полная версия

полная версияJohn Bull, Junior: or, French as She is Traduced

"No, sir, I don't think I do."

"Do you know any mathematics?"

"Do you mean arithmetic, sir?"

"Yes, I do."

"Please, sir, I can do addition, subtraction, multiplication, and short division."

"I suppose you will try the English subjects. Do you know any English?"

"Yes, sir, I can speak English," he said, looking at me with surprise.

"Of course you can," I replied; "but you know some history, I suppose. Have you ever read any English history?"

"Yes, sir, I have read 'Robinson Crusoe.'"

"Well, well, my poor boy, I am afraid you have not much chance of getting a scholarship."

"Haven't I?" said the dear child, and he burst into tears. Then he handed me a letter, which was addressed to the head-master.

It was a supplication from his mother. Her little boy was very clever, she said, and she hoped he would not be judged by what he actually knew, but by what she was sure he would be able to learn if admitted into the school.

Poor child! we comforted him as well as we could, and sent him back to his mamma. He was very miserable.

Ladies are sometimes great at testimonials, and they must think it very ungentlemanly of men not to favor their candidates.

When our head science mastership was vacant, over a hundred applications were lodged with the head-master for his consideration. I remember that among the candidates there was one who was only provided with a single testimonial, and this from a lady (an old lady, I imagine). The testimonial was to the effect that "she had known Mr. P. for many years. He was a good and steady young man, and she knew he was very fond of science."

This testimonial failed to secure the appointment for its owner.

XVII

The Origin of Anglomania and Anglophobia in England. – A Typical Frenchman. – Too Much of an Englishman. – A Remarkable French Master. – John Bull made to go to Church by a Frenchman. – A Noble and Thankless Career. – A Place of Learning. – Mons. and Esquire. – All Ladies and Gentlemen. – One Exception. – Wonderful Addresses.

The French in England are of two sorts, those who, by their intelligence, industry, and perseverance, have succeeded in building up an honorable position for themselves, and those who, by the lack of these qualities, vegetate there as they would be pretty sure to do anywhere.

The former do not all love the land of their adoption, but they all respect it. The latter, unwilling to lay their poverty at their own door, throw the blame upon England for not having understood them, and they have not a good word to say for her. It never occurred to them that it was theirs to study and understand England, and that England is not to be blamed for not having studied them and changed her ways to accommodate them.

They never part with a shilling without remarking that for a penny they would be able to obtain the same value in France. You often wonder how it is they stick to this country instead of honoring their own with their presence.

I have always been an admirer of that worthy Frenchman who carries his patriotism to the extent of buying all his clothing in France. He declares it impossible to wear English garments, and almost impossible to wear out French ones. Besides, he does not see why he should not give his country the benefit of some of the guineas he has picked up over here. Like every child of France, he has the love of good linen, and according to him the article is only to be found in Paris.

So he goes about in his narrow-brimmed hat, and turned-down collar fastened low in the neck, and finished off with a tiny black tie, a large expanse of shirt-front, and boots with high heels and pointed toes. As he goes along the street, he hears people whisper: "There's a Frenchman!" But, far from objecting to that, he rather likes it, and he is right.

He speaks bad English, and assures you that you require very few words to make yourself understood of the people. He does not go so far as Figaro, but his English vocabulary is of the most limited.

Without making any noise about it, he sends his guinea to all the French Benevolent Societies in England, and wherever the tricolor floats he is of the party.

He likes the English, and recognizes their solid qualities; but as he possesses many of his own, he keeps to his native stock.

How this good Frenchman does shine by the side of another type, a type which, I am happy to say, is rare – the one who drops his country.

The latter, when he speaks of England, says: "We do this, we do that, in England," not "The English do this, the English do that." He would like to say, "We English," but he hardly dares go that length.

He dresses à l'anglaise with a vengeance, makes it a point to frequent only English houses, and spends a good deal of his time in running down his compatriots.

He does not belong to any of the French societies or clubs in England. These establishments, however, do not miss him much more than his own country.

I once knew one of this category. His name ended with an e mute preceded by a double consonant. The e mute was a real sore to him, the grief of his life. Without it he might have passed for English. It was too provoking to be thus balked, and, as he signed his name, he would dissimulate the poor offending little vowel, so that his name should appear to end at the double consonant.

He was not a genius.

Acting under the theory of Figaro, "Qu'il n'est pas nécessaire de tenir les choses pour en raisonner," I have heard an Englishman, engaged in teaching French, maintain that it was not necessary to be able to speak the French language to teach it.

On the other hand, I once heard an eminent Frenchman hold that the less English a French master knew the more fit he was to teach French.

Both gentlemen begged their audience to understand that they made their statements on their own sole responsibility.

I never met a French master who had made his fortune, nor have you, I imagine.

I once met in England a French master who had not written a French grammar.

I was one day introduced to a Frenchman who keeps a successful school in the Midland counties. He makes it a rule to sternly refuse to let his boys go home in the neighboring town before one o'clock on Sundays. When parents ask him as a special favor to allow their sons to come to their house on Saturday night or early on Sunday morning, he answers: "I am sorry I cannot comply with your request. It has come to my knowledge that there are parents who do not insist on their children going to church, and I cannot allow any of my pupils to go home before they have attended divine service."

John Bull made to go to church by a Frenchman! The idea was novel, and I thought extremely funny.

To teach "the art of speaking and writing the French language correctly" is a noble but thankless career in England.

In France, the Government grants a pension to, and even confers the Legion of Honor upon, an English master13 after he has taught his language in a lycée for a certain number of years.

The Frenchman who has taught French in England all his lifetime is allowed, when he is done for, to apply at the French Benevolent Society for a free passage to France, where he may go and die quietly out of sight.

If you look at the advertisements published daily in the "educational" columns of the papers, you may see that compatriots of mine give private lessons in French at a shilling an hour, and teach the whole language in 24 or 26 lessons. Why not 25? I always thought there must be something cabalistic about the number 26. These gentlemen have to wear black coats and chimney-pots. How can they do it if their wives do not take in mangling?

Mystery.

In a southern suburb of London, I remember seeing a little house covered, like a booth at a fair, with boards and announcements that spoke to the passer-by of all the wonders to be found within.

On the front-door there was a plate with the inscription:

"Mons. D., of the University of France."Now Englishmen who address Frenchmen as "Mons."14 should be forgiven. They unsuccessfully aim at doing a correct thing. But a Frenchman dubbing himself "Mons." publishes a certificate of his ignorance.

The house was a double-fronted one.

On the right window there was the inscription:

"French Classes for Ladies."On the left one:

"French Classes for Gentlemen."The sexes were separated as at the Turkish Baths.

On a huge board, placed over the front door, I read the following:

"French Classes for Ladies and Gentlemen.

Greek, Latin, and Mathematical Classes.

Art and Science Department.

Music, Singing, and Dancing taught.

Private Lessons given, Families waited upon.

Schools attended.

For Terms and Curriculum, apply within."

What a saving of trouble and expense it would have been to this living encyclopædia if he had only mentioned what he did not teach!

Since I have called your attention to the expression Mons., and reminded you of its proper meaning, never send a letter to a Frenchman with the envelope addressed as Mons.

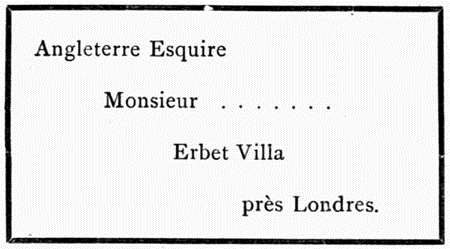

I know, dear American reader, that you never do. But you have friends. Well, tell them to write Monsieur in full; or, as cobblers in their back parlors are now addressed as Esquires, rather confer the same honor upon a Frenchman. He will take it as a compliment.

Democracy is making progress in England. Where is the time when only land-owners, barristers, graduates of the Universities, were addressed as Esquires?

All ladies and gentlemen in England now.

Not all, though.

A young lady friend, who visits the poor in her district, called one day at a humble dwelling.

She knocked at the door, and on a woman opening it, asked to see Mrs. – .

"Oh! very well," said the woman, and, leaving the young lady in the street, she went inside, and called out at the top of her voice:

"Ada, tell the lady on the second floor that a young person from the district wants to see her."

Apropos of "Esquire" I should like to take the opportunity of paying a well-deserved compliment to the Postal Authorities in England.

Some eight years ago, I lived in the Herbert Road, Shooter's Hill, near London.

After three weeks of wonderful peregrinations, a letter, addressed in the following manner, duly reached me from France:

My dear compatriot had heard that "Esquire" had to be put somewhere, or else the letter would not reach me.

This is not the only letter addressed to me calculated to puzzle the postman.

A letter was once brought to me with the following high-flown inscription:

"Al gentilissimo cavaliere professore

Signor…"

But what is even this, compared to the one I received from a worthy Bulgarian, and which was addressed to

"Monsieur…

Métropolitain de Saint Paul."

I was at the time teaching under the shadow of London's great cathedral.

XVIII

The Way to Learn Modern Languages.

I have always felt a great deal of sympathy, and even respect, for that good, honest, straight-forward young British boy who does not easily understand that in French "a musical friend" is not necessarily un ami à musique, nor "to sit on the committee," s'asseoir sur le comité, unless the context indicates that it is the painful operation which is meant. Poor boy! For him a foreign language is only his own, with another vocabulary; and so, when he does a piece of translation, he carefully replaces on his paper each word of his English text by one of the equivalents that he finds for it in his dictionary, rarely failing to choose the wrong one, as I have already said. Now comes que. Shall he put the subjunctive or the indicative? He has learnt his grammar: he could, if occasion required, recite the rules that apply to the employment of the terrible subjunctive mood. He has even, once or twice in his life, written an exercise on the subject, and as it was headed "Exercise on the Subjunctive Mood," he went through it with calm confidence, putting all the verbs in the subjunctive, including those that it would have been advisable to put in the indicative. This done, he was not supposed to commit any more mistakes on this important point of grammar. He might as well be expected to be an experienced swimmer after once reading Captain Webb's "Art of Swimming," and going through the various evolutions indicated in the pamphlet, à sec on the floor of his papa's parlor.

I admit that the French teacher of a public school ought to be a good philologist to make his lessons attractive to the students of the upper forms, and insure their success under examination; I admit that he should know English thoroughly, to be able to explain to them the delicacies of the French language, and maintain good discipline in his classes; I admit that he should be able to teach grammar, philology, history, literature; but I maintain that he ought never to lose sight of the most important object of the study of a living language, – the putting of it into practice; he should, above all things, and by all means, aim at making his pupils speak French. It is not enough that he should speak to them in French, even in the upper forms, where he would be perfectly understood: understanding a language and speaking it are two very different things. Neither will he attain his end by means of dull manuals of imaginary conversations with the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick-maker; these will, at most, be useful in helping a foreigner to ask for what he wants at a table d'hôte. You will not get grown-up, intelligent, and well-educated boys to come out of their shells, unless you make it worth their while. Now, Englishmen, like Americans, love argument, very often for argument's sake, and every school-boy, in England as in America, is a member of some society or committee, and at its meetings tries his wings, discusses, harangues, and prepares himself for that great parliamentary life, which is the strength of the nation.

Then, I ask, why not turn this love of discussion to account?

Start a French debating society in every school, and you will teach your generation to speak French. Such a proposition may sound bold, but it has been tried in several public schools, and has proved a complete success.

What cannot a teacher do that has succeeded in winning the esteem and affection of his pupils? First, make them respect you, then gain their hearts, and you will lead the young by a thread.

Take twenty or thirty boys, old enough to appreciate the interest you feel in them, and say to them, "My young friends, let us arrange to meet once a week, and see if we cannot speak French together. We will chat about any thing you like: politics even. Do not be afraid to open your lips, it is only la première phrase qui coûte. I am neither a Pecksniff nor a pedant, a dotard nor a wet blanket; in your company, I feel as young as the youngest among you. Do not imagine that I shall bring you up for the slightest error of pronunciation you make. I remember the time when I murdered your language, and I should be sorry to cast the first stone at you. At first I shall only correct your glaring mistakes; by degrees, you will make fewer and fewer, although, alas! you will very likely always make some. What does it matter? I guarantee that in a few months you will be able to understand all that is said to you in French, and express intelligibly in the same language any idea that may pass through your brain."

These little French parliaments work admirably; the earliest were started in two or three English schools four or five years ago. Each has its president – the head French teacher of the school, its honorary and assistant secretaries, and, if you please, its treasurer, who supplies the members with two or three good French papers, and, when the finances of the society permit, provides the means of giving a soirée littéraire. I have seen the minute-book of one of these interesting associations. Since its formation, this particular debating society has altered the whole map of Europe, greatly to the advantage of the United Kingdom. The young debaters have upset any number of governments, at home and abroad, done away with women's rights, and declared, by a crushing majority, that ladies who can make good puddings are far more useful members of society than those who can make good speeches. Young British boys have very strong sentiments against women's rights. In literature, the respective merits of the Classicists and the Romanticists have been discussed, and the "three unities" declared absurd and tyrannical by these young champions of freedom.

The speakers are not allowed to read their speeches, but may use notes for reference, and I notice that speakers, who at first only ventured short remarks, soon grew bold enough to hold forth for ten minutes at a time. In many instances, the president has had to adjourn a debate to the next meeting, on account of the number of orators wishing to take part in it. These minutes, written in very good French indeed, do great credit to the young secretary who enters them. I have myself been present at meetings of these societies, and I assure you that if you could see these young fellows rise from their seats, and, bowing respectfully to the president, say to him: "Monsieur le Président, je demande la parole," you would agree with me that, so far as good order, perfect courtesy, and unlimited respect for opposite views are concerned, these small gatherings would compare favorably with the meetings of honorables and even right-honorables that are held at the Capitol, the Westminster Palace, and the Palais Bourbon.

It is clear to my mind that, by such means, English boys can be made to speak French in the most interesting manner, and the one best suited to their taste. I firmly believe that if the great schools, public or private, were to start similar societies, that if all the young men knowing a little French were to form in their districts, such associations under the leadership of able and cheerful Frenchmen, England, or America for that matter, would in a few years, have a generation of French-speaking men.

I have always been at a loss to understand how boys who have been studying a language for nine or ten years should leave school perfectly unable to converse intelligibly in that language for five minutes together. It seems nothing short of scandalous.

Yet the reason is not far to be found. In England, at any rate, modern languages are taught like dead languages: they are taught through the eyes, whereas they should be taught through the ears and mouth.

The French debating society seems to me the best mode of solving the difficulty. I have often given this piece of advice to John Bull, and I myself founded a successful French debating society in England. Let Jonathan forgive my presumption if I avail myself of his kind and generous hospitality to give him the same advice.

XIX

English and French Schoolboys. – Their Characteristics. – The Qualities of the English School-boy. – What is Required of a Master to Win.

I have often been asked the question, "Are English boys better or worse than French ones?"

Well, I believe the genus boy to be pretty much the same all the world over. Their characteristics do not show in the same way, because educational systems are different.

Both English and French boys are particularly keen in finding out the peculiarities of a master, and taking his measure.

They are both inclined to bestow their affection and respect on the man who is possessed of moral and intellectual power; it is in their nature to love and respect what is powerful, lofty, and good.

Boys are what masters make them.

Both English and French boys are lazy if you give them a chance; both are industrious if you give them inducements to work. They will not come out of their shells unless you make it worth their while.

Both are as fond of holidays as any school-master alive.

French boys are more united among themselves, because their life would be intolerable if close friendship did not spring up between them, and help them to endure a secluded time of hardship and privations.

English boys are prouder, because they are freer. Their pride is born of liberty itself.

The former work more, the latter play more.

But comparisons are odious, especially when made between characters studied under such different circumstances.

What I can affirm is that a Frenchman need not fear that English boys (such as I have known at any rate) will take advantage of his shortcomings as regards his pronunciation of the English language to make his life uncomfortable. I have always found English boys charitable and generous.

A Frenchman will experience no difficulty in getting on with English schoolboys if his character wins their respect, and his kindness their affection; if he sympathizes with them in their difficulties; if he deals with them firmly, but always in a spirit of fair play, truth, and justice; if he is

"To their faults a little blind,And to their virtues very kind."THE END1

Things have changed in England since the dynamite scare.

2

"The Old Curiosity Shop."

3

Here I have to make a painful confession. I have actually acceded to a request from my American publishers, men wholly destitute of humor, to supply the reader with a translation of the few French sentences used in this little volume. This monument of my weakness will be found at the end.

4

Poor little chap!

5

Being a little bit of a philologist, I assume this verb comes from the common (very common) noun, 'Arry.

6

A street in London where Jews sell second-hand books.

7

I reproduce the note which had "helped" the boy:

["Renaud dans les jardins d'Armida," the enchanted gardens of Armida ("Jerusalem Delivered," Tasso), figuratively, in the hands of an enchantress.]

8

Dear boy! he probably was a weekly boarder, and the Sunday fare at home had left sweet recollections in his mind. This beats Swift's etymology of "cucumber," which he once gave at a dinner of the Philological Society: "King Jeremiah, Jeremiah King, Jerkin, Gherkin, Cucumber."

9

"'Cheval' comes from 'equus' no doubt; but it must be confessed that, to come to us in that state, it has sadly altered on the way."