полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Cicero. Volume II.

Had not Cicero too rejoiced at the uncle's murder? And having done so, was he not bound to endure the enmity he had provoked? He had not indeed killed Cæsar, or been aware that he was to be killed; but still it must be said of him that, having expressed his satisfaction at what had been done, he had identified himself with those who had killed him, and must share their fate. The slaying of a tyrant was almost by law enjoined upon Romans – was at any rate regarded as a virtue rather than a crime. There of course arises the question, who is to decide whether a man be a tyrant? and the idea being radically wrong, becomes enveloped in difficulty out of which there is no escape. But there remains as a fact the existence of the feeling which was at the time held to have justified Brutus – and also Cicero. A man has to inquire of his own heart with what amount of criminality he can accuse the Cicero of the day, or the young Augustus. Can any one say that Cicero was base to have rejoiced that Cæsar had been killed? Can any one not regard with horror the young Consul, as he sat there in the privacy of the island, with Antony on one side and Lepidus on the other, and then in the first days of his youth, with the down just coming on his cheeks, sending forth his edict for slaughtering the old friend of the Republic?

b. c. 43, ætat. 64.

It is supposed that Cicero left Rome in company with his brother Quintus, and that at first they went to Tusculum. There was no bar to their escaping from Italy had they so chosen, and probably such was their intention as soon as tidings reached them of the proscription. It is pleasant to think that they should again have become friends before they died. In truth, Marcus the elder was responsible for his brother's fate. Quintus had foreseen the sun rising in the political horizon, and had made his adorations accordingly. He, with others of his class, had shown himself ready to bow down before Cæsar. With his brother's assent he had become Cæsar's lieutenant in Gaul, such employment being in conformity with the practice of the Republic. When Cæsar had returned, and the question as to power arose at once between Cæsar and Pompey, Quintus, who had then been with his brother in Cilicia, was restrained by the influence of Marcus; but after Pharsalia the influence of Marcus was on the wane. We remember how young Quintus had broken away and had joined Cæsar's party. He had sunk so low that he had become "Antony's right hand." In that direction lay money, luxury, and all those good things which the government of the day had to offer. Cicero was so much in Cæsar's eyes, that Cæsar despised the elder and the younger Quintus for deserting their great relative, and would hardly have them. The influence of the brother and the uncle sat heavily on them. The shame of being Cæsarean while he was Pompeian, the shame of siding with Antony while he sided with the Republic, had been too great for them. While he was speaking his Philippics they could not but be enthusiastic on the same side. And now, when he was proscribed, they were both proscribed with him. As the story goes, Quintus returned from Tusculum to Rome to seek provision for their journey to Macedonia, there met his son, and they both died gallantly. Antony's hirelings came upon the two together, or nearly together, and, finding the son first, put him to the torture, so to learn from him the place of his father's concealment; then the father, hearing his son's screams, rushed out to his aid, and the two perished together. But this story also comes to us from Greek sources, and must be taken for what it is worth.

Marcus, alone in his litter, travelled through the country to his sea-side villa at Astura. Then he went on to Formiæ, sick with doubt, not knowing whether to stay and die, or encounter the winter sea in such boat as was provided for him. Should he seek the uncomfortable refuge of Brutus's army? We can remember his bitter exclamations as to the miseries of camp life. He did go on board; but was brought back by the winds, and his servants could not persuade him to make another attempt. Plutarch tells us that he was minded to go to Rome, to force his way into young Cæsar's house and there to stab himself, but that he was deterred from this melodramatic death by the fear of torture. The story only shows how great had been the attention given to every detail of his last moments, and what the people in Rome had learned to say of them. The same remark applies to Plutarch's tale as to the presuming crows who pecked at the cordage of his sails when his boat was turned to go back to the land, and afterward with their beaks strove to drag the bedclothes from off him when he lay waiting his fate the night before the murderers came to him.

He was being carried down from his villa at Formiæ to the sea-side when Antony's emissaries came upon him in his litter. There seem to have been two of them – both soldiers and officers in the pay of Antony – Popilius Lænas and Herennius. They overtook him in the wood, through which paths ran from the villa down to the sea-shore. On arriving at the house they had not found Cicero, but were put upon his track by a freedman who had belonged to Quintus, named Philologus. He could hardly have done a kinder act than to show the men the way how they might quickly release Cicero from his agony. They went down to the end of the wood, and there met the slaves bearing the litter. The men were willing to fight for their master; but Cicero, bidding them put down the chair, stretched out his neck and received his death-blow. Antony had given special orders to his servants. They were to bring Cicero's head and his hands – the hands which had written the Philippics, and the tongue which had spoken them – and his order was obeyed to the letter. Cicero was nearly sixty-four when he died, his birthday being on the 3d of January following. It would be hardly worth our while to delay ourselves for a moment with the horrors of Antony's canduct, and those of his wife Fulvia – Fulvia the widow of Clodius and the wife of Antony – were it not that we may see what were the manners to which a great Roman lady had descended in those days in which the Republic was brought to an end. On the rostra was stuck up the head and the hands as a spectacle to the people, while Fulvia specially avenged herself by piercing the tongue with her bodkin. That is the story of Cicero's death as it has been generally told.

We are told also that Rome heard the news and saw the sight with ill-suppressed lamentation. We can easily believe that it should have been so. I have endeavored, as I have gone on with my work, to compare him to an Englishman of the present day; but there is no comparing English eloquence to his, or the ravished ears of a Roman audience to the pleasure taken in listening to our great orators. The world has become too impatient for oratory, and then our Northern senses cannot appreciate the melody of sounds as did the finer organs of the Roman people. We require truth, and justice, and common-sense from those who address us, and get much more out of our public speeches than did the old Italians. We have taught ourselves to speak so that we may be believed – or have come near to it. A Roman audience did not much care, I fancy, whether the words spoken were true. But it was indispensable that they should be sweet – and sweet they always were. Sweet words were spoken to them, with their cadences all measured, with their rhythm all perfect; but no words had ever been so sweet as those of Cicero. I even, with my obtuse ears, can find myself sometimes lifted by them into a world of melody, little as I know of their pronunciation and their tone. And with the upper classes – those who read, his literature had become almost as divine as his speech. He had come to be the one man who could express himself in perfect language. As in the next age the Eclogues of Virgil and the Odes of Horace became dear to all the educated classes because of the charm of their expression, so in their time, I fancy, had become the language of Cicero. It is not surprising that men should have wept when they saw that ghaatly face staring at them from the rostra, and the protruding tongue and the outstretched hands. The marvel is that, seeing it, they should still have borne with Antony.

That which Cicero has produced in literature is, as a rule, admitted to be excellent; but his character as a man has been held to be tarnished by three faults – dishonesty, cowardice, and insincerity. As to the first, I have denied it altogether, and my denial is now submitted to the reader for his judgment It seems to have been brought against him not in order to make him appear guilty, but because it bas appeared to be impossible that, when others were so deeply in fault, he should have been innocent. That he should have asked for nothing, that he should have taken no illicit rewards, that he should not have submitted to be feed, but that he should have kept his hands clean while all around him were grasping at everything – taking money, selling their aid for stipulated payments, grinding miserable creditors has been too much for believe. I will not take my readers back over the cases brought against him, but will ask them to ask themselves whether there is one supported by evidence fit to go before a jury. The accusations have been made by men clean-handed themselves; but to them it has appeared unreasonable to believe that a Roman oligarch of those days should be an honest gentleman.

As to his cowardice, I feel more doubt as to my power of carrying my readers with me, though no doubt as to Cicero's courage. Cowardice in a man is abominable. But what is cowardice? and what courage? It is a matter in which so many errors are made! Tinsel is so apt to shine like gold and dazzle the sight! In one of the earlier chapters of this book, when speaking of Catiline, I have referred to the remarks of a contemporary writer: "The world has generally a generous word for the memory of a brave man dying for his cause!" "All wounded in front," is quoted by this author from Sallust. "Not a man taken alive! Catiline himself gasping out his life ringed around with corpses of his friends." That is given as a picture of a brave man dying for his cause, who should excite our admiration even though his cause were bad. In the previous lines we have an intended portrait of Cicero, who, "thinking, no doubt, that he had done a good day's work for his patrons, declined to run himself into more danger." Here is one story told of courage, and another of fear. Let us pause for a moment and regard the facts. Catiline, when hunted to the last gasp, faced his enemy and died fighting like a man – or a bull. Who is there cannot do so much as that? For a shilling or eighteen-pence a day we can get an army of brave men who will face an enemy – and die, if death should come. It is not a great thing, nor a rare, for a man in battle not to run away. With regard to Cicero the allegation is that he would not be allowed to be bribed to accuse Cæsar, and thus incur danger. The accusation which is thus brought against him is borrowed from Sallust, and is no doubt false; but I take it in the spirit in which it is made. Cicero feared to accuse Cæsar, lest he should find himself enveloped, through Cæsar's means, in fresh danger. Grant that he did so. Was he wrong at such a moment to save his life for the Republic – and for himself? His object was to banish Catiline, and not to catch in his net every existing conspirator. He could stop the conspiracy by securing a few, and might drive many into arms by endeavoring to encircle all. Was this cowardice? During all those days he had to live with his life in his hands, passing about among conspirators who he knew were sworn to kill him, and in the midst of his danger he could walk and talk and think like a man. It was the same when he went down into the court to plead for Milo, with the gladiators of Clodius and the soldiery of Pompey equally adverse to him. It was the same when he uttered Philippic after Philippic in the presence of Antony's friends. True courage, to my thinking, consists not in facing an unavoidable danger. Any man worthy of the name can do that. The felon that will be hung to-morrow shall walk up to the scaffold and seem ready to surrender the life he cannot save. But he who, with the blood running hot through his veins, with a full desire of life at his heart, with high aspirations as to the future, with everything around him to make him happy – love and friendship and pleasant work – when he can willingly imperil all because duty requires it, he is brave. Of such a nature was Cicero's courage.

As to the third charge – that of insincerity – I would ask of my readers to bethink themselves how few men are sincere now? How near have we approached to the beauty of truth, with all Christ's teaching to guide us? Not by any means close, though we are nearer to it than the Romans were in Cicero's days. At any rate we have learned to love it dearly, though we may not practise it entirely. He also had learned to love it, but not yet to practise it quite so well as we do. When it shall be said of men truly that they are thoroughly sincere, then the millennium will have come. We flatter, and love to be flattered. Cicero flattered men, and loved it better. We are fond of praise, and all but ask for it. Cicero was fond of it, and did ask for it. But when truth was demanded from him, truth was there.

Was Cicero sincere to his party, was he sincere to his friends, was he sincere to his family, was he sincere to his dependents? Did he offer to help and not help? Did he ever desert his ship, when he had engaged himself to serve? I think not. He would ask one man to praise him to another – and that is not sincere. He would apply for eulogy to the historian of his day – and that is not sincere. He would speak ill or well of a man before the judge, according as he was his client or his adversary – and that perhaps is not sincere. But I know few in history on whose positive sincerity in a cause his adherents could rest with greater security. Look at his whole life with Pompey – as to which we see his little insincerities of the moment because we have his letters to Atticus; but he was true to his political idea of a Pompey long after that Pompey had faded from his dreams. For twenty years we have every thought of his heart; and because the feelings of one moment vary from those of another, we call him insincere. What if we had Pompey's thoughts and Cæsar's, would they be less so? Could Cæsar have told us all his feelings? Cicero was insincere: I cannot say otherwise. But he was so much more sincere than other Romans as to make me feel that, when writing his life, I have been dealing with the character of one who might have been a modern gentleman.

Chapter XI

CICERO'S RHETORIC

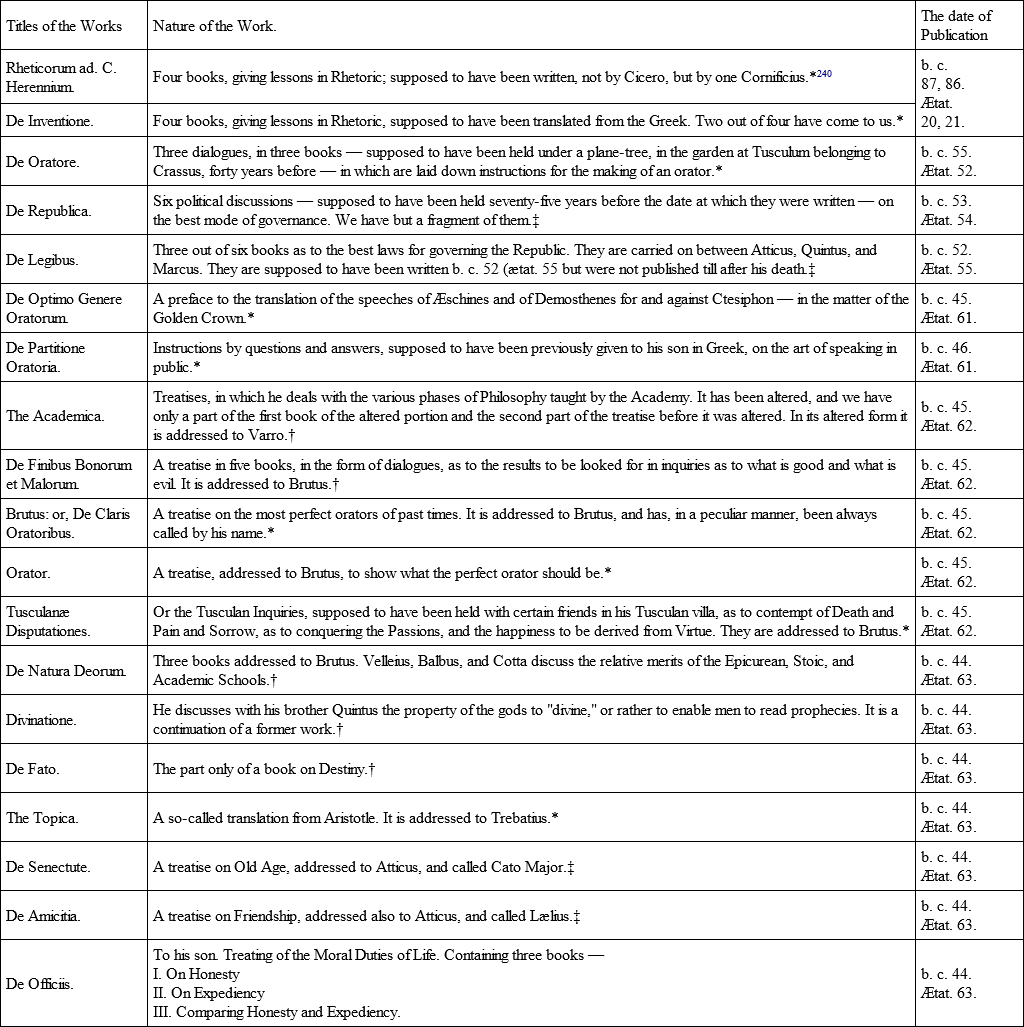

It is well known that Cicero's works are divided into four main parts. There are the Rhetoric, the Orations, the Epistles, and the Philosophy. There is a fifth part, indeed – the Poetry; but of that there is not much, and of the little we have but little is esteemed. There are not many, I fear, who think that Cicero has deserved well of his country by his poetry. His prose works have been divided as I have stated them. Of these, two portions have been dealt with already – as far as I am able to deal with them. Of the Orations and Epistles I have spoken as I have gone on with my task, because the matter there treated has been available for the purposes of biography: the other two, the Rhetoric and the Philosophy, have been distinct from the author's life.239 They might have been good or bad, and his life would have been still the same; therefore it is necessary to divide them from his life, and to speak of them separately. They are the work of his silent chamber, as the others were the enthusiastic outpourings of his daily spirit, or the elaborated arguments of his public career. Who has left behind him so widely spread a breadth of literature? Who has made so many efforts, and has so well succeeded in them all? I do not know that it has ever been given to any one man to run up and down the strings of knowledge, and touch them all as though each had been his peculiar study, as Cicero has done.

His rhetoric has been always made to come first, because, upon the whole, it was first written. It may be as well here to give a list of his main works, with their dates – premising, however, that we by no means in that way get over the difficulty as to time, even in cases as to which we are sure of our facts. A treatise may have been commenced and then put by, or may have been written some time previously to publication. Or it may be, as were those which are called the Academica, that it was remodelled, and altered in its shape and form. The Academica were written at the instance of Atticus. We now have the altered edition of a fragment of the first book, and the original of the second book. In this manner there have come discrepancies which nearly break the heart of him who would fain make his list clear. But here, on the whole, is presented to the reader with fair accuracy a list of the works of Cicero, independent of that continual but ever-changing current of his thought which came welling out from him daily in his speeches and his letters. Again, however, we must remember that here are omitted all those which are either wholly lost or have come to us only in fragments too abruptly broken for the purposes of continuous study. Of these I will not even attempt to give the names, though when we remember some of the subjects – the De Gloria, the De Re Militari – he could not go into the army for a month or two without writing a book about it – the De Auguriis, the De Philosophia, the De Suis Temporibus, the De Suis Consiliis, the De Jure Civili, and the De Universo, we may well ask ourselves what were the subjects on which he did not write. In addition to these, much that has come to us has been extracted, as it were unwillingly, from palimpsests, and is, from that and from other causes, fragmentary. We have indeed only fragments of the essays De Republica, De Legibus, De Natura Deorum, De Divinatione, and De Fato, in addition to the Academica.

The list of the works of which it is my purpose to give some shortest possible account in the following chapters is as follows:

Примечание 1240

It is to be observed from this list that for thirty years of his life Cicero was silent in regard to literature – for those thirty years in which the best fruits of a man's exertion are expected from him. Indeed, we may say that for the first fifty-two years of his life he wrote nothing but letters and speeches. Of the two treatises with which the list is headed, the first, in all probability, did not come from his pen, and the second is no more than a lad's translation from a Greek author. As to the work of translation, it must be understood that the Greek and Latin languages did not stand in reference to each other as they do now to modern readers. We translate in order that the pearls hidden under a foreign language may be conveyed to those who do not read it, and admit, when we are so concerned, that none can truly drink the fresh water from a fountain so handled. The Romans, in translating from the Greek, thinking nothing of literary excellence, felt that they were bringing Greek thought into a form of language in which it could be thus made useful. There was no value for the words, but only for the thing to be found in it. Thence it has come that no acknowledgment is made. We moderns confess that we are translating, and hardly assume for ourselves a third-rate literary place. When, on the other hand, we find the unexpressed thought floating about the world, we take it, and we make it our own when we put it into a book. The originality is regarded as being in the language, not in the thought. But to the Roman, when he found the thought floating about the world in the Greek character, it was free for him to adopt it and to make it his own. Cicero, had he done in these days with this treatise as I have suggested, would have been guilty of gross plagiarism, but there was nothing of the kind known then. This must be continually remembered in reading his essays. You will find large portions of them taken from the Greek without acknowledgment. Often it shall be so, because it suits him to contradict an assertion or to show that it has been allowed to lead to false conclusions. This general liberty of translation has been so frequently taken by the Latin poets – by Virgil and Horace, let us say, as being those best known – that they have been regarded by some as no more than translations. To them to have been translators of Homer, or of Pindar and Stesichorus, and to have put into Latin language ideas which were noble, was a work as worthy of praise as that of inventing. And it must be added that the forms they have used have been perfect in their kind. There has been no need to them for close translation. They have found the idea, and their object has been to present it to their readers in the best possible language. He who has worked amid the bonds of modern translation well knows how different it has been with him. There is not much in the treatise De Inventione to arrest us. We should say, from reading it, that the matter it contains is too good for the production of a youth of twenty-one, but that the language in which it is written is not peculiarly fine. The writer intended to continue it – or wrote as though he did – and therefore we may imagine that it has come to us from some larger source. It is full of standing cases, or examples of the law courts, which are brought up to show the way in which these things are handled. We can imagine that a Roman youth should be practised in such matters, but we cannot imagine that the same youth should have thought of them all, and remembered them all, and should have been able to describe them.

The following is an example: "A certain man on his journey encountered a traveller going to make a purchase, having with him a sum of money. They chatted along the road together, and, as happens on such occasions, they became intimate. They went to the same inn, where they supped, and said that they would sleep together. Having supped they went to bed; when the landlord – for this was told after it had all been found out, and he had been taken for another offence – having perceived that one man had money, in the middle of the night, knowing how sound they would sleep from fatigue, crept up to them, and having taken out of its scabbard the sword of him that was without the money as it lay by his side, he killed the other man, put back the sword, and then went to his bed. But he whose sword had been used rose long before daylight and called loudly to his companion. Finding that the man slumbered too heavily to be stirred, he took himself and his sword and the other things he had brought away with him and started alone. But the landlord soon raised the hue-and-cry, 'A man has been killed!' and, with some of the guests, followed him who had gone off. They took the man on the road, and dragged his sword out of its sheath, which they found all bloody. They carried him back to the city, and he was accused." In this cause there is the declaration of the crime alleged, "You killed the man." There is the defence, "I did not kill him." Thence arises the issue. The question to be judged is one of conjecture. "Did he kill him?"241 We may judge from the story that the case was not one which had occurred in life, but had been made up. The truculent landlord creeping in and finding that everything was as he wished it; and the moneyless man going off in the dark, leaving his dead bedfellow behind him – as the landlord had intended that he should – form all the incidents of a stock piece for rehearsal rather than the occurrence of a true murder. The same may be said of other examples adduced, here as afterward, by Quintilian. They are well-known cases, and had probably been handed down from one student to another. They tell us more of the manners of the people than of the rudiments of their law.

From this may be seen the nature of the work. From thence we skip over thirty years and come at once to b. c. 55. The days of the Triumvirate had come, and the quarrel with Clodius – of Cicero's exile and his return, together with the speeches which he had made, in the agony of his anger, against his enemies. And all this had taken place since those halcyon days in which he had risen, on the voices of his countrymen, to be Quæstor, Ædile, Prætor, and Consul. He had first succeeded as a public man, and then, having been found too honest, he had failed. There can be no doubt that he had failed because he had been too honest. I must have told the story of his political life badly if I have not shown that Cæsar had retired from the assault because Cicero was Consul, but had retired only as a man does who steps back in order that his next spring forward may be made with more avail. He chose well the time for his next attack, and Cicero was driven to decide between three things – he must be Cæsarean, or must be quiet, or he must go. He would not be Cæsarean, he certainly could not be quiet, and he went. The immediate effect of his banishment was on him so great that he could not employ himself. But he returned to Rome, and, with too evident a reliance on a short-lived popularity, he endeavored to replace himself in men's eyes; but it must have been clear to him that he had struggled in vain. Then he looked back upon his art, his oratory, and told himself that, as the life of a man of action was no longer open to him, he could make for himself a greater career as a man of letters. He could do so. He has done so. But I doubt whether he had ever a confirmed purpose as to the future. Had some grand Consular career been open to him – had it been given to him to do by means of the law what Cæsar did by ignoring the law – this life of him would not have been written. There would, at any rate, have been no need of these last chapters to show how indomitable was the energy and how excellent the skill of him who could write such books, because – he had nothing else to do.