полная версия

полная версияCastles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces

The mediæval country house was a château; when it was protected by walls and moats it became a castle or château-fort; a distinction to be remarked.

The château of the middle ages was not only the successor of the Roman stronghold, but it was a villa or place of residence as well; when it was fortified it was a chastel.

A castle might be habitable, and a château might be a species of stronghold, and thus the mediæval country house might be either one thing or the other, but still the distinction will always be apparent if one will only go deeply enough into the history of any particular structure.

Light and air, which implies frequent windows, have always been desirable in all habitations of man, and only when the château bore the aspects of a fortification were window openings omitted. If it was an island castle, a moat-surrounded château, – as it frequently was in later Renaissance times, – windows and doors existed in profusion; but if it were a feudal fortress, such as one most frequently sees in the Pyrenees, openings at, or near, the ground-level were few and far between. Such windows as existed were mere narrow slits, like loop-holes, and the entrance doorway was really a fortified gate or port, frequently with a portcullis and sometimes with a pont-levis.

The origin of the word château (castrum, castellum, castle) often served arbitrarily to designate a fortified habitation of a seigneur, or a citadel which protected a town. One must know something of their individual histories in order to place them correctly. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, châteaux in France multiplied almost to infinity, and became habitations in fact.

In reality the middle ages saw two classes of great châteaux go up almost side by side, the feudal château of the tenth to the fifteenth centuries, and the frankly residential country houses of the Renaissance period which came after.

For the real, true history of the feudal châteaux of France, one cannot do better than follow the hundred and fifty odd pages which Viollet-le-Duc devoted to the subject in his monumental “Dictionnaire Raisonée d’Architecture.”

In the Midi, all the way from the Italian to the Spanish frontiers, are found the best examples of the feudal châteaux, mere ruins though they be in many cases. In the extreme north of Normandy, at Les Andelys, Arques and Falaise, at Pierrefonds and Coucy, these military châteaux stand prominent too, but mid-France, in the valley of the Loire, in Touraine especially, is the home of the great Renaissance country house.

The royal châteaux, the city dwellings and the country houses of the kings have perhaps the most interest for the traveller. Of this class are Chenonceaux and Amboise, Fontainebleau and St. Germain, and, within the scope of this book, the paternal château of Henri Quatre at Pau.

It is not alone, however, these royal residences that have the power to hold one’s attention. There are others as great, as beautiful and as replete with historic events. In this class are the châteaux at Foix, at Carcassonne, at Lourdes, at Coarraze and a dozen other points in the Pyrenees, whose architectural splendours are often neglected for the routine sightseeing sanctioned and demanded by the conventional tourists.

There are no vestiges of rural habitations in France erected by the kings of either of the first two races, though it is known that Chilperic and Clotaire II had residences at Chelles, Compiègne, Nogent, Villers-Cotterets, and Creil, north of Paris.

The pre-eminent builder of the great fortress châteaux of other days was Foulques Nerra, and his influence went wide and far. These establishments were useful and necessary, but they were hardly more than prison-like strongholds, quite bare of the luxuries which a later generation came to regard as necessities.

The refinements came in with Louis IX. The artisans and craftsmen became more and more ingenious and artistic, and the fine tastes and instincts of the French with respect to architecture soon came to find their equal expression in furnishings and fitments. Hard, high seats and beds, which looked as though they had been brought from Rome in Cæsar’s time, gave way to more comfortable chairs and canopied beds, carpets were laid down where rushes were strewn before, and walls were hung with cloths and draperies where grim stone and plaster had previously sent a chill down the backs of lords and ladies. Thus developed the life in French châteaux from one of simple security and defence, to one of luxurious ease and appointments.

The sole medium of communication between many of the French provinces, at least so far as the masses were concerned, was the local patois. All who did not speak it were foreigners, just as are English, Americans or Germans of to-day. The peoples of the Romance tongue stood in closer relation, perhaps, than other of the provincials of old, and the men of the Midi, whether they were Gascons from the valley of the Garonne, or Provençaux from the Bouches-du-Rhône were against the king and government as a common enemy.

The feudal lords were a gallant race on the whole; they didn’t spend all their time making war; they played boules and the jeu-de-paume, and held court at their château, where minstrels sang, and knights made verses for their lady loves, and men and women amused themselves much as country-house folk do to-day.

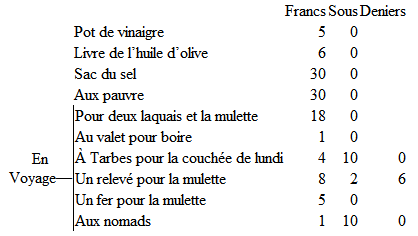

The following, extracted from the book of accounts of one of the minor noblesse of Béarn in the sixteenth century, is intimate and interesting. The master of this feudal household had a system of bookkeeping which modern chatelains might adopt with advantage. The items are curiously disposed.

Evidently “la mulette” was a very necessary adjunct and required quite as much as its master.

CHAPTER III

THE PYRENEES – THEIR GEOGRAPHY AND TOPOGRAPHY

ONE of the great joys of the traveller is the placid contemplation of his momentary environment. The visitor to Biarritz, Pau, Luchon, Foix or Carcassonne has ever before his eyes the massive Pyrenean bulwark between France and Spain; and the mere existence of this natural line of defence accounts to no small extent for the conditions of life, the style of building, and even the manners of the men who live within its shadow.

The Pyrenees have ever formed an undisputed frontier boundary line, though kingdoms and dukedoms, buried within its fastnesses or lying snugly enfolded in its gentle valleys, have fluctuated and changed owners so often that it is difficult for most people to define the limits of French and Spanish Navarre or the country of the French and Spanish Basques. It is still more difficult when it comes to locating the little Pyrenean republic of Andorra, that tiniest of nations, a little sister of San Marino and Monaco. Some day the histories of these three miniature European “powers” (sic) should be made into a book. It would be most interesting reading and a novelty.

Unlike the Alps, the Pyrenees lack a certain impressive grandeur, but they are more varied in their outline, and form a continuous chain from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, while their gently sloping green valleys smile more sweetly than anything of the kind in Switzerland or Savoie.

They possess character, of a certain grim kind to be sure, particularly in their higher passes, and a general air of sterility, which, however, is less apparent as one descends to lower levels. The very name of Pyrenees comes probably from the word biren, meaning “high pastures,” so this refutes the belief that they are not abundantly endowed with this form of nature’s wealth.

From east to west the chain of the Pyrenees has a length of four hundred and fifty kilometres, or, following the détours of the crests of the Hispano-Français frontier, perhaps six hundred. Between Pau and Huesca their width, counting from one lowland plain to another, is a trifle over a hundred and twenty kilometres, the slope being the most rapid on the northern, or French, side. The Pyrenees are less thickly wooded than the Savoian Alps, and there is very much less perpetual snow and fewer glaciers.

In reality they are broken into two distinct parts by the Val d’Aran, forming the Pyrénées-Orientales and the Pyrénées-Occidentales. Of the detached mountain masses, the chief is the Canigou, lying almost by the Mediterranean shore, and a little northward of the main chain. Its highest peak is the Puigmal (puig or puy being the Languedoçian word for peak), rising to nearly three thousand metres.

For long the Canigou was supposed to be the loftiest peak of the Pyrenees, but the Pic du Midi exceeds it by a hundred metres. However, this well proportioned, isolated mass looks more pretentious than it really is, standing, as it does, quite away from the main chain. From its peak Marseilles can be seen – by a Marseillais, who will also fancy that he can hear the turmoil of the Cannebière and detect the odour of the saffron in his beloved bouillabaise. At any rate one can certainly see as much of the earth’s surface spread out before him here as from any other spot of which he has recollection.

The Pyrénées-Occidentales abound in more numerous and better defined mountains than the more easterly portion. Here are the famous Monts Maudits, with the Pic de Nethou, the highest of the Pyrenees (three thousand four hundred and four metres), with a summit plateau or belvedere perhaps twenty metres in length by five in width.

The Vignemal (three thousand two hundred and ninety-eight metres) is the highest peak wholly on French soil and dominates the famous col, or pass, known as the Brèche de Roland.

The Pic du Midi, back of Bigorre, is justly the best known of all the crests of the Pyrenees. Its height is two thousand eight hundred and seventy-seven metres, and it is worthy of a special study, and a book all to itself. The observatory recently established here is one of the chefs-d’œuvre of science. The astronomical, climatological and geographical importance of this prominent peak was already marked out on the maps of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and its glory has been often sung in verse by Guillaume Saluste, Sire du Bartas, gentilhomme Gascon; and by Bernard Palissy, better known as a potter than as a poet.

Towards the Gulf of Gascony the Pyrenees send out their ramifications in much gentler slopes than on the Mediterranean side. Forests and pastures are more profuse and luxuriant, but the peaks are still of granite, as they mostly are throughout the range. Grouped along the flanks of the river Bidassoa this section of the chain is known to geographers as the “Montagnes du pays Basque.”

At the foot of these Basque Mountains passes the lowest level route between France and Spain, – that followed by the railway and the “Route Internationale, Paris-Madrid.”

This easy and commodious passage of the Pyrenees has ever been the theatre of the chief struggles between the peoples of the Spanish peninsula and France. At Ronçevaux the rear-guard of the army of Charlemagne – “his paladins and peers” – were destroyed in 778, and it was here that the French and Spanish fought in 1794 and 1813.

The French slopes of the Pyrenees belong almost wholly to the basin or watershed of the Garonne, one of the four great waterways of France, the other three being the Loire, the Seine and the Rhône. In the upper valley of the Garonne is the Plateau de Lannemazan. It lies in reality between the Garonne and the Adour. The Adour on the west and the Tech on the east, with their tributaries, play an important part in draining off the waters from the mountain sources, but they are entirely overshadowed by the Garonne, which, rising in Spain, in the Val d’Aran, flows six hundred and five kilometres before reaching salt water below Bordeaux, through its estuary the Gironde. Nearly five hundred kilometres of this length are navigable, and the economic value of this river to Agen, Montauban and Toulouse is very great.

Between the Adour and the Gironde lies that weird morass-like region of the Landes, once peopled only by sheep-herders on stilts and by charcoal-burners, but now producing a quantity of resin and pine which is making the whole region prosperous and content.

The source of the Garonne is at an altitude of nearly two thousand metres, and is virtually a cascade. Another tiny source, known as the Garonne-Oriental, swells the flood of the parent stream by flowing into it just below St. Gaudens, the nearest “big town” of France to the Spanish frontier.

The Ariège is the only really important tributary entering the Garonne from the region of the Pyrenees. Its length is a hundred and fifty-seven kilometres, and its source is on the Pic Nègre, at an altitude of two thousand metres, three kilometres from the frontier, but on French soil. It waters two important cities of the Comté de Foix, the capital Foix and Pamiers.

On the west, the chain of the Pyrenees slopes gently down to the great bight, known so sadly to travellers by sea as the Bay of Biscay. From the mouth of the Gironde southward it is further designated as the Golfe de Gascogne. There is no perceptible indentation of the coast line to indicate this, but its waters bathe the sand dunes of the Landes, the Basque coasts, and the extreme northeastern boundary of Spain.

The shore-line is straight, uniformly monotonous and inhospitable, the great waves which roll in from the Atlantic beating up a soapy surf and long dikes of sand in weird, unlovely contours. For two hundred and forty kilometres, all along the shore-line of the Gironde and the Landes, this is applicable, the only relief being the basin of Archachon (Bordeaux’ own special watering-place), the port of Bayonne, – at the mouth of the Adour, – the delightful rocky picturesqueness immediately around Biarritz, and Saint-Jean-de-Luz and its harbour, and the estuary of the Bidassoa, that epoch-making river which, with the crest of the Pyrenees, marks the Franco-Espagnol frontier.

The French coast line at the easterly termination of the Pyrenees possesses an entirely different aspect from that of the west. Practically there is no tide in the Mediterranean, and the gateway between France and Spain through the eastern Pyrenees is less gracious than that on the west. The Pyrénées-Orientales come plump down to the blue waters of the great inland sea just north of Cap Créus with little or no intimation of a slope.

The frontier commences at Cap Cerbère, and at Port Vendres (the Portus-Veneris of the ancients) one finds one of the principal Mediterranean sea ports of France, and the nearest to the great French possessions in Africa.

On Cap Créus in Spain, and on Cap Bear in France, at an elevation of something over two hundred metres, are two remarkable lighthouses whose rays carry a distance of over forty kilometres seaward.

The étangs, Saint Nazaire and Leucate, cut the coast line here, and three tiny rivers, whose sources are high up in the mountain valleys of the Tech, the Tet and the Aglay, flow into the sea before Cap Leucate, the boundary between old Languedoc and the Comté de Roussillon.

Off-shore is the tempestuous Golfe des Lions, where the lion banners of the Arlesien ships floated in days gone by. The Aude, the Orb and the Hérault mingle their waters with the Mediterranean here, and on the Montagne d’Agde rises another of those remarkable French lighthouses, this one throwing its light a matter of forty-five kilometres seawards.

With Perpignan, Narbonne, Béziers and Agde behind, one draws slowly out from under the shadow of the Pyrenees until the soil flattens out into a powdery, dusty plain, with here and there a pond, or great bay, of soft, brackish water, whose principal value lies in its fecundity at producing mosquitoes.

Aigues-Mortes cradles itself on the shores of one of these great inlets of the Mediterranean, and Saintes Maries on another. Little gulfs, canals, dwarf seaside pines, cypresses, olive trees and vineyards are the chief characteristics of the landscape, while inland the surface of the soil rolls away in gentle billows towards Nîmes, Montpellier and St. Giles, with the flat plain of the Camargue lying between.

Since the Christian era began, it is assumed that this coast line between the Pyrenees and the Rhône has advanced a matter of fourteen kilometres seaward, and since Aigues-Mortes, which now lies far inland, is known to be the port from which the sainted Louis set out on his Crusade, there is no gainsaying the statement. The immediate region surrounding Aigues-Mortes is a most fascinating one to visit, but would be a terrible place in which to be obliged to spend a life-time.

Between Roussillon and Spain there are fifteen passes by which one may cross the chain of the Pyrenees, though indeed two only are practicable for wheeled traffic.

The Col de Perthus is the chief one, and is traversed by the ancient “Route Royale” from Paris to Barcelona. There is a town by the same name, with a population of five hundred and a really good hotel. It’s worth making the journey here just to see how a dull French village can sleep its time away. The passage is defended by the fine Fortress de Bellegarde. It was on the Col de Perthus that Pompey erected the famous “trophy,” surmounted by his statue bearing the following legend:

FROM THE ALPS TO THE ULTERIOR EXTREMITY OF SPAIN, POMPEY HAS FORCED SUBMISSION TO THE ROMAN REPUBLIC FROM EIGHT HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-SIX CITIES AND TOWNS.

Twenty years after, Caesar erected another tablet beside the former. No trace of either remains to-day, and there are only frontier boundary stones marking the territorial limits of France and Spain, which replace those torn down in the Revolution.

Proceeding by the coast line, a difficult road into Spain lies by the Col de Banyuls, just where the Pyrenees plunge beneath the Mediterranean, a mere shelf of a road.

The cirques, or great amphitheatres of mountains, are a characteristic of the Pyrenees, and the Cirque de Gavarnie is the king of them all. It represents, very nearly, a sheer perpendicular wall rising to a height of five hundred metres, and three thousand five hundred metres in circumference. Perpetual snow is an accompaniment of some of its gorges and neighbouring peaks, and twelve cascades tumble down its rock walls at various points. There is nothing quite so impressive in the world – outside Yosemite or the Yellowstone.

Gavarnie, its cirque and its village, is the natural wonder of the Pyrenees. Said Victor Hugo: “Grand nom, petit village.” To explore the Cirque de Gavarnie is a passion with many; when you get in this state of mind you become what the touring Frenchman knows as a “gavarniste,” as an Alpine climber becomes an “alpiniste.”

As for the climate of the Pyrenees, it is, for a mountain region, soft and mild; not so mild as that of the French Riviera perhaps, nor of Barcelona, nor San Sebastian in Spain, but on the whole not cold, and certainly more humid than in the Alpes-Maritimes, on the Côte d’Azur.

Generally blowing from the northwest in winter, the wind accumulates great masses of cloud in the bight of the Golfe de Gascogne and sweeps them up against the barrier of the Pyrenees, there to be held in suspension until an exceedingly stiff wind blows them away or the sun burns them off. The French Riviera is cursed with the mistral, but it has the blessing of almost continual sunshine, while in the Pyrénées-Occidentales the wind is less strong as it comes only from the sea in the northwest, instead of from the north by the Rhône valley, and the “disagreeable months” (November, December and January) often bring damp and humid, if not frigidly cold weather with them.

The rainfall is often as much as eight decimetres per annum in the Landes, one metre in the Pyrenees proper, and a metre and a half in the Basque country. The average rainfall for France is approximately eight decimetres, perhaps thirty-two inches.

In the Pyrenees the temperature is, normally, neither very hot nor very cold. Perpignan is the warmest in winter. Its average is 15 °Centigrade (59° F.), about that of Nice, whilst that for France is 6 °Centigrade (43° F.).

The climate of the Pyrenees comes within the climat Girondin, and the average for the year is 13 °Centigrade. The climat-maritime is a further division, and is considerably more elevated in degree. This comes from the western and northwestern winds off the sea, which, it may be remarked, almost invariably bring rain with them. At Montauban the saying is: “Montagne claire, Bordeaux obscure, pluie à coup sur.” In Gascogne: “Jamais pluie au printemps ne passe pour mauvais temps.” At Bordeaux the average summer temperature is but 29 °Centigrade, at Toulouse 21.5 °Centigrade and Pau about the same, with a winter temperature often 4° or 5° below zero Centigrade.

The general aspect of the region of the Pyrenees is one of the most varied and agreeable in all southern France. There is a grandeur and natural character about it that has not fallen before the march of twentieth century progress, save in the “resorts,” such as Biarritz or Pau; and yet the primitiveness and savagery is not so uncomfortable as to make the traveller long for the super-civilization of great capitals. It is virgin in its beauty and varied wildness, and yet it is a soft, pleasant land where even the winter snows of the mountains seem less rigorous than the snow and cold of Savoie or Switzerland. On one side is the great bulwark of the Pyrenees, and on two others the dazzling waters of the ocean, while to the north the valley of the Garonne, west of the Cevennes, is not at all a frigid, austere, frost-bound region, save only in the very coldest “snaps.”

The ranges of foothills in the Pyrenees divide the surface of the land into slopes and valleys every bit as charming as those of Switzerland, and yet oh! so different! And the fresh, limpid rivulets and rivers are real rivers, and not mere trickling brooks, whose colouring and transparency are the marvel of all who view. The majesty of the sea on either side, and of the mountains between, makes the very aspect of life luxurious and less hard than that in the more northerly Alpine climes, and above all the outlook on life is French, and not that money-grabbing Anglo-German-Swiss commercialism which the genuine traveller abhors. He sees less of that sort of thing here in the Pyrenees, even at Pau and Biarritz, than anywhere else in southern Europe.

At Nice, Monte Carlo, Naples, Capri, along the Italian lakes, and everywhere in French, German or Italian speaking Switzerland, one must pay! pay! pay! continually, and often for nothing. Here you pay for what you get, and then not always its full value, according to standards with which you have previously become familiar. The Pyrenees form quite the ideal mountain playground of Europe.

The Basses-Pyrénées, made up from the coherent masses of Navarre, the Basque country, Béarn, and a part of Chalosse and the Landes, contains a superficial area of seven hundred and sixty-three thousand nine hundred and ninety French acres. Its name comes naturally enough from the western end of the Pyrenean mountain chain.

Throughout, the department is watered by innumerable streams and rivulets, whose banks and beds are as reminiscent of romanticism as any waterways extant. The Adour is one of the “picture-rivers” of the world; it joins the rustling, tumbling Nive, as it rushes down by Cambo from the Spanish valleys, and forms the port of Bayonne.

The Gave de Pau commences in the high Pyrenees, in the wonderfully spectacular Cirque de Gavarnie, literally in a cascade falling nearly one thousand three hundred feet, perhaps the highest cascade known in the four quarters of the globe, or as the French say, “in the five parts of the world,” which is more quaint if less literal.

The Gave d’Oloron has its birth in the valley of the Aspe, and is a tributary of the Gave de Pau. It is what one might call pretty, but has little suggestion of the scenic splendour of the latter.

The Bidassoa is one of the world’s historic rivers. It forms the Atlantic frontier between France and Spain, and was the scene of Wellington’s celebrated “Passage of the Bidassoa” in 1813, also of a still more famous historical event which took place centuries before on the Ile des Faisans.