полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

The following year the same strategic and political mistake was made. It is the nature of an enterprise such as James's, dependent upon a weaker people and foreign help, to lose strength if it does not progress; but the chances were still in his favor, provided France co-operated heartily, and above all, with her fleet. It is equally the nature of a merely military navy like that of France to be strongest at the beginning of hostilities; whereas that of the allied sea powers grew daily stronger, drawing upon the vast resources of their merchant shipping and their wealth. The disparity of force was still in favor of France in 1690, but it was not as great as the year before. The all-important question was where to direct it. There were two principal courses, involving two views of naval strategy. The one was to act against the allied fleet, whose defeat, if sufficiently severe, might involve the fall of William's throne in England; the other was to make the fleet subsidiary to the Irish campaign. The French king decided upon the former, which was undoubtedly the proper course; but there was no reason for neglecting, as he did, the important duty of cutting off the communications between the two islands. As early as March he had sent a large fleet with six thousand troops and supplies of war, which were landed without any trouble in the southern ports of Ireland; but after performing that service, the ships employed returned to Brest, and there remained inactive during May and June while the grand fleet under the Comte de Tourville was assembling. During those two months the English were gathering an army on their west coast, and on the 21st of June, William embarked his forces at Chester on board two hundred and eighty-eight transports, escorted by only six men-of-war. On the 24th he landed in Carrickfergus, and the ships-of-war were dismissed to join the English grand fleet, which, however, they were not able to do; Tourville's ships having in the mean time got to sea and occupied the channel to the eastward. There is nothing more striking than the carelessness shown by both the contending parties, during the time that Ireland was in dispute, as to the communications of their opponents with the island; but this was especially strange in the French, as they had the larger forces, and must have received pretty accurate information of what was going on from disaffected persons in England. It appears that a squadron of twenty-five frigates, to be supported by ships-of-the-line, were told off for duty in St. George's Channel; but they never reached their station, and only ten of the frigates had got as far as Kinsale by the time James had lost all at the battle of the Boyne. The English communications were not even threatened for an hour.

Tourville's fleet, complete in numbers, having seventy-eight ships, of which seventy were in the line-of-battle, with twenty-two fire-ships, got to sea June 22, the day after William embarked. On the 30th the French were off the Lizard, to the dismay of the English admiral, who was lying off the Isle of Wight in such an unprepared attitude that he had not even lookout ships to the westward. He got under way, standing off-shore to the southeast, and was joined from time to time, during the next ten days, by other English and Dutch ships. The two fleets continued moving to the eastward, sighting each other from time to time.

The political situation in England was critical. The Jacobites were growing more and more open in their demonstrations, Ireland had been in successful revolt for over a year, and William was now there, leaving only the queen in London. The urgency of the case was such that the council decided the French fleet must be fought, and orders to that effect were sent to the English admiral, Herbert. In obedience to his instructions he went out, and on the 10th of July, being to windward, with the wind at northeast, formed his line-of-battle, and then stood down to attack the French, who waited for him, with their foretopsails aback69 on the starboard tack, heading to the northward and westward.

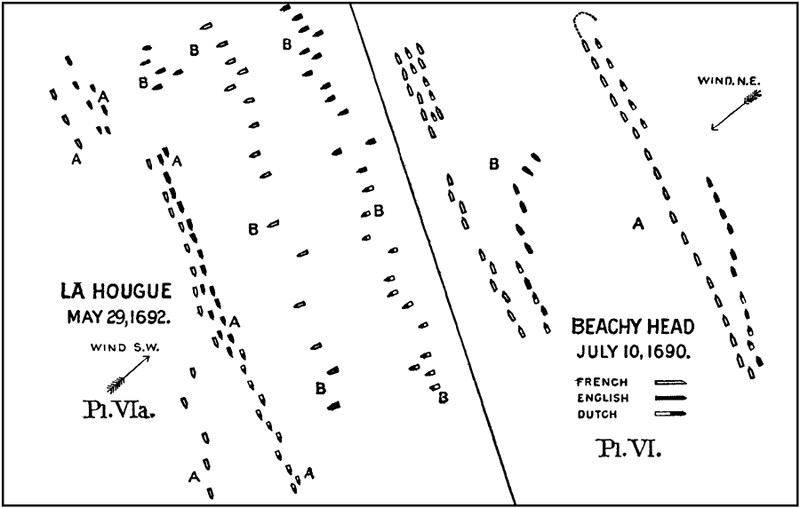

The fight that followed is known as the battle of Beachy Head. The ships engaged were, French seventy, English and Dutch according to their own account fifty-six, according to the French sixty. In the allied line of battle the Dutch were in the van; the English, commanded in person by Herbert, in the centre; and the rear was made up partly of English and partly of Dutch ships. The stages of the battle were as follows:—

1. The allies, being to windward, bore down together in line abreast. As usual, this manœuvre was ill performed, and as also generally happens, the van came under fire before the centre and rear, and bore the brunt of the injury.

2. Admiral Herbert, though commander-in-chief, failed to attack vigorously with the centre, keeping it at long range. The allied van and rear came to close action (Plate VI., A). Paul Hoste's70 account of this manœuvre of the allies is that the admiral intended to fall mainly on the French rear. To that end he closed the centre to the rear and kept it to windward at long cannon-shot (refused it), so as to prevent the French from tacking and doubling on the rear. If that were his purpose, his plan, though tolerably conceived in the main, was faulty in detail, for this manœuvre of the centre left a great gap between it and the van. He should rather have attacked, as Ruyter did at the Texel, as many of the rear ships as he thought he could deal with, and refused his van, assigning to it the part of checking the French van. It may be conceded that an admiral who, from inferior numbers, cannot spread as long and close a line as his enemy, should not let the latter overlap the extremities of his fleet; but he should attain his end not, as Herbert did, by leaving a great opening in the centre, but by increasing each interval between the ships refused. The allied fleet was thus exposed to be doubled on at two points, both van and centre; and both points were attacked.

3. The commander of the French van, seeing the Dutch close to his line and more disabled than himself, pressed six of his leading ships ahead, where they went about, and so put the Dutch between two fires (Plate VI. B).

Pl. VI. and Pl. VIa.

At the same time Tourville, finding himself without adversaries in the centre, having beaten off the leading division of the enemy's centre, pushed forward his own leading ships, which Herbert's dispositions had left without opponents; and these fresh ships strengthened the attack upon the Dutch in the van (B).

This brought about a mêlée at the head of the lines, in which the Dutch, being inferior, suffered heavily. Luckily for the allies the wind fell calm; and while Tourville himself and other French ships got out their boats to tow into action again, the allies were shrewd enough to drop anchor with all sail set, and before Tourville took in the situation the ebb-tide, setting southwest, had carried his fleet out of action. He finally anchored a league from his enemy.

At nine P.M., when the tide changed, the allies weighed and stood to the eastward. So badly had many of them been mauled, that, by English accounts, it was decided rather to destroy the disabled ships than to risk a general engagement to preserve them.

Tourville pursued; but instead of ordering a general chase, he kept the line-of-battle, reducing the speed of the fleet to that of the slower ships. The occasion was precisely one of those in which a mêlée is permissible, indeed, obligatory. An enemy beaten and in flight should be pursued with ardor, and with only so much regard to order as will prevent the chasing vessels from losing mutual support,—a condition which by no means implies such relative bearings and distances as are required in the beginning or middle of a well-contested action. The failure to order such general pursuit indicates the side on which Tourville's military character lacked completeness; and the failure showed itself, as is apt to be the case, at the supreme moment of his career. He never had such another opportunity as in this, the first great general action in which he commanded in chief, and which Hoste, who was on board the flag-ship, calls the most complete naval victory ever gained. It was so indeed at that time,—the most complete, but not the most decisive, as it perhaps might have been. The French, according to Hoste, lost not even a boat, much less a ship, which, if true, makes yet more culpable the sluggishness of the pursuit; while the allies fled, casting sixteen of their ships ashore and burning them in sight of the enemy, who pursued as far as the Downs. The English indeed give the allied loss as only eight ships,—an estimate probably full as much out one way as the French the other. Herbert took his fleet to the Thames, and baffled the enemy's further pursuit by removing the buoys.71

Tourville's is the only great historical name among the seamen of this war, if we except the renowned privateersmen at whose head was Jean Bart. Among the English, extraordinary merit cannot be claimed for any one of the gallant and enterprising men who commanded squadrons. Tourville, who by this time had served afloat for nearly thirty years, was at once a seaman and a military man. With superb courage, of which he had given dazzling examples in his youth, he had seen service wherever the French fleets had fought,—in the Anglo-Dutch war, in the Mediterranean, and against the Barbary pirates. Reaching the rank of admiral, he commanded in person all the largest fleets sent out during the earlier years of this war, and he brought to the command a scientific knowledge of tactics, based upon both theory and experience, joined to that practical acquaintance with the seaman's business which is necessary in order to apply tactical principles upon the ocean to the best advantage. But with all these high qualities he seems to have failed, where so many warriors fail, in the ability to assume a great responsibility.72 The caution in his pursuit of the allies after Beachy Head, though so different in appearance, came from the same trait which impelled him two years later to lead his fleet into almost certain destruction at La Hougue, because he had the king's order in his pocket. He was brave enough to do anything, but not strong enough to bear the heaviest burdens. Tourville was in fact the forerunner of the careful and skilful tacticians of the coming era, but with the savor still of the impetuous hard-fighting which characterized the sea commanders of the seventeenth century. He doubtless felt, after Beachy Head, that he had done very well and could be satisfied; but he could not have acted as he did had he felt, to use Nelson's words, that "if we had taken ten ships out of the enemy's eleven, and let the eleventh escape, being able to take her, I could never call such a good day."

The day after the sea fight off Beachy Head, with its great but still partial results, the cause of James II. was lost ashore in Ireland. The army which William had been allowed to transport there unmolested was superior in number and quality to that of James, as William himself was superior as a leader to the ex-king. The counsel of Louis XIV. was that James should avoid decisive action, retiring if necessary to the Shannon, in the midst of a country wholly devoted to him. It was, however, a good deal to ask, this abandonment of the capital after more than a year's occupancy, with all the consequent moral effect; it would have been much more to the purpose to stop William's landing. James undertook to cover Dublin, taking up the line of the river Boyne, and there on the 11th of July the two armies met, with the result that James was wholly defeated. The king himself fled to Kinsale, where he found ten of those frigates that had been meant to control St. George's Channel. He embarked, and again took refuge in France, begging Louis to improve the victory at Beachy Head by landing him with another French army in England itself. Louis angrily refused, and directed that the troops still remaining in Ireland should be at once withdrawn.

The chances of a rising in favor of James, at least upon the shores of the Channel, if they existed at all, were greatly exaggerated by his own imagination. After the safe retreat of the allied fleet to the Thames, Tourville, in accordance with his instructions, made several demonstrations in the south of England; but they were wholly fruitless in drawing out any show of attachment to the Stuart cause.

In Ireland it was different. The Irish army with its French contingent fell back, after the battle of the Boyne, to the Shannon, and there again made a stand; while Louis, receding from his first angry impulse, continued to send reinforcements and supplies. But the increasing urgency of the continental war kept him from affording enough support, and the war in Ireland came to a close a little over a year later, by the defeat at Aghrim and capitulation of Limerick. The battle of the Boyne, which from its peculiar religious coloring has obtained a somewhat factitious celebrity, may be taken as the date at which the English crown was firmly fixed on William's head. Yet it would be more accurate to say that the success of William, and with it the success of Europe against Louis XIV. in the War of the League of Augsburg, was due to the mistakes and failure of the French naval campaign in 1690; though in that campaign was won the most conspicuous single success the French have ever gained at sea over the English. As regards the more striking military operations, it is curious to remark that Tourville sailed the day after William left Chester, and won Beachy Head the day before the battle of the Boyne; but the real failure lay in permitting William to transport that solid body of men without hindrance. It might have been favorable to French policy to let him get into Ireland, but not with such a force at his back. The result of the Irish campaign was to settle William safely on the English throne and establish the Anglo-Dutch alliance; and the union of the two sea peoples under one crown was the pledge, through their commercial and maritime ability, and the wealth they drew from the sea, of the successful prosecution of the war by their allies on the continent.

The year 1691 was distinguished by only one great maritime event. This was ever afterward known in France as Tourville's "deep-sea" or "off-shore" cruise; and the memory of it as a brilliant strategic and tactical display remains to this day in the French navy. That staying power, which has already been spoken of as distinctive of nations whose sea power is not a mere military institution, but based upon the character and pursuits of the people, had now come into play with the allies. Notwithstanding the defeat and loss of Beachy Head, the united fleets took the sea in 1691 with one hundred ships-of-the-line under the command of Admiral Russell. Tourville could only gather seventy-two, the same number as the year before. "With these he left Brest June 25. As the enemy had not yet appeared upon the coasts of the Channel, he took up his cruising ground at the entrance, sending lookout ships in all directions. Informed that the allies had stationed themselves near the Scilly Islands to cover the passage of a convoy expected from the Levant, Tourville did not hesitate to steer for the English coasts, where the approaching arrival of another merchant fleet from Jamaica was equally expected. Deceiving the English cruisers by false courses, he reached the latter fleet, took from it several ships, and dispersed it before Russell could come up to fight him. When at last Tourville was in presence of the allied fleet, he manœuvred so skilfully, always keeping the weather-gage, that the enemy, drawn far out into the ocean, lost fifty days without finding an opportunity to engage. During this time French privateers, scattered throughout the Channel, harassed the enemy's commerce and protected convoys sent into Ireland. Worn out by fruitless efforts, Russell steered for the Irish coast. Tourville, after having protected the return of the French convoys, anchored again in Brest Roads."

The actual captures made by Tourville's own fleet were insignificant, but its service to the commerce-destroying warfare of the French, by occupying the allies, is obvious; nevertheless, the loss of English commerce was not as great this year as the next. The chief losses of the allies seem to have been in the Dutch North Sea trade.

The two wars, continental and maritime, that were being waged, though simultaneous, were as yet independent of each other. It is unnecessary in connection with our subject to mention the operations of the former. In 1692 there occurred the great disaster to the French fleet which is known as the battle of La Hougue. In itself, considered tactically, it possesses little importance, and the actual results have been much exaggerated; but popular report has made it one of the famous sea battles of the world, and therefore it cannot be wholly passed by.

Misled by reports from England, and still more by the representations of James, who fondly nursed his belief that the attachment of many English naval officers to his person was greater than their love of country or faithfulness to their trust, Louis XIV. determined to attempt an invasion of the south coast of England, led by James in person. As a first step thereto, Tourville, at the head of between fifty and sixty ships-of-the-line, thirteen of which were to come from Toulon, was to engage the English fleet; from which so many desertions were expected as would, with the consequent demoralization, yield the French an easy and total victory. The first hitch was in the failure of the Toulon fleet, delayed by contrary winds, to join; and Tourville went to sea with only forty-four ships, but with a peremptory order from the king to fight when he fell in with the enemy, were they few or many, and come what might.

On the 29th of May, Tourville saw the allies to the northward and eastward; they numbered ninety-nine sail-of-the-line. The wind being southwest, he had the choice of engaging, but first summoned all the flag-officers on board his own ship, and put the question to them whether he ought to fight. They all said not, and he then handed them the order of the king.73 No one dared dispute that; though, had they known it, light vessels with contrary orders were even then searching for the fleet. The other officers then returned to their ships, and the whole fleet kept away together for the allies, who waited for them, on the starboard tack, heading south-southeast, the Dutch occupying the van, the English the centre and rear. When they were within easy range, the French hauled their wind on the same tack, keeping the weather-gage. Tourville, being so inferior in numbers, could not wholly avoid the enemy's line extending to the rear of his own, which was also necessarily weak from its extreme length; but he avoided Herbert's error at Beachy Head, keeping his van refused with long intervals between the ships, to check the enemy's van, and engaging closely with his centre and rear (Plate VIa. A, A, A). It is not necessary to follow the phases of this unequal fight; the extraordinary result was that when the firing ceased at night, in consequence of a thick fog and calm, not a single French ship had struck her colors nor been sunk. No higher proof of military spirit and efficiency could be given by any navy, and Tourville's seamanship and tactical ability contributed largely to the result, which it must also be confessed was not creditable to the allies. The two fleets anchored at nightfall (B, B, B), a body of English ships (B’) remaining to the southward and westward of the French, Later on, these cut their cables and allowed themselves to drift through the French line in order to rejoin their main body; in doing which they were roughly handled.

Having amply vindicated the honor of his fleet, and shown the uselessness of further fighting, Tourville now thought of retreat, which was begun at midnight with a light northeast wind and continued all the next day. The allies pursued, the movements of the French being much embarrassed by the crippled condition of the flag-ship "Royal Sun," the finest ship in the French navy, which the admiral could not make up his mind to destroy. The direction of the main retreat was toward the Channel Islands, thirty-five ships being with the admiral; of them twenty passed with the tidal current through the dangerous passage known as the Race of Alderney, between the island of that name and the mainland, and got safe to St. Malo. Before the remaining fifteen could follow, the tide changed; and the anchors which had been dropped dragging, these ships were carried to the eastward and to leeward of the enemy. Three sought refuge in Cherbourg, which had then neither breakwater nor port, the remaining twelve at Cape La Hougue; and they were all burned either by their own crews or by the allies. The French thus lost fifteen of the finest ships in their navy, the least of which carried sixty guns; but this was little more than the loss of the allies at Beachy Head. The impression made upon the public mind, accustomed to the glories and successes of Louis XIV., was out of all proportion to the results, and blotted out the memory of the splendid self-devotion of Tourville and his followers. La Hougue was also the last general action fought by the French fleet, which did rapidly dwindle away in the following years, so that this disaster seemed to be its death-blow. As a matter of fact, however, Tourville went to sea the next year with seventy ships, and the losses were at the time repaired. The decay of the French navy was not due to any one defeat, but to the exhaustion of France and the great cost of the continental war; and this war was mainly sustained by the two sea peoples whose union was secured by the success of William in the Irish campaign. Without asserting that the result would have been different had the naval operations of France been otherwise directed in 1690, it may safely be said that their misdirection was the immediate cause of things turning out as they did, and the first cause of the decay of the French navy.

The five remaining years of the War of the League of Augsburg, in which all Europe was in arms against France, are marked by no great sea battles, nor any single maritime event of the first importance. To appreciate the effect of the sea power of the allies, it is necessary to sum up and condense an account of the quiet, steady pressure which it brought to bear and maintained in all quarters against France. It is thus indeed that sea power usually acts, and just because so quiet in its working, it is the more likely to be unnoticed and must be somewhat carefully pointed out.

The head of the opposition to Louis XIV. was William III., and his tastes being military rather than naval combined with the direction of Louis' policy to make the active war continental rather than maritime; while the gradual withdrawal of the great French fleets, by leaving the allied navies without enemies on the sea, worked in the same way. Furthermore, the efficiency of the English navy, which was double in numbers that of the Dutch, was at this time at a low pitch; the demoralizing effects of the reign of Charles II. could not be wholly overcome during the three years of his brother's rule, and there was a yet more serious cause of trouble growing out of the political state of England. It has been said that James believed the naval officers and seamen to be attached to his person; and, whether justly or unjustly, this thought was also in the minds of the present rulers, causing doubts of the loyalty and trustworthiness of many officers, and tending to bring confusion into the naval administration. We are told that "the complaints made by the merchants were extremely well supported, and showed the folly of preferring unqualified men to that board which directed the naval power of England; and yet the mischief could not be amended, because the more experienced people who had been long in the service were thought disaffected, and it appeared the remedy might have proved worse than the disease."74 Suspicion reigned in the cabinet and the city, factions and irresolution among the officers; and a man who was unfortunate or incapable in action knew that the yet more serious charge of treason might follow his misadventure.

After La Hougue, the direct military action of the allied navies was exerted in three principal ways, the first being in attacks upon the French ports, especially those in the Channel and near Brest. These had rarely in view more than local injury and the destruction of shipping, particularly in the ports whence the French privateers issued; and although on some occasions the number of troops embarked was large, William proposed to himself little more than the diversion which such threats caused, by forcing Louis to take troops from the field for coast defence. It may be said generally of all these enterprises against the French coast, in this and later wars, that they effected little, and even as a diversion did not weaken the French armies to any great extent. If the French ports had been less well defended, or French water-ways open into the heart of the country, like our own Chesapeake and Delaware bays and the Southern sounds, the result might have been different.