полная версия

полная версияThe Collected Works in Verse and Prose of William Butler Yeats. Volume 3 of 8. The Countess Cathleen. The Land of Heart's Desire. The Unicorn from the Stars

Et Ketty n’avait plus une obole, car elle avait abandonné son château aux malheureux.

Elle passa douze heures dans les larmes et le deuil, arrachant ses cheveux couleur de soleil et meurtrissant son sein couleur du lis: puis elle se leva résolue, animée par un vif sentiment de désespoir.

Elle se rendit chez les marchands d’âmes.

– Que voulez-vous? dirent ils.

– Vous achetez des âmes?

– Oui, un peu malgré vous, n’est ce pas, sainte aux yeux de saphir?

– Aujourd’hui je viens vous proposer un marché, reprit elle.

– Lequel?

– J’ai une âme a vendre; mais elle est chère.

– Qu’importe si elle est précieuse? l’âme, comme le diamant, s’apprécie à sa blancheur.

– C’est la mienne, dit Ketty.

Les deux envoyés de Satan tressaillirent. Leurs griffes s’allongèrent sous leurs gants de cuir; leurs yeux gris étincelèrent: – l’âme, pure, immaculée, virginale de Ketty!.. c’était une acquisition inappréciable.

– Gentille dame, combien voulez-vous?

– Cent cinquante mille écus d’or.

– C’est fait, dirent les marchands; et ils tendirent à Ketty un parchemin cacheté de noir, qu’elle signa en frissonnant.

La somme lui fut comptée.

Dès qu’elle fut rentrée, elle dit au majordome:

– Tenez, distribuez ceci. Avec la somme que je vous donne les pauvres attendront la huitaine nécessaire et pas une de leurs âmes ne sera livrée au démon.

Puis elle s’enferma et recommanda qu’on ne vint pas la déranger.

Trois jours se passèrent; elle n’appela pas; elle ne sortit pas.

Quand on ouvrit sa porte, on la trouva raide et froide: elle était morte de douleur.

Mais la vente de cette âme si adorable dans sa charité fut déclarée nulle par le Seigneur: car elle avait sauvé ses concitoyens de la mort éternelle.

Après la huitaine, des vaisseaux nombreux amenèrent à l’Irlande affamée d’immenses provisions de grains.

La famine n’était plus possible. Quant aux marchands, ils disparurent de leur hôtellerie, sans qu’on sût jamais ce qu’ils étaient devenus.

Toutefois, les pêcheurs de la Blackwater prétendent qu’ils sont enchaînés dans une prison souterraine par ordre de Lucifer jusqu’au moment où ils pourront livrer l’âme de Ketty qui leur a échappé. Je vous dis la légende telle que je la sais.

– Mais les pauvres l’ont raconté d’âge en âge et les enfants de Cork et de Dublin chantent encore la ballade dont voici les derniers couplets: —

Pour sauver les pauvres qu’elle aimeKetty donnaSon esprit, sa croyance même;Satan payaCette âme au dévoûment sublime,En écus d’or,Disons pour racheter son crimeConfiteor.Mais l’ange qui se fit coupablePar charitéAu séjour d’amour ineffableEst remonté.Satan vaincu n’eut pas de priseSur ce cœur d’or;Chantons sous la nef de l’église,Confiteor.N’est ce pas que ce récit, né de l’imagination des poètes catholiques de la verte Erin, est une véritable récit de carême?

The Countess Cathleen was acted in Dublin in 1899 with Mr. Marcus St. John and Mr. Trevor Lowe as the First and Second Demon, Mr. Valentine Grace as Shemus Rua, Master Charles Sefton as Teig, Madame San Carola as Maire, Miss Florence Farr as Aleel, Miss Anna Mather as Oona, Mr. Charles Holmes as the Herdsman, Mr. Jack Wilcox as the Gardener, Mr. Walford as a Peasant, Miss Dorothy Paget as a Spirit, Miss M. Kelly as a Peasant Woman, Mr. T. E. Wilkenson as a Servant, and Miss May Whitty as the Countess Cathleen. They had to face a very vehement opposition stirred up by a politician and a newspaper, the one accusing me in a pamphlet, the other in long articles day after day, of blasphemy because of the language of the demons in the first act, and because I made a woman sell her soul and yet escape damnation, and of a lack of patriotism because I made Irish men and women, who it seems never did such a thing, sell theirs. The politician or the newspaper persuaded some forty Catholic students to sign a protest against the play, and a Cardinal, who avowed that he had not read it, to make another, and both politician and newspaper made such obvious appeals to the audience to break the peace, that some score of police2 were sent to the theatre to see that they did not. I have, however, no reason to regret the result, for the stalls, containing almost all that was distinguished in Dublin, and a gallery of artisans, alike insisted on the freedom of literature, and I myself have the pleasure of recording strange events.

The play has since been revived in New York by Miss Wycherley, but I did not see her performance.

The Land of Heart’s Desire.– This little play was produced at the Avenue Theatre in the spring of 1894, with the following cast: – Maurteen Bruin, Mr. James Welch; Shawn Bruin, Mr. A. E. W. Mason; Father Hart, Mr. G. R. Foss; Bridget Bruin, Miss Charlotte Morland; Maire Bruin, Miss Winifred Fraser; A Faery Child, Miss Dorothy Paget. It ran for a little over six weeks. It was revived in America in 1901, when it was taken on tour by Mrs. Lemoyne. It was again played, under the auspices of the Irish Literary Society of New York, in 1903, and has lately been played in San Francisco.

The Unicorn from the Stars.– Some years ago I wrote in a fortnight with the help of Lady Gregory and another friend a five act tragedy called Where there is Nothing. I wrote at such speed that I might save from a plagiarist a subject that seemed worth the keeping till greater knowledge of the stage made an adequate treatment possible. I knew that my first version was hurried and oratorical, with events cast into the plot because they seemed lively or amusing in themselves, and not because they grew out of the characters and the plot; and I came to dislike a central character so arid and so dominating. We cannot sympathise with a man who sets his anger at once lightly and confidently to overthrow the order of the world; but our hearts can go out to him, as I think, if he speak with some humility, so far as his daily self carries him, out of a cloudy light of vision. Whether he understand or know, it may be that the voices of Angels and Archangels have spoken in the cloud and whatever wildness come upon his life, feet of theirs may well have trod the clusters. I began with this new thought to dictate the play to Lady Gregory, but since I had last worked with her, her knowledge of the stage and her mastery of dialogue had so increased that my imagination could not go neck to neck with hers. I found myself, too, with an old difficulty, that my words flow freely alone when my people speak in verse, or in words that are like those we put into verse; and so after an attempt to work alone I gave my scheme to her. The result is a play almost wholly hers in handiwork, which I can yet read, as I have just done after the stories of The Secret Rose, and recognize thoughts, a point of view, an artistic aim which seem a part of my world. Her greatest difficulty was that I had given her for chief character a man so plunged in trance that he could not be otherwise than all but still and silent, though perhaps with the stillness and the silence of a lamp; and the movement of the play as a whole, if we were to listen to hear him, had to be without hurry or violence. The strange characters, her handiwork, on whom he sheds his light, delight me. She has enabled me to carry out an old thought for which my own knowledge is insufficient and to commingle the ancient phantasies of poetry with the rough, vivid, ever-contemporaneous tumult of the road-side; to create for a moment a form that otherwise I could but dream of, though I do that always, an art that prophesies though with worn and failing voice of the day when Quixote and Sancho Panza long estranged may once again go out gaily into the bleak air. Ever since I began to write I have awaited with impatience a linking, all Europe over, of the hereditary knowledge of the country-side, now becoming known to us through the work of wanderers and men of learning, with our old lyricism so full of ancient frenzies and hereditary wisdom, a yoking of antiquities, a Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

The Unicorn from the Stars was first played at the Abbey Theatre on November 23rd, 1907, with the following cast: – Father John, Ernest Vaughan; Thomas Hearne, a coachbuilder, Arthur Sinclair; Andrew Hearne, brother of Thomas, J. A. O’Rourke; Martin Hearne, nephew of Thomas, F. J. Fay; Johnny Bacach, a beggar, W. G. Fay; Paudeen, J. M. Kerrigan; Biddy Lally, Maire O’Neill; Nanny, Brigit O’Dempsey.

W. B. YEATS.March, 1908.

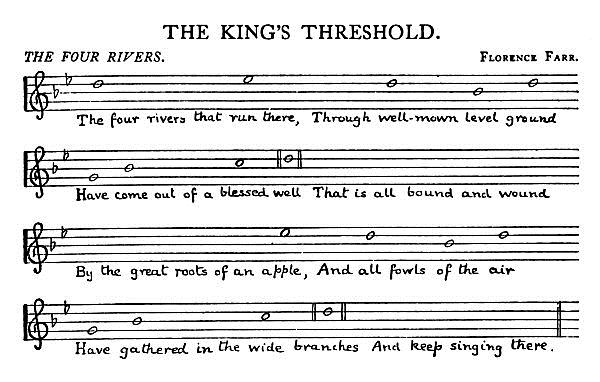

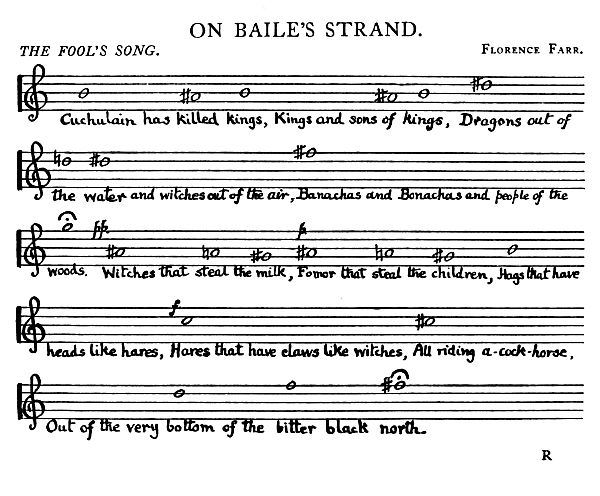

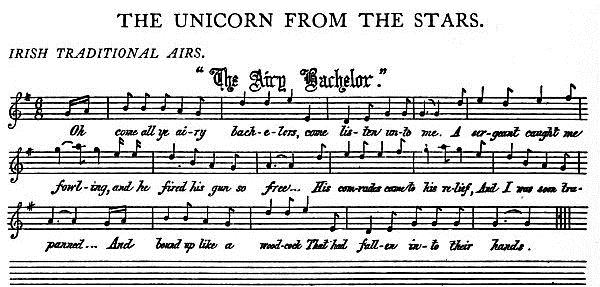

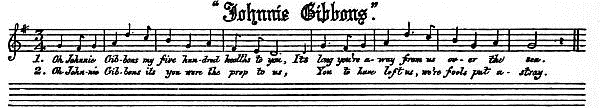

THE MUSIC FOR USE IN THE PERFORMANCE OF THESE PLAYS

All the music that is printed here, with the exception of Mr. Arthur Darley’s, is of that kind which I have described in Samhain and in Ideas of Good and Evil. Some of it is old Irish music made when all songs were but heightened speech, and some of it composed by modern musicians is none the less to be associated with words that must never lose the intonation of passionate speech. No vowel must ever be prolonged unnaturally, no word of mine must ever change into a mere musical note, no singer of my words must ever cease to be a man and become an instrument.

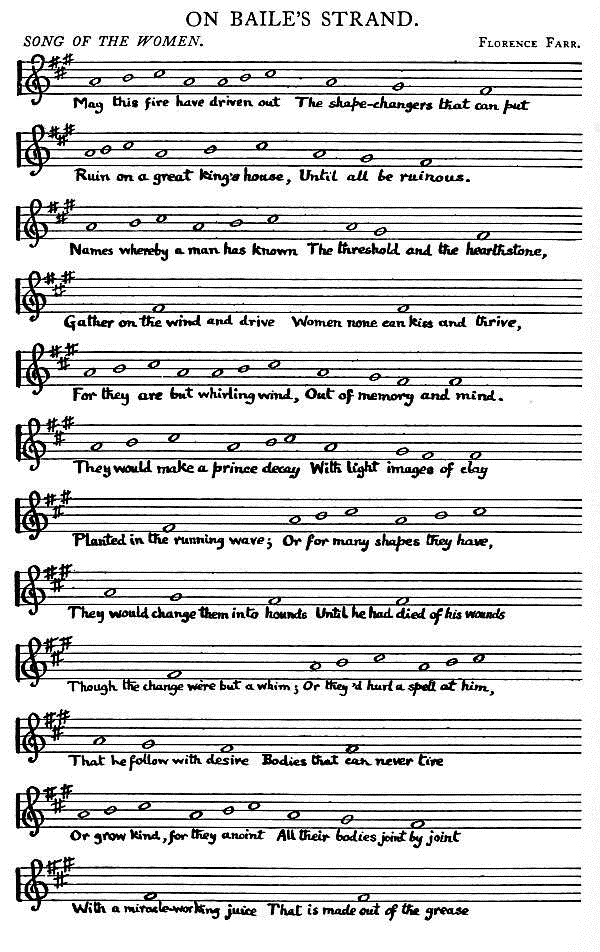

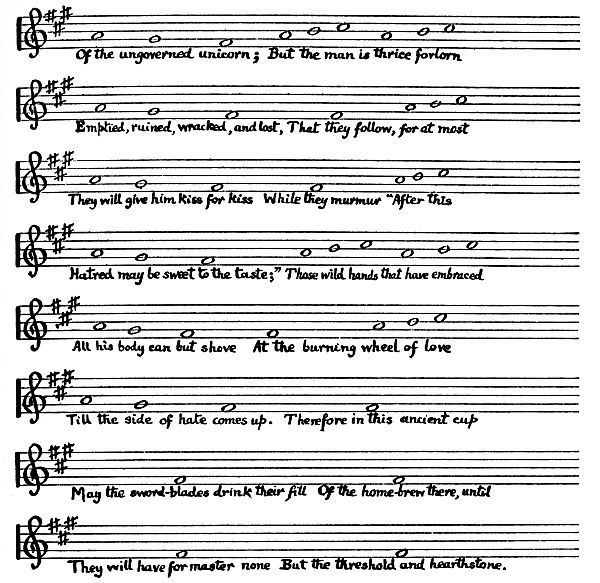

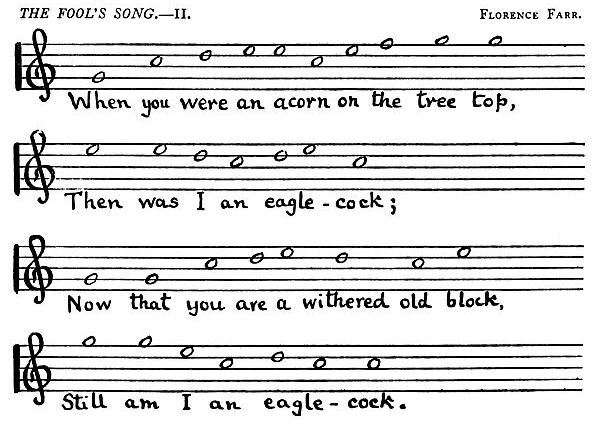

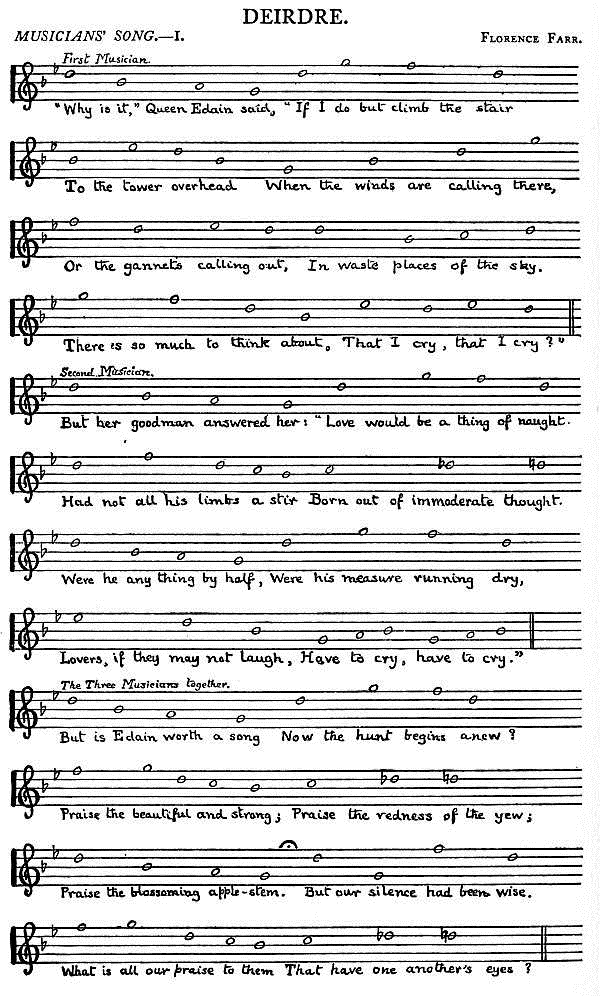

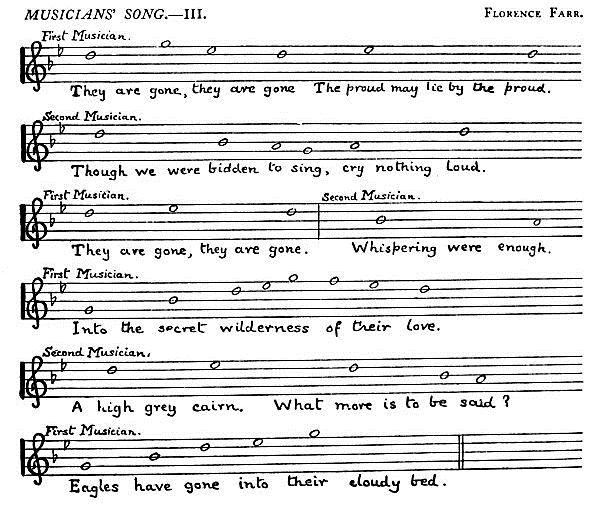

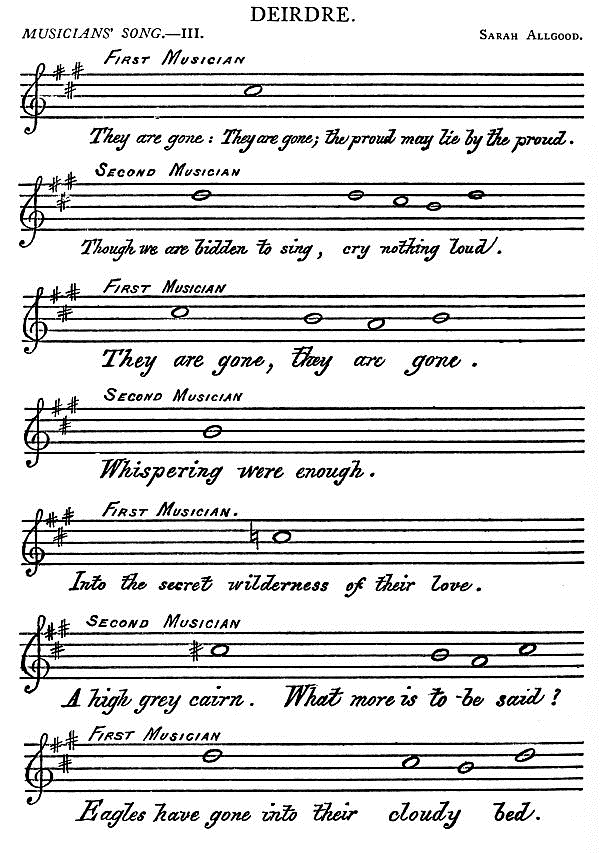

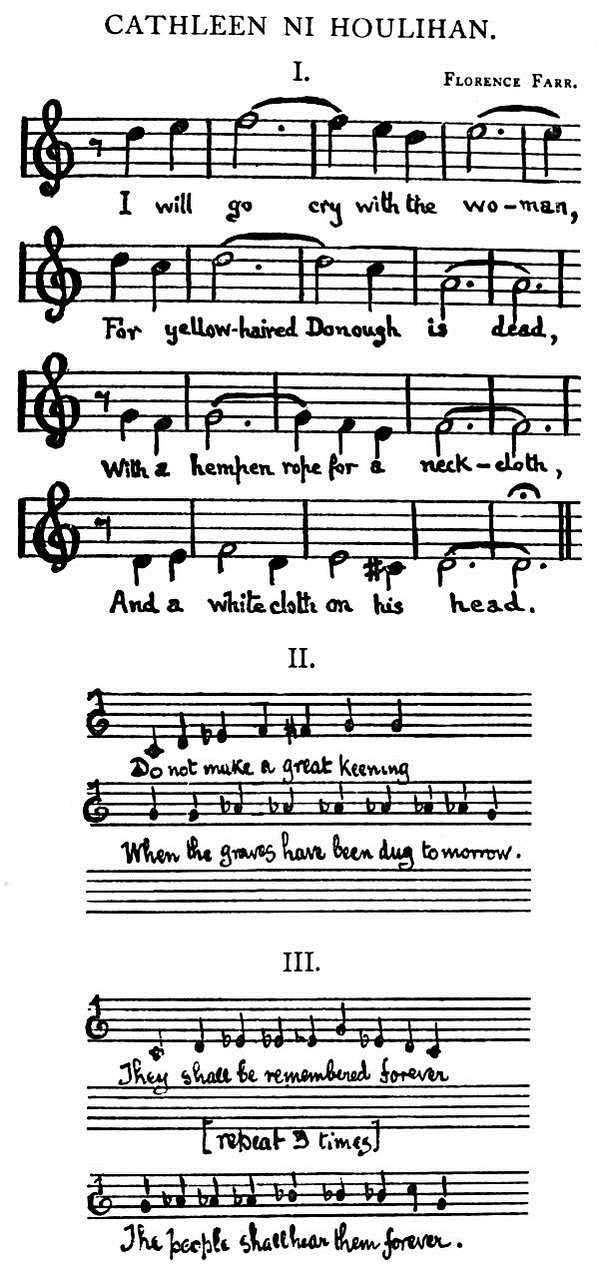

The degree of approach to ordinary singing depends on the context, for one desires a greater or lesser amount of contrast between the lyrics and the dialogue according to situation and emotion and the qualities of players. The words of Cathleen ni Houlihan about the ‘white-scarfed riders’ must be little more than regulated declamation; the little song of Leagerie when he seizes the ‘Golden Helmet’ should in its opening words be indistinguishable from the dialogue itself. Upon the other hand, Cathleen’s verses by the fire, and those of the pupils in the Hour-Glass, and those of the beggars in the Unicorn, are sung as the country people understand song. Modern singing would spoil them for dramatic purposes by taking the keenness and the salt out of the words. The songs in Deirdre, in Miss Farr’s and in Miss Allgood’s setting, need fine speakers of verse more than good singers; and in these, and still more in the song of the Three Women in Baile’s Strand, the singers must remember the natural speed of words. If the lyric in Baile’s Strand is sung slowly it is like church-singing, but if sung quickly and with the right expression it becomes an incantation so old that nobody can quite understand it. That it may give this sense of something half-forgotten, it must be sung with a certain lack of minute feeling for the meaning of the words, which, however, must always remain words. The songs in Deirdre, especially the last dirge, which is supposed to be the creation of the moment, must, upon the other hand, at any rate when Miss Farr’s or Miss Allgood’s music is used, be sung or spoken with minute passionate understanding. I have rehearsed the part of the Angel in the Hour-Glass with recorded notes throughout, and believe this is the right way; but in practice, owing to the difficulty of finding a player who did not sing too much the moment the notes were written down, have left it to the player’s own unrecorded inspiration, except at the ‘exit,’ where it is well for the player to go nearer to ordinary song.

I have not yet put Miss Farr’s Deirdre music to the test of performances, but, as she and I have worked out all this art of spoken song together, I have little doubt but I shall find it all I would have it. Mr. Darley’s music was used at the first production of the play and at its revival last spring, and was dramatically effective. I could hear the words perfectly, and I think they must have been audible to anyone hearing the play for the first or second time. They had not, however, the full animation of speech, as one heard it in the dirge at the end of the play set by Miss Allgood herself, who played the principal musician. It is very difficult for a musician who is not a speaker to do exactly what I want. Mr. Darley has written for singers not for speakers. His music is, perhaps, too elaborate, simple though it is. I have not had sufficient opportunity to experiment with the play to find out the exact distance from ordinary speech necessary in the first two lyrics, which must prolong the mood of the dialogue while being a rest from its passions. Miss Farr’s music will be used at the next revival of the play.

Mr. Darley’s music for Shadowy Waters was supposed to be played upon Forgael’s magic harp, and it accompanied words of Dectora’s and Aibric’s. It was played in reality upon a violin, always pizzicato, and gave the effect of harp playing, at any rate of a magic harp. The ‘cues’ are all given and the words are printed under the music. The violinist followed the voice, except in the case of the ‘O’, where it was the actress that had to follow.

W. B. YEATS.March, 1908.

THE KING’S THRESHOLD

ON BAILE’S STRAND. THE FOOL’S SONG

ON BAILE’S STRAND. – SONG OF THE WOMEN

THE FOOL’S SONG.– II

DEIRDRE. MUSICIANS’ SONG.– I

DEIRDRE. MUSICIANS’ SONG.– II

DEIRDRE. MUSICIANS’ SONG.– III. Farr

DEIRDRE. MUSICIANS’ SONG.– III. ALLGOOD

SHADOWY WATERS

THE UNICORN FROM THE STARS “The Airy Bachelor.”

THE UNICORN FROM THE STARS “Johnnie Gibbons.”

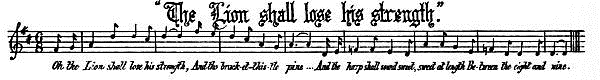

THE UNICORN FROM THE STARS “The Lion shall lose his strength.”

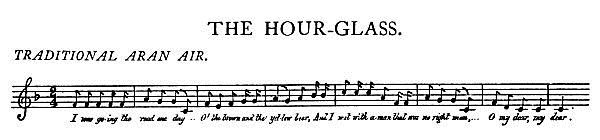

THE HOUR-GLASS

CATHLEEN NI HOULIHAN

MUSIC FOR LYRICS

Three of the following settings are by Miss Farr, and she accompanies the words upon her psaltery for the most part. She has a beautiful speaking-voice, and, an almost rarer thing, a perfect ear for verse; and nothing but the attempting of it will show how far these things can be taught or developed where they exist but a little. I believe that they should be a part of the teaching of all children, for the beauty of the speaking-voice is more important to our lives than that of the singing, and the rhythm of words comes more into the structure of our daily being than any abstract pattern of notes. The relation between formal music and speech will yet become the subject of science, not less than the occasion of artistic discovery; for I am certain that all poets, even all delighted readers of poetry, speak certain kinds of poetry to distinct and simple tunes, though the speakers may be, perhaps generally are, deaf to ordinary music, even what we call tone-deaf. I suggest that we will discover in this relation a very early stage in the development of music, with its own great beauty, and that those who love lyric poetry but cannot tell one tune from another repeat a state of mind which created music and yet was incapable of the emotional abstraction which delights in patterns of sound separated from words. To it the music was an unconscious creation, the words a conscious, for no beginnings are in the intellect, and no living thing remembers its own birth.

I give after Miss Farr’s settings three others, two taken down by Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch from myself, and one from a fine scholar in poetry, who hates all music but that of poetry, and knows of no instrument that does not fill him with rage and misery. Mr. Arnold Dolmetsch, when he took up the subject at my persuasion, wrote down the recitation of another lyric poet, who like myself knows nothing of music, and found little tunes that delighted him; and Mr. George Russell (‘A.E.’) writes all his lyrics, a musician tells me, to two little tunes which sound like old Arabic music. I do not mean that there is only one way of reciting a poem that is correct, for different tunes will fit different speakers or different moods of the same speaker, but as a rule the more the music of the verse becomes a movement of the stanza as a whole, at the same time detaching itself from the sense as in much of Mr. Swinburne’s poetry, the less does the poet vary in his recitation. I mean in the way he recites when alone, or unconscious of an audience, for before an audience he will remember the imperfection of his ear in note and tone, and cling to daily speech, or something like it.

Sometimes one composes to a remembered air. I wrote and I still speak the verses that begin ‘Autumn is over the long leaves that love us’ to some traditional air, though I could not tell that air or any other on another’s lips, and The Ballad of Father Gilligan to a modification of the air A Fine Old English Gentleman. When, however, the rhythm is more personal than it is in these simple verses, the tune will always be original and personal, alike in the poet and in the reader who has the right ear; and these tunes will now and again have great beauty.