полная версия

полная версияThe Collected Works in Verse and Prose of William Butler Yeats. Volume 3 of 8. The Countess Cathleen. The Land of Heart's Desire. The Unicorn from the Stars

NOTE BY FLORENCE FARR

I made an interesting discovery after I had been elaborating the art of speaking to the psaltery for some time. I had tried to make it more beautiful than the speaking by priests at High Mass, the singing of recitative in opera and the speaking through music of actors in melodrama. My discovery was that those who had invented these arts had all said about them exactly what Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch and Mr. W. B. Yeats said about my art. Anyone can prove this for himself who will go to a library and read the authorities that describe how early liturgical chant, plain-song and jubilations or melismata were adapted from the ancient traditional music; or if they read the history of the beginning of opera and the ‘nuove musiche’ by Caccini, or study the music of Monteverde and Carissimi, who flourished at the beginning of the seventeenth century, they will find these masters speak of doing all they can to give an added beauty to the words of the poet, often using simple vowel sounds when a purely vocal effect was to be made whether of joy or sorrow. There is no more beautiful sound than the alternation of carolling or keening and a voice speaking in regulated declamation. The very act of alternation has a peculiar charm.

Now to read these records of music of the eighth and seventeenth centuries one would think that the Church and the opera were united in the desire to make beautiful speech more beautiful, but I need not say if we put such a hope to the test we discover it is groundless. There is no ecstasy in the delivery of ritual, and recitative is certainly not treated by opera-singers in a way that makes us wish to imitate them.

When beginners attempt to speak to musical notes they fall naturally into the intoning as heard throughout our lands in our various religious rituals. It is not until they have been forced to use their imaginations and express the inmost meaning of the words, not until their thought imposes itself upon all listeners and each word invokes a special mode of beauty, that the method rises once more from the dead and becomes a living art.

It is the belief in the power of words and the delight in the purity of sound that will make the arts of plain-chant and recitative the great arts they are described as being by those who first practised them.

THE WIND BLOWS OUT OF THE GATES OF THE DAY

THE HAPPY TOWNLAND

I HAVE DRUNK ALE FROM THE COUNTRY OF THE YOUNG

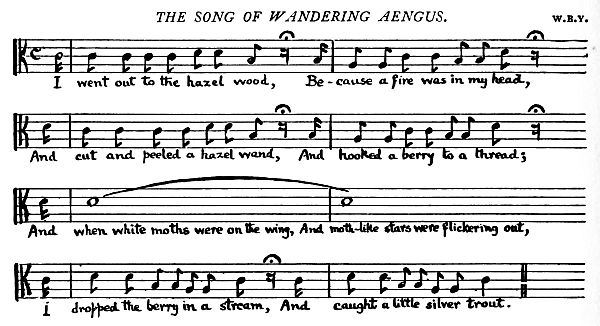

THE SONG OF WANDERING AENGUS

THE HOST OF THE AIR

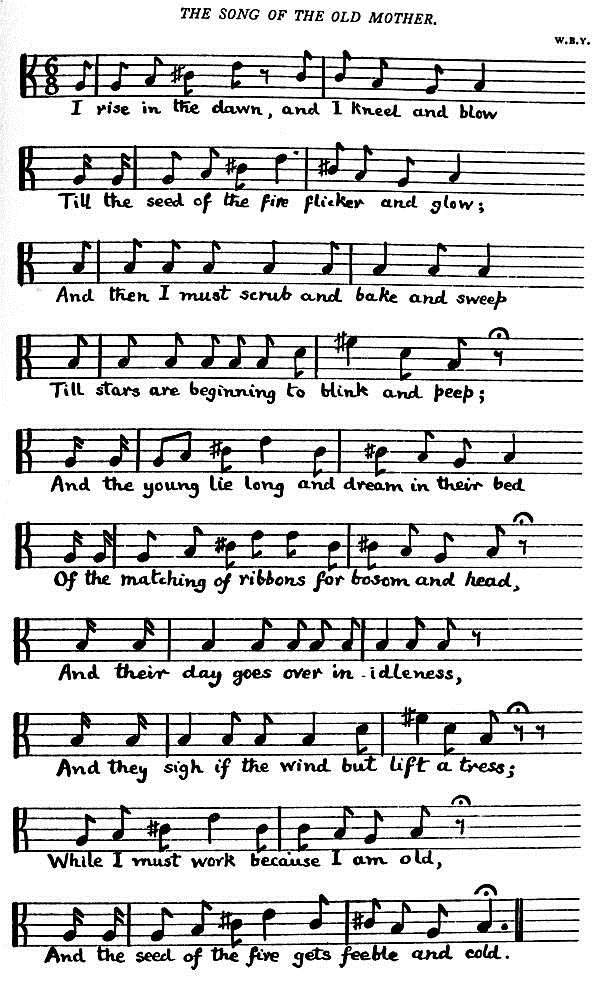

THE SONG OF THE OLD MOTHER

1

I have left them out of this edition as Lady Gregory’s Cuchulain of Muirthemne and Gods and Fighting Men have made them unnecessary. When I began to write, the names of the Irish heroes were almost unknown even in Ireland.

2

Mr. Synge has outdone me with his Play Boy of the Western World, which towards the end of the week had more than three times the number in the pit alone. Counting the police inside and outside the theatre, there were, according to some evening papers, five hundred. —March, 1908.

3

The Violinist should time the music so as to finish when Aibric says “For everything is gone”.

4

The music as written suits my speaking voice if played an octave lower than the notation. – F.F.

5

To be spoken an octave lower than it would be sung. – F.F.