полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 62, No. 386, December, 1847

The Russian system of banking is rather remarkable. That country, which has lately become one of the greatest gold producers of the world, employs for its own internal use a paper circulation, but the basis upon which that circulation rests, is commonly reported to be a sum of from thirty to forty millions in gold, lodged in the hands and at the disposal of the Emperor. This large amount of bullion had hitherto remained unemployed, but Nicholas, observing that the French funds had, like our own, very much declined, and that bullion was the great desideratum in both countries, determined, with much apparent generosity, to step forward to their rescue. No one save the Czar had any control over the keys which could open this hidden hoard, and with a discernment which does credit to his abilities, he set at liberty "the imprisoned angels," and in return for his unprofitable gold, purchased at most advantageous rates, a deep interest in the national securities of England and of France. The immediate result of that measure is a large accretion of revenue to the Emperor, who is now one of our chief creditors, for whom the manufacturer is bound to toil: the ultimate tendency is yet in the womb of time, but no thinking man will contemplate without alarm the power, which so gigantic and ambitious a state as Russia has thereby gained within the very fortress of our strength.

If we continue in a blind and obstinate adherence to the system of the bullionist party, we shall give the Russian government such opportunities of enriching itself at our expense, as no foreign potentate has ever possessed before. It is quite well known that large purchases of national stock have already been made with the gold of the Muscovite; and therein the autocrat has acted wisely for himself – far more wisely than our enlightened rulers have thought proper to act for us – for he has put out the money to usury, and the basis of the Russian circulation, instead of being profitless gold, is now composed of British and French securities, bought in when the market was at its lowest ebb, and yielding a large return. If our monetary laws should still remain unaltered, and trade should notwithstanding revive, it will be the interest of the Russian, so soon as the funds have reached their culminating point, to sell out largely, and by forcing the gold from the Bank of England, create an artificial scarcity of the precious metal, which, followed as it must be by an immediate contraction of our paper currency, would cause a second panic, and a second prostration of the funds. By buying cheap and selling high – the favourite maxim of the free-traders – he would thus realise an exorbitant profit, and be enabled, should he choose it, to replace the bullion basis of the Russian circulation. But this, as a matter of course, he would not do. The low state of the funds would again offer an irresistible temptation. Fresh purchases of stock, this time made with our own money, would revive public confidence in Britain, and so things would go on, alternately rising and falling without any obvious external cause, but in reality according to the will of a huge foreign fundholder, who, with each successive movement, must be the gainer, whilst we deny ourselves the means of securing the equilibrium of our own monetary transactions at home. Under our present system, the sale or purchase of national securities to the extent of a few millions, has a wonderful effect upon the market. Add the further elements of gold exportation and paper contraction, or the reverse, and the effect becomes prodigious. The purchases already made on the Emperor's account, are reported to have been most heavy, and the process, at the moment when we write, is being again repeated.

This is, in reality, a subject of the gravest nature, and it should not be passed over by the legislature without remark. The Whigs, in all probability, hail such successive importation of Russian bullion, as so many pledges of returning prosperity, not seeing nor understanding the frightful price which we may hereafter be called upon to pay, nor the perils of that artificial fluctuation to which we may be exposed. We have put ourselves, as the experience of the last few months has shown, at the mercy of gold, and consequently at the mercy of any foreign power who can supply us with that coveted commodity; and so we must remain, if the plain sense of the nation does not rouse itself to sweep away the formula of our currency practitioners.

Our advantage from the Russian transaction was only temporary. Again the bullion decreased, and again the screw was tightened. Money was the universal demand, but money became scarcer every day, and the rates of interest increased. Hopeful people, notwithstanding, still adhered to the belief that the pressure was only temporary. The corn-law abolitionist pointed to the luxuriant harvest which was waving plentifully on the fields, and forgetting, with characteristic selfishness, the dogmas which he had so lately enunciated, prophesied a return of manufacturing prosperity from the well-being of that class, which, two years ago, he would ruthlessly have consigned to ruin. But when the plentiful harvest was gathered in, and all fear of another famine, and further bullion drain on that account, was removed, it appeared, to the disappointment of every one, that matters were not likely to mend. The screw was still revolving in the wrong way – prices went down, like the mercury in the barometer before a storm – the man who was rich even in April found himself worse than nothing in October – bills became stationary – the banks were besieged until they closed their doors in despair – and then came the Gazette, with its daily record of disaster.

In truth, we do not envy the situation of ministers during that period; and yet, we hardly know how to pity them. They alone, while the nation was writhing, around them, maintained an attitude of calm complacency. At first, Sir Charles Wood, the most singular optimist of his day, received the different deputations of pallid merchants with assurances that every thing was right. "There is not the slightest occasion for alarm," was the language of this sapient Solon. "Money never was more plentiful in the country – accommodation will readily be granted to every one who has property to show for it – the currency-machine is working remarkably well," – and the Cabinet went placidly to sleep.

But the cries of distress from without became so loud, and the storm of indignation so vehement, that the ministry were at last compelled to exhibit some symptoms of action and vitality. Cabinet councils were summoned – new deputations received – the tale of sorrow was again heard, and this then with decreased disdain. But the perplexity of our rulers was such, or their dissension so great, that they could not devise a plan, whereby even temporary ease might be afforded; and as there is safety in a multitude of councillors, they eagerly inquired into the remedy which each successive sufferer could suggest. These of course were varied and conflicting, but in one point all were agreed – that the restriction act should be suspended. Even then, nothing would force conviction upon the impotent Whigs. They clung to restriction as if it had been the palladium of British credit, nor would they relax their hold of it until they were threatened with force. The crisis was so imminent, that the London bankers were compelled to exhibit the power which they undoubtedly possessed, and to threaten its immediate enforcement. The deposits which they held were immeasurably greater in amount than the quantity of bullion which the Bank of England could give out; and the Lombard Street deputation accordingly intimated that, if government would not suspend the operation of the Act of 1844, they would exercise their statutory right of demanding payment in specie, and expose the whole fallacy of our monetary laws by rendering the Bank insolvent. That threat had more effect than any amount of argument. At the eleventh hour the Whigs yielded, not to remorse, but to necessity, and the Act was accordingly suspended, clogged, however, with a condition, which, instead of relieving the pressure, was infallibly calculated to increase it. The Bank of England alone – for both Peel and the Whigs contend for the monopoly of that establishment – was permitted to over-issue, but with a recommendation, which was in fact an order, that the minimum rate of interest on short bills should be eight per cent, a rate which no merchant or manufacturer can afford to pay. Surely the Bank of England might have been left in this crisis to use its own discretion. But there was another object in view. As the revenue had palpably fallen under the operation of the tariffs, which constitute the measure of free trade already dealt to us, the Whigs were desirous, even in extremis, to make a profit out of the national misery, and it was intimated that the additional gain was not to be appropriated by the Bank, who undertook the risk, but to be handed over hereafter to the government, who undertook the responsibility of suspending the operation of the Act. Under such circumstances, it is clear that real accommodation was almost as difficult to be obtained as before. The suspension, for which Ministry are entitled to no credit whatever, did little actual good, owing to this preposterous condition, beyond relieving the public mind from the apprehension of the frightful nightmare. In fact, the Bank of England did not avail itself of the liberty so granted. It merely raised the rate of discount, and therefore no indemnity is required. The only wise thing which the Cabinet has done, was the summoning together of Parliament at an early day, for assuredly there is need of wiser heads than those possessed either by Lord John Russell or by Chancellor Wood to help us out of the present dilemma.

But where, all this while, is the money? That is the question which every one is asking, and to which very few will venture to give a distinct reply. It is, however, a question which ought to be answered, and we think that there is no great mystery in the matter. The greater part of the money is still in the country, but it is not passing from hand to hand with its usual rapidity, nor in its ordinary equitable proportion. The portion of it which the banks do hold, is, of course, profitless in itself, but yet so far useful that it serves as a basis for paper; the portion which the public hold is fearfully checked in its circulation. This anomaly proceeds from the following causes: We have been forced to make that amount of money, which in ordinary times of unshaken credit was barely necessary to liquidate or balance the ordinary transactions of the community, embrace also the new operations rendered indispensable by the introduction and development of the railway system. We have called forth and created a new source of industry within ourselves, but we have omitted to provide the means by which that kind of industry can be maintained, without trenching upon and abstracting from the supply applicable, as formerly, to our other wants. This is not a question (and herein lies the fallacy of those who are waging such determined war against the railways) of absorption of capital, but of want of the circulating medium. We have been trying, under Peel's guidance, to make that amount of money which barely served eight persons before, suffice now for the extended wants of twelve; and we are perplexed at any scarcity, totally forgetting that we have advanced in the close of the year 1847, to a widely different position from that which we occupied at the commencement of 1844. Gold has become scarcer, altogether independent of the exportation, because there are more persons who require money; and when gold cannot be had, Sir Robert Peel forbids us to trade in paper. There is a minimum supply of money representing that portion of produce which is passing to consumption, without which no country can hope to prosper, and we have already passed that minimum. Hence, the sovereign, though it remains by statute of a fixed value, is of no use as a standard at all, because you cannot measure property by it. You cannot buy coin, except with coin, at any thing like a parity of exchange; and therefore, if the sovereign does not nominally rise, the same effect is produced by the depreciation of property, which, and not bullion or notes, constitutes the real capital of the country. It is a frightful consideration, but nevertheless it is true, that the whole property of this vast country, estimated at something like five thousand millions, is, to all intents and purposes, paralysed for the want of some few millions of extra circulation to supply the extra work we have engaged in, and the extra population we have employed. And it is still more startling to think, that for the want of that circulation, the value of this property is merely nominal and relative, and has been, and is, declining at the rate of many millions a day. In fact, we have at this moment no standard of property, and with such a prodigious decline it may very soon become a serious question, how the revenue of the country is to be raised.

In ordinary times the circulation is extremely rapid. Coin and notes shift from hand to hand without delay, and alternate between the public and the banks; and instances of hoarding are rare. This is well known to be the case both in manufactures and commerce, the business of which is transacted in towns where savings' banks afford the labourer a ready means of depositing his earnings, and so contributing to the passage of the currency. But the railway workman, who is now an important personage in the state, possesses no such facilities. He is essentially a wandering character, shifting his ground and place of abode to accommodate himself to the scene of his labour, and he either does not understand, or he will not avail himself of, the ordinary channels of deposit. Many of this class have undoubtedly saved money out of their ample and remunerative wages, but these savings are just so many hoards which in the aggregate have an injurious effect upon so contracted a currency as ours. So far from the immense expenditure of capital upon the railways being a necessary drain upon the currency, it would in truth, if the wages of labour were rapidly exchanged for produce, have greatly facilitated the circulation; but the wages being hoarded, and the gold and notes kept out for an absolutely indefinite time, a new element of confusion has been introduced. It is not merely difficult but absolutely impossible to calculate how much of the circulating medium has been in this way withdrawn. We are inclined, from the testimony of persons engaged in the construction of railways, and intimately acquainted with the habits of the workmen, to place it at a large figure. And when we recollect that the wages of nearly 600,000 men so employed have been for more than three years greatly higher than those of the common agriculturist, we might be justified in making an assumption which assuredly would startle the reader. The hoarding of small sums, when that practice becomes general, has a most extraordinary effect upon the currency, as every one who looks at the amount of surplus wages invested in the savings' banks must acknowledge: and as we cannot force any portion of our population to deposit, we are bound to take care that their ignorance, or erroneous ideas of security, shall not be allowed to operate banefully upon so important a matter as the circulation. The money thus hoarded is not lost, but it is temporarily suspended, and its hoarding becomes an evil of no common magnitude, which pleads strongly for an augmented issue.

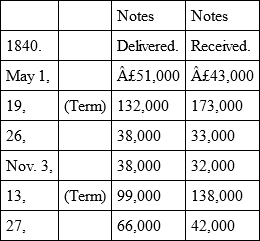

The Scottish and Irish banking acts of 1845, which were introduced, and in spite of all national remonstrance, forcibly carried through by Sir Robert Peel, ostensibly for the sake of uniformity, have very much deranged the currency of England, by locking up a large portion of the coin. We need not repeat here, for the fact is notorious, that sovereigns, except to a merely fractional extent, are not current in Scotland, and are received with absolute distrust. Nobody wants them; and the note of a joint-stock bank is at all times a more acceptable tender. But the acts which forced the banks to retain an amount of bullion for all paper issued beyond their average circulation, were based upon a false principle, which, three years ago, when the first aggressive step was taken, we urged upon the consideration of government, but unfortunately without success. The average circulation of the banks over the year was not a fair calculation. Twice a-year, as we have already remarked, all of the banks in Scotland required to augment their issues in order to meet the term payments, and notwithstanding Sir Robert Peel's enactments, the same necessity exists. This will be better understood by comparing the amount of notes delivered and received by the Bank of Scotland in exchange with other banks on the term-days, with the like exchange during other periods of the same months.

There is also, we ought to remark, a considerable rise of the issue during the weeks which immediately precede and follow these terms. Now the same fluctuation occurs in every one of our banks, which about term-time are called upon to furnish accommodation to an extent of nearly three times their ordinary issue. No allowance was made in the act of 1845 for this inevitable expansion, and consequently the Scottish banker is forced to do one of two things. Either he must permanently hold during the whole year a much larger amount of gold than is necessary to satisfy the legal requirement for his ordinary over issue, or he must provide gold from London twice a-year, in boxes, which arrive sealed at his place of business, to be returned within a fortnight with the seals unbroken! Such is part of the absurd and ridiculous machinery, which it has been the study of Sir Robert Peel during half a lifetime to elaborate; and the practical result is, that nearly the whole of the gold required to balance the transactions of Scotland for the term weeks, is withdrawn from the ordinary circulation. Indeed, gold to the extent of the whole term payments would be required, save for the proviso in the act which allows the circulation to be calculated at the end of every week; but, as we have said already, the rise is gradual, not being limited to the term days, and for two weeks at least, the circulation, that is, the amount of the notes issued, is much larger than the ordinary average of the year. It thus follows that the bullion to represent the term issues, must either lie in the coffers of the Scottish banks, or in the hands of their correspondents in London, ready to be sent down whenever the appointed seasons shall arrive!

Here then is another drain, or rather suspension of a large proportion of our circulating medium, which has been most unnecessary. The Scottish public suffers from the want of accommodation; the Scottish banker suffers from the enormous expense which this juggle entails upon him; and the Englishman suffers by the gold which was formerly his currency, being kept in pawn at the period when he requires it most. Besides, it is well worthy of remark, and known to every banker here, that the circulation of Scotland during the year when the average was taken, had been reduced to its very lowest possible ebb. The frugality of the country, the extension of the branch banks, the efficient mode of interchange, and, above all, the interest allowed upon all deposits, were the causes which had led to this; and it seems now to be universally admitted by all writers on currency, that a more admirable and perfect system could not have been invented by the ingenuity of man. All this, however, has been overturned by Sir Robert Peel, to the great injury of Scotland, and the positive detriment of England; and had he succeeded in pushing his bullion theories further, and replaced the one pound note circulation in this country by the sovereign, a double amount of calamity would have been inflicted at the present moment. We entreat the attention of the English currency-reformers to this; for they may rely upon it, that the abolition and total repeal of the Scottish and Irish banking acts of 1845, without any new legislative enactment at all, would be an inestimable boon, not only to these countries, but to England, which is now compelled to furnish gold, which is neither used nor required, and so to cripple and impede materially her own circulation.

The hoarding, therefore, by the railway labourer, and the reserves nominally kept for the use of Scotland and Ireland, will account for the disappearance of a large proportion of the coinage from the circle. These are only primary causes of the scarcity, yet they are material elements in inducing that want of confidence, which, as we have already said, is the mighty evil that is now oppressing and bearing us to the ground. Whenever want of confidence is manifested, the circulation must farther contract. Joint-stock and private bankers, for their own security, maintain a large reserve of Bank of England paper and bullion, and there are always terrified persons enough to occasion a partial run for gold. We do not charge the bankers with impolicy in thus abetting the general contraction. Situated as they are, it becomes a matter of necessity to look to their own interests in preference to the accommodation of the public; but it is right that the public should be made aware of the mischief which is caused thereby. The results are surely patent to the apprehension of all. In proportion as circulation contracts, interest rises; and the wary capitalist, foreseeing the advent of the dark hour, realises while he can, in the knowledge that his money hereafter, when things are at the worst, will enable him to drive the most exorbitant and usurious bargains. This is the class of men for whom Peel has uniformly legislated, and it is they who, under our present miserable monetary system, must ultimately absorb the hard-won earnings of thousands of their fellow-creatures. They are not enemies of speculation – on the contrary, they fatten upon it. They strive for a time to stimulate industry to its utmost, and then use every exertion to depreciate the industrial result. Hard times are their harvest, and prosperous years their seed-time; and never, so long as they can hold it, will they relax their pressure of the screw.

The sacrifices of good solid property which have been made during the last few months, and which were occasioned solely by the baneful contraction of the currency, have been positively enormous. It is common to hear the capitalists remark with a sneer, that such is the inevitable result of over-trade and over-speculation. It needs no prophet to tell us, that the man who has not a farthing in the world can neither buy nor sell; and we admit that, in the present monetary convulsion, as in every other, much ripe fruit has fallen to the ground. But we deny that present prices have been the result of over-speculation. We maintain that, sooner or later, the country must have been brought to this unhappy condition, simply by the operation of these currency restriction laws; and if we are insane enough to allow them to continue, we shall inevitably be plunged into the same abyss, even though temporary measures should effect a temporary rally. It is calculated, and with great appearance of probability, that the depreciation which has already taken place, is larger than the whole amount of our national debt!

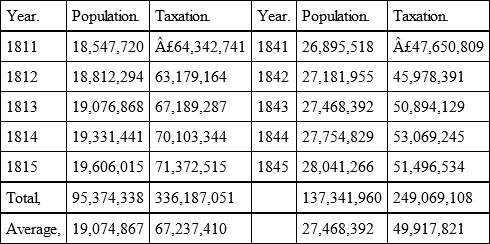

It is necessary that we should grapple boldly with the proposition, that over-speculation in our home works, that is, the expenditure upon the railways in progress, is the cause of our present embarrassment. In order to do this, we must have recourse to statistics, and we shall now lay before our readers tables exhibiting the state of our revenue and population, for two periods of five years each.

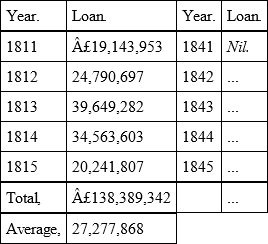

But, in addition to the taxes which were levied during the years 1811-15, there were loans contracted as follows:

We thus arrive at the following results. About thirty years ago, with a population of nineteen millions, we were able to raise an annual sum of ninety-four and a half millions of pounds, whereof more than one-half was expended abroad in subsidies and the maintenance of an army, and little or none of it was returned in the shape of capital to this country.