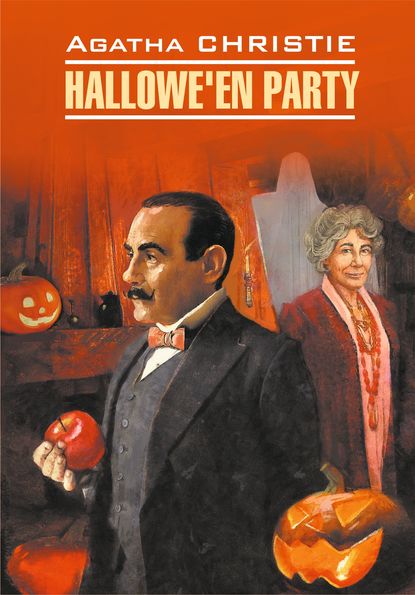

Полная версия

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz / Волшебник из страны Оз. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Simeon Lee said: ‘Quite right. You must stay here with us for a while.’

‘Oh, look here, sir. I can’t butt in like that[100]. It’s only two days to Christmas.’

‘You must spend Christmas with us – unless you’ve got other plans?’

‘Well, no, I haven’t, but I don’t like – ’

Simeon said: ‘That’s settled.’ He turned his head. ‘Pilar?’

‘Yes, Grandfather.’

‘Go and tell Lydia we shall have another guest. Ask her to come up here.’

Pilar left the room. Stephen’s eyes followed her. Simeon noted the fact with amusement. He said: ‘You’ve come straight here from South Africa?’

‘Pretty well.’

They began to talk of that country. Lydia entered a few minutes later.

Simeon said: ‘This is Stephen Farr, son of my old friend and partner, Ebenezer Farr. He’s going to be with us for Christmas if you can find room for him.’

Lydia smiled. ‘Of course.’ Her eyes took in the stranger’s appearance. His bronzed face and blue eyes and the easy backward tilt of his head.

‘My daughter-in-law,’ said Simeon.

Stephen said: ‘I feel rather embarrassed – butting in on a family party like this.’

‘You’re one of the family, my boy,’ said Simeon. ‘Think of yourself as that.’

‘You’re too kind, sir.’

Pilar re-entered the room. She sat down quietly by the fire and picked up the hand screen. She used it as a fan, slowly tilting her wrist to and fro. Her eyes were demure and downcast.

Part 3

December 24th

I

‘Do you really want me to stay on here, Father?’ asked Harry. He tilted his head back. ‘I’m stirring up rather a hornet’s nest[101], you know.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Simeon sharply.

‘Brother Alfred,’ said Harry. ‘Good brother Alfred! He, if I may say so, resents my presence here.’

‘The devil he does!’ snapped Simeon. ‘I’m master in this house.’

‘All the same, sir, I expect you’re pretty dependent on Alfred. I don’t want to upset – ’

‘You’ll do as I tell you,’ snapped his father.

Harry yawned. ‘Don’t know that I shall be able to stick a stay-at-home life. Pretty stifling to a fellow who’s knocked about the world[102].’

His father said: ‘You’d better marry and settle down.’

Harry said: ‘Who shall I marry? Pity one can’t marry one’s niece. Young Pilar is devilish attractive.’

‘You’ve noticed that?’

‘Talking of settling down, fat George has done well for himself as far as looks go[103]. Who was she?’

Simeon shrugged his shoulders. ‘How should I know? George picked her up at a mannequin parade, I believe. She says her father was a retired naval officer.’

Harry said: ‘Probably a second mate of a coasting steamer. George will have a bit of trouble with her if he’s not careful.’

‘George,’ said Simeon Lee, ‘is a fool.’

Harry said: ‘What did she marry him for – his money?’

Simeon shrugged his shoulders.

Harry said: ‘Well, you think that you can square Alfred all right?’

‘We’ll soon settle that,’ said Simeon grimly. He touched a bell that stood on a table near him. Horbury appeared promptly. Simeon said:

‘Ask Mr Alfred to come here.’

Horbury went out and Harry drawled: ‘That fellow listens at doors!’

Simeon shrugged his shoulders. ‘Probably.’

Alfred hurried in. His face twitched when he saw his brother. Ignoring Harry, he said pointedly: ‘You wanted me, Father?’

‘Yes, sit down. I was just thinking we must reorganize things a bit now that we have two more people living in the house.’

‘Two?’

‘Pilar will make her home here, naturally. And Harry is home for good[104].’

Alfred said: ‘Harry is coming to live here?’

‘Why not, old boy?’ said Harry.

Alfred turned sharply to him. ‘I should think that you yourself would see that[105]!’

‘Well, sorry – but I don’t.’

‘After everything that has happened? The disgraceful way you behaved. The scandal – ’

Harry waved an easy hand. ‘All that’s in the past, old boy.’

‘You behaved abominably to Father, after all he’s done for you.’

‘Look here, Alfred, it strikes me that’s Father’s business, not yours. If he’s willing to forgive and forget – ’

‘I’m willing,’ said Simeon. ‘Harry’s my son, after all, you know, Alfred.’

‘Yes, but – I resent it – for Father’s sake.’

Simeon said: ‘Harry’s coming here! I wish it.’ He laid a hand gently on the latter’s shoulder. ‘I’m very fond of Harry.’

Alfred got up and left the room. His face was white. Harry rose too and went after him, laughing.

Simeon sat chuckling to himself. Then he started and looked round. ‘Who the devil’s that? Oh, it’s you, Horbury. Don’t creep about[106] that way.’

‘I beg your pardon, sir.’

‘Never mind. Listen, I’ve got some orders for you. I want everybody to come up here after lunch – everybody.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘There’s something else. When they come, you come with them. And when you get half-way along the passage raise your voice so that I can hear. Any pretext will do. Understand?’

‘Yes, sir.’

Horbury went downstairs. He said to Tressilian: ‘If you ask me, we are going to have a Merry Christmas.’

Tressilian said sharply: ‘What d’you mean?’

‘You wait and see, Mr Tressilian. It’s Christmas Eve today, and a nice Christmas spirit abroad – I don’t think!’

II

They came into the room and paused at the doorway. Simeon was speaking into the telephone. He waved a hand to them. ‘Sit down, all of you. I shan’t be a minute.[107]’ He went on speaking into the telephone.

‘Is that Charlton, Hodgkins & Bruce? Is that you, Charlton? Simeon Lee speaking. Yes, isn’t it?… Yes… No, I wanted you to make a new will for me… Yes, it’s some time since I made the other… Circumstances have altered… Oh no, no hurry. Don’t want you to spoil your Christmas. Say Boxing Day[108] or the day after. Come along, and I’ll tell you what I want done. No, that’s quite all right. I shan’t be dying just yet.’

He replaced the receiver, then looked round at the eight members of his family. He cackled and said: ‘You’re all looking very glum. What is the matter?’

Alfred said: ‘You sent for us…’

Simeon said quickly: ‘Oh, sorry – nothing portentous about it. Did you think it was a family council? No, I’m just rather tired today, that’s all. None of you need come up after dinner. I shall go to bed. I want to be fresh for Christmas Day.’

He grinned at them. George said earnestly: ‘Of course… of course…’

Simeon said: ‘Grand old institution, Christmas. Promotes solidarity of family feeling. What do you think, Magdalene, my dear?’

Magdalene Lee jumped. Her rather silly little mouth flew open and then shut itself. She said: ‘Oh – oh, yes!’

Simeon said: ‘Let me see, you lived with a retired naval officer’ – he paused – ‘your father. Don’t suppose you made much of Christmas. It needs a big family for that!’

‘Well – well – yes, perhaps it does.’

Simeon’s eyes slid past her.

‘Don’t want to talk of anything unpleasant at this time of year, but you know, George, I’m afraid I’ll have to cut down your allowance a bit. My establishment here is going to cost me a bit more to run in future.’

George got very red. ‘But look here, Father, you can’t do that!’

Simeon said softly: ‘Oh, can’t I[109]!’

‘My expenses are very heavy already. Very heavy. As it is, I don’t know how I make both ends meet. It needs the most rigorous economy.’

‘Let your wife do a bit more of it,’ said Simeon. ‘Women are good at that sort of thing. They often think of economies where a man would never have dreamt of them. And a clever woman can make her own clothes. My wife, I remember, was clever with her needle. About all she was clever with – a good woman, but deadly dull – ’

David sprang up. His father said: ‘Sit down, boy, you’ll knock something over – ’

David said: ‘My mother – ’

Simeon said: ‘Your mother had the brains of a louse! And it seems to me she’s transmitted those brains to her children.’ He raised himself up suddenly. A red spot appeared on each cheek. His voice came high and shrill. ‘You’re not worth a penny piece, any of you! I’m sick of you all! You’re not men! You’re weaklings – a set of namby-pamby weaklings. Pilar’s worth any two of you put together! I’ll swear to heaven I’ve got a better son somewhere in the world than any of you, even if you are born the right side of the blanket[110]!’

‘Here, Father, hold hard,’ cried Harry.

He had jumped up and stood there, a frown on his usually good-humoured face. Simeon snapped: ‘The same goes for you! What have you ever done? Whined to me for money from all over the world! I tell you I’m sick of the sight of you all! Get out!’

He leaned back in his chair, panting a little.

Slowly, one by one, his family went out. George was red and indignant. Magdalene looked frightened. David was pale and quivering. Harry blustered out of the room. Alfred went like a man in a dream. Lydia followed him with her head held high. Only Hilda paused in the doorway and came slowly back.

She stood over him, and he started when he opened his eyes and found her standing there. There was something menacing in the solid way she stood there quite immovably.

He said irritably: ‘What is it?’

Hilda said: ‘When your letter came I believed what you said – that you wanted your family round you for Christmas, I persuaded David to come.’

Simeon said: ‘Well, what of it?’

Hilda said slowly: ‘You did want your family round you – but not for the purpose you said! You wanted them there, didn’t you, in order to set them all by the ears[111]? God help you, it’s your idea of fun!’

Simeon chuckled. He said: ‘I always had rather a specialized sense of humour. I don’t expect anyone else to appreciate the joke. I’m enjoying it!’

She said nothing. A vague feeling of apprehension came over Simeon Lee. He said sharply: ‘What are you thinking about?’

Hilda Lee said slowly: ‘I’m afraid…’

Simeon said: ‘You’re afraid – of me?’

Hilda said: ‘Not of you. I’m afraid – for you!’

Like a judge who has delivered sentence[112], she turned away. She marched, slowly and heavily, out of the room…

Simeon sat staring at the door. Then he got to his feet and made his way over to the safe. He murmured: ‘Let’s have a look at my beauties.’

III

The doorbell rang about a quarter to eight.

Tressilian went to answer it. He returned to his pantry to find Horbury there, picking up the coffee-cups off the tray and looking at the mark on them.

‘Who was it?’ said Horbury.

‘Superintendent of Police – Mr Sugden – mind what you’re doing![113]’

Horbury had dropped one of the cups with a crash.

‘Look at that now,’ lamented Tressilian. ‘Eleven years I’ve had the washing up of those and never one broken, and now you come along touching things you’ve no business to touch, and look what happens!’

‘I’m sorry, Mr Tressilian. I am indeed,’ the other apologized. His face was covered with perspiration. ‘I don’t know how it happened. Did you say a Superintendent of Police had called?’

‘Yes – Mr Sugden.’

The valet passed a tongue over pale lips.

‘What – what did he want?’

‘Collecting for the Police Orphanage.’

‘Oh!’ The valet straightened his shoulders. In a more natural voice he said: ‘Did he get anything?’

‘I took up the book to old Mr Lee, and he told me to fetch the superintendent up and to put the sherry on the table.’

‘Nothing but begging, this time of year,’ said Horbury. ‘The old devil’s generous, I will say that for him, in spite of his other failings.’

Tressilian said with dignity: ‘Mr Lee has always been an open-handed gentleman[114].’

Horbury nodded. ‘It’s the best thing about him! Well, I’ll be off now.’

‘Going to the pictures?’

‘I expect so. Ta-ta, Mr Tressilian.’ He went through the door that led to the servants’ hall.

Tressilian looked up at the clock hanging on the wall. He went into the dining-room and laid the rolls in the napkins. Then, after assuring himself that everything was as it should be, he sounded the gong in the hall.

As the last note died away the police superintendent came down the stairs. Superintendent Sugden was a large handsome man. He wore a tightly buttoned blue suit and moved with a sense of his own importance.

He said affably: ‘I rather think we shall have a frost tonight. Good thing: the weather’s been very unseasonable lately.’

Tressilian said, shaking his head: ‘The damp affects my rheumatism.’

The superintendent said that the rheumatism was a painful complaint, and Tressilian let him out by the front door.

The old butler refastened the door and came back slowly into the hall. He passed his hand over his eyes and sighed. Then he straightened his back as he saw Lydia pass into the drawing-room. George Lee was just coming down the stairs.

Tressilian hovered ready. When the last guest, Magdalene, had entered the drawing-room, he made his own appearance, murmuring: ‘Dinner is served.’

In his way Tressilian was a connoisseur of ladies’ dress. He always noted and criticized the gowns of the ladies as he circled round the table, decanter in hand.

Mrs Alfred, he noted, had got on her new flowered black and white taffeta. A bold design, very striking, but she could carry it off, though many ladies couldn’t. The dress Mrs George had on was a model, he was pretty sure of that. Must have cost a pretty penny.[115] He wondered how Mr George would like paying for it! Mr George didn’t like spending money – he never had. Mrs David now: a nice lady, but didn’t have any idea of how to dress. For her figure, plain black velvet would have been the best. Figured velvet[116], and crimson at that, was a bad choice. Miss Pilar, now, it didn’t matter what she wore, with her figure and her hair she looked well in anything. A flimsy cheap little white gown it was, though. Still, Mr Lee would soon see to that! Taken to her wonderful[117], he had. Always was the same way when a gentleman was elderly. A young face could do anything with him!

‘Hock or claret?’ murmured Tressilian in a deferential whisper in Mrs George’s ear. Out of the tail of his eye[118] he noted that Walter, the footman, was handing the vegetables before the gravy again – after all he had been told!

Tressilian went round with the soufflé. It struck him, now that his interest in the ladies’ toilettes and his misgivings over Walter’s deficiencies were a thing of the past, that everyone was very silent tonight. At least, not exactly silent: Mr Harry was talking enough for twenty – no, not Mr Harry, the South African gentleman. And the others were talking too, but only, as it were, in spasms. There was something a little – queer about them.

Mr Alfred, for instance, he looked downright ill. As though he had had a shock or something. Quite dazed he looked and just turning over the food on his plate without eating it. The mistress, she was worried about him. Tressilian could see that. Kept looking down the table towards him – not noticeably, of course, just quietly. Mr George was very red in the face – gobbling his food, he was, without tasting it. He’d get a stroke one day if he wasn’t careful. Mrs George wasn’t eating. Slimming, as likely as not.[119] Miss Pilar seemed to be enjoying her food all right and talking and laughing up at the South African gentleman. Properly taken with her, he was. Didn’t seem to be anything on their minds!

Mr David? Tressilian felt worried about Mr David. Just like his mother he was, to look at. And remarkably young-looking still. But nervy; there, he’d knocked over his glass.

Tressilian whisked it away, mopped up the stream deftly. It was all over. Mr David hardly seemed to notice what he had done, just sat staring in front of him with a white face.

Thinking of white faces, funny the way Horbury had looked in the pantry just now when he’d heard a police officer had come to the house… almost as though —

Tressilian’s mind stopped with a jerk. Walter had dropped a pear off the dish he was handing. Footmen were no good nowadays! They might be stable-boys[120], the way they went on!

He went round with the port. Mr Harry seemed a bit distrait tonight. Kept looking at Mr Alfred. Never had been any love lost between those two[121], not even as boys. Mr Harry, of course, had always been his father’s favourite, and that had rankled with Mr Alfred. Mr Lee had never cared for Mr Alfred much. A pity, when Mr Alfred always seemed so devoted to his father.

There, Mrs Alfred was getting up now. She swept round the table. Very nice that design on the taffeta; that cape suited her. A very graceful lady.

He went out to the pantry, closing the dining-room door on the gentlemen with their port.

He took the coffee tray into the drawing-room. The four ladies were sitting there rather uncomfortably, he thought. They were not talking. He handed round the coffee in silence.

He went out again. As he went into his pantry he heard the dining-room door open. David Lee came out and went along the hall to the drawing-room.

Tressilian went back into his pantry. He read the riot act[122] to Walter. Walter was nearly, if not quite, impertinent! Tressilian, alone in his pantry, sat down rather wearily. He had a feeling of depression. Christmas Eve, and all this strain and tension… He didn’t like it!

With an effort he roused himself. He went to the drawing-room and collected the coffee-cups. The room was empty except for Lydia, who was standing half-concealed by the window curtain at the far end of the room. She was standing there looking out into the night.

From next door the piano sounded. Mr David was playing. But why, Tressilian asked himself, did Mr David play the Dead March? For that’s what it was. Oh, indeed things were very wrong[123].

He went slowly along the hall and back into his pantry. It was then he first heard the noise from overhead: a crashing of china, the overthrowing of furniture, a series of cracks and bumps.

‘Good gracious!’ thought Tressilian. ‘Whatever is the master doing? What’s happening up there?’

And then, clear and high, came a scream – a horrible high wailing scream that died away in a choke or gurgle.

Tressilian stood there a moment paralysed, then he ran out into the hall and up the broad staircase. Others were with him. That scream had been heard all over the house.

They raced up the stairs and round the bend, past a recess with statues gleaming white and eerie, and along the straight passage to Simeon Lee’s door. Mr Farr was there already and Mrs David. She was leaning back against the wall and he was twisting at the door handle.

‘The door’s locked,’ he was saying. ‘The door’s locked!’

Harry Lee pushed past and wrested it from him. He, too, turned and twisted at the handle. ‘Father,’ he shouted. ‘Father, let us in.’

He held up his hand and in the silence they all listened. There was no answer. No sound from inside the room.

The front door bell rang, but no one paid any attention to it.

Stephen Farr said: ‘We’ve got to break the door down. It’s the only way.’

Harry said: ‘That’s going to be a tough job. These doors are good solid stuff. Come on, Alfred.’

They heaved and strained. Finally they went and got an oak bench and used it as a battering-ram. The door gave at last. Its hinges splintered and the door sank shuddering from its frame.

For a minute they stood there huddled together looking in. What they saw was a sight that no one of them ever forgot…

There had clearly been a terrific struggle. Heavy furniture was overturned. China vases lay splintered on the floor. In the middle of the hearthrug in front of the blazing fire lay Simeon Lee in a great pool of blood… Blood was splashed all round. The place was like a shambles.

There was a long shuddering sigh, and then two voices spoke in turn. Strangely enough, the words they uttered were both quotations.

David Lee said: ‘The mills of God grind slowly[124]…’

Lydia’s voice came like a fluttering whisper: ‘Who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?[125]…’

IV

Superintendent Sugden had rung the bell three times. Finally, in desperation, he pounded on the knocker.

A scared Walter at length opened the door. ‘Oo-er,’ he said. A look of relief came over his face. ‘I was just ringing up the police.’

‘What for?’ said Superintendent Sugden sharply. ‘What’s going on here?’

Walter whispered: ‘It’s old Mr Lee. He’s been done in[126]… ’

The superintendent pushed past him and ran up the stairs. He came into the room without anyone being aware of his entrance[127]. As he entered he saw Pilar bend forward and pick up something from the floor. He saw David Lee standing with his hands over his eyes.

He saw the others huddled into a little group. Alfred Lee alone had stepped near his father’s body. He stood now quite close, looking down. His face was blank[128].

George Lee was saying importantly:

‘Nothing must be touched – remember that – nothing – till the police arrive. That is most important!’

‘Excuse me,’ said Sugden. He pushed his way forward, gently thrusting the ladies aside. Alfred Lee recognized him.

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘It’s you, Superintendent Sugden. You’ve got here very quickly.’

‘Yes, Mr Lee.’ Superintendent Sugden did not waste time on explanations. ‘What’s all this?’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

I wish I hadn’t come… – (разг.) Лучше бы я не возвращался

2

Is it worth it? – (разг.) А стоит ли?

3

the smell of the bull-ring – (зд.) запах корриды

4

was prepared for every eventuality – (уст.) была готова к любой неожиданности

5

they were not at all gay – (разг.) они были вовсе не веселыми

6

as a matter of course – (разг.) как и следовало ожидать

7

Wild West films – (уст.) вестерны

8

in a body – (разг.) одновременно; все вместе

9

she had no rigid taboos – (разг.) у нее не было строгих запретов на что бы то ни было

10

might have felt ill at ease – (разг.) мог почувствовать себя неловко

11

General Franco – генерал Франко Баамонде (1892–1975), глава испанского государства, вождь Испанской фаланги, в 1936 г. возглавил военно-фашистский мятеж против Испанской республики

12

It was a nuisance – (разг.) Это было досадно

13

I wonder – (разг.) Вот и мне интересно; мне и самому хотелось бы знать

14

in the midst of some sober British family – (разг.) среди рассудительного и спокойного британского семейства

15

give in to him – (разг.) уступать ему; подчиняться

16

to have his own way – (разг.) всегда добиваться своего; стоять на своем

17

some time or other – (разг.) хотя бы изредка

18

it is always liable to be upset – (разг.) всегда есть вероятность, что планы будут нарушены

19

never grudges us money – (разг.) не ограничивает нас в тратах