полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

Pl. I.

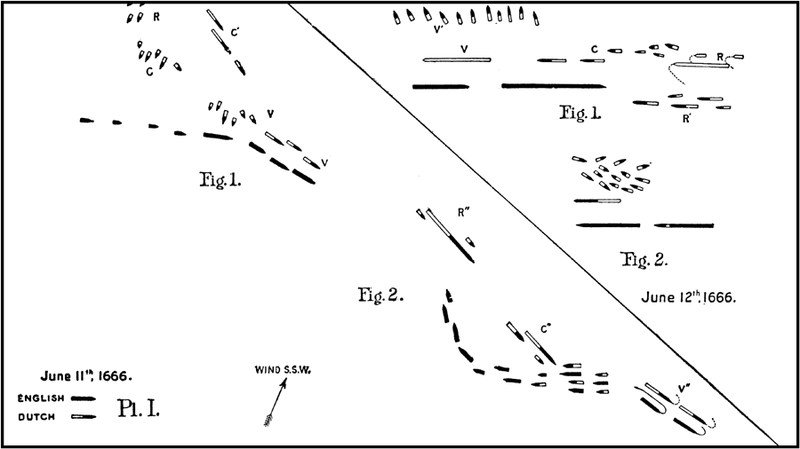

The Dutch had sailed for the English coast with a fair easterly wind, but it changed later to southwest with thick weather, and freshened, so that De Ruyter, to avoid being driven too far, came to anchor between Dunkirk and the Downs.27 The fleet then rode with its head to the south-southwest and the van on the right; while Tromp, who commanded the rear division in the natural order, was on the left. For some cause this left was most to windward, the centre squadron under Ruyter being to leeward, and the right, or van, to leeward again of the centre.28 This was the position of the Dutch fleet at daylight of June 11, 1666; and although not expressly so stated, it is likely, from the whole tenor of the narratives, that it was not in good order.

The same morning Monk, who was also at anchor, made out the Dutch fleet to leeward, and although so inferior in numbers determined to attack at once, hoping that by keeping the advantage of the wind he would be able to commit himself only so far as might seem best. He therefore stood along the Dutch line on the starboard tack, leaving the right and centre out of cannon-shot, until he came abreast of the left, Tromp's squadron. Monk then had thirty-five ships well in hand; but the rear had opened and was straggling, as is apt to be the case with long columns. With the thirty-five he then put his helm up and ran down for Tromp, whose squadron cut their cables and made sail on the same tack (V’); the two engaged lines thus standing over toward the French coast, and the breeze heeling the ships so that the English could not use their lower-deck guns (Fig. 2, V’’). The Dutch centre and rear also cut (Fig. 1, C’), and followed the movement, but being so far to leeward, could not for some time come into action. It was during this time that a large Dutch ship, becoming separated from her own fleet, was set on fire and burned, doubtless the ship in which was Count de Guiche.

As they drew near Dunkirk the English went about, probably all together; for in the return to the northward and westward the proper English van fell in with and was roughly handled by the Dutch centre under Ruyter himself (Fig. 2, C’’). This fate would be more likely to befall the rear, and indicates that a simultaneous movement had reversed the order. The engaged ships had naturally lost to leeward, thus enabling Ruyter to fetch up with them. Two English flag-ships were here disabled and cut off; one, the "Swiftsure," hauled down her colors after the admiral, a young man of only twenty-seven, was killed. "Highly to be admired," says a contemporary writer, "was the resolution of Vice-Admiral Berkeley, who, though cut off from the line, surrounded by enemies, great numbers of his men killed, his ship disabled and boarded on all sides, yet continued fighting almost alone, killed several with his own hand, and would accept no quarter; till at length, being shot in the throat with a musket-ball, he retired into the captain's cabin, where he was found dead, extended at his full length upon a table, and almost covered with his own blood." Quite as heroic, but more fortunate in its issue, was the conduct of the other English admiral thus cut off; and the incidents of his struggle, though not specially instructive otherwise, are worth quoting, as giving a lively picture of the scenes which passed in the heat of the contests of those days, and afford coloring to otherwise dry details.

"Being in a short time completely disabled, one of the enemy's fire-ships grappled him on the starboard quarter; he was, however, freed by the almost incredible exertions of his lieutenant, who, having in the midst of the flames loosed the grappling-irons, swung back on board his own ship unhurt. The Dutch, bent on the destruction of this unfortunate ship, sent a second which grappled her on the larboard side, and with greater success than the former; for the sails instantly taking fire, the crew were so terrified that nearly fifty of them jumped overboard. The admiral, Sir John Harman, seeing this confusion, ran with his sword drawn among those who remained, and threatened with instant death the first man who should attempt to quit the ship, or should not exert himself to quench the flames. The crew then returned to their duty and got the fire under; but the rigging being a good deal burned, one of the topsail yards fell and broke Sir John's leg. In the midst of this accumulated distress, a third fire-ship prepared to grapple him, but was sunk by the guns before she could effect her purpose. The Dutch vice-admiral, Evertzen, now bore down to him and offered quarter; but Sir John replied, 'No, no, it is not come to that yet,' and giving him a broadside, killed the Dutch commander; after which the other enemies sheered off."29

It is therefore not surprising that the account we have been following reported two English flag-ships lost, one by a fire-ship. "The English chief still continued on the port tack, and," says the writer, "as night fell we could see him proudly leading his line past the squadron of North Holland and Zealand [the actual rear, but proper van], which from noon up to that time had not been able to reach the enemy [Fig. 2, R’’] from their leewardly position." The merit of Monk's attack as a piece of grand tactics is evident, and bears a strong resemblance to that of Nelson at the Nile. Discerning quickly the weakness of the Dutch order, he had attacked a vastly superior force in such a way that only part of it could come into action; and though the English actually lost more heavily, they carried off a brilliant prestige and must have left considerable depression and heart-burning among the Dutch. The eye-witness goes on: "The affair continued until ten P.M., friends and foes mixed together and as likely to receive injury from one as from the other. It will be remarked that the success of the day and the misfortunes of the English came from their being too much scattered, too extended in their line; but for which we could never have cut off a corner of them, as we did. The mistake of Monk was in not keeping his ships better together;" that is, closed up. The remark is just, the criticism scarcely so; the opening out of the line was almost unavoidable in so long a column of sailing-ships, and was one of the chances taken by Monk when he offered battle.

The English stood off on the port tack to the west or west-northwest, and next day returned to the fight. The Dutch were now on the port tack in natural order, the right leading, and were to windward; but the enemy, being more weatherly and better disciplined, soon gained the advantage of the wind. The English this day had forty-four ships in action, the Dutch about eighty; many of the English, as before said, larger. The two fleets passed on opposite tacks, the English to windward;30 but Tromp, in the rear, seeing that the Dutch order of battle was badly formed, the ships in two or three lines, overlapping and so masking each other's fire, went about and gained to windward of the enemy's van (R’); which he was able to do from the length of the line, and because the English, running parallel to the Dutch order, were off the wind. "At this moment two flag-officers of the Dutch van kept broad off, presenting their sterns to the English (V’). Ruyter, greatly astonished, tried to stop them, but in vain, and therefore felt obliged to imitate the manœuvre in order to keep his squadron together; but he did so with some order, keeping some ships around him, and was joined by one of the van ships, disgusted with the conduct of his immediate superior. Tromp was now in great danger, separated [by his own act first and then by the conduct of the van] from his own fleet by the English, and would have been destroyed but for Ruyter, who, seeing the urgency of the case, hauled up for him," the van and centre thus standing back for the rear on the opposite tack to that on which they entered action. This prevented the English from keeping up the attack on Tromp, lest Ruyter should gain the wind of them, which they could not afford to yield because of their very inferior numbers. Both the action of Tromp and that of the junior flag-officers in the van, though showing very different degrees of warlike ardor, bring out strongly the lack of subordination and of military feeling which has been charged against the Dutch officers as a body; no signs of which appear among the English at this time.

How keenly Ruyter felt the conduct of his lieutenants was manifested when "Tromp, immediately after this partial action, went on board his flagship. The seamen cheered him; but Ruyter said, 'This is no time for rejoicing, but rather for tears.' Indeed, our position was bad, each squadron acting differently, in no line, and all the ships huddled together like a flock of sheep, so packed that the English might have surrounded all of them with their forty ships [June 12, Fig. 2]. The English were in admirable order, but did not push their advantage as they should, whatever the reason." The reason no doubt was the same that often prevented sailing-ships from pressing an advantage,—disability from crippled spars and rigging, added to the inexpediency of such inferior numbers risking a decisive action.

Ruyter was thus able to draw his fleet out into line again, although much maltreated by the English, and the two fleets passed again on opposite tacks, the Dutch to leeward, and Ruyter's ship the last in his column. As he passed the English rear, he lost his maintopmast and mainyard. After another partial rencounter the English drew away to the northwest toward their own shores, the Dutch following them; the wind being still from southwest, but light. The English were now fairly in retreat, and the pursuit continued all night, Ruyter's own ship dropping out of sight in the rear from her crippled state.

The third day Monk continued retreating to the westward. He burned, by the English accounts, three disabled ships, sent ahead those that were most crippled, and himself brought up the rear with those that were in fighting condition, which are variously stated, again by the English, at twenty-eight and sixteen in number (Plate II., June 13). One of the largest and finest of the English fleet, the "Royal Prince," of ninety guns, ran aground on the Galloper Shoal and was taken by Tromp (Plate II. a); but Monk's retreat was so steady and orderly that he was otherwise unmolested. This shows that the Dutch had suffered very severely. Toward evening Rupert's squadron was seen; and all the ships of the English fleet, except those crippled in action, were at last united.

The next day the wind came out again very fresh from the southwest, giving the Dutch the weather-gage. The English, instead of attempting to pass upon opposite tacks, came up from astern relying upon the speed and handiness of their ships. So doing, the battle engaged all along the line on the port tack, the English to leeward.31 The Dutch fire-ships were badly handled and did no harm, whereas the English burned two of their enemies. The two fleets ran on thus, exchanging broadsides for two hours, at the end of which time the bulk of the English fleet had passed through the Dutch line.32 All regularity of order was henceforward lost. "At this moment," says the eye-witness, "the lookout was extraordinary, for all were separated, the English as well as we. But luck would have it that the largest of our fractions surrounding the admiral remained to windward, and the largest fraction of the English, also with their admiral, remained to leeward [Figs. 1 and 2, C and C’]. This was the cause of our victory and their ruin. Our admiral had with him thirty-five or forty ships of his own and of other squadrons, for the squadrons were scattered and order much lost. The rest of the Dutch ships had left him. The leader of the van, Van Ness, had gone off with fourteen ships in chase of three or four English ships, which under a press of sail had gained to windward of the Dutch van [Fig. 1, V]. Van Tromp with the rear squadron had fallen to leeward, and so had to keep on [to leeward of Ruyter and the English main body, Fig. 1, R] after Van Ness, in order to rejoin the admiral by passing round the English centre." De Ruyter and the English main body kept up a sharp action, beating to windward all the time. Tromp, having carried sail, overtook Van Ness, and returned bringing the van back with him (V’, R’); but owing to the constant plying to windward of the English main body he came up to leeward of it and could not rejoin Ruyter, who was to windward (Fig. 3, V’’, R’’). Ruyter, seeing this, made signal to the ships around him, and the main body of the Dutch kept away before the wind (Fig 3, C’’), which was then very strong. "Thus in less than no time we found ourselves in the midst of the English; who, being attacked on both sides, were thrown into confusion and saw their whole order destroyed, as well by dint of the action, as by the strong wind that was then blowing. This was the hottest of the fight [Fig. 3]. We saw the high admiral of England separated from his fleet, followed only by one fire-ship. With that he gained to windward, and passing through the North Holland squadron, placed himself again at the head of fifteen or twenty ships that rallied to him."

Pl. II.

Thus ended this great sea-fight, the most remarkable, in some of its aspects, that has ever been fought upon the ocean. Amid conflicting reports it is not possible to do more than estimate the results. A fairly impartial account says: "The States lost in these actions three vice-admirals, two thousand men, and four ships. The loss of the English was five thousand killed and three thousand prisoners; and they lost besides seventeen ships, of which nine remained in the hands of the victors."33 There is no doubt that the English had much the worst of it, and that this was owing wholly to the original blunder of weakening the fleet by a great detachment sent in another direction. Great detachments are sometimes necessary evils, but in this case no necessity existed. Granting the approach of the French, the proper course for the English was to fall with their whole fleet upon the Dutch before their allies could come up. This lesson is as applicable to-day as it ever was. A second lesson, likewise of present application, is the necessity of sound military institutions for implanting correct military feeling, pride, and discipline. Great as was the first blunder of the English, and serious as was the disaster, there can be no doubt that the consequences would have been much worse but for the high spirit and skill with which the plans of Monk were carried out by his subordinates, and the lack of similar support to Ruyter on the part of the Dutch subalterns. In the movements of the English, we hear nothing of two juniors turning tail at a critical moment, nor of a third, with misdirected ardor, getting on the wrong side of the enemy's fleet. Their drill also, their tactical precision, was remarked even then. The Frenchman De Guiche, after witnessing this Four Days' Fight, wrote:—

"Nothing equals the beautiful order of the English at sea. Never was a line drawn straighter than that formed by their ships; thus they bring all their fire to bear upon those who draw near them.... They fight like a line of cavalry which is handled according to rule, and applies itself solely to force back those who oppose; whereas the Dutch advance like cavalry whose squadrons leave their ranks and come separately to the charge."34

The Dutch government, averse to expense, unmilitary in its tone, and incautious from long and easy victory over the degenerate navy of Spain, had allowed its fleet to sink into a mere assembly of armed merchantmen. Things were at their worst in the days of Cromwell. Taught by the severe lessons of that war, the United Provinces, under an able ruler, had done much to mend matters, but full efficiency had not yet been gained.

"In 1666 as in 1653," says a French naval writer, "the fortune of war seemed to lean to the side of the English. Of the three great battles fought two were decided victories; and the third, though adverse, had but increased the glory of her seamen. This was due to the intelligent boldness of Monk and Rupert, the talents of part of the admirals and captains, and the skill of the seamen and soldiers under them. The wise and vigorous efforts made by the government of the United Provinces, and the undeniable superiority of Ruyter in experience and genius over any one of his opponents, could not compensate for the weakness or incapacity of part of the Dutch officers, and the manifest inferiority of the men under their orders."35

England, as has been said before, still felt the impress of Cromwell's iron hand upon her military institutions; but that impress was growing weaker. Before the next Dutch war Monk was dead, and was poorly replaced by the cavalier Rupert. Court extravagance cut down the equipment of the navy as did the burgomaster's parsimony, and court corruption undermined discipline as surely as commercial indifference. The effect was evident when the fleets of the two countries met again, six years later.

There was one well-known feature of all the military navies of that day which calls for a passing comment; for its correct bearing and value is not always, perhaps not generally, seen. The command of fleets and of single vessels was often given to soldiers, to military men unaccustomed to the sea, and ignorant how to handle the ship, that duty being intrusted to another class of officer. Looking closely into the facts, it is seen that this made a clean division between the direction of the fighting and of the motive power of the ship. This is the essence of the matter; and the principle is the same whatever the motive power may be. The inconvenience and inefficiency of such a system was obvious then as it is now, and the logic of facts gradually threw the two functions into the hands of one corps of officers, the result being the modern naval officer, as that term is generally understood.36 Unfortunately, in this process of blending, the less important function was allowed to get the upper hand; the naval officer came to feel more proud of his dexterity in managing the motive power of his ship than of his skill in developing her military efficiency. The bad effects of this lack of interest in military science became most evident when the point of handling fleets was reached, because for that military skill told most, and previous study was most necessary; but it was felt in the single ship as well. Hence it came to pass, and especially in the English navy, that the pride of the seaman took the place of the pride of the military man. The English naval officer thought more of that which likened him to the merchant captain than of that which made him akin to the soldier. In the French navy this result was less general, owing probably to the more military spirit of the government, and especially of the nobility, to whom the rank of officer was reserved. It was not possible that men whose whole association was military, all of whose friends looked upon arms as the one career for a gentleman, could think more of the sails and rigging than of the guns or the fleet. The English corps of officers was of different origin. There was more than the writer thought in Macaulay's well-known saying: "There were seamen and there were gentlemen in the navy of Charles II.; but the seamen were not gentlemen, and the gentlemen were not seamen." The trouble was not in the absence or presence of gentlemen as such, but in the fact that under the conditions of that day the gentleman was pre-eminently the military element of society; and that the seaman, after the Dutch wars, gradually edged the gentleman, and with him the military tone and spirit as distinguished from simple courage, out of the service. Even "such men of family as Herbert and Russell, William III.'s admirals," says the biographer of Lord Hawke, "were sailors indeed, but only able to hold their own by adopting the boisterous manners of the hardy tarpaulin." The same national traits which made the French inferior as seamen made them superior as military men; not in courage, but in skill. To this day the same tendency obtains; the direction of the motive power has no such consideration as the military functions in the navies of the Latin nations. The studious and systematic side of the French character also inclined the French officer, when not a trifler, to consider and develop tactical questions in a logical manner; to prepare himself to handle fleets, not merely as a seaman but as a military man. The result showed, in the American Revolutionary War, that despite a mournful history of governmental neglect, men who were first of all military men, inferior though they were in opportunities as seamen to their enemies, could meet them on more than equal terms as to tactical skill, and were practically their superiors in handling fleets. The false theory has already been pointed out, which directed the action of the French fleet not to crushing its enemy, but to some ulterior aim; but this does not affect the fact that in tactical skill the military men were superior to the mere seamen, though their tactical skill was applied to mistaken strategic ends. The source whence the Dutch mainly drew their officers does not certainly appear; for while the English naval historian in 1666 says that most of the captains of their fleet were sons of rich burgomasters, placed there for political reasons by the Grand Pensionary, and without experience, Duquesne, the ablest French admiral of the day, comments in 1676 on the precision and skill of the Dutch captains in terms very disparaging to his own. It is likely, from many indications, that they were generally merchant seamen, with little original military feeling; but the severity with which the delinquents were punished both by the State and by popular frenzy, seems to have driven these officers, who were far from lacking the highest personal courage, into a sense of what military loyalty and subordination required. They made a very different record in 1672 from that of 1666.

Before finally leaving the Four Days' Fight, the conclusions of another writer may well be quoted:—

"Such was that bloody Battle of the Four Days, or Straits of Calais, the most memorable sea-fight of modern days; not, indeed, by its results, but by the aspect of its different phases; by the fury of the combatants; by the boldness and skill of the leaders; and by the new character which it gave to sea warfare. More than any other this fight marks clearly the passage from former methods to the tactics of the end of the seventeenth century. For the first time we can follow, as though traced upon a plan, the principal movements of the contending fleets. It seems quite clear that to the Dutch as well as to the British have been given a tactical book and a code of signals; or, at the least, written instructions, extensive and precise, to serve instead of such a code. We feel that each admiral now has his squadron in hand, and that even the commander-in-chief disposes at his will, during the fight, of the various subdivisions of his fleet. Compare this action with those of 1652, and one plain fact stares you in the face,—that between the two dates naval tactics have undergone a revolution.

"Such were the changes that distinguish the war of 1665 from that of 1652. As in the latter epoch, the admiral still thinks the weather-gage an advantage for his fleet; but it is no longer, from the tactical point of view, the principal, we might almost say the sole, preoccupation. Now he wishes above all to keep his fleet in good order and compact as long as possible, so as to keep the power of combining, during the action, the movements of the different squadrons. Look at Ruyter, at the end of the Four Days' Fight; with great difficulty he has kept to windward of the English fleet, yet he does not hesitate to sacrifice this advantage in order to unite the two parts of his fleet, which are separated by the enemy. If at the later fight off the North Foreland great intervals exist between the Dutch squadrons, if the rear afterward continues to withdraw from the centre, Ruyter deplores such a fault as the chief cause of his defeat. He so deplores it in his official report; he even accuses Tromp [who was his personal enemy] of treason or cowardice,—an unjust accusation, but which none the less shows the enormous importance thenceforth attached, during action, to the reunion of the fleet into a whole strictly and regularly maintained."37