полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 60, No. 373, November 1846

It is a well-known English foible to think nothing good unless the price be high. This was strikingly exemplified in Afghanistan, where every thing was done virtually to lower the value of money. The labourers employed by our engineer officers were paid at so high a rate that there was a general strike, and agriculture was brought to a stand-still. The king's gardens were to be put in order, but not a workman was to be had except for English pay. The treasury could not afford to satisfy such exorbitant demands, and the people were made to work, receiving the regular wages of the country. Clamour and complaint were the consequence, and the English authorities informed Mullah Shakur, that if he did not satisfy the grumblers, they would pay them for the Shah, thus constituting him their debtor. Shuja's jealousy increased, and he showed his irritation by various petty attempts at annoyance. Discontent was rife in Afghanistan, even when the general impression amongst the English officers there, was, that the country was quiet and the people satisfied. Colonel Herring was murdered near Ghazni; a chief named Sayad Hassim rebelled, but was subdued, and his fort taken, by Colonel Orchard and the gallant Major Macgregor.

It was at this critical period that news came to Kabul of Dost Mohammed's escape from Bokhara. The Shah of Persia had rebuked the Bokhara ambassador for his master's harsh treatment of the Amir, whereupon the latter was allowed more liberty, of which he took advantage to escape. On the road his horse knocked up, but he luckily fell in with a caravan, and obtained a place in a camel-basket. The caravan was searched by the emissaries of the King of Bokhara, but the Amir had coloured his white beard with ink, and thus avoided detection. He was received with open arms by the Mir of Shahar Sabz and the Vali of Khulam, and held counsel with those two chiefs and some other adherents as to the course he should adopt. It was resolved to make an attempt to recover Kabul, and measures were taken to collect money, men, and horses. The moment appeared favourable for the enterprise; the Afghan chiefs and people were discontented, and there were disturbances in Kohistan. Sir William MacNaghten knew not whom to trust; and a vast number of arrests were made on suspicion, some without the slightest cause, which increased the disaffection and want of confidence. On the 30th of August hostilities commenced with an attack by Afzal Khan on the British post at Bajgah. It was repulsed, and on the 18th of September the Amir and the Vali of Khulam were routed by Colonel Dennie. Dost Mohammed fled to Kohistan, many of whose chief inhabitants rallied round his standard, until he found himself at the head of five thousand men. He might have augmented this number, but for the exertions of Sir A. Burnes and Mohan Lal, who sent agents into the revolted country with money to buy up the inhabitants. This became known amongst the Amir's followers, and rendered him distrustful of them; for he feared they would be unable to withstand the temptations held out, and would betray him, in hopes of a large reward. On the 2d of November occurred a skirmish between the Amir's forces and the troops under General Sale and Shah Zadah, in which the 2d cavalry were routed, and several English officers killed, or severely wounded. Notwithstanding this slight advantage, and a retrograde movement effected the same night by the united British and Afghan division, the Amir felt himself so insecure, fearing even assassination at the hand of the Kohistanis, that, on the evening of the 30th November, he gave himself up to Sir William MacNaghten at Kabul. He was delighted with the kind and generous reception he met, and wrote to Afzal Khan and his other sons to join him. After a few days, the necessary arrangements being completed, he was sent to India.

The Amir a prisoner, the chief apparent obstacle to the tranquillity of Afghanistan was removed, and it was not unreasonable to suppose that Shah Shuja would thenceforward sit undisturbed upon the throne of his ancestors. Unfortunately such anticipations were erroneous. Had Dost Mohammed remained at large, any harm he could have done would have been inferior to that occasioned by the injudicious measures of the British agents. These measures, as Mohan Lal asserts, with, we fear, too much truth, were the very worst that could be devised for the attainment of the ends proposed. The Afghan character was misunderstood, Afghan customs and institutions were interfered with, and Afghan prejudices shocked. Certain things there were, which it would have been good policy to wink at, or appear ignorant of. The contrary course was adopted. On the field of Parvan, where the combat of the 2d November took place, a bag of letters was found, compromising a large number of chiefs and influential Kabulis. The Amir having surrendered, and as it was not intended to punish these persons, the wisest plan would have been to suppress the letters entirely; but this was not done, and the disclosure caused a vast deal of mistrust on the part of the suspected chiefs towards the English. It also gave a stimulus to a practice then very prevalent in Kabul, that of forging letters from persons of note, with a view to compromise the supposed writers, and to procure for the forgers money and English friendship. Much mischief was done by these letters, some of which were fabricated by Afghans enjoying the favour and confidency of Sir A. Burnes and Sir W. MacNaghten.

On the repeated solicitations of the English, the Vazir Mulla Shakur was dismissed. His successor, Nizam-ul-Daulah, was almost forced upon the Shah, whose power was thus rendered contemptible in the eyes of the Afghans. The new minister took his orders rather from the British agents than from his nominal master – going every day to the former to report what he had done, caring nothing for the good or bad opinion of the nation, or for the will of the Shah, whose mandates he openly disobeyed. Having committed an oppressive act, by depriving a Sayad of his land, Shuja repeatedly enjoined him to restore the property to its rightful owner. He paid no attention to these injunctions; and at last the Shah told the suppliant, when he again came to him for redress, "that he had no power over the Vazir, and therefore that the Sayad should curse him, and not trouble the Shah any more, because he was no more a king but a slave." By bribes to the newswriters of the envoy and Sir A. Burnes, Nizam-ul-Daulah endeavoured to keep his misdeeds from the ears of those officers. Nevertheless, they became known to them through Mohan Lal and others; but Sir A. Burnes "felt himself in an awkward position, and considered it impossible to cause the dismissal of one whose nomination he had with great pains so recently recommended."

A reform in the military department, recommended by Sir A. Burnes, caused immense bitterness and ill-blood amongst the chiefs, whose retinues were compulsorily diminished, the men who were to be retained, and those who were to be dismissed, being selected by a British officer. This was looked upon as an outrageous insult and grievous humiliation. The reduction was effected, also, in a harsh and arbitary manner, without consideration for the pride of the chiefs and warriors, by whom all these offences were treasured up, to be one day bloodily revenged. Other innovations speedily followed and increased their discontent; until at last they were reduced to so deplorable a position that they waited in a body upon Shah Shuja to complain of it. The Shah imprudently replied, that he was king by title only, not by power, and that the chiefs were cowards, and could do nothing. These words Mohan Lal believes were not spoken to stimulate the chiefs to open rebellion, but merely to induce them to such acts as might convince the English of the bad policy of their reforms and other measures. But the Shah had miscalculated the effect of his dangerous hint. After the interview with him, at the end of September 1841, the chiefs assembled, and sealed an engagement, written on the leaves of the Koran, binding themselves to rebel against the existing government, as the sole way to annihilate British influence in Kabul. Mohan Lal was informed of this plot, and reported it to Sir A. Burnes, who attached little importance to it, and refused to permit the seizure of the Koran, whence the names of the conspirators might have been learned. It has been frequently stated, that neither Burnes nor MacNaghten had timely information of the discontent and conspiracy of the chiefs. Mohan Lal affirms the contrary, and supports his assertion by extracts from letters written by those gentlemen. Pride of power, he says, and an unfortunate spirit of rivalry, prevented them from taking the necessary measures to meet the outbreak. Sir A. Burnes thought that to be on the alert would show timidity, whilst carelessness of the alarming reports then afloat would prove intrepidity, and produce favourable results. But it was not the moment for such speculations. A circular letter was secretly sent round to all the Durrani and Persian chiefs in Kabul and the suburbs, falsely stating that a plan was on foot to seize them and send them to India, whither Sir W. MacNaghten was about to proceed as governor of Bombay. The authors of this atrocious forgery were afterwards discovered. They were three Afghans of bad character and considerable cunning, who had been employed by the Vazir, by the envoy, and by Sir A. Burnes. Their object was to produce a revolt, in which they might make themselves conspicuous as friends of the English, and so obtain reward and distinction. They had been wont to derive advantage from revolutions and outbreaks, and were eager for another opportunity of making money. Their selfish and abominable device was the spark to the train. It caused a prompt explosion. The chiefs again assembled, resolved upon instant action, and fixed upon its plan. It was decided to begin by an attack upon the houses of Sir A. Burnes and the other English officers resident in the city. For fear of discovery, not a moment was to be lost. The following day, the 2d of November, was to witness the outbreak.

And now, at the eleventh hour, fresh intimations of the approaching danger were conveyed to those whom it threatened. Two persons informed Sir A. Burnes of it; and one of the conspirators more than hinted it to Mohan Lal, who had boasted to him that the Ghilzais were pacified by Major Macgregor, and that Sir Robert Sale was on his victorious march to Jellalabad. The conspirator laughed. "To-morrow morning," he said, "the very door you now sit at will be in flames of fire; and yet still you pride yourselves in saying that you are safe!"

"I told all this," says Mohan Lal, "to Sir Alexander Burnes, whose reply was, that we must not let the people suppose we were frightened, and that he will see what he can do in the cantonment, whither he started immediately. Whilst I was talking with Sir A. Burnes, an anonymous note reached him in Persian, confirming what he had heard from me and from other sources, on which he said, 'The time is arrived that we must leave this country.'" The time for that was already past.

The disastrous occurrences in Afghanistan, on and subsequently to the 2d of November 1841, are so recent, so well-known, and have been so much written about, that any thing beyond a passing reference to them is here unnecessary. Mohan Lal's account of the deaths of Sir A. Burnes, Charles Burnes, Sir W. MacNaghten, and Shah Shuja, is interesting, as are also some details of his own escapes and adventures during the insurrection. From the roof of his house he witnessed the attack upon that of Sir A. Burnes, and the death of Lieutenant H. Burnes, who slew six Afghans before he himself was cut to pieces. Sir Alexander was murdered without resistance, having previously tied his cravat over his eyes, in order not to see the blows that put an end to his existence. Mohan Lal himself narrowly escaped death at the hands of the man who subsequently murdered Shah Shuja; but he was rescued by an Afghan friend, and concealed in a harem. Afterwards, whilst prisoner to Akhbar Khan, he did good service in sending information to the English generals and political agents, and finally in negotiating the release of the Kabul captives. For all these matters we refer our readers to the closing chapters of his book, and return to Dost Mohammed.

On his arrival at Calcutta, the Amir was treated by Lord Auckland with great attention and respect, an income of three lakhs of rupees was allotted to him, and he was taken to see the curiosities of the city, the naval and military stores, &c. All these things greatly struck him, and he was heard to say, that had he known the extraordinary power and resources of the English, he would never have opposed them. After a while, his health sufferred from the Calcutta climate; he became greatly alarmed about himself, and begged to be allowed to join his family at Loodianah. He was sent to the upper provinces, and afterwards to the hills, where the temperature was cool and somewhat similar to that of his own country. During the Kabul insurrection he managed to keep up a communication with his son Akhbar, whom he strongly advised to destroy the English by every means in his power.

When the British forces re-entered Afghanistan to punish its inhabitants for the Kabul massacres, Prince Fatah Jang, son of the murdered Shah Shuja, was placed upon the throne. But when he found that his European supporters, after accomplishing the work of chastisement, were about to evacuate the country with a precipitation which, it has been said, "resembled almost as much the retreat of an army defeated as the march of a body of conquerors,"46 he hastened to abdicate his short-lived authority. He was too good a judge of the chances, to await the departure of the British and the arrival of Akhbar Khan, and preferred taking off his crown himself to having it taken off by somebody else, with his head in it. His brother, Prince Shahpur, a mere boy, was then seated upon the throne, and left at the mercy of his enemies. His reign was very brief. As the English marched from Kabul, Akhbar Khan approached it, and the son of Shuja had to run away, with loss of property and risk of life. "By such a precipitate withdrawal from Afghanistan," says Mohan Lal, "we did not show an honourable sentiment of courage, but we disgracefully placed many friendly chiefs in a serious dilemma. There were certain chiefs whom we detached from Akhbar Khan, pledging our honour and word to reward and protect them; and I could hardly show my face to them at the time of our departure, when they came full of tears, saying, that 'we deceived and punished our friends, causing them to stand against their own countrymen, and then leaving them in the mouths of lions.' As soon as Mohammed Akhbar occupied Kabul, he tortured, imprisoned, extorted money from, and disgraced, all those who had taken our side. I shall consider it indeed a great miracle and a divine favour, if hereafter any trust ever be placed in the word and promise of the authorities of the British government throughout Afghanistan and Turkistan."

When it at last became evident that the feeble and talentless Sadozais were unable to hold the reins of power in Afghanistan, or to contend, with any chance of success, against the energy and influence of the Barakzai chiefs, Dost Mohammed was released, and allowed to return to his own country. On his way he concluded a secret treaty of alliance with Sher Singh, the Maharajah of the Punjaub, and from Lahore was escorted by the Sikhs to the Khaibar pass, where Akhbar Khan and other Afghan chiefs received him. The Amir's exultation at again ascending his throne knew no bounds. Unschooled by adversity, he very soon recommenced his old system of extortion, and made himself so unpopular, that he was once fired at, but escaped. He now enjoys his authority and the superiority of his family, fearless of invasion from West or East.

Although Akhbar Khan, of all the Amir's sons, has the greatest influence in Afghanistan, and renown out of it, his elder brother, Afzal Khan, is, we are informed, greatly his superior in judgment and nobility of character. Mohan Lal predicts a general commotion in Kabul when Dost Mohammed dies. If any one of his brothers, the chiefs of Qandhar, or Sultan Mohammed Khan, the ex-chief of Peshavar, be then alive, he will attempt to seize Kabul, and many of the Afghan nobles, some even of the Amir's sons, will lend him their support against Akhbar Khan. The popular candidate, however, the favourite of the people, of the chiefs, and of his relations, the Barakzais, is Afzal Khan. Akhbar will be supported by his brothers – the sons, that is to say, of his own mother as well as of the Amir. Perhaps the whole territory of Kabul will be divided into small independent principalities, governed by the different sons of Dost Mohammed. At any rate, there can be little doubt that at his death wars and intrigues, plunderings and assassinations, will again distract the country. The crown that was won by the crimes of the father, will, in all probability, be shattered and pulled to pieces by the dissensions and rivalry of the children.

ON THE OPERATION OF THE ENGLISH POOR-LAWS

The time has arrived when the modes of administering the poor-law in England and Wales must undergo inquiry and revision. Twelve years have elapsed since the Poor-Law Amendment Act became the law of the land; and during the period many changes have been made. In many cases, the new arrangements of the Poor-Law Commissioners have been adopted without a murmur. In some cases, they have met with continued but fruitless opposition. In others, they have been resisted with success. During the whole period a war has raged, in which no two of the combatants have used the same weapons, or drawn them in the same cause. One has adduced particular cases of hardship, suffering, and death, as the results of the new system. Another has collected statistics, and referred to depauperised counties. And yet the same number of cases of hardship and suffering may have occurred before 1834, although unrecorded and unknown. Nor does it follow, because the official returns from agricultural counties may show a diminished number of paupers, or a diminished expenditure, that the residue have been able to earn their bread as independent labourers. No period appears to have been assigned when the results of the new system should be examined. Successive governments have kept aloof from fear, until an accident led to important disclosures, and an inquiry is now inevitable. The Poor-Law Commissioners have been invested with extraordinary and dangerous powers. They possess the united powers of Queen, Lords, and Commons. Their most imperfectly-considered resolutions have the force of an act of parliament, or rather, ten-fold more force – it being their duty, first, to ascertain what ought to be the law – then to make the law – then to enforce it – and then, after the elapse of time, to report upon its success or failure. It would be difficult for the wisest to exercise powers like these beneficially; and it is to be feared that abuses have crept in. And when we find that men, who have hitherto upheld the system, now demand inquiry in their place in parliament, and the ministers who were concerned in the establishment of the system, promising, either to withdraw opposition to the demand, or to amend the laws themselves so we may be assured that the topic at the present time, as regards the administration of Relief to the Poor in England and Wales, is Inquiry and Revision.

The subject matter of this article must be suggestive, rather than affirmative. Even at this time of day, it would be presumptuous to take up a commanding or decided position. The old system was rotten. The good it contained was choked up with weeds; the pruning-knife has been applied unsparingly; and it is to be feared that good wood has been cut away. New arrangements have been devised with practical shrewdness, to displace clearly recognised evils; but, with these practical improvements, certain economic theories have been speculatively, tried; and it is likely that evils have sprung up; so that those who proclaim so loudly that every part of the new arrangements is either naught or vicious, and those who affirm that the old methods were all good, are both remote from the truth, which, probably, lies somewhere between the two.

The subject being set apart for inquiry, the question arises – How can a subject which has so many phases be advantageously considered; to whom must we go for information; and to what matters should the attention be chiefly directed? It is to these questions this article will attempt to provide answers. To the first question – To whom must we go for information? – the answer is obvious. To all who are engaged in the administration of the law, and chiefly to those who have to do with those departments where evils may be supposed to exist. And, in order to answer the second, the subject must be divided into classes, and the mode of operation of the law in each must be sketched. The reader will then be able to see for himself, and judge whether the matters referred to are not those which most imperatively demand inquiry.

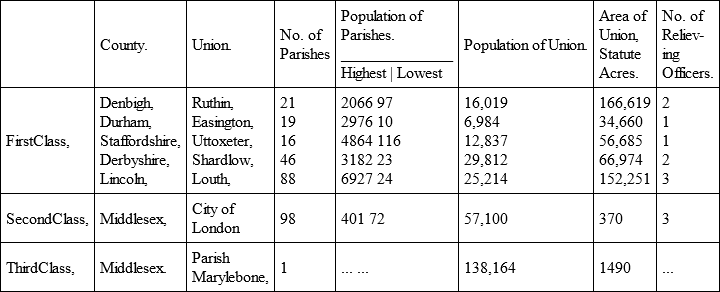

The several parishes, townships, chapelries, and hamlets of England and Wales, whether grouped into Unions or not, may be usefully distributed into three classes.

The First Class includes "parishes, townships, chapelries, and hamlets," grouped into Unions, in which the population bears a small proportion to the number of acres they comprise.

The Second Class includes small populous parishes, grouped into Unions, in which the population bears a large proportion to the number of statute acres they cover.

The Third Class consists of large single parishes, in which the population bears a large proportion to the number of acres.

The following diagram will explain this classification:

These divisions of territory may be regarded from different points of view. They may be seen through the media of statute-books, reports, returns, and statistics; or they may be actually surveyed. Each course has its peculiar dangers. The mind, occupied with matters of detail and routine occurrences, is apt to lose in comprehensiveness as much as it gains in minute exactness. To avoid this danger the mind must soar as the facts accumulate. It must regard them, sometimes from the height of one theory, and sometimes from the height of another. For the mind becomes tinged with the hue of whatever is frequently presented to it. Opinions even are hereditary. And every set of facts leads to a different conclusion, according to the texture of the minds they pass through. Refer to the facts connected with the condition of the poor, which have been proclaimed during the last few years; and then reflect to what contradictory opinions they have led. The man of strong benevolent feelings deduces one inference. The politico-economical theorist deduces another. And the man of practice and experience is as likely to be deluded as either. He sees destitution so frequently connected with imprudence, laziness, and crime, that he is apt to believe that the union is indissoluble. His mind has never embraced a general idea, or traced effects to causes, or distinguished them, the one from the other. And in this matter, where the causes and effects are so complicated, and entangled by their mutual reaction, he is likely to be at fault. Then the man of pure benevolence sees only the pain, and demands only the means of immediate relief. And the political economist tells us, "That the law which would enforce charity can fix no limits, either to the ever-increasing wants of a poverty which itself has created, or to the insatiable desires and demands of a population which itself hath corrupted and led astray."

In the First Class, the parishes are large, thinly populated, and situated generally in rural districts. In some cases, the Union includes a country town; the neighbouring parishes and hamlets being connected with it. The total number of parishes may be eighteen or twenty. In other cases, the Union consists of about twenty-five parishes, townships, hamlets, and chapelries. In some instances, the population of the parishes are collected into so many villages, which are distant from each other. In others, the entire surface of the country is sprinkled thinly with cottages. The communications are by high-roads, and muddy lanes, over high hills, and through bogs and marshes, and by bridle-roads and footpaths —