полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 68, No. 417, July, 1850

We have nothing to say to the arguments of the noble Viscount – however singular these may appear to persons of ordinary understanding – we merely refer to his conclusion, which we think is plain enough, to the effect that free importations could not materially lower prices. Nay, we could extract from the speeches of Sir Robert Peel himself, passages which would go far to show that he entertained the same opinion, notwithstanding the extreme wariness which he exhibited when challenged by Lord George Bentinck to state his views as to the probable effects of the change on the value of agricultural produce. Well, then, if this be the case – if there was actually a strong conviction in the minds of the leading men who supported the repeal of the corn laws that the expressed fears of the agricultural party were unfounded – are we not entitled now to require that the question should be brought to a very narrow issue indeed? So far as experience has gone, our calculations have proved right – theirs entirely wrong. We maintained that, in consequence of the removal of protective duties, the price of grain in this country would decline to a point far below the cost of production; they averred that nothing of the kind would happen. Nearly a year and a half has elapsed since the new system came into full operation, and the general averages of wheat throughout the country have fallen, and have remained for many months below 40s. per quarter. In spite of the accurate and veracious information of writers in the Economist and other Ministerial prints, who have been assuring us, for a long period of time, that the whole available supplies of grain have been pumped out of the Continent, importations continue undiminished. In May 1850 we receive from abroad the equivalent of a million quarters of grain; France pours in her flour, to the panic even of our millers; and, instead of diminution, there are unmistakeable symptoms of a greater deluge than before. Now, if the Free-traders, in or out of Parliament, are honest in their views – as many of them, we believe, undoubtedly are – they are bound to tell us how far and how long they intend this experiment to last? Of course, if it is no experiment at all, but an absolute rigorous finality, there is no need of entering into discussion. If everything is to be sacrificed for cheapness, let cheapness be the rule; only do not let us behold the anomaly of the advocates of that system prophesying a rise of prices as a general boon to the country. If otherwise, surely some tangible period should be assigned for the endurance of this experimentum crucis. We entirely coincide with Lord John Russell in his dislike to vacillating legislation, and we have no wish whatever to precipitate matters. We think it preferable, in every way, that the eyes of the country should be opened to a sense of its true condition by a process which, to be effectual, cannot be otherwise than painful. But we are greatly apprehensive of the consequences which may arise ere long, from the obstinate refusal of Ministers to give the slightest indication of their intentions, supposing that the present prices shall continue; or to indicate what relief, if any, can be given to the industry of the nation.

As to the permanent nature of the fall under the operation of the present law, we entertain not the slightest doubt. There is no one symptom visible of its abatement; on the contrary, the experience of each succeeding month tends to fortify our previous impressions. The decline in the value of cattle is as great as in that of cereal produce. We have already, in a former paper, had occasion to state the extent of that fall down to the commencement of the present year: the accounts received of the state of the Dumbarton market, held in the beginning of June, are still more disastrous than before. Throughout a large portion of the Scottish Highlands – we do not know, indeed, whether we are entitled to make any exception – black cattle, the staple of the country, will not pay the expense of rearing. The enormous importation of provisions from America is annihilating this branch of produce, with what compensating benefit to the nation at large, it would be difficult for an economist to explain.

This is a state of matters which cannot continue long without manifest danger even to the tranquillity of the country. It is quite plain that, at present rates, agriculture cannot be carried on as heretofore in Great Britain. The farmer has been the first sufferer; the turn of the landowner is approaching. Let us illustrate this shortly. There must be, on an average of ordinary years, a certain price at which wheat can be grown remuneratively in this country. Sir Robert Peel, no mean authority on the subject, has indicated his opinion that such price may be stated at or about 56s. per quarter. Mr James Wilson, rating it somewhat lower, fixes it at 52s. 2d. Let us suppose, that wheat for the future shall average over England 39s. per quarter, and that the produce of the acre is twenty-four bushels, the loss on each acre of wheat hereafter raised will be, according to Sir Robert Peel, £2, 11s. – according to Mr Wilson, £1, 19s. 6d. What deduction of rent can meet such a depreciation as this? Excluding Middlesex, which is clearly exceptional, the highest rented county of England, Leicester, is estimated at £1, 14s. 10d. per acre; Warwickshire, at £1, 11s. 6d.; and Lincolnshire at £1, 8s. Haddington and Fife, the highest rented counties of Scotland, are estimated at £1, 5s. 6d. per acre. This of course includes much land of an inferior description; but we believe that, for the best arable land, an average rent of 40s. per acre may be assumed. In that case, supposing the whole rent to be given up, the farmer would still be a loser by cultivation, if Sir Robert Peel is correct in his figures.

Without presuming to offer an opinion as to the accuracy of either of the calculations submitted by these two Free-trading authorities, we think it is plain that the more favourable of them, taken in connection with present prices, is appalling enough to the agriculturist, whether he be landlord or tenant. We shall see, probably in a month or two, whether it is likely that even these prices can be maintained. We are clearly of opinion that the price of corn in this country must fall to the level of the cheapest market from which we can derive any considerable supplies; and in that case it is quite as likely that we may see wheat quoted at 32s. or 33s., as at 39s. or 40s. But the matter for our consideration is, that, ever since the repeal of the corn laws, the market price of grain has been greatly below the cost of its production; and that there are no symptoms of any amendment, but obviously the reverse.

The inevitable result of the continuance of such a state of matters is too clear to admit of argument. The land must go out of cultivation. The process may be slow, but it will be sure. It may, doubtless, be retarded by remissions of rent not sufficient to cover the farmer's losses, but great enough to induce him to renew his efforts for another year with the like miserable result; until at length the tiller of the soil is made bankrupt, and the landowner occupies his place. We can hardly trust ourselves to depict the effect of such a social revolution. All the misery which has been already felt – and that is far greater than our rulers will permit themselves to believe – would be as nothing compared with the calamitous consummation of Free Trade.

Yet it is towards that point that we are rapidly tending. Some of the fierce and more plain-spoken Radical journals are so far from contradicting our views, that they openly rejoice in the havoc which has been already made, and in the wider ruin which is impending. They say plainly, looking to the funds, that they see no method of escaping from the domination of the moneyed interest, except through the prostration of the landlords. Their meaning is quite distinct and undisguised. They want to get rid of the national debt, by reducing the value of produce so low, that the usual amount of taxation cannot possibly be levied; and their scheme, however nefarious, is by no means devoid of plausibility. There can be no doubt that the Currency Act of 1819 has operated most injuriously upon the industry of the nation, by enhancing the value of the claims of the creditor; and that these claims, along with the necessary expenses of government, must be paid, ante omnia, from the industrial produce of the year. The cheapening process, therefore, is one directly antagonistic to the maintenance of taxation. The anomaly in legislation of forcibly reducing the value of produce, and yet maintaining stringently an artificial standard of taxation, has been reserved for our times; yet, strange to say, though its effects are visible and confessed, few persons have courage or patience enough to grapple with the difficulty. Free Trade and a Fettered Currency are things that cannot possibly co-exist for any length of time; and our sole surprise is, that any statesman could be shortsighted enough to attempt to reconcile them. Taken singly, either of them is a great evil to a country situated like ours – taken together, they become absolutely intolerable. But we have no wish, at the present time, to depart from the point before us. We are merely taking the evidence of adversaries, to show that our views as to the position and prospects of the great productive classes of Britain are so far from exaggerated that they are acknowledged by the most strenuous advocates of Free Trade. The fundholder, nevertheless, may derive a useful lesson from these financial hints, which indicate an ulterior purpose.

Such is the state of the agricultural interest throughout the three Kingdoms at this moment, and such are the prospects before us. The evidence, albeit not taken before a committee of either House of Parliament, is too unanimous to admit of a doubt; county after county, district after district, parish after parish throughout England, have testified to their melancholy condition. The Times may talk of mendicity, and the Economist may trump up figures to show that the farmers ought to be making a profit even at present prices; but neither irony nor fiction can avail to discredit or pervert facts so well authenticated as these. Of these facts parliament is fully cognisant – not only from the individual knowledge of members as to what is passing abroad – not only from the sentiments expressed at many hundred meetings, independent of the great demonstrations lately made at London and Liverpool – but from the petitions which have been presented to both Houses, praying for a reversal of that policy which has proved so detrimental to the interests of a large section of her Majesty's subjects. Yet still Parliament is silent, and the first Minister of the Crown refuses to sanction that appeal to the country, which the exigency of the case would seem to require, and which has been resorted to on occasions far less peremptory and pressing than this.

Let us not be misunderstood. Our wish simply is to record the fact of such silence and refusal, – not to be rash in censure. We cannot, and do not forget the peculiar circumstances connected with the last general election – the political tergiversation which preceded it, the hopes and expectations which were then entertained by many, as to the working of the new system, – or the disorganisation of parties. Even the most strenuous opponents of the Free-Trade measures, since these had passed into a law, however iniquitously carried, were desirous that the experiment should have a fair trial, and that it should not be impeded in its progress, so long as, by the most liberal construction, it could be held to justify the anticipations of its authors. Many names of great weight, influence, and authority were found among the roll of those who consented to the new measures; and it was most natural that, throughout the country, a number of persons should be found willing to surrender their own judgment upon a matter yet untried, which had received so creditable a sanction. Therefore it was that the majority of members returned to the present House of Commons were Free-traders, bound to the system by the double ties of previous conviction and of pledge; and though recent elections, as well as the alarming posture of affairs, have contributed materially to alter the position of the two great parties in the House, it would be unreasonable as yet to look for a change, in a body so constituted, at least to that extent which a reversal of the adopted policy must imply.

Neither can we rationally expect, that Lord John Russell will be forward to recognise a failure, where he confidently anticipated a triumph. We believe him to have been, far more than Sir Robert Peel, the dupe of those random assertions and presumptuous calculations which were thrust forward by men utterly unfit, from their previous habits and education, to pronounce an opinion upon subjects of such magnitude and intricacy. We should not be surprised if, even now, his Lordship had some lingering kind of faith in the prophecies of the member for Westbury. Men are slow to believe that the ground is crumbling from below their feet; that the political scaffolding which they assisted to rear has been pitched in a marshy quagmire. Self love, and that kind of pride which is so nearly allied to conceit that it often assumes the form of obstinacy, stand woefully in the way of recantation; and moreover in the present instance to recant is equivalent to resign. We remember well the profound and sagacious remark of Sir Walter Scott, that "the miscarriage of his experiment no more converts the political speculator, than the explosion of a retort undeceives an alchymist." Lord John Russell in all probability is not yet prepared, from conviction, to revise his opinions on a question in which he is so deeply committed. He has a majority in the House of Commons, and, according to the forms of the constitution, so long as he can command that majority, he is entitled to persevere. It is well that our friends, whatever pressing cause they may have for their impatience, should remember these things; and not be too forward in pressing wholesale accusations, either against a Parliament chosen under such peculiar circumstances, or a Minister who is simply adhering to the course long since avowed by himself, and acted on by his immediate predecessor. We may regret, and many of us do unquestionably most bitterly feel, the anomalous position in which we are placed. A more cruel, a more galling thought can hardly be imagined than the conviction which is very general abroad, and which is also ours, that the present Parliament does not represent the feelings or the desires of the people; that it is not consulting their welfare or protecting their interests; and that the duration of that Parliament alone prevents a vigorous and successful effort in the cause of British industry. Yet still, while we feel all this, let us not be unjust to others. We cannot coerce opinion. We cannot force honourable members at once to retrace their steps, or to give the lie to their acknowledged pledges. We cannot complain of open wrong if Ministers decline to accept our voices, in lieu of the voices of those whom we formerly sent as representatives. Their answer and vindication lies in the fact of their Parliamentary majority. Why Parliament should thus be placed in direct antagonism to the country, is a very different question. We need not go far in search of the reason. It is the direct consequence of that policy which Sir Robert Peel thought fit to adopt, not with regard to the abstract measures of Free Trade, but for the carrying of these measures into effect, without an appeal to the country, and by means which proved how closely deceit is allied to tyranny. Upon his head, if not the whole, at least the primary responsibility rests. He has accepted it, and let it abide with him. And let no man affirm that, in saying this, we are prolonging any rancorous feeling, or seeking to rub a sore which by this time should be wellnigh healed. The time for indignation and anger, if injury coupled with perfidy can ever provoke such sentiments, is not yet past; it is now in its fullest force. Had Sir Robert Peel acted as he ought to have done – had he played the part of a British statesman, sincerely desirous that in a matter of such magnitude the will of the country should be respected – the present Parliament, whatever might have been its decision as to Free Trade or Protection, would at least have represented the wishes of the electoral body; and if subsequent events had shown that these wishes were more sanguine than wise, the error would have been a national one, and no weight of individual responsibility would have been incurred. As it is, we are not only justified, but we are performing our duty, in indicating the real and sole originator of our present difficulties; and without wishing in any degree to trench upon his secret sources of consolation, we can hardly imagine that he will derive much comfort from the knowledge, that his tortuous policy has deprived the people in the hour of need of their best constitutional privilege and shield – the sympathy and co-operation of that House which is emphatically their own, and which, to the great detriment of the state, must lose its moral power the moment that it ceases to represent the will, and to protect the interests of the Commons.

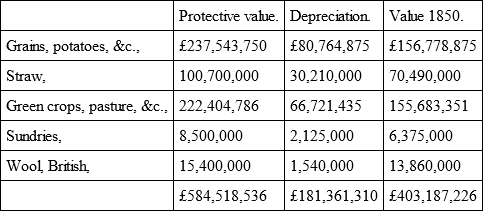

We are well aware that such reflections as these can bring but sorry comfort to the farmers. Their situation is one of unparalleled hardship, unrelieved by any consideration which can make the case of other sufferers more tolerable. We fully admit the vast extent of the powers which, since the Great Revolution, are held to be vested in Parliaments. We cannot gainsay the doctrine that these powers may, on occasion, be exerted to the uttermost; but we say, after the most careful and thoughtful deliberation, that the proceedings of the legislature with regard to the farmers of Great Britain are irreconcilable with the principles of justice, with the sacred laws of morality, which no legislative resolutions can abrogate or annul. The farmers are entitled to maintain that, in so far as regards them, the public faith has been broken. Such of them as hold leases had a distinct and unqualified guarantee given to them by the protective laws; and the allegation that the substitution of the sliding-scale for a fixed duty acted as a release for all former Parliamentary engagements, is a quibble so mean and wretched that the basest attorney would be ashamed to use it as a plea. The whole of the farmers' fixed and floating capital, estimated at the enormous sum of five hundred millions sterling, has been laid out on the faith of Protection; and yet when that Protection was furtively and treacherously withdrawn, no measure was introduced for the purpose of relieving them from engagements contracted under the older system, which were obviously incompatible with the lowered prices established by the formidable change. The public, we are afraid, are not aware of the extent of that depreciation which is still going on, and which already exceeds the whole annual value of the manufacturing productions of Great Britain. We borrow the following table from a late pamphlet by Mr Macqueen entitled, "Statistics of Agriculture, Manufactures, and Commerce, drawn up from Official and Authentic Documents;" and having tested it by every means in our power, we have no hesitation in adopting it. It is, in truth, a fearful commentary on the rashness and folly of our rulers.

COMPARATIVE VALUES OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCE.

But this is not all. We have still to deal with the depreciation or diminished value of the farmers' fixed capital, invested in live stock, &c., which at the rate of 25 per cent, (a most moderate calculation, and below the mark in so far as Scotland is concerned,) shows a loss on £504,833,730 of £126,208,432 additional!

We put forward the case of the farmers thus prominently, because, in addition to the great public wrong which has been done to them, they have serious reason to complain of the general apathy of the landlords. We do not allude to the part which the landowners took in 1846. We believe that the majority of them were sincerely disgusted by the conduct of the men who had climbed into office on their shoulders; and that they loathed and despised in their hearts the treachery of which they were made the tools. We know, moreover, that a great many of them abstained from taking part in the election of 1847, not being able to see their way through the political chaos in which we were then involved, and having, naturally enough, lost confidence in the probity of public men, and despairing of the remodelment of a strong constitutional party. Such things were, perhaps, inevitable; and it may be argued with much show of reason, that no better line of conduct was open to the landlords, and that they did wisely in reserving themselves for a more favourable opportunity, when experience, that stern and unfailing monitor, should have exposed to the Free-traders the falsity of their wild expectations. But it is impossible for them now to plead that the opportunity has not arrived. The experiment has been made, and has failed – failed utterly and entirely, if the practical refutation of the views advanced by all its leading advocates is to be considered as equivalent to failure. The current of reaction has set in strong and steady, not only in the counties, but in the towns; not only among those who, from their position, must be the earliest sufferers, but among those who are connected with the trade and general commerce of Britain. The disorganised party has rallied and is reformed under leaders of great talent, tried skill, and most assured loyalty and honour. How is it that, in this posture of affairs, any considerable section of the landlords is still hanging back? Why is it that they do not place themselves, as is their duty, at the head of their tenantry, and enforce and encourage those appeals to public justice, and to public policy, which are now making themselves heard in every quarter of the kingdom? We confess that we are at a loss to know why any apathy should be shown. The conduct of the tenantry towards the landlords has been generous and considerate in the extreme. They were invited, in no equivocal terms, to join their cause with that of the Free-traders and financial reformers; and they were promised, in that event, the cordial assistance of the latter towards the adjustment of their rents, and the equalisation of their public burdens. We venture not an opinion whether such promise was ever intended to be kept. Still it was made; and no effort was left untried to convince the farmers that their cause was separate and apart from that of the owners of the land. Their refusal to enter into that unholy alliance was most honourable to the body of the tenantry, and entitles them, at the hands of the proprietors, to look not only for consideration and sympathy, but for the most active and energetic support. Very ill indeed shall we augur of the spirit and patriotism of the gentlemen of England, if they longer abstain from identifying themselves universally with a movement which is not only a national one, in the strictest sense of the word, but upon which depends the maintenance of their own interests and order. Surely they cannot have been so dull or so deaf to what is passing around them, as not to be aware that they were especially marked out as the victims of the Manchester confederacy! These are not times in which any man can afford to be apathetic, nor will any trivial excuse for languor or indifference be accepted. Exalted position, high character, the reputation for princely generosity, and the best of private reputations, will be no apology for inactivity in a crisis so momentous as this. Organisation, union, and energy are at all times the chief means for insuring success; and we trust that, henceforward, there may be less timidity shown by those who ought to take the foremost rank in a contest of such importance, and who cannot abstain longer from doing so without forfeiting their claim to that regard which has hitherto been readily accorded them.

It will be observed that, as yet, we have put the case for Protection upon very narrow grounds. We have shown that, so far as the agricultural body is concerned, Free Trade has proved most injurious, and that it cannot be persisted in without bringing downright ruin to that section of the community. If we had nothing more to advance than this, still we should be entitled to maintain that enough has been adduced to show the necessity of retracing our steps. The annihilation of such an important body as the agriculturists of Britain, implies of itself a revolution as great as ever was effected in the world; and to that, assuredly, if the agriculturists stood alone, they would not tamely submit. When Mr Cobden or his satellites addressed the people of Manchester, through their League circulars, to the following effect, "If the Americans will only put down their monopolising manufacturers, and we put down our monopolising landowners here, when our election time comes, we will lay the Mississippi valley alongside of Manchester, and we will have a glorious trade then!" – and again, "Our doctrine is, let the working man ply his hammer, or his spindle, or his shuttle, and let the Kentucky or the Illinois farmer, by driving his plough in the richest land on the surface of the earth, feed this mechanic or this weaver, and let him send home his produce in exchange for the products of our operatives and artisans" – they seem to have forgotten the temper and mould of the men with whom they proposed to deal so summarily. It is not quite so easy to expatriate three millions of able-bodied men; nor do we opine that a power morally or physically adequate to the task of such removal exists in the manufacturing districts. But, in reality, of all idle talk that ever issued from the lips or the pen of an inflated demagogue, this is the silliest and the worst. It presupposes an amount of ignorance on the part of his audience anything but flattering to the calibre of the Manchester intellect: indeed we hardly know which is most to be admired – its intense and transparent folly or its astounding audacity. The home trade is a thing altogether kept out of account in the foregoing splendid vision of a calico millennium. Mr Cobden, it will be seen, contemplates no home consumption, except in so far as the operative may provide himself with his own shirtings. The whole production of Britain is to be limited to manufactures; the whole supplies are to be derived from the hands of the reciprocating foreigner!