American women think and feel, that, by such a method, their own trials will be lightened, and their daughters will secure a healthful constitution and a thorough domestic and intellectual education, the appropriate expression of their wishes will secure the necessary funds. The tide of charity, which has been so long flowing from the female hand to provide a liberal education for young men, will flow back with abundant remuneration.

The last method suggested for lessening the evils peculiar to American women, is, a decided effort to oppose the aristocratic feeling, that labor is degrading; and to bring about the impression, that it is refined and lady-like to engage in domestic pursuits. In past ages, and in aristocratic countries, leisure and indolence and frivolous pursuits have been deemed lady-like and refined, because those classes, which were most refined, countenanced such an opinion. But whenever ladies of refinement, as a general custom, patronise domestic pursuits, then these employments will be deemed lady-like. It may be urged, however, that it is impossible for a woman who cooks, washes, and sweeps, to appear in the dress, or acquire the habits and manners, of a lady; that the drudgery of the kitchen is dirty work, and that no one can appear delicate and refined, while engaged in it. Now all this depends on circumstances. If a woman has a house, destitute of neat and convenient facilities; if she has no habits of order and system; if she is remiss and careless in person and dress;—then all this may be true. But, if a woman will make some sacrifices of costly ornaments in her parlor, in order to make her kitchen neat and tasteful; if she will sacrifice expensive dishes, in order to secure such conveniences for labor as protect from exposures; if she will take pains to have the dresses, in which she works, made of suitable materials, and in good taste; if she will rise early, and systematize and oversee the work of her family, so as to have it done thoroughly, neatly, and in the early part of the day; she will find no necessity for any such apprehensions. It is because such work has generally been done by vulgar people, and in a vulgar way, that we have such associations; and when ladies manage such things, as ladies should, then such associations will be removed. There are pursuits, deemed very refined and genteel, which involve quite as much exposure as kitchen employments. For example, to draw a large landscape, in colored crayons, would be deemed very lady-like; but the writer can testify, from sad experience, that no cooking, washing, sweeping, or any other domestic duty, ever left such deplorable traces on hands, face, and dress, as this same lady-like pursuit. Such things depend entirely on custom and associations; and every American woman, who values the institutions of her Country, and wishes to lend her influence in extending and perpetuating such blessings, may feel that she is doing this, whenever, by her example and influence, she destroys the aristocratic association, which would render domestic labor degrading.

CHAPTER IV.

ON DOMESTIC ECONOMY AS A BRANCH OF STUDY

The greatest impediment to making Domestic Economy a branch of study, is, the fact, that neither parents nor teachers realize the importance, or the practicability of constituting it a regular part of school education.

It is with reference to this, that the first aim of the writer will be, to point out some of the reasons for introducing Domestic Economy as a branch of female education, to be studied at school.

The first reason, is, that there is no period, in a young lady's life, when she will not find such knowledge useful to herself and to others. The state of domestic service, in this Country, is so precarious, that there is scarcely a family, in the free States, of whom it can be affirmed, that neither sickness, discontent, nor love of change, will deprive them of all their domestics, so that every female member of the family will be required to lend some aid, in providing food and the conveniences of living; and the better she is qualified to render it, the happier she will be, and the more she will contribute to the enjoyment of others.

A second reason, is, that every young lady, at the close of her schooldays, and even before they are closed, is liable to be placed in a situation, in which she will need to do, herself, or to teach others to do, all the various processes and duties detailed in this work. That this may be more fully realized, the writer will detail some instances, which have come under her own observation.

The eldest daughter of a family returned from school, on a visit, at sixteen years of age. Before her vacation had closed, her mother was laid in the grave; and such were her father's circumstances, that she was obliged to assume the cares and duties of her lost parent. The care of an infant, the management of young children, the superintendence of domestics, the charge of family expenses, the responsibility of entertaining company, and the many other cares of the family state, all at once came upon this young and inexperienced schoolgirl.

Again; a young lady went to reside with a married sister, in a distant State. While on this visit, the elder sister died, and there was no one but this young lady to fill the vacant place, and assume all the cares of the nursery, parlor, and kitchen.

Again; a pupil of the writer, at the end of her schooldays, married, and removed to the West. She was an entire novice in all domestic matters; an utter stranger in the place to which she removed. In a year, she became a mother, and her health failed; while, for most of the time, she had no domestics, at all, or only Irish or Germans, who scarcely knew even the names, or the uses, of many cooking utensils. She was treated with politeness by her neighbors, and wished to return their civilities; but how could this young and delicate creature, who had spent all her life at school, or in visiting and amusement, take care of her infant, attend to her cooking, washing, ironing, and baking, the concerns of her parlor, chambers, kitchen, and cellar, and yet visit and receive company? If there is any thing that would make a kindly heart ache, with sorrow and sympathy, it would be to see so young, so amiable, so helpless a martyr to the mistaken system of female education now prevalent. "I have the kindest of husbands," said the young wife, after her narrative of sufferings, "and I never regretted my marriage; but, since this babe was born, I have never had a single waking hour of freedom from anxiety and care. O! how little young girls know what is before them, when they enter married life!" Let the mother or teacher, whose eye may rest on these lines, ask herself, if there is no cause for fear that the young objects of her care may be thrown into similar emergencies, where they may need a kind of preparation, which as yet has been withheld.

Another reason for introducing such a subject, as a distinct branch of school education, is, that, as a general fact, young ladies will not be taught these things in any other way. In reply to the thousand-times-repeated remark, that girls must be taught their domestic duties by their mothers, at home, it may be inquired, in the first place, What proportion of mothers are qualified to teach a proper and complete system of Domestic Economy? When this is answered, it may be asked, What proportion of those who are qualified, have that sense of the importance of such instructions, and that energy and perseverance which would enable them actually to teach their daughters, in all the branches of Domestic Economy presented in this work?

It may then be asked, How many mothers actually do give their daughters instruction in the various branches of Domestic Economy? Is it not the case, that, owing to ill health, deficiency of domestics, and multiplied cares and perplexities, a large portion of the most intelligent mothers, and those, too, who most realize the importance of this instruction, actually cannot find the time, and have not the energy, necessary to properly perform the duty? They are taxed to the full amount of both their mental and physical energies, and cannot attempt any thing more. Almost every woman knows, that it is easier to do the work, herself, than it is to teach an awkward and careless novice; and the great majority of women, in this Country, are obliged to do almost every thing in the shortest and easiest way. This is one reason why the daughters of very energetic and accomplished housekeepers are often the most deficient in these respects; while the daughters of ignorant or inefficient mothers, driven to the exercise of their own energies, often become the most systematic and expert.

It may be objected, that such things cannot be taught by books. This position may fairly be questioned. Do not young ladies learn, from books, how to make hydrogen and oxygen? Do they not have pictures of furnaces, alembics, and the various utensils employed in cooking the chemical agents? Do they not study the various processes of mechanics, and learn to understand and to do many as difficult operations, as any that belong to housekeeping? All these things are explained, studied, and recited in classes, when every one knows that little practical use can ever be made of this knowledge. Why, then, should not that science and art, which a woman is to practise during her whole life, be studied and recited?

It may be urged, that, even if it is studied, it will soon be forgotten. And so will much of every thing studied at school. But why should that knowledge, most needful for daily comfort, most liable to be in demand, be the only study omitted, because it may be forgotten?

It may also be objected, that young ladies can get such books, and attend to them out of school. And so they can get books on Chemistry and Philosophy, and study them out of school; but will they do it? And why ought we not to make sure of the most necessary knowledge, and let the less needful be omitted? If young ladies study such a work as this, in school, they will remember a great part of it; and, when they forget, in any emergency, they will know where to resort for instruction. But if such books are not put into schools, probably not one in twenty will see or hear of them, especially in those retired places where they are most needed. And is it at all probable, that a branch, which is so lightly esteemed as to be deemed unworthy a place in the list of female studies, will be sought for and learned by young girls, who so seldom look into works of solid instruction after they leave school? So deeply is the writer impressed with the importance of this, as a branch of female education, at school, that she would deem it far safer and wiser to omit any other, rather than this.

Another reason, for introducing such a branch of study into female schools, is, the influence it would exert, in leading young ladies more correctly to estimate the importance and dignity of domestic knowledge. It is now often the case, that young ladies rather pride themselves on their ignorance of such subjects; and seem to imagine that it is vulgar and ungenteel to know how to work. This is one of the relics of an aristocratic state of society, which is fast passing away. Here, the tendency of every thing is to the equalisation of labor, so that all classes are feeling, more and more, that indolence is disreputable. And there are many mothers, among the best educated and most wealthy classes, who are bringing up their daughters, not only to know how to do, but actually to do, all kinds of domestic work. The writer knows young ladies, who are daughters of men of wealth and standing, and who are among the most accomplished in their sphere, who have for months been sent to work with a mantuamaker, to acquire a practical knowledge of her occupation, and who have at home learned to perform all kinds of domestic labor.

And let the young women of this Nation find, that Domestic Economy is placed, in schools, on equal or superior ground to Chemistry, Philosophy, and Mathematics, and they will blush to be found ignorant of its first principles, as much as they will to hesitate respecting the laws of gravity, or the composition of the atmosphere. But, as matters are now conducted, many young ladies know how to make oxygen and hydrogen, and to discuss questions of Philosophy or Political Economy, far better than they know how to make a bed and sweep a room properly; and they can "construct a diagram" in Geometry, with far more skill than they can make the simplest article of female dress.

It may be urged, that the plan suggested by the writer, in the previous pages, would make such a book as this needless; for young ladies would learn all these things at home, before they go to school. But it must be remembered, that the plan suggested cannot fully be carried into effect, till such endowed institutions, as the one described, are universally furnished. This probably will not be done, till at least one generation of young women are educated. It is only on the supposition that a young lady can, at fourteen or fifteen years of age, enter such an institution, and continue there three years, that it would be easy to induce her to remain, during all the previous period, at home, in the practice of Domestic Economy, and the limited course of study pointed out. In the present imperfect, desultory, varying, mode of female education, where studies are begun, changed, partially learned, and forgotten, it requires nearly all the years of a woman's youth, to acquire the intellectual education now demanded. While this state of things continues, the only remedy is, to introduce Domestic Economy as a study at school.

It is hoped that these considerations will have weight, not only with parents and teachers, but with young ladies themselves, and that all will unite their influence to introduce this, as a popular and universal branch of education, into every female school.

CHAPTER V.

ON THE CARE OF HEALTH

There is no point, where a woman is more liable to suffer from a want of knowledge and experience, than in reference to the health of a family committed to her care. Many a young lady, who never had any charge of the sick; who never took any care of an infant; who never obtained information on these subjects from books, or from the experience of others; in short, with little or no preparation; has found herself the principal attendant in dangerous sickness, the chief nurse of a feeble infant, and the responsible guardian of the health of a whole family.

The care, the fear, the perplexity, of a woman, suddenly called to these unwonted duties, none can realize, till they themselves feel it, or till they see some young and anxious novice first attempting to meet such responsibilities. To a woman of age and experience, these duties often involve a measure of trial and difficulty, at times deemed almost insupportable; how hard, then, must they press on the heart of the young and inexperienced!

There is no really efficacious mode of preparing a woman to take a rational care of the health of a family, except by communicating that knowledge, in regard to the construction of the body, and the laws of health, which is the basis of the medical profession. Not that a woman should undertake the minute and extensive investigation requisite for a physician; but she should gain a general knowledge of first principles, as a guide to her judgement in emergencies when she can rely on no other aid. Therefore, before attempting to give any specific directions on the subject of this chapter, a short sketch of the construction of the human frame will be given, with a notice of some of the general principles, on which specific rules in regard to health are based. This description will be arranged under the general heads of Bones, Muscles, Nerves, Blood-Vessels, Organs of Digestion and Respiration, and the Skin.

BONES

The bones are the most solid parts of the body. They are designed to protect and sustain it, and also to secure voluntary motion. They are about two hundred and fifty in number, (there being sometimes a few more or less,) and are fastened together by cartilage, or gristle, a substance like the bones, but softer, and more elastic.

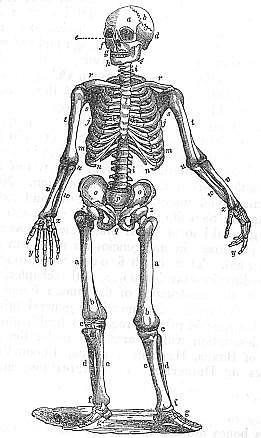

In order to convey a more clear and correct idea of the form, relative position, and connection, of the bones constituting the human framework, the engraving on page 70, (Fig. 1,) is given.

Fig. 1.

By the preceding engraving, it will be seen, that the cranium, or skull, consists of several distinct pieces, which are united by sutures, (or seams,) as represented by the zigzag lines; a, being the frontal bone; b, the parietal bone; c, the temporal bone; and d, the place of the occipital bone, which forms the back part of the head, and therefore is not seen in the engraving. The nasal bones, or bones of the nose, are shown at e; f, is the cheek bone; g, the upper, and h, the lower, jaw bones; i, i, the spinal column, or back bone, consisting of numerous small bones, called vertebræ; j, j, the seven true ribs, which are fastened to the spine, behind, and by the cartilages, k, k, to the sternum, or breast bone, l, in front; m, m, are the first three false ribs, which are so called, because they are not united directly to the breast bone, but by cartilages to the seventh true rib; n, n, are the lower two false, which are also called floating, ribs, because they are not connected with the breast bone, nor the other ribs, in front; o, o, p, q, are the bones of the pelvis, which is the foundation on which the spine rests; r, r, are the collar bones; s, s, the shoulder blades; t, t, the bones of the upper arm; u, u, the elbow joints, where the bones of the upper arm and fore arm are united in such a way that they can move like a hinge; v w, v w, are the bones of the fore arm; x, x, those of the wrists; y, y, those of the fingers; z, z, are the round heads of the thigh bones, where they are inserted into the sockets of the bones of the pelvis, giving motion in every direction, and forming the hip joint; a b, a b, are the thigh bones; c, c, the knee joints; d e, d e, the leg bones; f, f, the ankle joints; g, g, the bones of the foot.

The bones are composed of two substances,—one animal, and the other mineral. The animal part is a very fine network, called the cellular membrane. In this, are deposited the harder mineral substances, which are composed principally of carbonate and phosphate of lime. In very early life, the bones consist chiefly of the animal part, and are then soft and pliant. As the child advances in age, the bones grow harder, by the gradual deposition of the phosphate of lime, which is supplied by the food, and carried to the bones by the blood. In old age, the hardest material preponderates; making the bones more brittle than in earlier life.

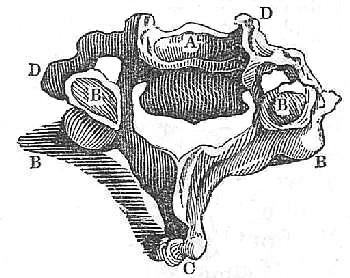

As we shall soon have occasion to refer, particularly, to the spinal, or vertebral column, and the derangement to which it is liable, we give, on page 72, representations of the different classes of vertebræ; viz. the cervical, (from the Latin, cervix, the neck,) the dorsal, (from dorsum, the back,) and lumbar, (from lumbus, the loins.)

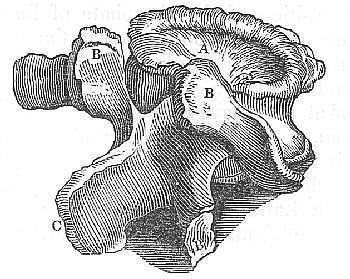

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2, represents one of the cervical vertebræ. Seven of these, placed one above another, constitute that part of the spine which is in the neck.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3, is one of the dorsal vertebræ, twelve of which, form the central part of the spine.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4, represents one of the lumbar vertebræ, (five in number,) which are immediately above the sacrum. These vertebræ are so fastened, that the spine can bend, in any direction; and the muscles of the trunk are used in holding it erect, or in varying its movements.

By the drawings here presented, it will be seen, that the vertebræ of the neck, back, and loins, differ somewhat in size and shape, although they all possess the same constituent parts; thus, A, in each, represents the body of the vertebræ; B, the articulating processes, by which each is joined to its fellow, above and below it; C, the spinous process, or that part of the vertebræ, which forms the ridge to be felt, on pressure, the whole length of the centre of the back. The back bone receives its name, spine, or spinal column, from these spinous processes.