полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 64, No. 393, July 1848

In this state was the feeling of the country at large when the general elections came on, accompanied by all the violence of party manœuvre to support the principles of ultra-republicanism, advocated by the unscrupulous minister of the nation; but all these efforts tended only to indispose it still more, and to call forth, in spite of the desperate opposition made, its sense in favour of respect of property, order, and moderatism of views in the republic, if republic there was to be. As is well known, an immense majority of those men of moderate principles, whom all the ill-judged and hateful efforts of the violent and reckless republicans at the head of affairs had so greatly contributed to form into a decided, self-conscious, and compact party of opponents, was returned to the Assembly. Most of the leading men of the liberal party under the former dynasty, who had stood forward as friends of progressive reform, but not as opponents to the constitutional monarchy principle, were likewise elected, with great majorities, by the suffrages of the people. The country declared its will to be against the views of the principal and stirring influence which emanated from the reckless man who governed the interior affairs of the country in the capital. But it did not forget, at the same time, and it still bears an inveterate grudge to the violent agents of that ultra-republicanism, chiefly concentrated in Paris, who had filled the country with disorder, tumult, terror, and, in some cases, bloodshed, by the atrocious and outrageous means it placed in the hands of a riotous mob to overawe them, and sway the direction of the elections, and by the base manœuvres employed to attain their ends. It does not forget the despotism of certain commissaries, who, after having their own lists of ultra-democratic candidates, whom they intended to force down the throats of the electors, printed, threatened the printer, who should dare to print any other, with their high displeasure, and caused them to shut up their press. It does not forget the seizure of those papers that proposed moderate candidates, with every attempt to strangle in practice that liberty of the press which was so clamorously claimed in theory. It does not forget the voters' lists torn from the hands of voters by a purposely excited mob. It does not forget the odious manœuvre by which agents were largely paid and sent about to cry "Vive Henri V." in the streets of towns, in order to induce the belief in a Bourbonist reactionary party, and thus rouse the passions and feelings of the flattered and declamation-intoxicated mob against the moderates, regardless of the consequences – of the animosity and the bloodshed. It does not forget the intimidation, the threat of fire and sword, the opposition by force to the voting of whole villages suspected of moderatism – the collision, the constraint, the conflict, the violence. It does not forget all this, nor also that it owes the outrage, the alarm, and the suffering, the ruin to peace and order, to commerce, to well-being, to fortune, to that central power which turned a legion of demons upon it, in the shape of revolutionary emissaries and agents. It forgets still less the scenes of Limoges, where a mob were turned loose into the polling-house to destroy the votes, drive out the national guards, disarm these defenders of order and right, and form a mob government, to rule and terrorise the town, while Master Commissary looked on, and told the people that it did well, and laughed in his sleeve. It forgets still less the fury of the disappointed upon the result of the elections, their incitements to insurrections, their preachings of armed resistance for the sake of annulling the elections, obtained, it must never be forgotten, by universal suffrage, in face of their culpable manœuvres: the emissaries again sent down from the clubs, and with an apparent connivance of certain ultra-members of the government, from the charge of which, now more than ever since the conspiracy of the 15th May, they will scarcely be able to acquit themselves: the efforts of these emissaries to make the easily excited and tumultuous lower classes take up arms, and the bloody conflicts in the streets of Rouen: the complicity of the very magistrates appointed by these members of the government – the terror and the bloodshed, and then the cry of the furious ultras that the people had been treacherously assassinated – the conspiracies and incendiary projects of the vanquished at Marseilles, the troubles of Lisle, of Amiens, of Lyons, of Aubusson, of Rhodez, of Toulouse, of Carcassonne – why swell the list of names? – of almost every town in France, all with the same intent of destroying those elections of representatives which the country had proclaimed in the sense of order and of moderatism. It forgets still less the dangers of that same 15th May, when the government was for a few hours overthrown, by the disorderly, the disappointed, the discontented, the violent ultra republicans, the conspirators of Paris, – when some of those, who had been formerly their rulers, were arrested as accomplices, and others still in power can scarcely yet again avoid the accusation and conviction of complicity.

All the other troubles of this distracted country, since the revolution of February, may be passed over – the ruin to commerce, the poverty, misery, and want, the military revolts excited by the same emissaries to cause divisions in the army, as likewise the unhappy troubles of Nismes, where the disturbances took a religions tendency – as a conflict of creeds between Roman Catholics and Protestants, rather than a political or even a social character, – although they still bore evidence of the disorder of the times and the disturbance of the country. The elections, then, contributed more powerfully than ever to the fermentation, the discontent, the mistrust, and the ill-will of the country.

In this state of France, with the feeling of impatient jealousy and irritation against tyranny and despotism expressed by the departments towards the capital, with the evident disunion between the provinces and Paris, what are likely to be the destinies of the Republic hereafter? Again it must be said – who can tell, who foresee, who predict? The Republic has been accepted, and is maintained, from a love of order and the status quo: but there is no enthusiasm, no admiration for the republican form of government throughout the country at large; there is, at most, indifference to any government, whatever it may be, provided it but insure the stability and prosperity of the country. If an opinion may be hazarded, however, it is, that the danger to the present established form of things will not arise so much from the conflict of contending parties in the capital, as from the discontent, disaffection, jealousy, and, perhaps, final outbreak and resistance of the departments. Terrorism has had its day; and it would be difficult, if not impossible, to apply the system once again to the country in its present state. What other means will the violent possess – what coercive measures, if, when parties come to an issue, the wearied and disgusted country should rise to protest against the disorders of Republican Paris? There seem at present to be none. The result of such an outbreak would be inevitable civil war. The strong instance before alluded to, of the determination of the departments to assert a will of their own, was given in a very striking manner in the affair of the 15th May. One of the conspirators got possession of the electric telegraph at the Home Office, and sent down despatches into all the provinces, to inform the country that the Assembly was dissolved, and the new government of the ultra-anarchist party had taken the reins of power. Instead of being awed into submission as heretofore, instead of calmly and resignedly accepting the fait accompli as was their wont, the departments immediately rose to protest against the new revolution of Paris. Before a counter-despatch could be sent down into the provinces, to let them know that the former order of things was restored, the national guards of all the great towns were up and out, with the cry "to arms!" and it was resolved to march upon Paris. It was not only in the towns within a day's journey of the capital that the movement was spontaneously made. In the furthest parts of the country, from the cities of Avignon, Marseilles, Nismes, and all the south of France, the national guards were already on their way towards the capital, before the information that declared the more satisfactory result of the day could be made public. It is more than probable, then, that, should a desperate faction ever seize upon the power, or even should a close conflict of parties further endanger the safety of the country and its tottering welfare, that the provinces would again take up arms against Paris, and that a civil war would be the result.

This is rather a suggestion hazarded, than a prediction made, as to the future fate of the French republic. Whatever that future may be, an uneasy submission on the part of a great anti-republican majority to the active agency of a small republican minority – but, at the same time, a desire of maintaining a government, whatever it may be, if supportable, for tranquillity's sake; a feeling of humiliation and degradation in this utter submission to the will of Paris throughout the country – but, at the same time, an apparent growing determination eventually to resist that will, should it at last prove intolerable – such is the present state of Republican France.

COLONISATION

Journal of an Expedition into the Interior of Tropical Australia, &c. By Lieut. – Colonel Sir T. Mitchell, Surveyor-General, &c. 1 vol. London: Longmans.

Australia is the greatest accession to substantial power ever made by England. It is the gift of a Continent, unstained by war, usurpation, or the sufferings of a people. But even this is but a narrow view of its value. It is the addition of a territory, almost boundless, to the possessions of mankind; a location for a new family of man, capable of supporting a population equal to that of Europe; or probably, from its command of the ocean, and from the improved systems, not merely of commercial communication, but of agriculture itself, capable of supplying the wants of double the population of Europe. It is, in fact, the virtual future addition of three hundred millions of human beings, who otherwise would not have existed. And besides all this, and perhaps of a higher order than all, is the transfer of English civilisation, laws, habits, industrial activity, and national freedom, to the richest, but the most abject countries of the globe; an imperial England at the Antipodes, securing, invigorating, and crowning all its benefits by its religion.

Within the last fifty years, the population of the British islands has nearly tripled; it is increasing in England alone at the rate of a thousand a day. In every kingdom of the Continent it is increasing in an immense ratio. The population is becoming too great for the means of existence. Every trade is overworked, every profession is overstocked, every expedient for a livelihood threatens to be exhausted under this vast and perpetual influx of life; and the question of questions is, How is this burthen to be lightened?

There can be but one answer, – Emigration. For the last century, common sense, urged by common necessity, directed the stream of this emigration to the great outlying regions of the western world. North America was the chief recipient. Since the conquest of Canada, annual thousands had directed their emigration to the British possessions: the conquest of the Cape has drawn a large body of settlers to its fine climate; but Australia remained, and remains for the grand future field of British emigration.

The subject has again come before the British public with additional interest. The Irish famine, the British financial difficulties, and the palpable hazard of leaving a vast pauperism to grow up in ignorance, have absolutely compelled an effort to relieve the country. A motion has just been made in Parliament by Lord Ashley, giving the most startling details of the infant population; and demanding the means of sending at least its orphan portion to some of those colonial possessions, where they may be trained to habits of industry, and have at least a chance of an honest existence. We shall give a few of these details, and they are of the very first importance to humanity. On the 6th of June Lord Ashley brought in a resolution, "That it is expedient that means be annually provided for the voluntary emigration, to some one of her Majesty's colonies, of a certain number of young persons of both sexes, who have been educated in the schools, ordinarily called 'ragged schools,' in and about the metropolis."

In the speech preparatory to this resolution, a variety of statements were made, obtained from the clergy and laity of London. It was ascertained that the number of children, either deserted by their parents, or sent out by their parents to beg and steal, could not be less than 30,000 in the metropolis alone. Their habits were filthy, wretched, and depraved. Their places of living by day were the streets, and by night every conceivable haunt of misery and sin. They had no alternative but to starve, or to grow up into professional thieves, perhaps murderers. Of the general population, the police reports stated, that in 1847 there had been taken into custody 62,181 individuals of both sexes and all ages. Of these, 20,702 were females, and 47,479 males. Of the whole, 15,693 were under twenty years of age, 3,682 between fifteen and ten, and 362 under ten. Of the whole, 22,075 could neither read nor write, and 35,227 could read only, or read and write imperfectly.

The average attendance last year in the "ragged schools" was 4000. Of these 400 had been in prison, 600 lived by begging, 178 were the children of convicts, and 800 had lost one or both their parents, and of course were living by their own contrivances. Out of the 62,000, there were not less than 28,113 who had no trade, or occupation, or honest livelihood whatever!

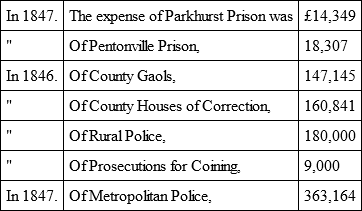

The statement then proceeded to consider the expense to which the nation was put to keep down crime. It will perhaps surprise those readers who object to the expenses of emigration.

The whole but a few items, yet amounting to a million sterling annually. In this we observe the Millbank Penitentiary, an immense establishment, Newgate, the Compter, and the various places of detention in the city, are not included; and there is no notice of the expenses of building, which in the instance of the Penitentiary alone amounted to a million.

Yet, to dry up the source of this tremendous evil, Lord Ashley asks only an expenditure of £100,000 annually, to transform 30,000 growing thieves into honest men, idlers into cultivators of the soil, beggars into possessors of property, which the generality of settlers become, on an average of seven years.

There can be no rational denial of the benefit, and even of the necessity, of rescuing those unfortunate creatures from a career which, beginning in vice and misery, must go on in public mischief, and end in individual ruin. Lord Ashley's suggestion is that the plan shall be first tried on the moderate scale of sending 500 boys, and 500 girls, chosen from the ragged schools of London, under proper superintendents, to the most fitting of the colonies; by which we understand Australia. The plan may then be extended to the other parts of the kingdom, to Scotland and Ireland. He concluded by placing his motion in the hands of government, who, through the Home Secretary, promised to give it all consideration.

It is certainly lamentable that such statements are to be made; and we have little doubt that the foreign journalist will exult in this evidence of what they call "the depravity of England." But, it is to be remembered that London has a population of nearly two millions – that all the idleness, vice, and beggary of an island of twenty millions are constantly pouring into it – that foreign vice, idleness, and beggary contribute their share, and that what is abhorred and corrected in England, is overlooked, and even cherished abroad. It is also to be remembered, that there is a continual temptation to plunder in the exposed wealth of the metropolis, and a continual temptation to mendicancy in the proverbial humanity of the people.

Still, crime must be punished wherever it exists, and vice must be reformed wherever man has the means; and, therefore, we shall exult in the success of any judicious plan of emigration.

It happens, at this moment, that there is an extraordinary demand for emigration; that every letter from Australia calls for a supply of human life, and especially for an emigration of females, – the proportion of males to females in some of the settlements being 9 to 1, while the number of females predominates, by the last census in England.

There is a daily demand for additional labourers, artificers, and household servants, and with offers of wages which in England neither labourer nor artisan could hope to obtain. Thousands are now offered employment, comfort, and prospective wealth in Australia, who must burthen the workhouse at home. The advantages are so evident, the necessity is so strong, and the opportunity is so prompt and perfect, that they must result in a national plan of constant emigration, until Australia can contain no more – an event which may not happen for a thousand years.

It happens, also, by a striking coincidence, that Australian discovery has just assumed new vigour; and that instead of the barrenness and deformity which were generally supposed to form the principal characteristics of this vast territory, immense tracts have been brought to European knowledge for the first time, exhibiting remarkable fertility, and even the most unexpected and singular beauty. We now give a sketch of the journey in which those discoveries were made.

To explore the interior of this great country has been the object of successive expeditions for the last five-and-twenty years. But such was the want of system or the want of means, that nothing was done, except to increase the tales of wonder regarding the middle regions of Australia. The theorists were completely divided; one party insisting on the existence of a mediterranean or mighty lake in the central region, because there was a tendency in some of the small rivers of the coast to flow inward. Others, with quite as much plausibility, laughed at the idea; and, from having felt a hot wind occasionally blowing from the west, had no doubt that the central region was a total waste, a desert of fiery sand, an Australian Sahara! while both parties seem to have been equally erroneous, so far as any actual discovery has been made.

But it seems equally extraordinary, that even the only two expeditions which within our time have added largely to our knowledge, alike should have neglected the most obvious and almost the only useful means of discovery. The especial object of exploration must be, to ascertain the existence of considerable rivers pouring into the sea, because it is only thus that the government can effectively form settlements. The especial difficulty of the explorers is, to find provisions, or carry the means of subsistence along with them. Both difficulties would be obviated by the steam-boat, and by nothing else. The natural process, therefore, would be, to embark the expedition in a well appointed and well provisioned steamer; to anchor it at the necessary distance from the coast, which in general has deep and sheltered water, within the great rocky ridge; and then send out the explorers for fifty or a hundred miles north and south, making the steamer the headquarters. Thus they might ascertain every feature of the coast, inch by inch, be secure of subsistence, and be free from native hostility.

Yet all the expeditions have been overland, generally with the most imminent hazard of being starved, and occasionally losing some of their number by attacks from the natives. Thus also the present expedition of the surveyor succeeded but in part, though it had the merit of discovering that the reports of Australian barrenness belonged but to narrow tracts, while the general character of the country towards the north was of striking fertility. The purpose of Sir T. Mitchell's late expedition was, to ascertain the probability of a route from Sydney to the Gulf of Carpentaria. But as this route was to be made dependent on a presumed river flowing into the gulf, the actual object was to reach the head of that river – an object which could have been more effectually attained by tracing it upward from the gulf; and, in consequence of not so tracing it, the expedition ultimately failed.

To establish an easy connexion between the colony of New South Wales and the traffic of the Indian Ocean had long been a matter of great interest. Torres Strait, the only channel to the north, is a remarkably dangerous navigation; while, by forming an overland communication directly with the Gulf of Carpentaria to the west of the strait, the commerce would find an open sea. A trade in horses had also commenced with India, which was impeded by the hazards of the strait. There had also been a steam communication with England by Singapore, and there was a hope that this line might be connected with a line from the gulf.

The idea of tracing a river towards the north was a conjecture of several years' standing, in some degree founded on the natural probability that an immense indentation of the land could not but exhibit some outlet for the course of a considerable fall of waters, and also that there had been a report by a Bushman, of having followed its course to the sea.

After some difficulties with the governor, which were obviated by a vote of the Colonial Legislature of £2000 for the expenses of the expedition, it set out from Paramatta on the 17th of November 1845. The expedition consisted of Sir Thomas Mitchell; E. B. Kennedy, Esq., assistant-surveyor; William Stephenson, Esq., surgeon and naturalist; twenty-three convicts, who volunteered for the sake of a free pardon, which was to be their only payment; and three freemen. They had a numerous list of baggage conveyances, &c. &c.; eight drays, drawn by eighty bullocks; two boats, thirteen horses, four private horses, three light carts, and provisions for a year, including two hundred and fifty sheep, which travelled along with them, constituting a chief part of their animal food. They had also gelatine and pork. The surveyor-general preferred light carts, and horses in place of bullocks; but it was suggested that the strong drays were necessary, and that bullocks were more enduring than horses – the latter an opinion soon found to be erroneous. It is rather singular, that either opinion should not have been settled fifty years ago.

Some natural and well-expressed reflections arise, in the course of this volume, on the lonely life of the settler. Its despondency, and its inutility to advance his moral nature, are in some measure attributed to the absence of the "gentler sex."

"At this sheep station," says Sir Thomas, "I met with an individual who had seen better days, and had lost his property amid the wreck of colonial bankruptcies; a 'tee-totaller,' with Pope's 'Essay on Man' for his consolation, in a bark hut. This man spoke of the depravity of shepherd life as excessive… The pastoral life, so favourable to the enjoyment of nature, has always been a favourite with the poets. But here it appears to be the antipodes of all poetry and propriety, simply because man's better half is wanting. Under this unfavourable aspect the white man comes before the aboriginal. Were they intruders, accompanied with wives and children, they would not be half so unwelcome. In this, too, consists one of the most striking differences between settling and squatting. Indeed, if it were an object to uncivilise the human race, I know of no method more likely to effect it, than to isolate a man from the gentler sex and children. Remove afar off all courts of justice and means of redress of grievances, all churches and schools, all shops where he can make use of money, and then place him in close contact with savages. 'What better off am I than a black native!' was the exclamation of a shepherd to me."