полная версия

полная версияTypes of Naval Officers, Drawn from the History of the British Navy

Considered simply as a tactical situation, or problem, quite independent of any tactical forethought or insight on the part of the commander-in-chief,—of which there is little indication,—the conditions resulting from his attack were well summed up in a contemporary publication, wholly adverse to Mathews in tone, and saturated with the professional prepossessions embodied in the Fighting Instructions. This writer, who claims to be a naval officer, says:

"The whole amount of this fight is that the centre, consisting of eleven ships-of-the-line, together with two of-the-line and two fifty-gun ships of the Rear-Admiral's division [the van], were able to destroy the whole Spanish squadron, much more so as three of those ships went on with the French [the allied van], and four of the sternmost did not get up with their admiral before it was darkish, long after the fire-ship's misfortune, so that the whole afternoon there were only five, out of which the Constante was beat away in less than an hour; what then fifteen ships could be doing from half an hour past one till past five, no less than four hours, and these ships not taken, burnt, and destroyed, is the question which behooves them to answer."

In brief, then, Mathews's attack was so delivered that the weight of thirteen of-the-line fell upon five Spanish of the same class, the discomfiture of which, actually accomplished even under the misbehavior of several British ships, separated the extreme rear, five other Spanish vessels, from the rest of the allies. Whatever the personal merit or lack of merit on the part of the commander-in-chief, such an opportunity, pushed home by a "band of brothers," would at the least have wiped out these rear ten ships of the allies; nor could the remainder in the van have redeemed the situation. As for the method of attack, it is worthy of note that, although adopted by Mathews accidentally, it anticipated, not only the best general practice of a later date, but specifically the purpose of Rodney in the action which he himself considered the most meritorious of his whole career,—that of April 17, 1780. The decisive signal given by him on that occasion, as explained by himself, meant that each ship should steer, not for the ship corresponding numerically to her in the enemy's order, but for the one immediately opposite at the time the signal was made. This is what Mathews and his seconds did, and others should have imitated. Singularly enough, not only was the opportunity thus created lost, but there is no trace of its existence, even, being appreciated in such wise as to affect professional opinion. As far as Mathews himself was concerned, the accounts show that his conduct, instead of indicating tactical sagacity, was a mere counsel of desperation.

But after engaging he committed palpable and even discreditable mistakes. Hauling to windward—away—when the Marlborough forced him ahead, abandoned that ship to overwhelming numbers, and countenanced the irresolution of the Dorsetshire and others. Continuing to stand north, after wearing on the evening of the battle, was virtually a retreat, unjustified by the conditions; and it would seem that the same false step gravely imperilled the Berwick, Hawke holding on, most properly, to the very last moment of safety, in order to get back his prize-crew. Bringing-to on the night of the 23d was an error of the same character as standing north during that of the 22d. It was the act of a doubtful, irresolute man,—irresolute, not because a coward, but because wanting in the self-confidence that springs from conscious professional competency. In short, the commander-in-chief's unfitness was graphically portrayed in the conversation with Cornwall from the quarter gallery of the flag-ship. "If you approve and will go down with me, I will go down." Like so many men, he needed a backer, to settle his doubts and to stiffen his backbone. The instance is far from unique.

In the case of Byng, as of Mathews, we are not concerned with the general considerations of the campaign to which the battle was incidental. It is sufficient to note that in Minorca, then a British possession, the French had landed an army of 15,000 men, with siege artillery sufficient to reduce the principal port and fortress, Port Mahon; upon which the whole island must fall. Their communications with France depended upon the French fleet cruising in the neighborhood. Serious injury inflicted upon it would therefore go far to relieve the invested garrison.

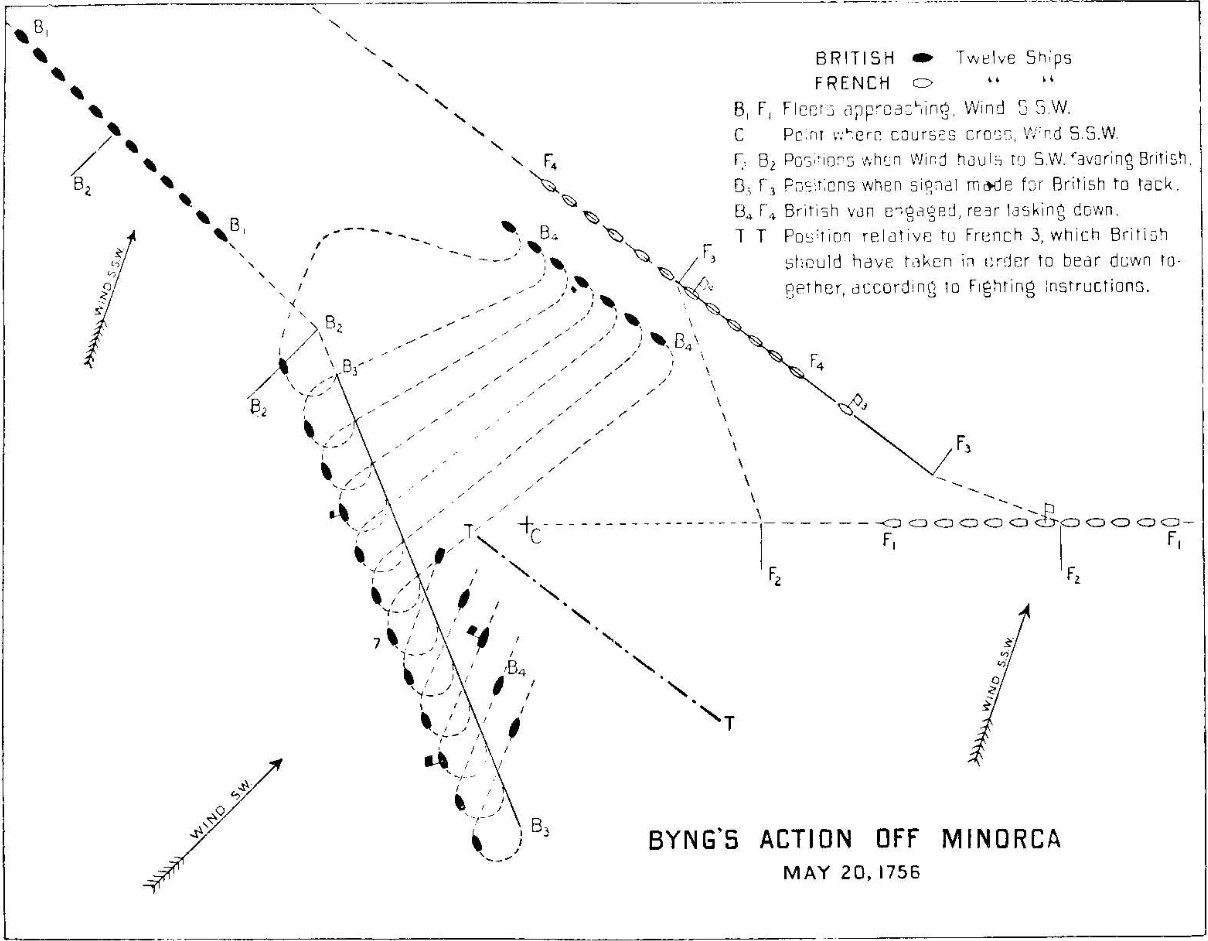

Under these circumstances the British fleet sighted Minorca on the 19th of May, 1756, and was attempting to exchange information with the besieged, when the French fleet was seen in the southeast. Byng stood towards it, abandoning for the time the effort to communicate. That night both fleets manoeuvred for advantage of position with regard to the wind. The next day, between 9 and 10 A.M., they came again in view of each other, and at 11 were about six miles apart, the French still to the southeast, with a breeze at south-southwest to southwest. The British once more advanced towards them, close hauled on the starboard tack, heading southeasterly, the enemy standing on the opposite tack, heading westerly, both carrying sail to secure the weather gage (B1, F1). It appeared at first that the French would pass ahead of the British, retaining the windward position; but towards noon the wind changed, enabling the latter to lie up a point or two higher (B2). This also forced the bows of the several French vessels off their course, and put them out of a regular line of battle; that is, they could no longer sail in each other's wake (F2). Being thus disordered, they reformed on the same tack, heading northwest, with the wind very little forward of the beam. This not only took time, but lost ground to leeward, because the quickest way to re-establish the order was for the mass of the fleet to take their new positions from the leewardmost vessel. When formed (F3), as they could not now prevent the British line from passing ahead, they hove-to with their main-topsails aback,—stopped,—awaiting the attack, which was thenceforth inevitable and close at hand.

Plan of Byng's Action off Minorca, May 20, 1756

In consequence of what has been stated, the British line (B2-B3)—more properly, column—was passing ahead of the French (F2-F3), steering towards their rear, in a direction in a general sense opposite to theirs, but not parallel; that is, the British course made an angle, of between thirty and forty-five degrees, with the line on which their enemy was ranged. Hence, barring orders to the contrary,—which were not given,—each British ship was at its nearest to the enemy as she passed their van, and became more and more distant as she drew to the rear. It would have been impossible to realize more exactly the postulate of the 17th Article of the Fighting Instructions, which in itself voiced the ideal conditions of an advantageous naval position for attack, as conceived by the average officer of the day; and, as though most effectually to demonstrate once for all how that sort of thing would work, the adjunct circumstances approached perfection. The admiral was thoroughly wedded to the old system, without an idea of departing from it, and there was a fair working breeze with which to give it effect, for the ships under topsails and foresail would go about three knots; with top-gallant sails, perhaps over four. A fifty-gun ship, about the middle of the engagement, had to close her lower deck ports when she set her top-gallant sails on the wind, which had then freshened a little.

The 17th Article read thus: "If the admiral see the enemy standing towards him, and he has the wind of them, the van of the fleet is to make sail till they come the length of the enemy's rear, and our rear abreast of the enemy's van; then he that is in the rear of our fleet is to tack first, and every ship one after another as fast as they can throughout the whole line; and if the admiral will have the whole fleet to tack together, the sooner to put them in a posture of engaging the enemy, he will hoist" a prescribed signal, "and fire a gun; and whilst they are in fight with the enemy the ships will keep at half a cable's length—one hundred yards—one of the other." All this Byng aimed to do. The conditions exactly fitted, and he exactly followed the rules, with one or two slight exceptions, which will appear, and for which the Court duly censured him.

When thus much had been done, the 19th Article in turn found its postulate realized, and laid down its corresponding instruction: "If the admiral and his fleet have the wind of the enemy, and they have stretched themselves in a line of battle, the van of the admiral's fleet is to steer with the van of the enemy's, and there to engage with them." The precise force of "steer with" is not immediately apparent to us to-day, nor does it seem to have been perfectly clear then; for the question was put to the captain of the flag-ship,—the heroic Gardiner,—"You have been asked if the admiral did not express some uneasiness at Captain Andrews"—of the van ship in the action—"not seeming to understand the 19th Article of the Fighting Instructions; Do not you understand that article to relate to our van particularly when the two fleets are [already] in a parallel line of battle to each other?" (As TT, F3). Answer: "I apprehended it in the situation" [not parallel] "we were in1 if the word For were instead of the word With, he would, I apprehend, have steered directly for the van ship of the Enemy." Question. "As the 19th Article expresses to steer with the van of the enemy, if the leading ship had done so, in the oblique line we were in with the enemy, and every ship had observed it the same, would it not have prevented our rear coming to action at all, at least within a proper distance?" Answer: "Rear, and van too." "Steer with" therefore meant, to the Court and to Gardiner, to steer parallel to the enemy,—possibly likewise abreast,—and if the fleets were already parallel the instruction would work; but neither the articles themselves, nor Byng by his signals, did anything to effect parallelism before making the signal to engage.

The captain of the ship sternmost in passing, which became the van when the fleet tacked together according to the Instructions and signals, evidently shared Gardiner's impression; when about, he steered parallel to—"with"—the French, who had the wind nearly abeam. The mischief was that the ships ahead of him in passing were successively more and more distant from the enemy, and if they too, after tacking, steered with the latter, they would never get any nearer. The impasse is clear. Other measures doubtless would enable an admiral to range his fleet parallel to the enemy at any chosen distance, by taking a position himself and forming the fleet on his ship; or, in this particular instance, Byng being with the van as it, on the starboard tack, was passing the enemy (B3 B3), could at any moment have brought his fleet parallel to the French by signalling the then van ship to keep away a certain amount, the rest following in her wake. Nothing to that effect being in the Instructions, it seems not to have occurred to him. His one idea was to conform to them, and he apprehended that after tacking, as they prescribed, the new van ship would bear down and engage without further orders, keeping parallel to the French when within point-blank, the others following her as they could; a process which, from the varying distances, would expose each to a concentrated fire as they successively approached. Byng's action is only explicable to the writer by supposing that he thus by "steer with" understood "steer for;" for when, after the fleet tacked together, the new van ship (formerly the rear) did not of her own motion head for the leading enemy, he signalled her to steer one point, and then two points, in that direction. This, he explained in his defence, was "to put the leading captain in mind of his Instructions, who I perceived did not steer away with the enemy's leading ship agreeable to the 19th Article of the Fighting Instructions." The results of these orders not answering his expectations, he then made the signal to engage, as the only remaining way perceptible to him for carrying out the Instructions.

To summarize the foregoing, up to the moment the signal for battle was made: While the fleets were striving for the weather gage, the wind had shifted to the southwest. The French, momentarily disordered by the change, had formed in line ahead about noon, heading northwest, westerly, so as just to keep their main topsails aback and the ships with bare steerage way, but under command (F3). The British standing south-southeast, by the wind, were passing (B2-B3) across the head of the enemy's fleet at a distance of from three to two miles—the latter being the estimate by their ships then in the rear. The French having twelve vessels in line and the British thirteen, the gradual progress of the latter should bring their then van "the length of the enemy's rear," about the time the rear came abreast of his van. When this happened, the Instructions required that the fleet tack together, and then stand for the enemy, ship to ship, number one to number one, and so along the line till the number twelves met2.

This Byng purposed to do, but, unluckily for himself, ventured on a refinement. Considering that, if his vessels bore down when abreast their respective antagonists, they would go bows-on, perpendicularly, subject to a raking—enfilading—fire, he deferred the signal to tack till his van had passed some distance beyond the French rear, because thus they would have to approach in a slanting direction. He left out of his account here the fact that all long columns tend to straggle in the rear; hence, although he waited till his three or four leading ships had passed the enemy before making signal to tack, the rear had got no farther than abreast the hostile van. Two of the clearest witnesses, Baird of the Portland, next to the then rear ship, and Cornwall of the Revenge, seventh from it, testified that, after tacking together, to the port tack, when they kept away for the enemy in obedience to the signal for battle, it was necessary, in order to reach their particular opponents, to bring the wind not only as far as astern, but on the starboard quarter, showing that they had been in rear of their station before tacking, and so too far ahead after it; while Durell of the Trident, ninth from rear and therefore fifth from van, asserted that at the same moment the British van, which after tacking became the rear, had overpassed the enemy by five or six ships. This may be an exaggeration, but that three or four vessels had gone beyond is proved by evidence from the ships at that end of the line.

The Court therefore distinctly censured the admiral for this novelty: "Unanimously, the Court are of opinion that when the British fleet on the starboard tack were stretched abreast, or about the beam of the enemy's line, the admiral should have tacked the fleet all together, and immediately have conducted it on a direct course for the enemy, the van steering for the enemy's van," etc. The instructive point, however, is not Byng's variation, nor the Court's censure, but the idea, common to both, that the one and only way to use your dozen ships under the conditions was to send each against a separate antagonist. The highest and authoritative conception of a fleet action was thus a dozen naval duels, occurring simultaneously, under initial conditions unfavorable to the assailant. It is almost needless to remark that this is as contrary to universal military teaching as it was to the practice of Rodney, Howe, Jervis, and Nelson, a generation or two later.

This is, in fact, the chief significance of this action, which ratified and in a measure closed the effete system to which the middle eighteenth century had degraded the erroneous, but comparatively hearty, tradition received by it from the seventeenth. It is true, the same blundering method was illustrated in the War of 1778. Arbuthnot and Graves, captains when Byng was tried, followed his plan in 1781, with like demonstration of practical disaster attending false theory; but, while the tactical inefficiency was little less, the evidence of faint-hearted professional incompetency, of utter personal inadequacy, was at least not so glaring. It is the combination of the two in the person of the same commander that has given to this action its pitiful pre-eminence in the naval annals of the century.

It is, therefore, not so much to point out the lesson, as to reinforce its teaching by the exemplification of the practical results, that there is advantage in tracing the sequel of events in this battle. The signal to tack was made when the British van had reached beyond the enemy's rear, at a very little after 1 P.M. (B3). This reversed the line of battle, the rear becoming the van, on the port tack. When done, the new van was about two miles from that of the French (F4); the new rear, in which Byng was fourth from sternmost, was three and a half or four from their rear. Between this and 2 P.M. came the signals for the ship then leading to keep two points, twenty-five degrees, more to starboard,—towards the enemy; a measure which could only have the bad effect of increasing the angle which the British line already made with that of the French, and the consequent inequality of distance to be traversed by their vessels in reaching their opponents. At 2.20 the signal for battle was made, and was repeated by the second in command, Rear-Admiral Temple West, who was in the fourth ship from the van. His division of six bore up at once and ran straight down before the wind, under topsails only, for their several antagonists; the sole exception being the van-most vessel, which took the slanting direction desired by Byng, with the consequence that she got ahead of her position, had to back and to wear to regain it, and was worse punished than any of her comrades. The others engaged in line, within point-blank, the rear-admiral hoisting the flag for close action (B4). Fifteen minutes later, the sixth ship, and rearmost of the van, the Intrepid, lost her foretopmast, which crippled her.

The seventh ship, which was the leader of the rear, Byng's own division, got out of his hands before he could hold her. Her captain, Frederick Cornwall, was nephew to the gallant fellow who fell backing Mathews so nobly off Toulon, and had then succeeded to the command of the Marlborough, fighting her till himself disabled. He had to bring the wind on the starboard quarter of his little sixty-four, in order to reach the seventh in the enemy's line, which was an eighty-gun ship, carrying the flag of the French admiral. This post, by professional etiquette, as by evident military considerations, Byng owed to his own flag-ship, of equal force.

The rest of the rear division the commander-in-chief attempted to carry with himself, slanting down; or, as the naval term then had it, "lasking" towards the enemy. The flag-ship kept away four points—forty-five degrees; but hardly had she started, under the very moderate canvas of topsails and foresail, to cover the much greater distance to be travelled, in order to support the van by engaging the enemy's rear, when Byng observed that the two ships on his left—towards the van—were not keeping pace with him. He ordered the main and mizzen topsails to be backed to wait for them. Gardiner, the captain, "took the liberty of offering the opinion" that, if sail were increased instead of reduced, the ships concerned would take the hint, that they would all be sooner alongside the enemy, and probably receive less damage in going down. It was a question of example. The admiral replied, "You see that the signal for the line is out, and I am ahead of those two ships; and you would not have me, as admiral of the fleet, run down as if I was going to engage a single ship. It was Mr. Mathews's misfortune to be prejudiced by not carrying his force down together, which I shall endeavor to avoid." Gardiner again "took the liberty" of saying he would answer for one of the two captains doing his duty. The incident, up to the ship gathering way again, occupied less than ten minutes; but with the van going down headlong—as it ought—one ceases to wonder at the impression on the public produced by one who preferred lagging for laggards to hastening to support the forward, and that the populace suspected something worse than pedantry in such reasoning at such a moment. When way was resumed, it was again under the very leisurely canvas of topsails and foresail.

By this had occurred the incident of the Intrepid losing her foretopmast. It was an ordinary casualty of battle, and one to be expected; but to such a temper as Byng's, and under the cast-iron regulations of the Instructions, it entailed consequences fatal to success in the action,—if success were ever attainable under such a method,—and was ultimately fatal to the admiral himself. The wreck of the fallen mast was cleared, and the foresail set to maintain speed, but, despite all, the Intrepid dropped astern in the line. Cornwall in the Revenge was taking his place at the moment, and fearing that the Intrepid would come back upon him, if in her wake, he brought up first a little to windward, on her quarter; then, thinking that she was holding her way, he bore up again. At this particular instant he looked behind, and saw the admiral and other ships a considerable distance astern and to windward; much Lestock's position in Mathews's action. This was the stoppage already mentioned, to wait for the two other ships. Had Cornwall been Burrish, he might in this have seen occasion for waiting himself; but he saw rather the need of the crippled ship. The Revenge took position on the Intrepid's lee quarter, to support her against the enemy's fire, concentrated on her when her mast was seen to fall. As her way slackened, the Revenge approached her, and about fifteen minutes later the ship following, the Princess Louisa,—one of those for which Byng had waited,—loomed up close behind Cornwall, who expected her to run him on board, her braces being shot away. She managed, however, with the helm to back her sails, and dropped clear; but in so doing got in the way of the vessel next after her, the Trident, which immediately preceded Byng. The captain of the Trident, slanting down with the rest of the division, saw the situation, put his helm up, ran under the stern of the Louisa, passed on her lee side,—nearest the enemy,—and ranged up behind the Revenge; but in doing this he not only crossed the stern of the Louisa, but the bow of the admiral's ship—the Ramillies.

Under proper management the Ramillies doubtless could have done just what the Trident did,—keep away with the helm, till the ships ahead of her were cleared; she would be at least hasting towards the enemy. But the noise of battle was in the air, and the crew of the Ramillies began to fire without orders, at an improper distance. The admiral permitted them to continue, and the smoke enveloping the ship prevented fully noting the incidents just narrated. It was, however, seen before the firing that the Louisa was come up into the wind with her topsails shaking, and the Trident passing her to leeward. There should, therefore, have been some preparation of mind for the fact suddenly reported to the admiral, by a military passenger on the quarter deck, that a British ship was close aboard, on the lee bow. It was the Trident that had crossed from windward to leeward for the reasons given, and an instant later the Louisa was seen on the weather bow. Instead of keeping off, as the Trident had done, the admiral ordered the foresail hauled up, the helm down, luffed the ship to the wind, and braced the fore-topsail sharp aback; the effect of which was first to stop her way, and then to pay her head off to leeward, clear of the two vessels. About quarter of an hour elapsed, by Captain Gardiner's evidence, from the time that the Ramillies's head pointed clear of the Trident and Louisa before sail was again made to go forward to aid the van. The battle was already lost, and in fact had passed out of Byng's control, owing to his previous action; nevertheless this further delay, though probably due only to the importance attached by the admiral to regularity of movement, had a discreditable appearance.