полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849

How would the Scriptores Rei Rusticæ have gained in usefulness in their own time, how immensely in interest in ours, had they been accompanied by such illustrations as these! The clearness of Columella would have been made more transparent, the obscurity of Palladius lessened; and Cato and Varro would have preserved to us the actual living forms, and costumes, and instruments of the ancient Etruscan times, more clearly than the painted tombs are now revealing to the antiquarian the fashions of their feasts, and games, and funereal rites. We have before us the singularly, richly, and extravagantly, yet graphically and most instructively illustrated book of Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica (Basil, 1621.) The woodcuts of the Book of the Farm have induced us to turn it up, and it is with ever new admiration that we turn over its old leaves. It has to us the interest of a child's picture-book; and though, as a chef-d'œuvre of illustrative art, the three hundred woodcuts of Stephens do not approach the book of Agricola, yet what a treasure would the work of Ausonius Popma on the rural implements of the ancients – their instrumenta in its widest sense – have been to us, could it have been illustrated when he wrote (1690) in the style of Agricola, and with the minuteness and fulness of Stephens!

The same desire to render minutely intelligible the whole subject treated of, which these woodcuts show, is manifested in the more solid letterpress of the book. It was said of Columella, by Matthew Gessner, that he discoursed "non ut argumentum simplex quod discere amat, dicendo obscuret, sed ut clarissimâ luce perfundat omnia." Such, the reader feels, must have been the aim of the author of this book. In his descriptions, nothing appears to be omitted; nothing is too minute to be passed over. His book exposes not merely the every-day life, but the very inmost life – the habits, and usages, and instruments of the most humble as well as the most important of the operations of the domestic, equally with the field economy of rural life. We do not know if its effects upon our town population will ever be such as Beza ascribes to that of Columella —

Tu vero, Juni, silvestria rura canendo,Post te ipsas urbes in tua rura trahis;but certainly, with a few more woodcuts, it would, in minute and graphic illustration, by prints and letterpress be a most worthy companion to the work of Agricola.

The plan of the book is to give a history of the agricultural year, after the manner of the Roman Palladius and our own old Tucker; and the present volume embraces the operations of the skilful farmer in every kind of husbandry during the winter and spring. But, before we come to the heart of the book, hear what Mr Stephens says about the agricultural learning of our landed gentry: —

"Even though he devote himself to the profession of arms or the law, and thereby confer distinction on himself, if he prefer either to the neglect of agriculture he is rendering himself unfit to undertake the duties of a landlord. To become a soldier or a lawyer, he willingly undergoes initiatory drillings and examinations; but to acquire the duties of a landlord before he becomes one, he considers it quite unnecessary to undergo initiatory tuition. These, he conceives, can be learned at any time, and seems to forget that the conducting of a landed estate is a profession, as difficult of thorough attainment as ordinary soldiership or legal lore. The army is an excellent school for confirming, in the young, principles of honour and habits of discipline; and the bar for giving a clear insight into the principles upon which the rights of property are based, and of the relation betwixt landlord and tenant; but a knowledge of practical agriculture is a weightier matter than either for a landlord, and should not be neglected.

"One evil arising from studying those exciting professions before agriculture is, that, however short may have been the time in acquiring them, it is sufficiently long to create a distaste to learn agriculture afterwards practically – for such a task can only be undertaken, after the turn of life, by enthusiastic minds. But as farming is necessarily the profession of the landowner, it should be learned, theoretically and practically, before his education is finished. If he so incline, he can afterwards enter the army or go to the bar, and the exercise of those professions will not efface the knowledge of agriculture previously acquired. This is the proper course, in my opinion, for every young man destined to become a landowner to pursue, and who is desirous of finding employment as long as he has not to exercise the functions of a landlord. Were this course invariably pursued, the numerous engaging ties of a country life would tend in many to extinguish the kindling desire for any other profession. Such a result would be most advantageous for the country; for only consider the effects of the course pursued at present by landowners. It strikes every one as an incongruity for a country gentleman to be unacquainted with country affairs. Is it not strange that he should require inducements to learn his hereditary profession, – to become familiar with the only business which can enable him to enhance the value of his estate, and increase his income? Does it not infer infatuation to neglect becoming well acquainted with the condition of his tenants, by whose exertions his income is raised, and by which knowledge he might confer happiness on many families, and in ignorance of which he may entail lasting misery on many more? It is in this way too many country gentlemen neglect their moral obligations.

"It is a manifest inconvenience to country gentlemen, when taking a prominent part in county matters without a competent knowledge of agriculture, to be obliged to apologise for not having sufficiently attended to agricultural affairs. Such an avowal is certainly candid, but is anything but creditable to those who have to make it. When elected members of the legislature, it is deplorable to find so many of them so little acquainted with the questions which bear directly or indirectly on agriculture. On these accounts, the tenantry are left to fight their own battles on public questions. Were landowners practically acquainted with agriculture, such painful avowals would be unnecessary, and a familiar acquaintance with agriculture would enable the man of cultivated mind at once to perceive its practical bearing on most public questions."

And what he says respectively of the ignorant and skilful factor or agent is quite as deserving of attention. Not merely whole estates, but in some parts of the island, whole counties lag in arrear through the defective education and knowledge of the agents as a class: —

"A still greater evil, because less personal, arises on consigning the management of valuable estates to the care of men as little acquainted as the landowners themselves with practical agriculture. A factor or agent, in that condition, always affects much zeal for the interest of his employer. Fired by it, and possessing no knowledge to form a sound judgment, he soon discovers something he considers wrong among the poorer tenants. Some rent perhaps is in arrear – the strict terms of the lease have been deviated from – the condition of the tenant seems declining. These are favourable symptoms for a successful contention with him. Instead of interpreting the terms of the lease in a generous spirit, the factor hints that the rent would be better secured through another tenant. Explanation of circumstances affecting the actual condition of the farm, over which he has, perhaps, no control, – the inapplicability, perhaps, of peculiar covenants in the lease to the particular circumstances of the farm – the lease having perhaps been drawn up by a person ignorant of agriculture, – are excuses unavailingly offered to a factor confessedly unacquainted with country affairs, and the result ensues in disputes betwixt him and the tenant. To explanations, the landlord is unwilling to listen, in order to preserve intact the authority of the factor; or, what is still worse, is unable to interfere, because of his own inability to judge of the actual state of the case betwixt himself and the tenant, and, of course, the disputes are left to be settled by the originator of them. Thus commence actions at law, – criminations and recriminations, – much alienation of feeling; and at length a proposal for the settlement of matters, at first perhaps unimportant, by the arbitration of practical men. The tenant is glad to submit to an arbitration to save his money; and in all such disputes, being the weaker party, he suffers most in purse and character. The landlord, who ought to have been the protector, is thus converted into the unconscious oppressor of his tenant.

"A factor acquainted with practical agriculture would conduct himself very differently in the same circumstances. He would endeavour to prevent legitimate differences of opinion on points of management from terminating in disputes, by skilful investigation and well-timed compromise. He would study to uphold the honour of both landlord and tenant. He would at once see whether the terms of the lease were strictly applicable to the circumstances of the farm, and, judging accordingly, would check improper deviations from proper covenants, whilst he would make allowances for inappropriate ones. He would soon discover whether the condition of the tenant was caused more by his own mismanagement than by the nature of the farm he occupies, and he would conform his conduct towards him accordingly – encouraging industry and skill, admonishing indolence, and amending the objectionable circumstances of the farm. Such a factor is always highly respected, and his opinion and judgment are entirely confided in by the tenantry. Mutual kindliness of intercourse, therefore, always subsists betwixt such factors and the tenants. No landlord, whether acquainted or unacquainted with farming, especially in the latter case, should confide the management of his estate to any person less qualified."

These extracts are long, but we feel we are rendering the public a service by placing them where they are likely to be widely read.

We have mentioned above that the Book of the Farm is full of that kind of clear home knowledge of rural life which the emigrant in foreign climes at all resembling our own will delight to read and profit by; but it will not supply the place of previous agricultural training. There is much truth and sound practical advice in the following observations: —

"Let every intending settler, therefore, learn agriculture thoroughly before he emigrates; and, if it suits his taste, time, and arrangements, let him study in the colony the necessarily imperfect system pursued by the settlers, before he embarks in it himself; and the fuller knowledge acquired here will enable him, not only to understand the colonial scheme in a short time, but to select the part of the country best suited to his purpose. But, in truth, he has much higher motives for learning agriculture here; for a thorough acquaintance will enable him to make the best use of inadequate means – to know to apply cheap animal instead of dear manual labour, – to suit the crop to the soil, and the labour to the weather; – to construct appropriate dwellings for himself and family, live stock, and provisions; to superintend every kind of work, and to show a familiar acquaintance with them all. These are qualifications which every emigrant may acquire here, but not in the colonies without a large sacrifice of time – and time to a settler thus spent is equal to a sacrifice of capital, whilst eminent qualifications are equivalent to capital itself. This statement may be stigmatised by agricultural settlers who may have succeeded in amassing fortunes without more knowledge of agriculture than what was picked up by degrees on the spot; but such persons are incompetent judges of a statement like this, never having become properly acquainted with agriculture; and however successful their exertions may have proved, they might have realised larger incomes in the time, or as large in a shorter time, had they brought an intimate acquaintance of the most perfect system of husbandry known, to bear upon the favourable circumstances they occupied."

The early winter is spent in ploughing, which we pass over, and mid-winter chiefly in feeding stock, in threshing out the corn, and in attending to composts and dunghills. Preparing and sowing the seed is the most important business of the spring months, to which succeeds the tending of the lambs and ewes, and the preparation of the land for the fallow or root crops. These several operations are treated of in their most minute details, and the latest methods adopted in reference to every point are fully explained.

In the husbandry of the most advanced portions of our island, the turnip occupies a most important place in the estimation of the skilful farmer, whether his dependence for the means of paying his rent be placed upon the profits of his corn crops or of his cattle.

Of the turnip we have now many varieties – though it is only seventy or eighty years since it was first introduced into field culture – at least in those districts of the island in which its importance is most fully recognised. The history of its introduction into Scotland is thus given by Mr Stephens —

"The history of the turnip, like that of other cultivated plants, is obscure. According to the name given to the swede in this country, it is a native of Sweden; the Italian name Navoni di Laponia intimates an origin in Lapland, and the French names Chou de Lapone, Chou de Suède, indicate an uncertain origin. Sir John Sinclair says, 'I am informed that the swedes were first introduced into Scotland anno 1781-2, on the recommendation of Mr Knox, a native of East Lothian, who had settled at Gottenburg, whence he sent some of the seeds to Dr Hamilton.' There is no doubt the plant was first introduced into Scotland from Sweden, but I believe its introduction was prior to the date mentioned by Sir John Sinclair. The late Mr Airth, Mains of Dunn, Forfarshire, informed me that his father was the first farmer who cultivated swedes in Scotland, from seeds sent him by his eldest son, settled in Gottenburg, when my informant, the youngest son of a large family, was a boy of about ten years of age. Whatever may be the date of its introduction, Mr Airth cultivated them in 1777; and the date is corroborated by the silence preserved by Mr Wight regarding its culture by Mr Airth's father when he undertook the survey of the state of husbandry in Scotland, in 1773, at the request of the Commissioners of the Annexed Estates, and he would not have failed to report so remarkable a circumstance as the culture of so useful a plant, so that it was unknown prior to 1773. Mr Airth sowed the first portion of seed he received in beds in the garden, and transplanted the plants in rows in the field, and succeeded in raising good crops for some years, before sowing the seed directly in the fields."

The weight of a good turnip crop – not of an extraordinary crop, which some persons can succeed in raising, and the accounts of which others only refuse to credit – is a point of much importance; and it is so, not merely to the farmer who possesses it, but to the rural community at large. The conviction that a certain given weight is a fair average crop in well-farmed land, where it does not exceed his own, will be satisfactory to the industrious farmer; while it will serve as a stimulus to those whose soil, or whose skill, have hitherto been unable to raise so large a weight. According to our author —

"A good crop of swede turnips weighs from 30 to 35 tons per imperial acre.

"A good crop of yellow turnips weighs from 30 to 32 tons per imperial acre.

"A good crop of white globe turnips weighs from 30 to 40 tons per imperial acre."

Of all kinds of turnips, therefore, from 30 to 40 tons per imperial acre are a good crop.

The readers of agricultural journals must have observed that, of late years, the results of numerous series of experiments have been published. Among those that have been made upon turnips, he will have noticed also that the crop, in about nine cases out of ten, is under twenty tons; that these crops vary, for the most part, between nine and sixteen tons; and that some farmers are not ashamed to publish to the world, that they are content with crops of from seven to ten tons of turnips an acre. Where is our skill in the management of turnip soils, if, in the average of years, such culture and crops satisfy any considerable number of our more intelligent tenantry? We know that soil, and season, and locality, and numerous accidents, affect the produce of this crop; but the margin between the actual and the possible is far too wide to be accounted for in this way. More skill, more energy, more expenditure in draining, liming, and manuring – a wider diffusion of our practical and scientific agricultural literature – these are the means by which the wide margin is to be narrowed; by which what is in the land is to be brought out of the land, and thereby the farmer made more comfortable, and the landlord more rich.

The subject of sheep and cattle feeding is very important, and very interesting, and our book is rich in materials which would provoke us to discuss it at some length, did our limits admit of it. We must be content, however, with a few desultory extracts.

The following, in regard to sheep feeding upon turnips, is curious, and, in our opinion, requires repetition: —

"A curious and unexpected result was brought to light by Mr Pawlett, and is thus related in his own words, – 'Being aware that it was the custom of some sheep-breeders to wash the food, – such as turnips, carrots, and other roots, – for their sheep, I was induced also to try the system; and as I usually act cautiously in adopting any new scheme, generally bringing it down to the true standard of experience, I selected for the trial two lots of lambs. One lot was fed, in the usual manner, on carrots and swedes unwashed; the other lot was fed exactly on the same kinds of food, but the carrots and swedes were washed very clean every day: they were weighed before trial, on the 2d December, and again on the 30th December, 1835. The lambs fed with the unwashed food gained each 7½ lb., and those on the washed gained 4¾ lb. each; which shows that those lambs which were fed in the usual way, without having their food washed, gained the most weight in a month by 2¾ lb. each lamb. There appears to me no advantage in this method of management – indeed animals are fond of licking the earth, particularly if fresh turned up; and a little of it taken into the stomach with the food must be conducive to their health, or nature would not lead them to take it.'"

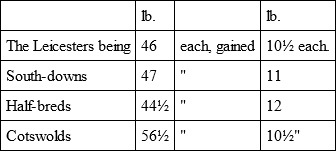

Another experiment on the fattening properties of different breeds of sheep, under similar treatment, quoted from the Journal of the Royal Agricultural Society of England, is also deserving the attention of our readers: —

"Experiments were made in 1844-5 on the Earl of Radnor's farm at Coleshill, on the comparative fattening properties of different breeds of sheep under the same treatment. The sheep consisted of Leicesters, South-downs, half-breds, – a cross between the Cotswold and South-down – and Cotswolds. The sheep, being then lambs, were divided into lots of three each of each breed, and were grazed four months, from 29th August 1844 to 4th January 1845, when they were put on hay and swedes for three months, from 4th January to the 31st of March following. While on grass, the different breeds gained in weight as follows: —

It is one of the most delicate qualifications connected with the stock-feeder's art to be able to select that stock, and that variety of it, which, under all the circumstances in which he is placed, will give him the largest return in money – hence every experiment like the above, if well conducted, is deserving of his close attention. At the same time, in rural experiments, more almost than in any other, the number of elements which interfere with the result, and may modify it, is so great, that too much confidence ought not to be placed upon single trials. Repeated results of one kind must be obtained, before a farmer can be justified in spending much money on the faith of them.

In turning to the winter feeding of cattle upon turnips and other food – a subject important enough to justify Mr Stephens in devoting forty of his closely printed pages to it – we are reminded of a character of this book which we like very much, which squares admirably with our own idea of neatness, order, and method, and which we heartily commend to the attention of our farming friends: this is the full and minute description he gives of the duties of every class of servants upon the farm, of the necessity of having these duties regularly and methodically performed, and of the way in which the master may bring this about.

The cattle-man is an important person in the winter feeding of cattle; he therefore commences this section with an account of the duties and conduct of this man. Even his dress he describes; and the following paragraph shows his reason for drawing the young farmer's attention to it: —

"The dress of a cattle-man is worth attending to, as regards its appropriateness for his business. Having so much straw to carry on his back, a bonnet or round-crowned hat is the most convenient head-dress for him; but what is of more importance when he has charge of a bull, is to have his clothes of a sober hue, free of gaudy or strongly-contrasted colours, especially red, as that colour is peculiarly offensive to bulls. It is with red cloth and flags that the bulls in Spain are irritated to action at their celebrated bull-fights. Instances are in my remembrance of bulls turning upon their keepers, not because they were habited in red, but from some strongly contrasted bright colours. It was stated that the keeper of the celebrated bull Sirius, belonging to the late Mr Robertson of Ladykirk, wore a red nightcap on the day the bull attacked and killed him. On walking with a lady across a field, my own bull – the one represented in the plate of the Short-horn Bull, than which a more gentle and generous creature of his kind never existed – made towards us in an excited state; and for his excitement I could ascribe no other cause than the red shawl worn by the lady, for as soon as we left the field he resumed his wonted quietness. I observed him excited, on another occasion, in his hammel, when the cattle-man – an aged man, who had taken charge of him for years – attended him one Sunday forenoon in a new red nightcap, instead of his usual black hat. Be the cause of the disquietude in the animal what it may, it is prudential in a cattle-man to be habited in a sober suit of clothes."

Then, after insisting upon regularity of time in everything he does, following the man through a whole day's work, describing all his operations, and giving figures of all his tools, – his graip, his shovel, his different turnip choppers, his turnip-slicer, his wheel-barrow, his chaff-cutters, his linseed bruisers, and his corn-crushers, – he gives us the following illustration of the necessity of regularity and method, and of the way to secure them: —

"In thus minutely detailing the duties of the cattle-man, my object has been to show you rather how the turnips and fodder should be distributed relatively than absolutely; but whatever hour and minute the cattle-man finds, from experience, he can devote to each portion of his work, you should see that he performs the same operation at the same time every day. By paying strict attention to time, the cattle will be ready for and expect their wonted meals at the appointed times, and will not complain until they arrive. Complaints from his stock should be distressing to every farmer's ears, for he may be assured they will not complain until they feel hunger; and if allowed to hunger they will not only lose condition, but render themselves, by discontent, less capable of acquiring it when the food happens to be fully given. Wherever you hear lowings from cattle, you may safely conclude that matters are conducted there in an irregular manner. The cattle-man's rule is a simple one, and easily remembered, —Give food and fodder to cattle at fixed times, and dispense them in a fixed routine. I had a striking instance of the bad effects of irregular attention to cattle. An old staid labourer was appointed to take charge of cattle, and was quite able and willing to undertake the task. He got his own way at first, as I had observed many labouring men display great ingenuity in arranging their work. Lowings were soon heard from the stock in all quarters, both in and out of doors, which intimated the want of regularity in the cattle-man; whilst the poor creature himself was constantly in a state of bustle and uneasiness. To put an end to this disorderly state of things, I apportioned his entire day's work by his own watch; and on implicitly following the plan, he not only soon satisfied the wants of every animal committed to his charge, but had abundant leisure to lend a hand to anything that required his temporary assistance. His old heart overflowed with gratitude when he found the way of making all his creatures happy; and his kindness to them was so undeviating, they would have done whatever he liked."