полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 62, No. 386, December, 1847

At present, with a population of twenty-seven millions and a half, we are said to be unable to lay out thirty-five millions annually in the construction of our railways, in addition, to a taxation of fifty millions, – in other words, we cannot raise eighty-five millions a-year without approaching to the verge of bankruptcy!

This, if true, is a very humiliating position, and shows symptoms of a decadence so marked, that we question whether any parallel case can be extracted from history. A population augmented by one-third, say the economists, cannot afford to expend a sum less by ten millions than that which was raised without inconvenience towards the end of the great continental war; and this sum, far from being swallowed up abroad, is usefully employed at home, and is daily assuming the shape of realised capital, yielding a profitable return!

It would follow, then, as a matter of necessity, that we must be infinitely poorer now than we were thirty years ago. Let us see how that matter stands. The net rental of the real property, in England alone, as we find from the assessment tables for the poor-rates, had risen from £51,898,423 in 1815, to £62,540,030, in 1841, and may be estimated at the present moment as augmented by fully one-fourth all over the united kingdom. The personal property, according to Mr Porter, whose accuracy will be unquestioned by free-traders, was estimated at twelve hundred millions in 1814, at two thousand millions in 1841, and has since continued to augment, so that we may fairly assume, that within thirty years, that species of property has been doubled.

Here, then, are grounds for a panic such as that which is now shaking the empire! Here are reasons for leaving the inchoate railways unfinished, dismissing the workmen, and closing our accounts in terror of a national bankruptcy! Really, with such facts before us, we cannot avoid coming to the conclusion that men who use such language as has been too commonly prevalent of late, are either shamefully ignorant, or have a motive for promulgating error.

The expenditure from 1811 to 1815 was, as we have already seen, wholly profitless, and yet it in no way whatever deranged the economy of the country. The vast outlay of capital, which took place at subsequent speculative periods, was a thorough drain upon the country, because it was consumed abroad without return, and gave no employment or stimulus to the home producer. But the railways are investments of a very different description. They do not affect the currency farther than we have noted above, and the remedy for that is simple. By their means the pressure of the famine has been lightened to the poorer classes, and they are not only remunerative to their owners, but of immense benefit to the districts through which they pass. Of three thousand one hundred miles of railway now open, the gross receipts may be taken, in round numbers, as at nine millions annually. Passengers are carried at one half the cost of the old conveyances – so are goods, and time is prodigiously economised. There is, therefore, a positive saving of other nine millions to the inhabitants of the country; and the completion of the works now in progress, will add immensely to, and more than double this. The cheapening of fuel, the transport of manure, and of building materials, and the opening up of mineral fields, hitherto unused and unprofitable, are vast boons to agriculture and trade, and there can be no doubt that the country is deeply interested in their progress.

If it be asked whether the public are able to spare the capital requisite for the completion of those lines without danger or embarrassment to other branches of industry, we think the calculations which we have already given will afford a satisfactory reply. There is no want of capital in Britain, and railway companies will always be able to obtain it at a certain rate of interest. But a currency contracted like ours, and totally incapable of expansion, must inevitably, upon the occurrence of any external accident, derange every branch of our social economy; and as interest rises, so, as a matter of course, will the value of realised property be depreciated. Money is at present the scarcest thing in the market: the capitalist may demand his own price of usance for it; and were this state of things to continue, the results would be far more ruinous than any one has yet anticipated. People are prepared to suffer almost any sacrifice for the maintenance of that credit which is the idol of the Englishman; but the sacrifice must be temporary, not prolonged, else a stoppage becomes inevitable. Neither the merchant nor the manufacturer, nor any other class of men, can afford to conduct their operations at a remunerative rate, while money is exorbitantly high; and all questions even of convertibility shrink into absolute insignificance before the fact, that were money to continue long at eight per cent., the mills and manufactories throughout the country must be shut up, and the public works discontinued. In other words, we would be plunged into a state of anarchy, the ultimate issue of which it would be very difficult to conceive.

No doubt, the railways have had their share in absorbing capital, but what we maintain is, that the capital is abundant and could not have been better employed. The mania of 1845, – for most assuredly enterprise at that time had assumed that extravagant form – was checked by the intervention of Parliament, and a host of crude and unnecessary schemes were at once consigned to oblivion. Should it be said that Parliament did not exercise with sufficient energy its undoubted controlling power, then we shall merely ask who the gentlemen were that, down to the end of the above year, lent their countenance to railway extension? On the 13th of November 1845, we find Sir Robert Peel near Tamworth, with electro-silver plated spade, and mahogany barrow, wheeling away the first sod raised on the line of the Trent Valley railway, and expatiating broadly upon the advantage of "a more direct and immediate communication between the metropolis on the one hand, and Dublin and a great part of Ireland on the other; between the metropolis and the west of Scotland; between the metropolis and that great commercial and manufacturing district of which Liverpool and Manchester are the capitals." Not a word of warning or reproach, or of indication of coming scarcity of money, fell then from the lips of the great author of the Restriction Acts, – measures which were still lying in abeyance to awake for the benefit of the capitalist, and the depression of every other class, long before the sod, so ostentatiously turned over, could be replaced by the permanent rail. What wonder, then, if Parliament, with such examples before their eyes, and such notable testimony in favour of the development of the railway system, should have been slow in foreseeing the danger of too hasty an internal development?

It is also self-evident that during the last few months the frequent and heavy railway calls have added much to our pecuniary embarrassment. In some instances these calls have been by far too recklessly urged; in others it is difficult to see what other course could have been adopted. For whilst, on the one hand, the extreme dearness of money, the utter stoppage of credit, and the impossibility of disposing of property at any thing like its real value, were elements which the directors were bound to consider before using their statutory power; yet, on the other, they were not entitled to overlook the influence which a discontinuance of these works would exercise over the value of the capital already expended, and the great amount of individual and aggregate suffering which would result from the arbitrary dismissal of their labourers. It was the duty of government, while it was yet time, to have stepped in with some precautionary measure. They might have compelled the directors to summon a general meeting of the shareholders previous to the announcement of a call, and have allowed the latter a veto if their interests should have required it; but although proposals to that effect were laid before the Chancellor of the Exchequer, nothing whatever was done, and the increasing panic was heightened by the prospect of peremptory demands.

So much for the railways; by far the most useful class of works which the country has ever undertaken – useful, because, however they may appear to suffer by temporary depreciation, they will, we firmly believe, in the long run, prove amply remunerative; because, in a year of famine, they have given ample employment and adequate wages to a class of men who must otherwise have suffered unexampled deprivation; and because they have opened, and are opening up new elements of wealth, economising time, and facilitating our trade and our commerce. If, under the influence of monetary laws, for which their undertakers were in no wise responsible, they have tended in some degree to increase the common difficulty, let us recollect that the same power which sanctioned them is answerable for the restrictive measures. We have already shown that this new class of works required an increase of the internal currency which was not vouchsafed to it, and the authors of the Banking Act of 1844 are the parties chargeable with that neglect.

In short, to use the words of one of the Rothschilds, who surely is a competent judge, the prosperity of Britain depends, to a great degree, upon the amount of its circulating medium. It is our interest to have money plentiful and to keep it so; and we ought to interpose as few checks as possible to the fair operation of credit. With plenty of money we may command the markets of the world; with a restricted and contracting issue like the present we are comparatively powerless. The great fault of Sir Robert Peel and his coadjutors is, that they seek to confine credit within absolutely intolerable bounds. We may ask, with perfect propriety, whether the colossal fortunes, either of the right honourable Baronet or of his adviser Mr Jones Loyd, could, by any possibility, have been erected without this important element of credit, which they have now combined to prostrate? We apprehend not; and yet in a certain, though not very creditable sense of the phrase, both gentlemen have been true to their order. The new capitalist has the smallest possible degree of sympathy for those who are struggling upwards.

But a fettered currency is not the only evil for which the country demands a remedy. Far more perilous influences have been at work – influences which must be thoroughly probed and exposed at whatever cost of mortification to the dupes, or loss of credit to the schemer. We are willing, even in this age of free trade, when new principles are applauded to the echo and adopted with unseemly precipitation, to incur the odium of maintaining that protection to native industry is the foundation of the prosperity of Great Britain, and that in departing from it we have adopted a wrong course, which, if wise, we shall speedily abandon. Fortunately there is yet time; for the measures to which we allude have been so rapidly productive of their effects, that very little demonstration is required to open the eyes of all men to their baneful nature. Glad indeed shall we be if experience can work conviction.

To prevent all misconception, we beg leave to premise, that we do not enter now into any discussion upon the subject of the repeal of the corn-laws. Our sentiments with regard to that measure have been stated in another place; and although we have seen no cause to alter them, they are unnecessary for our present argument. We have always maintained that the success or failure of that measure in so far as the interest of our agricultural population, no unimportant section of the community, was concerned, could not be immediately tested – that its effects would necessarily be slow, but not on that account the less insidious. Agriculture cannot decline in one day like commerce, and even were it otherwise, extraneous circumstances have since occurred to delay the period of trial. The operation of the tariffs introduced by Sir Robert Peel, with the full sanction of the free-trade party are far more open to comment, and, as we shall presently show, all classes have an interest in the national wager. It is, therefore, the nearer and more engrossing topic of free trade, as affecting commerce and the legitimate wages of the workman, with which we now propose to deal.

Burthened as he is with taxes, poor-rates, and every species of local impost, it would naturally be supposed, that the British manufacturer could hardly be able to compete with the foreigner even in an alien market. But we unquestionably possess great counterbalancing advantages in the abundance of our coal and iron, the skill and energy of our people, and above all, in our accumulated riches. These, if properly managed, are sufficient to enable us to maintain our old supremacy undiminished.

The whole manufactured produce of Great Britain may be estimated in round numbers, and on an average at two hundred millions yearly, whereof three-fourths are consumed at home, and about fifty-one millions or one-fourth of the whole are destined for exportation. The home market, therefore, being by far the most important, is the first province of the manufacturer: the foreign and lesser market, however, is to a certain extent the index of the nation's wealth, because we have a direct interest to see that our exports are larger than our imports, in other words, that we are not annually paying away a greater value than we receive. The home market is certain, or at all events we can render it so if we choose, and the field is constantly increasing. The foreign market, on the contrary, is fluctuating, and over it we have little control. Without an entire change in our colonial system, which, to say the least, would be attended with much difficulty and danger, we must continue to compete with the foreigner abroad on no other vantage ground than that of offering an article equal to or better than his at a smaller price and profit.

It has always been the policy of England, to enlarge this latter field as much as possible, and unquestionably the policy is sound. We give and take with foreign nations as freely as may be, sending out articles which we have produced, and bringing home cargoes for our own consumption. The balance of the two operations must be taken as the estimate of our increasing wealth.

We have paid in manufactures for the specie which constitutes great part of our currency, and which is no product of our own, certainly not less than forty millions. When any portion of that coinage is withdrawn from the country we become so much the poorer, because we are forced to replace the deficit by another exchange of manufactures and that at a diminished price.

The doctrines of the free-trade party may shortly be stated as follows: Sweep away, they say, all restrictions, and do every thing you can to encourage imports, that is, to swell the amount of consumption of foreign produce at home. The inevitable result of this policy will be an increased demand from abroad for the staple commodities which we produce, and an enlarged field for our operations. Therefore reduce the duties levied at the custom-house as much as possible, and let the revenue be raised either directly by income tax, or in some other mode which may not interfere with the progress of trade.

Sir Robert Peel, who has adopted these doctrines, has acted upon them to a certain extent, and the history of his financial proceedings since he last assumed the reins of office is curious and characteristic of the man. He commenced by laying on an income tax, which we were assured was not to last beyond the period of three years, and he promised the public not only to relieve them from the load at the expiry of that time, but to exhibit the national revenue in a more flourishing condition than ever. Proposals so confidently made were cheerfully and even gratefully accepted, for no one could have supposed that there lurked a deception concealed beneath so plausible a scheme.

To the amazement of many, the adoption of an income tax was shortly followed by a reduction of revenue duties, an experiment which has since been repeated. The effect of those reductions was as follows: – the ordinary revenue of the country, at the time when Sir Robert Peel came into power, was within a fraction of forty-eight millions. Ten millions and a half were derived from certain articles, which were subsequently dealt with on free trade principles. These articles under the reduced duty now yield only six millions, whilst the other sources, that have not been tampered with, contribute, as is shown by late returns, forty-one and a half, instead of thirty-seven and a half millions to the revenue. The gain therefore to the country on those items which were left under the operation of our former system was four millions, – the loss upon the articles reduced by Peel was four millions and a half, whereof the greater part has gone into the pocket of the foreigner; and, as Lord George Bentinck well remarked, it is material, with such facts before us, to consider "what would have been the situation of the country if Sir Robert Peel had tried his experimentary hand upon the whole of what are called the ordinary sources of revenue to the country?" There must then have been a huge mistake somewhere. If Sir Robert really believed that in three years he would be enabled to dispense with the income tax, he must have calculated that the reduction of the duties would have the effect of increasing the consumption of imports to such a degree that the revenue would be largely augmented – a result which, we are sorry to say, has by no means arrived. On the contrary, the revenue has fallen off, and the income tax, far from being removed, will, in all human probability, be extended.

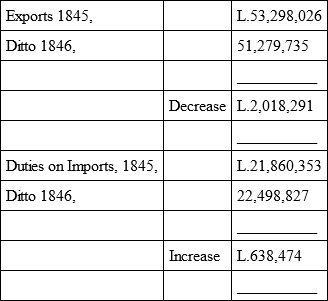

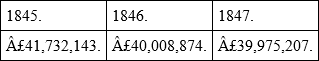

The avowed object of these reductions, which have curtailed our revenue, and saddled us permanently with a war tax, was to increase the amount of our exportations in exchange. If this effect has not been produced, or if there is no likelihood of its being produced within a reasonable period of time, then we are entitled to conclude, from the arguments of the free-traders themselves, that the experiment has been a total failure. We must never lose sight of the fact, that the sure test of free-trade, for which object we have sacrificed our revenue, is augmented export. Let us see how far this branch of the scheme has succeeded. We shall take the exports and imports for the years 1845 and 1846, which will afford a sufficient indication of the manner in which the new tariff is likely to work.

Thus, while the exports are decreasing, the imports are augmenting; we are selling less and buying more, and the foreigner is reaping the profit.

We are fortunately enabled, from the last official tables, issued after the greater part of this article was sent to press, to show what the results of free trade have been since 1846. Several of our friends, who hold ultra liberal commercial opinions, are, as we full well know, slow to conviction, and will be apt to maintain that our experience of the new system up to that period, has not been large enough to justify our condemnation of its failure. Let us then see what testimony 1847 can bear in favour of free trade.

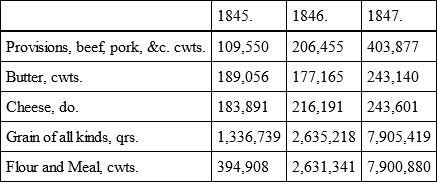

These tables, according to the Economist, a free trade organ of undoubted ability, "continue to show an enormous comparative importation and consumption of all the chief articles which contribute to the daily sustenance of the people, and a marked falling off of those which form the basis of our manufacturing industry, and consequently of our future trade." In other words, whilst we are buying, and buying largely, our articles of provision and immediate consumpt from the foreigner, the supply of the raw material which we can reproduce in the shape of manufactures is falling off. The foreigner has the benefit of underselling us in the home market, and we are losing the power of competition in the markets abroad. The increase of our consumption is most remarkable, and the agriculturist will probably derive but little comfort from the following comparative statements, which show the amount of certain articles of import during nine months of the last three years.

Agricultural Produce Imported Jan. 5 to Oct. 10.

These, we think, are somewhat startling figures. All this has to be paid for by native industry, doubly taxed at present, in order to get back that gold which Sir Robert Peel has practically declared to be the life-blood of the community, and which cannot, under our monetary system, be expended abroad, without depressing credit and prostrating enterprise at home. Let us now see what kind of provision we have laid in for future manufactures – what amount of raw material we have on hand, which, when converted into goods, shall enable us to liquidate this heavy balance, and provide for the future payment of a constantly increasing supply of articles of daily consumpt. We were to be fed by the foreigner, and to work for him, he finding us both the food and materials. Such, we understood, were the terms of the contract, which the free-traders wished the nations of the world to accept. It has been acted upon in so far as regards the food for which we have paid; not so as to the means of payment.

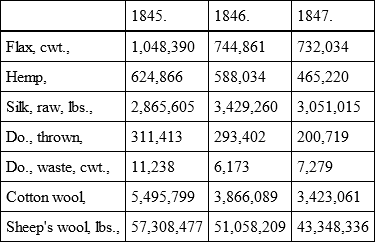

Raw Material Imported Jan. 5. to Oct. 10.

The above table affords us the means of estimating our immediate manufacturing prospects, and we need hardly say that these are any thing but cheering. In no one particular have the prophecies of the free traders been fulfilled. They were wrong in their revenue calculations with respect to the tariff; wrong in their anticipations regarding the import of raw materials; and deplorably wrong in their promises of increased exportation. We hope that Sir Robert Peel will shortly favour the House of Commons, and the country with his explanation of the following mercantile phenomena. It will be listened to with more curiosity than his arguments upon the nature of a pound.

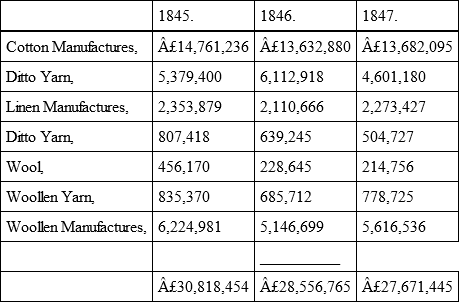

Declared Value of Exports of Home Produce and Manufactures forNine Months. Jan. 5 to October 10.

The general decrease is apparent, but it is necessary to go a little more minutely to work, and inquire into the respective items. It is only by doing so that we can fully understand the true operation of free trade, and the manner in which it is calculated to undermine and ultimately to overthrow the strongholds of our domestic industry. We entreat the earnest attention of our readers to the great decline, which is exhibited in the following staples of export.

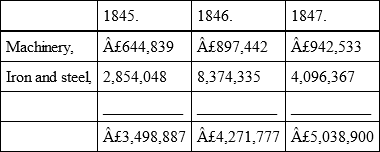

The decline upon these staple commodities of export is so obvious as to need no remark. There is also a falling off, as between 1845 and 1847, in the following exported articles: – Butter, candles, coals, earthenware, glass, leather, copper and brass, lead, tin-plates, soap, and refined sugar. The rise, on the contrary, is upon cheese, fish, hardwares, machinery, iron and steel, unwrought tin, salt, and silk manufactures; of which two items certainly important.

This shows the pace at which manufactures are advancing abroad, and explains but too clearly the reason of the decrease in our staple exports. The product of British industry is declining; and we can only partially redeem the deficit by sending abroad the sinews of our national prosperity. We are in the condition of the artisan whose expenditure exceeds his wages, and who is driven to part with his tools. We are fitting up foreign mills with our choicest machinery, furnishing our opponents with weapons, and yet the free traders tell us that on such terms we can afford to cope with, and to vanquish them!