полная версия

полная версияJohn Bull, Junior: or, French as She is Traduced

"Perhaps the mice ate it!" you are wicked enough to suggest.

This makes him smile and blush. He generally collapses before a remark like this.

But if he has a good excuse, behold him!

"I could not do my exercise last night," said to me one day a young Briton. It was evident from his self-satisfied and confident assurance that he had a good answer ready for my inquiry.

"You couldn't," I said; "why?"

"Please, sir, grandmamma died last night!"

"Oh! did she? Well, well – I hope this won't happen again."

This put me in mind of the boy who, being reproached for his many mistakes in his translation, pleaded:

"Please, sir, it isn't my fault. Papa will help me."

An English schoolboy never tells stories – never.

A mother once brought her little son to the head-master of a great public school.

"I trust my son will do honor to the school," she said; "he is a good, industrious, clever, and trustworthy boy. He never told a story in his life."

"Oh! madam, boys never do," replied the head-master.

The lady left, somewhat indignant. Did the remark amount to her statement being disbelieved, or to an affirmation that her boy was no better than other boys?

Of course every mother is apt to think that her Johnny or Jenny is nature's highest utterance. But for blind, unreasoning adoration, commend me to a fond grandmamma.

The first time I took my child on a visit to my mother in dear old Brittany, grandmamma received compliments enough on the subject of the "lovely petite blonde" to turn her head. But it did not want much turning, I must say. One afternoon, my wife was sitting with Miss Baby on her lap, and grandmamma, after devouring the child with her eyes for a few moments, said to us:

"You are two very sensible parents. Some people are so absurd about their babies! Take Madame T., for instance. She was here this morning, and really, to hear her talk, one would think that child of hers was an angel of beauty – that there never was such another."

"Well, but, grandmamma," said my wife, "you know yourself that you are forever discoursing of the matchless charms of our baby to your friends."

"Ah!" cried the dear old lady, as serious as a judge; "but that's quite different; in our case it's all true."

If you ever hope to find the British schoolboy at fault, your life will be a series of disappointments. Judge for yourself.

I (once): "Well, Brown, you bring no exercise this morning. How is that?"

Promising Briton: "Please, sir, you said yesterday that we were to do the 17th exercise."

I (inquiringly): "Well?"

P. B. (looking sad): "Please, sir, Jones said to me, last night, that it was the 18th exercise we were to do."

I (surprised): "But, my dear boy, you do not bring me any exercise at all."

P. B. (looking good): "Please, sir, I was afraid to do the wrong one."

Dear, dear child! the thought of doing wrong but once was too much for him! I shall always have it heavy on my conscience to have rewarded this boy's love of what is right by calling upon him to write out each of those exercises five times.

That thick-necked boy, whom you see there on the front row aiming at looking very good, and whom his schoolfellows are wicked and disrespectful enough to surname "Potted Angel," is sad and sour. His eyes are half open, his tongue seems to fill his mouth, and to speak, or rather to jerk out the words, he has to let it hang out. His mouth moves sideways like that of a ruminant; you would imagine he was masticating a piece of tough steak. He blushes, and never looks at you, except on the sly, with an uncomfortable grin, when your head is turned away. It seems to give him pain to swallow, and you would think he was suffering from some internal complaint.

This, perhaps, can be explained. The conscience lies just over the stomach, if I am to trust boys when they say they put their hands on their conscience. Let this conscience be heavily loaded, and there you have the explanation of the grumbling ailment that disturbs the boy in the lower regions of his anatomy.

To be good is all right, but you must not over-do it. This boy is beyond competition, a standing reproach, an insult to the rest of the class.

You are sorry to hear, on asking him what he intends to be, that he means to be a missionary. His face alone will be worth £500 a year in the profession. Thinking that I have prepared this worthy for missionary work, I feel, when asked what I think of missionaries, like the jam-maker's little boy who is offered jam and declines, pleading:

"No, thanks – we makes it."

I have great respect for missionaries, but I have always strongly objected to boys who make up their minds to be missionaries before they are twelve years old.

Some good, straightforward boys are wholly destitute of humor. One of them had once to put into French the following sentence of Charles Dickens: "Mr. Squeers had but one eye, and the popular prejudice runs in favor of two." He said he could not put this phrase into French, because he did not know what it meant in English.

"Surely, sir," he said to me, "it is not a prejudice to prefer two eyes to one."

This boy was wonderfully good at facts, and his want of humor did not prevent him from coming out of Cambridge senior classic, after successfully taking his B.A. and M.A. in the University of London.

This young man, I hear, is also going to be a missionary. The news goes far to reconcile me to the noble army of John Bull's colonizing agents, but I doubt whether the heathen will ever get much entertainment out of him.

Some boys can grasp grammatical facts and succeed in writing a decent piece of French; but, through want of literary perception, they will give you a sentence that will make you feel proud of them until you reach the end, when, bang! the last word will have the effect of a terrible bump on your nose.

A boy of this category had to translate this other sentence of Dickens:2 "She went back to her own room, and tried to prepare herself for bed. But who could sleep? Sleep!"3

His translation ran thus: "Elle se retira dans sa chambre, et fit ses préparatifs pour se coucher. Mais qui aurait pu dormir? Sommeil!"

I caught that boy napping one day.

"Vous dormez, mon ami?.. Sommeil, eh?" I cried.

The remark was enjoyed. There is so much charity in the hearts of boys!

Another boy had to translate a piece of Carlyle's "French Revolution": "'Their heads shall fall within a fortnight,' croaks the people's friend (Marat), clutching his tablets to write – Charlotte Corday has drawn her knife from the sheath; plunges it, with one sure stroke, into the writer's heart."

The end of this powerful sentence ran thus in the translation: "Charlotte Corday a tiré son poignard de la gaîne, et d'une main sûre, elle le plonge dans le cœur de celui qui écrivait."

When I remonstrated with the dear fellow, he pulled his dictionary out of his desk, and triumphantly pointed out to me:

"Writer (substantive), celui qui écrit."

And all the time his look seemed to say:

"What do you think of that? You may be a very clever man; but surely you do not mean to say that you know better than a dictionary!"

Oh, the French dictionary, that treacherous friend of boys!

The lazy ones take the first word of the list, sometimes the figurative pronunciation given in the English-French part.

Result: "I have a key" – "J'ai un ki."

The shrewd ones take the last word, to make believe they went through the whole list.

Result: "A chest of drawers" – "Une poitrine de caleçons."

The careless ones do not take the right part of speech they want.

Result: "He felt" – "Il feutra"; "He left" – "Il gaucha."

With my experience of certain French dictionaries published in England, I do not wonder that English boys often trust in Providence for the choice of words, although I cannot help thinking that as a rule they are most unlucky.

Very few boys have good dictionaries at hand. I know that Smith and Hamilton's dictionary (in two volumes) costs twenty shillings. But what is twenty shillings to be helped all through one's coaching? About the price of a good lawn-tennis racket.

I have seen boys show me, with a radiant air, a French dictionary they had bought for six-pence.

They thought they had made a bargain.

Oh, free trade! Oh, the cheapest market!

Sixpence for that dictionary! That was not very expensive, I own – but it was terribly dear.

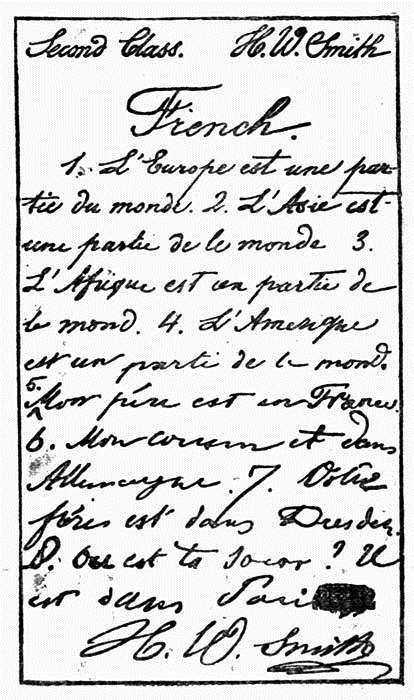

When an English boy is about to write out his French exercise, he invariably begins by heading the copy written with his best hand, on the first line.

"French,"This is to avoid any misunderstanding about the language he is going to use.

I have often felt grateful for that title.

Children are very great at titles and inscriptions.

Give them a little penny pocket-book, and their keen sense of ownership will make them go straightway and write their name and address on the first page. When this is done, they will entitle the book, and write on the top of each page: "Memorandum Book."

When I was at school, we French boys used to draw, on the back of the cover of our books, a merry-Andrew and a gibbet, with the inscription:

"Aspice Pierrot pendu,Quod librum n'a pas rendu.Si librum redidisset,Pierrot pendu non fuisset."I came across the following lines on some English boys' books:

"Don't steal this book for fear of shame,For here you see the owner's name;Or, when you die, the Lord will say:'Where is that book you stole away?'"

Boys' minds are like a certain place not mentioned in geographies: they are paved with good intentions. Before they begin their work, they choose their best nib (which always takes some time). This done, they carefully write their name and the title of the exercise. French looks magnificent. They evidently mean to do well. The first sentence is generally right and well written. In the second you perceive signs of flagging; it then gets worse and worse till the end, which is not legible. Judge for yourself, here is a specimen. It collapses with a blot half licked off.

Master H. W. S.'s flourish after his signature is not, as you see, a masterpiece of calligraphy; but it is not intended to be so. It is simply an overflow of relief and happiness at the thought that his exercise is finished.

Translate the flourish by —

"Done!!!"

H. W. S. is not particularly lucky with his genders. Fortunately for him, the French language possesses no neuter nouns, so that sometimes he hits on the right gender. For this he asks no praise. Providence alone is to be thanked for it.

Once he had to translate: "His conduct was good." He first put sa conduite. After this effort in the right direction, his conscience was satisfied, and he added, était bon. Why? Because an adjective is longer in the feminine than in the masculine, and with him and his like the former gender stands very little chance.

I remember two very strange boys. They were not typical, I am happy to say.

When the first of them was on, his ears would flap and go on flapping like the gills of a fish, till he had either answered the question or given up trying, when they would lie at rest flat against his head. If I said to him sharply: "Well, my boy, speak up; I can't hear," his ears would start flapping more vigorously than ever. Sometimes he would turn his eyes right over, to see if he could not find the answer written somewhere inside his head. This boy could set the whole of his scalp in motion, bring his hair right down to his eyes, and send it back again without the least difficulty. These performances were simply wonderful. The boys used to watch him with an interest that never flagged, and more than once I was near losing my countenance.

One day this poor lad fell in the playground, and cut his head open. We were all anxious to ascertain what it was he had inside his head that he always wanted to get at. The doctor found nothing remarkable in it.

The other boy was a fearful stammerer. The manner in which he managed to get help for his speech is worth relating. Whenever he had to read a piece of French aloud, he would utter the letter "F" before each French word, and they would positively come out easily. The letter "F" being the most difficult letter for stammerers to pronounce, I always imagined that he thought he would be all right with any sound, if he could only say "F" first.

He was successful.

A boy with whom you find it somewhat difficult to get on is the diffident one who always believes that the question you ask him is a "catch." He is constantly on guard, and surrounds the easiest question with inextricable difficulties. It is his misfortune to know that rules have exceptions, and he never suspects that it would enter your head to ask him for the illustration of a general rule.

He knows, for instance, that nouns ending in al form their plural by changing al into aux; but if you ask him for the plural of général, he will hesitate a long while, and eventually answer you, générals.

"Do you mean to say, my boy, that you do not know how to form the plural of nouns in al?"

"Yes, sir, but I thought général was an exception."

I pass over the wit who, being asked for the plural of égal, answered, "two gals."

A diverting little boy in the class-room is the one who always thinks "he has got it." It matters little to him what the question is, he has not heard the end of it when he lifts his hand to let you know he is ready.

"What is the future of savoir?"

"Please, sir, I know: je savoirai."

"Sit down, you ignoramus."

And he resumes his seat to sulk until you give him another chance. He wonders how it is you don't like his answers. His manner is generally affable; you see at once in him a mother's pet who is much admired at home, and thinks he is not properly appreciated at school.

Mother's pets are to be recognized at a glance. They are always clean and tidy in face and person. Unfortunately they often part their hair in the middle.

Such is not the testimonial that can be given to young H. He spends an hour and a pint of ink over every exercise.

He writes very badly.

To obtain a firm hold of his pen, he grasps the nib with the ends of his five fingers. I sometimes think he must use his two hands at once. He plunges the whole into the inkstand every second or two, and withdraws it dripping. He is smeared with ink all over; he rubs his hands in it, he licks it, he loves it, he sniffs it, he revels in it. He wishes he could drink it, and the ink-stands were wide enough for him to get his fist right into it.

This boy is a most clever little fellow. When you can see his eyes, they are sparkling with mischief and intelligence. A beautiful, dirty face; a lovely boy, though an "unwashed."

A somewhat objectionable boy, although he is not responsible for his shortcomings, is the one who has been educated at home up to twelve or fourteen years of age.

Before you can garnish his brain, you have to sweep it. You have to replace the French of his nursery governess – who has acquired it on the Continong– by a serious knowledge of avoir and être.

He comes to school with a testimonial from his mother, who is a good French scholar, to the effect that he speaks French fluently.

You ask him for the French of

"It is twelve o'clock,"and he answers with assurance:

"C'est douze heures."You ask him next for the French of

"How do you do?"and he tells you:

"Comment ça va-t-il?"You call upon him to spell it, and he has no hesitation about it: "Comment savaty?"

You then test his knowledge of grammar by asking him the future of vouloir, and you immediately obtain: "Je voulerai."

You tell him that his French is very shaky, and you decide on putting him with the beginners.

The following day you find a letter awaiting you at school. It is from his indignant mother. She informs you that she fears her little boy will not learn much in the class you have put him in. He ought to be in one of the advanced classes. He has read Voltaire4 and can speak French.

She knows he can, she heard him at Boulogne, and he got on very well. The natives there had no secrets for him; he could understand all they said.

You feel it to be your duty not to comply with the lady's wishes, and you have made a bitter enemy to yourself and the school.

This boy never takes for granted the truth of the statements you make in the class-room. What you say may be all right; but when he gets home he will ask his mamma if it is all true.

He is fond of arguing, and has no sympathy with his teacher. He tries to find him at fault.

A favorite remark of his is this:

"Please, sir, you said the other day that so-and-so was right. Why do you mark a mistake in my exercise to-day?"

You explain to him why he is wrong, and he goes back to his seat grumbling. He sees he is wrong; but he is not cured. He hopes to be more lucky next time.

When you meet his mother, she asks you what you think of the boy.

"A very nice boy indeed," you say; "only I sometimes wish he had more confidence in me; he is rather fond of arguing."

"Oh!" she exclaims, "I know that. Charley will never accept a statement before he has discussed it and thoroughly investigated it."

As a set-off for Charley, there is the boy who has a blind confidence in you. All you say is gospel to him, and if you were to tell him that the French word voisin is pronounced kramshaka, he would unhesitatingly say kramshaka.

Nothing astonishes him; he has taken for his motto the Nil admirari of Horace. He would see three circumflex accents on the top of a vowel without lifting his eyebrows. He is none of the inquiring and investigating sort.

Another specimen of the Charley type is the one who has been coached for the public school in a Preparatory School for the Sons of Gentlemen, kept by ladies.

This boy has always been well treated. He is fat, rubicund, and unruly. His linen is irreproachable. The ladies told him he was good-looking, and his hair, which he parts into two ailes de pigeon, is the subject of his incessant care.

He does not become "a man" until his comrades have bullied him into a good game of Rugby football.

On the last bench, right in the corner, you can see young Bully. He does not seek after light, he is not an ambitious boy, and the less notice you take of him the better he is pleased. His father says he is a backward boy. Bully is older and taller than the rest of the class. For form's sake you are obliged to request him to bring his work, but you have long ago given up all hope of ever teaching him any thing. He is quiet and unpretending in class, and too sleepy to be up to mischief. He trusts that if he does not disturb your peace you will not disturb his. When a little boy gives you a good answer, it arouses his scorn, and he not uncommonly throws at him a little smile of congratulation. If you were not a good disciplinarian, he would go and give him a pat on the back, but this he dares not do.

When you bid him stand up and answer a question, he begins by leaning on his desk. Then he gently lifts his hinder part, and by slow degrees succeeds in getting up the whole mass. He hopes that by this time you will have passed him and asked another boy to give you the answer. He is not jealous, and will bear no ill-will to the boy who gives you a satisfactory reply.

If you insist on his standing up and giving sign of life, he frowns, loosens his collar, which seems to choke him, looks at the floor, then at the ceiling, then at you. Being unable to utter a sound, he frowns more, to make you believe that he is very dissatisfied with himself.

"I know the answer," he seems to say; "how funny, I can't recollect it just now."

As you cannot waste any more time about him, you pass him; a ray of satisfaction flashes over his face, and he resumes his corner hoping for peace.

The little boys dare not laugh at him, for he is the terror of the playground, where he takes his revenge of the class-room.

His favorite pastime in the playground is to teach little boys how to play marbles. They bring the marbles, he brings his experience. When the bell rings to call the boys to the class-rooms, he has got many marbles, the boys a little experience.

One of my pet aversions is the young boy who arrays5 himself in stand-up collars and white merino cravats.

George Eliot, I believe, says somewhere that there never was brain inside a red-haired head. I think she was mistaken. I have known very clever boys with red hair.

But what I am positive about is that there is no brain on the top of boys ornamented with stand-up collars.

Young Bully wears them. He comes to school with his stick, and whenever you want a match to light the gas with he can always supply you, and feels happy he is able for once to oblige you.

In some boys I have often deplored the presence of two ears. What you impart through one immediately escapes through the other. Explain to them a rule once a week, they will always enjoy hearing it again. It will always be new to them. Their lives will ever be a series of enchantments and surprises.

You must persevere, and repeat things to them a hundred times, if ninety-nine will not do. Who knows there is not a John Wesley among them?

"I remember," once said this celebrated divine, "hearing my father say to my mother: 'How could you have the patience to tell that blockhead the same thing twenty times over?' 'Why,' said she, 'if I had told him only nineteen times, I should have lost all my labor.'"