полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849

And the money profit which this attention to regularity will give, in addition to the satisfaction which attends it, is thus plainly set down: —

"Let us reduce the results of bad management to figures. Suppose you have three sets of beasts, of different ages, each containing 20 beasts – that is, 60 in all – and they get as many turnips as they can eat. Suppose that each of these beasts acquires only half a pound less live weight every day than they would under the most proper management, and this would incur a loss of 30 lbs. a-day of live weight, which, over 180 days of the fattening season, will make the loss amount to 5400 lbs. of live weight; or, according to the common rules of computation, 3240 lbs., or 231 stones, of dead weight at 6s. the stone, £69, 6s. – a sum equal to more than five times the wages received by the cattle-man. The question, then, resolves itself into this – whether it is not for your interest to save this sum annually, by making your cattle-man attend your cattle according to a regular plan, the form of which is in your own power to adopt and pursue?"

We must pass over the entire doctrine of prepared food, which has lately occupied so much attention, and has been so ably advocated by Mr Warner, Mr Marshall, Mr Thompson, and which, among others, has been so successfully practised by our friend Mr Hutton of Sowber Hill in Yorkshire. We only quote, by the way, a curious observation of Mr Robert Stephenson of Whitelaw in East-Lothian:

"'We shall conclude,' he says, 'by relating a singular fact' – and a remarkable one it is, and worth remembering – 'that sheep on turnips will consume nearly in proportion to cattle, weight for weight; that is, 10 sheep of 14 lbs. a-quarter, or 40 stones in all, will eat nearly the same quantity of turnips as an ox of 40 stones; but turn the ox to grass, and 6 sheep will be found to consume an equal quantity. This great difference may perhaps,' says Mr Stephenson, and I think truly, 'be accounted for by the practice of sheep cropping the grass much closer and oftener than cattle, and which, of course, prevents its growing so rapidly with them as with cattle.'"

The treatment of farm horses in winter is under the direction of the ploughman, whose duties are first described, after which the system of management and feeding of farm and saddle horses is discussed at a length of thirty pages.

Among other pieces of curious information which our author gives us is the nomenclature of the animals he treats of, at their various ages. This forms a much larger vocabulary than most people imagine, and comprises many words of which four-fifths of our population would be unable to tell the meaning.

Thus, of the sheep he informs us —

"A new-born sheep is called a lamb, and retains the name until weaned from its mother and able to support itself. The generic name is altered according to the sex and state of the animal; when a female it is a ewe-lamb, when a male tup-lamb, and this last is changed to hogg-lamb when it undergoes emasculation.

"After a lamb has been weaned, until the first fleece is shorn from its back, it receives the name of hogg, which is also modified according to the sex and state of the animal, a female being a ewe-hogg, a male a tup-hogg, and a castrated male a wether-hogg. After the first fleece has been shorn, another change is made in the nomenclature; the ewe-hogg then becomes a gimmer, the tup-hogg a shearling-tup, and the wether-hog a dinmont, and these names are retained until the fleece is shorn a second time.

"After the second shearing another change is effected in all these names; the gimmer is then a ewe if she is in lamb, but if not, a barren gimmer and if never put to the ram a eild gimmer. The shearling tup is then a 2-shear tup, and the dinmont is a wether, but more correctly a 2-shear wether.

"A ewe three times shorn is a twinter ewe, (two-winter ewe;) a tup is a 3-shear tup; and a wether still a wether, or more correctly a 3-shear wether– which is an uncommon name among Leicester sheep, as the castrated sheep of that breed are rarely kept to that age.

"A ewe four times shorn is a three winter ewe, or aged ewe; a tup, an aged tup, a name he retains ever after, whatever his age, but they are seldom kept beyond this age; and the wether is now a wether properly so called.

"A tup and ram are synonymous terms.

"A ewe that has borne a lamb, when it fails to be with lamb again is a tup-eill or barren ewe. After a ewe has ceased to give milk she is a yeld-ewe.

"A ewe when removed from the breeding flock is a draft ewe, whatever her age may be; gimmers put aside as unfit for breeding are draft gimmers, and the lambs, dinmonts or wethers, drafted out of the fat or young stock are sheddings, tails, or drafts.

"In England a somewhat different nomenclature prevails. Sheep bear the name of lamb until eight months old, after which they are ewe and wether teggs until once clipped. Gimmers are theares until they bear the first lamb, when they are ewes of 4-teeth, next year ewes of 6-teeth, and the year after full-mouthed ewes. Dinmonts are called shear hoggs until shorn of the fleece, when they are 2-shear wethers, and ever after are wethers."

The names of cattle are a little less complicated.

"The names given to cattle at their various ages are these: – A new-born animal of the ox-tribe is called a calf, a male being a bull-calf, a female a quey-calf, heifer-calf, or cow-calf; and a castrated male calf is a stot-calf, or simply a calf. Calf is applied to all young cattle until they attain one year old, when they are year-olds or yearlings—year-old bull, year-old quey or heifer, year-old stot. Stot, in some places, is a bull of any age.

"In another year they are 2-year old bull, 2-year-old quey or heifer, 2-year-old-stot or steer. In England females are stirks from calves to 2-year-old, and males steers; in Scotland both young male and females are stirks. The next year they are 3-year-old bull, in England 3-year-old female a heifer, in Scotland a 3-year-old quey, and a male is a 3-year-old stot or steer.

"When a quey bears a calf, it is a cow, both in Scotland and England. Next year the bulls are aged; the cows retain the name ever after, and the stots or steers are oxen, which they continue to be to any age. A cow or quey that has received the bull is served or bulled, and is then in calf, and in that state these are in England in-calvers. A cow that suffers abortion slips its calf. A cow that has either missed being in calf, or has slipped calf, is eill; and one that has gone dry of milk is a yeld-cow. A cow giving milk is a milk or milch-cow. When two calves are born at one birth, they are twins; if three, trins. A quey calf of twins of bull and quey calves, is a free martin, and never produces young, but exhibits no marks of a hybrid or mule.

"Cattle, black cattle, horned cattle, and neat cattle, are all generic names for the ox tribe, and the term beast is a synonyme.

"An ox without horns is dodded or humbled.

"A castrated bull is a segg. A quey-calf whose ovaries have been obliterated, to prevent her breeding, is a spayed heifer or quey."

Those of the horse are fewer, and more generally known —

"The names commonly given to the different states of the horse are these: – The new-born one is called a foal, the male being a colt foal, and the female a filly foal. After being weaned, the foals are called simply colt or filly, according to the sex, which the colt retains until broken in for work, when he is a horse or gelding which he retains all his life; and the filly is then changed into mare. When the colt is not castrated he is an entire colt; which name he retains until he serves mares, when he is a stallion or entire horse; when castrated he is a gelding; and it is in this state that he is chiefly worked. A mare, when served, is said to be covered by or stinted to a particular stallion; and after she has borne a foal she is a brood mare, until she ceases to bear, when she is a barren mare or eill mare; and when dry of milk, she is yeld. A mare, while big with young, is in foal. Old stallions are never castrated."

Those of the pig are as follows —

"When new-born, they are called sucking pigs, or simply pigs; and the male is a boar pig, the female sow pig. A castrated male, after it is weaned, is a shot or hog. Hog is the name mostly used by naturalists, and very frequently by writers on agriculture; but, as it sounds so like the name given to young sheep, (hogg,) I shall always use the terms pig and swine for the sake of distinction. The term hog is said to be derived from a Hebrew noun, signifying 'to have narrow eyes,' a feature quite characteristic of this species of animal. A spayed female is a cut sow pig. As long as both sorts of cut pigs are small and young, they are porkers or porklings. A female that has not been cut, and before it bears young, is an open sow; and an entire male, after being weaned, is always a boar or brawn. A cut boar is a brawner. A female that has taken the boar is said to be lined; when bearing young she is a brood sow; and when she has brought forth pigs she has littered or farrowed, and her family of pigs at one birth form a litter or farrow of pigs."

The diseases of cattle, horses, pigs, and poultry, are treated of – their management in disease, that is, as well as in health. And it is one of the merits of Mr Stephens that he has taken such pains in getting up his different subjects – that he seems as much at home in one department of his art as in another; and we follow him with equal confidence in his description of field operations, of servant-choosing and managing, of cattle-buying, tending, breeding, feeding, butchering, and even cooking and eating – for he is cunning in these last points also.

His great predecessor Tucker prided himself, in his "Five hundred points," in mixing up huswifry with husbandry: —

"In husbandry matters, where Pilcrow3 ye find,That verse appertaineth to Huswif'ry kind;So have ye more lessons, if there ye look well,Than huswif'ry book doth utter or tell."Following Tucker's example, our author scatters here and there throughout his book much useful information for the farmer's wife; and for her especial use, no doubt, he has drawn up his curious and interesting chapter on the treatment of fowls in winter. To show how minute his knowledge is upon this point, and how implicitly therefore he may be trusted in greater matters, we quote the following: —

"Every yellow-legged chicken should be used, whether male or female – their flesh never being so fine as the others." "Young fowls may either be roasted or boiled, the male making the best roasted, and the female the neatest boiled dish." "The criterion of a fat hen, when alive, is a plump breast, and the rump feeling thick, fat, and firm, on being handled laterally between the finger and thumb."

"Of a fat goose the mark is, plumpness of muscle over the breast, and thickness of rump when alive; and in addition, when dead and plucked, of a uniform covering of white fat under a fine skin on the breast." "Geese are always roasted in Britain, though a boiled goose is not an uncommon dish in Ireland; and their flesh is certainly much heightened in flavour by a stuffing of onions, and an accompaniment of apple sauce."

We suppose a boiled goose must be especially tasteless, as we once knew an old schoolmaster on the North Tyne, whose very stupid pupils were always christened boiled geese.

The threshing and winnowing of grain, which forms so important a part of the winter operations of a farm, naturally lead our author to describe and figure the different species of corn plants and their varieties, and to discuss their several nutritive values, the geographical range and distribution of each, and the special uses or qualities of the different varieties.

Widely spread and known for so many ages, the home or native country of our cereal plants is not only unknown, but some suppose the several species, like the varieties of the human race, to have all sprung from a common stock.

"It is a very remarkable circumstance, as observed by Dr Lindley, that the native country of wheat, oats, barley, and rye should be entirely unknown; for although oats and barley were found by Colonel Chesney, apparently wild, on the banks of the Euphrates, it is doubtful whether they were not the remains of cultivation. This has led to an opinion, on the part of some persons, that all our cereal plants are artificial productions, obtained accidentally, but retaining their habits, which have become fixed in the course of ages."

Whatever may be the original source of our known species of grain, and of their numerous varieties, it cannot be doubted that their existence, at the present time, is a great blessing to man. Of wheat there are upwards of a hundred and fifty known varieties, of barley upwards of thirty, and of oats about sixty. While the different species – wheat, barley, and oats – are each specially confined to large but limited regions of the earth's surface, the different varieties adapt themselves to the varied conditions of soil and climate which exist within the natural geographical region of each, and to the different uses for which each species is intended to be employed.

Thus the influence of variety upon the adaptation of the oat to the soil, climate, and wants of a given locality, is shown by the following observations: —

"The Siberian oat is cultivated in the poorer soils and higher districts, resists the force of the wind, and yields a grain well adapted for the support of farm-horses. The straw is fine and pliable, and makes an excellent dry fodder for cattle and horses, the saccharine matter in the joints being very sensible to the taste. It comes early to maturity, and hence its name."

The Tartarian oat, from the peculiarity of its form, and from its "possessing a beard, is of such a hardy nature as to thrive in soils and climates where the other grains cannot be raised. It is much cultivated in England, and not at all in Scotland. It is a coarse grain, more fit for horse-food than to make into meal. The grain is dark coloured and awny; the straw coarse, harsh, brittle, and rather short."

The reader will see from this extract that the English "food for horses" is, in reality, not the same thing as the "chief o' Scotia's food;" and that a little agricultural knowledge would have prevented Dr Johnson from exhibiting, in the same sentence, an example of both his ignorance and his venom.

Variety affects appearance and quality; and how these are to be consulted in reference to the market in which the grain is to be sold, may be gathered from the following: —

"When wheat is quite opaque, indicating not the least translucency, it is in the best state for yielding the finest flour – such flour as confectioners use for pastry; and in this state it will be eagerly purchased by them at a large price. Wheat in this state contains the largest proportion of fecula or starch, and is therefore best suited to the starch-maker, as well as the confectioner. On the other hand, when wheat is translucent, hard, and flinty, it is better suited to the common baker than the confectioner and starch manufacturer, as affording what is called strong flour, that rises boldly with yeast into a spongy dough. Bakers will, therefore, give more for good wheat in this state than in the opaque; but for bread of finest quality the flour should be fine as well as strong, and therefore a mixture of the two conditions of wheat is best suited for making the best quality of bread. Bakers, when they purchase their own wheat, are in the habit of mixing wheat which respectively possesses those qualities; and millers who are in the habit of supplying bakers with flour, mix different kinds of wheat, and grind them together for their use. Some sorts of wheat naturally possess both these properties, and on that account are great favourites with bakers, though not so with confectioners; and, I presume, to this mixed property is to be ascribed the great and lasting popularity which Hunter's white wheat has so long enjoyed. We hear also of 'high mixed' Danzig wheat, which has been so mixed for the purpose, and is in high repute amongst bakers. Generally speaking, the purest coloured white wheat indicates most opacity, and, of course, yields the finest flour; and red wheat is most flinty, and therefore yields the strongest flour: a translucent red wheat will yield stronger flour than a translucent white wheat, and yet a red wheat never realises so high a price in the market as white – partly because it contains a larger proportion of refuse in the grinding, but chiefly because it yields less fine flour, that is, starch."

In regard to wheat, it has been supposed, that the qualities referred to in the above extract, as especially fitting certain varieties for the use of the confectioner, &c., were owing to the existence of a larger quantity of gluten in these kinds of grain. Chemical inquiry has, however, nearly dissipated that idea, and with it certain erroneous opinions, previously entertained, as to their superior nutritive value. Climate and physiological constitution induce differences in our vegetable productions, which chemical research may detect and explain, but may never be able to remove or entirely control.

The bran, or external covering of the grain of wheat, has recently also been the subject of scientific and economical investigation. It has been proved, by the researches of Johnston, confirmed by those of Miller and others, that the bran of wheat, though less readily digestible, contains more nutritive matter than the white interior of the grain. Brown, or household bread, therefore, which contains a portion of the bran, is to be preferred, both for economy and for nutritive quality, to that made of the finest flour.

Upon the economy of mixing potato with wheaten flour, and of home-made bread, Mr Stephens has the following: —

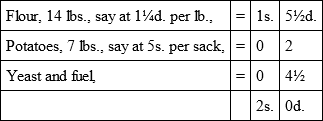

"It is assumed by some people, that a mixture of potatoes amongst wheaten flour renders bread lighter and more wholesome. That it will make bread whiter, I have no doubt; but I have as little doubt that it will render it more insipid, and it is demonstrable that it makes it dearer than wheaten flour. Thus, take a bushel of 'seconds' flour, weighing 56 lbs. at 5s. 6d. A batch of bread, to consist of 21 lbs., will absorb as much water, and require as much yeast and salt, as will yield 7 loaves, of 4 lbs. each, for 2s. 4d., or 4d. per loaf. 'If, instead of 7 lbs. of the flour, the same weight of raw potatoes be substituted, with the hope of saving by the comparatively low price of the latter article, the quantity of bread that will be yielded will be but a trifle more than would have been produced from 14 lbs. of flour only, without the addition of the 7 lbs. of potatoes; for the starch of this root is the only nutritive part, and we have proved that but one-seventh or one-eighth of it is contained in every pound, the remainder being water and innutritive matter. Only 20 lbs. of bread, therefore, instead of 28 lbs., will be obtained; and this, though white, will be comparatively flavourless, and liable to become dry and sour in a few days; whereas, without the latter addition, bread made in private families will keep well for 3 weeks, though, after a fortnight, it begins to deteriorate, especially in the autumn.' The calculation of comparative cost is thus shown: —

The yield, 20 lbs., or 5 loaves of 4 lbs. each, will be nearly 5d. each, which is dearer than the wheaten loaves at 4d. each, and the bread, besides, of inferior quality.

"'There are persons who assert – for we have heard them – that there is no economy in baking at home. An accurate and constant attention to the matter, with a close calculation of every week's results for several years – a calculation induced by the sheer love of investigation and experiment – enables us to assure our readers, that a gain is invariably made of from 1½d. to 2d. on the 4 lb. loaf. If all be intrusted to servants, we do not pretend to deny that the waste may neutralise the profit; but, with care and investigation, we pledge our veracity that the saving will prove to be considerable.' These are the observations of a lady well known to me."

In the natural history of barley the most remarkable fact is, the high northern latitudes in which it can be successfully cultivated. Not only does it ripen in the Orkney and Shetland and Faroe Islands, but on the shores of the White Sea; and near the North Cape, in north latitude 70°, it thrives and yields nourishment to the inhabitants. In Iceland, in latitude 63° to 66° north, it ceases to ripen, not because the temperature is too low, but because rains fall at an unseasonable time, and thus prevent the filling ear from arriving at maturity.

The oat is distinguished by its remarkable nutritive quality, compared with our other cultivated grains. This has been long known in practice in the northern parts of the island, where it has for ages formed the staple food of the mass of the population, though it was doubted and disputed in the south so much, as almost to render the Scotch ashamed of their national food. Chemistry has recently, however, set the matter at rest, and is gradually bringing oatmeal again into general favour. We believe that the robust health of many fine families of children now fed upon it, in preference to wheaten flour, is a debt they owe, and we trust will not hereafter forget, to chemical science.

On oatmeal Mr Stephens gives us the following information: —

"The portion of the oat crop consumed by man is manufactured into meal. It is never called flour, as the millstones are not set so close in grinding it as when wheat is ground, nor are the stones for grinding oats made of the same material, but most frequently only of sandstone – the old red sandstone or greywacke. Oats, unlike wheat, are always kiln-dried before being ground; and they undergo this process for the purpose of causing the thick husk, in which the substance of the grain is enveloped, to be the more easily ground off, which it is by the stones being set wide asunder; and the husk is blown away, on being winnowed by the fanner, and the grain retained, which is then called groats. The groats are ground by the stones closer set, and yield the meal. The meal is then passed through sieves, to separate the thin husk from the meal. The meal is made in two states: one fine, which is the state best adapted for making into bread, in the form called oat-cake or bannocks; and the other is coarser or rounder ground, and is in the best state for making the common food of the country people – porridge, Scottice, parritch. A difference of custom prevails in respect to the use of these two different states of oatmeal, in different parts of the country, the fine meal being best liked for all purposes in the northern, and the round or coarse meal in the southern counties; but as oat-cake is chiefly eaten in the north, the meal is there made to suit the purpose of bread rather than of porridge; whereas, in the south, bread is made from another grain, and oatmeal is there used only as porridge. There is no doubt that the round meal makes the best porridge, when properly made – that is, seasoned with salt, and boiled as long as to allow the particles to swell and burst, when the porridge becomes a pultaceous mass. So made, with rich milk or cream, few more wholesome dishes can be partaken by any man, or upon which a harder day's work can be wrought. Children of all ranks in Scotland are brought up on this diet, verifying the poet's assertion —