полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 64, No. 393, July 1848

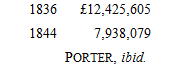

Such have been the effects of free-trade principles on the comparative prosperity of British and foreign shipping, on the showing of the Free-traders themselves, and according to the figures which their great statistician, Mr Porter, has prepared and published at the Board of Trade. We were unwilling to mix up a great national question, such as the repeal of the Navigation Laws, with any subordinate examination as to the accuracy or inaccuracy of the view of our maritime affairs which these figures exhibit. Such is the strength of the case, that it will admit of almost any concession; and the opponents of their repeal have no occasion to go farther than to the statistics of their adversaries for the most decisive refutation of their principles. But there are two observations on the tables published by the Board of Trade, so important that they cannot be passed over in silence. The first is, that in 1834, when Mr Poulett Thomson was president of the Board of Trade, a regulation was made by the Board as to the measurement of vessels, which had the effect of adding a fifth to the apparent tonnage of all British vessels, subsequent to that date. This change was clearly proved by the witnesses examined before the Commons' committee; but though Mr Porter, in his last edition of the Progress of the Nation, mentions the change, (p. 368,) he makes no allusion to it in comparing the amount of British and foreign tonnage since 1834. Of course a fifth must be deducted from British tonnage, as compared with foreign, since that time; and what overwhelming force does this give to the facts, already strong, in regard to the effect of the reciprocity system on our maritime interests!

The second is, that the tonnage with countries near Great Britain, such as France, Belgium, and Holland, includes steam vessels carrying passengers, and their repeated voyages. In this way a boat, measuring 148 tons, and carrying passengers chiefly, comes to figure in the returns for 24,000 tons! It is evident that this important circumstance deprives the returns of such near states of all value in the estimate of the comparative amount of tonnage engaged in the trade with different countries. That with France will appear greatest in spring 1848, in consequence of the number of large vessels then employed in bringing back English residents expelled by, or terrified at, the Revolution – though that circumstance was putting a stop to nearly all the commercial intercourse between the two countries. As steam navigation has so immensely increased since 1834, when the changes in the measurement was introduced – and Great Britain, from its store of coal and iron, enjoys more of that traffic than all Europe put together – this is another circumstance which militates against the returns as exhibiting a fair view of our trade, compared with that of foreign nations, especially with near countries, and fully justifies Mr Porter's admission, when examined before the Lords' committee, that "considerable fallacy is to be found in the returns." Unfortunately for the Free-traders, however, who had the preparation of them in their hands, these fallacies all point one way – viz. to augment the apparent advantages of free trade in shipping.

Such as free-trade principles are, they are evidently not likely to remain, if these islands are excepted, long in the ascendant either in the Old or the New World. The American tariff shows us how little we have to expect from Transatlantic favour to our manufactures: the savage expulsion of English labourers from France, how far the principles of "Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity," are likely to be acted upon by our enthusiastic and democratic neighbours on the Continent of Europe. It is clear from the communist and socialist principles now in the ascendant, both at Paris, Berlin, and Vienna, that the interests of labour will above all things be considered by their governments in future times, and that the most rigorous measures, in the form of fiscal regulations, if not absolute prohibition, may shortly be expected in France, Italy, and Germany, against manufactures of any sort which interfere, or seem to interfere, with the interests of the dominant multitude of operatives. Why does our government adhere so strongly, in the face of the clearest evidence of their ruinous tendency, to the present system of free trade and a fettered currency? Because it works well for the great capitalists, who desire to have money dear, and the great manufacturers, who wish to have labour cheap, and because a majority of the House of Commons has been placed by the Reform Bill under their influence. Give the operatives the majority, and the opposite interest will instantly prevail. A successful Chartist revolt would at once send the whole free trade and fettered currency measures by the board in three months. In truth, it is the disasters they have produced which has revived Chartism, and rendered it so menacing in the land. We should like to see how long a legislature, elected by universal suffrage, would allow Spitalfields and Macclesfield to be pauperised by Lyons silks, and Manchester invaded by Rouen cottons, and the shipwrights of Hull and Sunderland to be ruined by Baltic shipbuilders. As the operative classes have obtained the ascendency in the principal Continental states, a similar jealousy of foreign interference with industry may with certainty be looked for in Continental Europe. Can any thing be more insane, therefore, than to persist in a policy fraught, as every thing around us demonstrates, with such ruinous social injury to ourselves, and which the progress of political change on the Continent renders incapable of producing the ultimate benefits, in exchange for those evils which their authors hold out as the inducing causes of the measures which have produced them?

While the political changes which have recently occurred on the Continent of Europe have rendered any reciprocity of advantages utterly hopeless from the most violent adoption of free-trade principles, they have augmented in a proportional degree the dangers to this country of foreign aggression, and the risk to be apprehended from any diminution of our naval resources. The days have gone by when the dream of a free-trade millenium, in which a reciprocity of advantages is to extinguish all feelings of hostility, and war is to be looked back to as a relic of the pre-Adamite world, can with safety be indulged. It is rather too late to think of the termination of the angry passions of men, when Europe, in its length and breadth, is devastated alike by civil dissension and foreign warfare; when barricades have so recently been erected in all its chief capitals; when bloodshed is hourly expected in Paris and Berlin; when the Emperor of Austria has fled to Innspruck; when every station in London was, only a few days ago, occupied by armed battalions; and when a furious war, rousing the passions of whole races of men, is raging on the Mincio and the Elbe. Threatened by a raging fire in all the countries by which we are surrounded, uncertain whether we are not slumbering on the embers of a conflagration in our own, is this the time to relax in our warlike preparations, and, by crippling the nursery of our seamen, expose ourselves, without the means of resistance, to the assaults of hostile nations, envious of our fame, jealous of our manufactures, covetous of our wealth, desirous of our ruin?

While Western Europe is torn by revolutionary passions, and the seeds of a dreadful, because a popular and general war, are rapidly springing to maturity from the Seine to the Vistula, Russia is silently but unceasingly gathering up its giant strength, and the Czar has already 300,000 men, and 800 pieces of cannon, ready to take the field against the revolutionary enthusiasts of France and Germany. Sooner or later the conflict must arrive. It is not unlikely that either a second Napoleon will lead another crusade of the western nations across the Niemen, or a second Alexander will conduct the forces of the desert to the banks of the Seine. Whichever proves victorious, England has equal cause for apprehension. If the balance of power is subverted on Continental Europe, how is the independence of this country to be maintained? How are our manufactures or revenue to be supported, if one prevailing power has subjugated all the other states of Europe to its sway? It is hard to say whether, in such circumstances, we should have most to dread from French fraternity or Russian hostility. But how is the balance of power to be preserved in Europe amidst the wreck of its principal states? when Prussia is revolutionised, and has passed over to the other side; when Austria is shattered and broken in pieces, and Italy has fallen under the dominion of a faction, distinguished beyond any thing else by its relentless hatred of the aristocracy, and jealousy of the fabrics of England? What has Great Britain to rely on in such a crisis but the energy of its seamen and the might of its navy, which might at least enable it to preserve its connexion with its own colonies, and maintain, as during the Continental blockade, its commerce with Transatlantic nations? And yet this is the moment which our rulers have selected for destroying the Navigation Laws, so long the bulwark of our mercantile marine, and permitting all the world to make those inroads on our shipping, which have already been partially effected by the nations with whom we have concluded reciprocity treaties!

The defence of Great Britain must always mainly rest on our navy, and our navy is almost entirely dependent on the maintenance of our colonies. It is in the trade with the colonies that we can alone look for the means of resisting the general coalition of the European powers, which is certain, sooner or later, to arise against our maritime superiority, and the advent of which the spread of democratic principles, and the sway of operative jealousy on the Continent, is so evidently calculated to accelerate. But how are our colonies to be preserved, even for a few years, if free-trade severs the strong bond of interest which has hitherto attached them to the mother country, and the repeal of the Navigation Laws accustoms them to look to foreigners for the means of conducting their mercantile transactions? Charged with the defence of a colonial empire which encircles the earth, and has brought such countless treasures and boundless strength to the parent state, Great Britain at land is only a fourth-rate power, at least for Continental strife. At Waterloo, even, she could only array forty-five thousand men to contend with the conqueror of Europe for her existence. It is in our ships we must look for the means of maintaining our commerce, and asserting our independence against manufacturing jealousy, national rivalry, and foreign aggression. Is our navy, then, to be surrendered to the ceaseless encroachments of foreigners, in order to effect a saving of a few millions a-year on freights, reft from our own people, and sapping the foundations of our national independence?

How can human wisdom or foresight, the energy of the Anglo-Saxons, or the courage of the Normans, maintain, for any length of time, our independence in the perilous position into which free-trade policy has, during the short period it has been in operation, brought us? The repeal of the Corn Laws has already brought an importation of eight or ten millions of foreign quarters annually upon our people – a full sixth of the national subsistence, and which will soon become indispensable to their existence. A simple non-intercourse act will alone enable Russia or America, without firing a shot, to compel us to lower the flag of Blake and Nelson. Stern famine will "guard the solitary coast," and famished multitudes demand national submission as the price of life. The repeal of the Navigation Laws will ere long bring the foreign seamen engaged in carrying on our trade to a superiority over our own, as has already taken place in so woful a manner with the Baltic powers. Hostile fleets will moor their ships of the line across our harbours, and throw back our starving multitudes on their own island for food, and their own market for employment. What will then avail our manufacturers and our fabrics, – the forges of Birmingham, the power-looms of Manchester, the iron-works of Lanarkshire, – if the enemies' squadrons blockade the Thames, the Mersey, and the Clyde, and famished millions are deprived alike of food and employment, by the suicidal policy of preceding rulers? Our present strength will then be the measure of our weakness; our vast population, as in a beleaguered town, the useless multitude which must be fed, and cannot fight, – our wealth, the glittering prize which will attract the rapacity of the spoiler. With indignant feelings, but caustic truth, our people will then curse the infatuated policy which abandoned the national defences, and handed them over, bound hand and foot, to the enemy, only the more the object of rapacity because such boundless wealth had accumulated in a few hands amongst them. Then will be seen, that with our own hands, as into the ancient city, we have admitted the enemies' bands; we have drawn the horse pregnant with armed men through our ramparts, and our weeping and dispersed descendants will exclaim with the Trojans of old —

"Fuimus Troës, fuit Ilium, et ingens

Gloria Teucrorum."

1

We suspect this custom may be traced in the Scythian legends of Herodotus. See his 4th book, chapters v., vi., and x.

2

See Erskine's Institutes, B. iii. tit. 8, §§ 21-25.

3

Saddle-blanket made of buffalo-calf skin.

4

The French Canadians are called wah-keitcha– "bad medicine" – by the Indians, who account them treacherous and vindictive, and at the same time less daring than the American hunters.

5

We fully agree with our correspondent as to the danger of Whiggery in our councils, but are so far reconciled to the Whigs being in office at the present crisis, by the knowledge that, had they been in opposition, they would, to a certain extent, have fraternised with French Republicans and English Chartists. Who could doubt that such would have been the conduct of the men who headed physical force processions, and hounded on window-breaking vagabonds in the Reform riots of 1830? What amount of profligate partisanship might not be expected from the men who, when thirsting for office, solemnly denounced as unconstitutional and unjust the course pursued by a conservative government towards O'Connell, which identical course they now, when in power, adopt towards Mitchell, a much less dangerous criminal?

6

Burke's Reflections on the French Revolution.

7

Gospodin Slujivui. Gospodin is equivalent to the French Monsieur or Seigneur, and Slujivui means literally one who has served in the army.

8

Wealth of Nations, iv. c. 2.

9

Times, June 9, 1848.

10

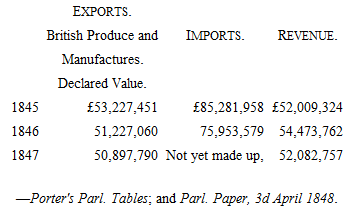

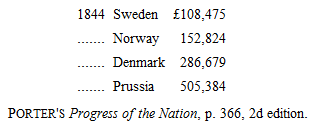

Exports from Great Britain – to

11

Exports to United States of America: —

12