полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849

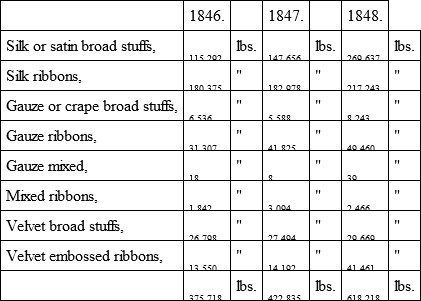

The labour market in this country, so far from improving, is, we have every reason to believe, in a pitiable state. Let us take the one instance of silk manufactures. Of these we exported, during eleven months of last year, an amount to the value of £912,842; this year we have only sent out £520,427, or nearly £400,000 less. But this decline does not by any means express the amount of the curtailment of labour in this important branch of industry. The home market has been inundated with foreign silks, introduced under the tariffs of 1846, and that to a degree which is wholly without precedent. Let us see the comparative amount of importations.

Is there any commentary required on these figures? We should hope that no one can be dull enough to misapprehend their import. In one year our exportation of silk goods has fallen to little more than a half: in two years our importations from the Continent have nearly doubled. Where ninety British labourers worked for the exporting trade, only fifty are now employed; and if we suppose that the consumpt of silk manufactures in this country is the same in 1848 as in 1846, the further amount of labour which has been sacrificed, by the increased importations, must be something positively enormous. It is in this way that free trade beggars the people and fills the workhouses; whilst, at the same time, it brings down the national revenue to such an ebb, that it is utterly insufficient to balance the necessary expenditure. It would be well if politicians would constantly keep in view this one great truth – That of all the burdens which can be laid upon a people, the heaviest is the want of employment. No general cheapness, no class accumulations of wealth, can make up for this terrible want; and the statesman who deliberately refuses to recognise this principle, and who, from any motive, deprives the working man of his privilege, is an enemy to the interests of his country.

We cannot, and we do not, expect that men who have committed themselves so deeply as Mr Cobden has done to the principles of free trade in all its branches, should, under any development of circumstances, be brought to acknowledge their error. No evidence however overwhelming, no ruin however widely spread, could shake their faith, or at any rate diminish the obstinacy of their professions. They would rather sacrifice, as indeed they seem bent on doing, the best interests of the British empire, than acknowledge the extent of their error. Their motto avowedly is, vestigia nulla retrorsum. No sooner is one interest pulled down than they make a rapid and determined assault upon another, utterly reckless of the misery which they have occasioned, and hopelessly deaf even to the warnings of experience. They are true destructives; because they feel that they dare not pause in their career of violence, lest men should have leisure, to contemplate the ruin already effected, and should ask themselves what tangible benefit has been obtained at so terrible a cost. Mr Cobden knows better than to resume consideration of free-trade principles, now that we have seen them in actual operation. He is advancing on with his myrmidons towards the Moscow of free trade; but, unless we are greatly mistaken, he may have occasion, some day or other, to revisit his ancient battlefields, but not in the capacity of a conqueror. There are, however, others, less deeply pledged, who begin to perceive that in attempting to carry out free trade without reciprocity, and in the face of hostile tariffs, we are ruining the trade of Britain for the sole advantage of the foreigner. Mr Muntz, the member for Birmingham, is not at one with ministers as to the cheerful prospect of the revival among the manufacturers.

"When I came here," said he characteristically, "I heard a great deal about the improvement of trade in the country. But I went home on Saturday, and there was not a man I met who had experienced any of this improvement in trade. On the contrary, every one said that trade was flat and unprofitable, and that there was no prospect of improvement because they were so much competed with by foreign manufacturers. This very morning I met with one of my travellers, who had just returned from the north of Germany; and I asked him what was the state of trade. 'Oh,' said he, 'there is plenty of trade in Germany, but not trade with England. They manufacture goods so cheaply themselves, that, at the prices you sell, low as they are, you cannot compete with the Germans.' I will tell the House another curious thing. About three or four years ago, the glassmakers of Birmingham were very anxious for free trade, and, though I warned them that I did not think they could compete with foreigners, yet they were quite certain they could. Well, I introduced them to the minister of the day – the right honourable baronet the member of Tamworth – when, to my horror and astonishment, they asked, not for free trade, but for three years of protection. Why, I said to them, I thought you were for free trade? 'Yes,' they replied, 'so we are; but we want the three years of protection to prepare us for free trade.' Now, on Saturday last, I received a letter from one of the leading manufacturers, stating that the import duties on flint-glass would expire very soon, and with those duties the trade in this country, he feared, was also in great danger of expiring, owing to the produce of manufactures being admitted duty-free into this country, while they had protective duties in their own, thus keeping up the price at home by sending over the surplus stock here. The letter concluded by requesting that the protective duties, which were about to expire, might be renewed. The improvement in trade, which was so much talked of, is not an improvement in quality, but an improvement in quantity: there are half a dozen other trades which have vanished from Birmingham, because of the over-competition of the Continent. And, strangely enough, the manufactures that have been the most injured are those which last week were held up by the public press as in a most flourishing condition!"

This statement furnishes ample ground for reflection. The truth is, that the whole scheme of free trade was erected and framed, not for the purpose of benefiting the manufacturers at the expense of the landed interest, but rather to get a monopoly of export for one or two of the leading manufactures of the empire. Those who were engaged in the cotton and woollen trade, along with some of the iron-masters, were at the head of the movement. No influx of foreign manufactured produce could by possibility swamp them in the home market, for they are not exposed to that competition with which the smaller trades must struggle. The Germans will take shirtings, but they will not now take cutlery from us. The articles which they produce are certainly not so good as ours, but they are cheaper, and protected, and it is even worth their while to compete with us in the home markets of Britain. The same may be said of the trade in brass, gloves, shoes, hats, earthenware, porcelain, and fifty others. They are not now exporting trades, and at home, under the new tariffs, we are completely undersold by the foreigners. As for the glass trade, no one who is acquainted with the present state of that manufacture on the Continent, can expect that it will ever again recover. This, in reality, is the cause of the present depression; and until this is thoroughly understood by the tradesmen who are suffering, there can be no improvement for the better. What advantage, we ask, can it be to a man who finds his profits disappearing, his trade reduced to stagnation, and his capability of giving employment absolutely annihilated, to know that, in consequence of some sudden impulse, twenty million additional yards of calico have been exported from Great Britain? The glass-blower, the brazier, and the cutler, have not the remotest interest in calico. They may think, indeed, that part of the profit so secured may be indirectly advantageous in the purchase of their wares, but they find themselves lamentably mistaken. The astute calico-master sells his wares to the foreigner abroad, and he purchases with equal disinterestedness from the manufacturing foreigner at home. This is the whole tendency of free trade, and it is amazing to us that the juggle should find any supporters amongst the class who are its actual victims. If they look soberly and deliberately into the matter, they cannot fail to see that the adoption by the state of the maxim, to sell in the dearest and buy in the cheapest market, more especially when that market is the home one, and when cheapness has been superinduced by the introduction of foreign labour, must end in the consummation of their ruin. Can we really believe in the assertion of ministers, that manufactures are improving, when we find, on all hands, such pregnant assurances to the contrary? For example, there was a meeting held in St James's, so late as the 11th of January, "to consider the unprecedented number of unemployed mechanics and workmen now in the metropolis, and to devise the best means for diminishing their privations and sufferings, by providing them with employment." Mr Lushington, M.P. for Westminster, a thorough-paced liberal, moved the first resolution, the tendency of which was towards the institution of soup kitchens, upon this preamble, "that the number of operatives, mechanics, and labourers now thrown out of employment is unusually great, and the consequent destitution and distress which exist on all sides are painfully excessive, and deeply alarming." And yet, Mr Lushington, like many of his class and stamp, can penetrate no deeper into the causes of distress, than is exhibited in the following paragraph of his speech: – "The great majority of those whose cases they were now met to consider, were the victims of misfortune, and not of crime, and, on that account, they had a legitimate claim upon their sympathy and commiseration. But private sympathy was impotent to grapple with the gigantic evil with which they had to contend; isolated efforts and voluntary alms-giving were but a mere drop in the ocean, compared with the remedy that the case demanded. They must go further and deeper for their remedy; and the only efficacious one that could effectually be brought to bear upon the miseries of the people, was the reduction of the national expenditure – the cutting down of the army, navy, and ordnance estimates, and the removal of those taxes that pressed so heavily upon the poorer portions of the community." This is about as fine a specimen of unadulterated senatorial drivel as we ever had the good fortune to meet with; and it may serve as an apt illustration of the absurd style of argument so commonly employed by the members of the free-trade party. Suppose that the army were disbanded to-morrow, and all the sailors in the navy paid off, how would that give employment to the unfortunate poor? Nay, would it not materially contribute to increase the tide of pauperism, since no economist has as yet condescended to explain what sort of employment is to be given to the disbanded? As to the taxes spoken of by Mr Lushington, what are they? We really cannot comprehend the meaning of this illustrious representative of an enlightened constituency. Supposing there was not a single tax levied in Britain to-morrow, how would that arrangement better the condition of the people, who are simply starving because they can get no manner of work whatever? It is this silly but mischievous babbling, these false and illogical conclusions enunciated by men who either do not understand what they are saying, or who, understanding it, are unfit for the station which they occupy, which tend more than anything else to spread disaffection among the lower orders, to impress them with the idea that they are unjustly dealt with, and to stimulate them in their periodical outcry for organic changes. The remedy lies in restoring to the labouring man those privileges of which he has been insidiously robbed by the operation of the free-trade measures. It lies in returning to the system which secured a full revenue to the nation, whilst, at the same time, it prevented the minor trades from being swamped by foreign competition. It lies in refusing to allow one class of the community to extinguish others, and to throw the burden of the pauperism which it creates upon the landed interest, already contending with enormous difficulties. Until this be done, it is in vain to expect any real improvement in the condition of the working-classes. Each successive branch of industry that is pulled down, under the operation of the new system, adds largely to the mass of accumulating misery; and the longer the experiment is continued, the greater will be the permanent injury to the country.

Not the least evil resulting from the free-trade agitation is the selfishness and division of classes which it has studiously endeavoured to promote. So long as the agriculturists alone were menaced, the whole body of the manufacturers were against them. The tariffs of 1846 struck at the small traders and artisans, and the merchants looked on with indifference. Now the question relates to the Navigation Laws, and the shipmasters of Britain complain that they cannot rouse the nation to a sense of the meditated wrong. Every one has been ready to advocate free trade in every branch save that with which he was personally connected; and it is this shortsighted policy which has given such power to the assailing party. Deeply do we deplore the folly as well as the wickedness of such divisions. No nation can ever hope to prosper through the prosperity of one class alone. It is not the wealth of individuals which gives stability to a state, but the fair distribution of profitable labour throughout the whole of the community. In contending for the support of the Navigation Laws, we are not advocating the cause of the shipmasters, but that of the nation; and yet we feel that if the principle of free trade be once fully admitted, no exception can be made, even in this vital point. If we intend to retain our colonies, we must do justice to them one way or another. We cannot deprive them of the advantages which they formerly enjoyed from their connexion with the parent country, and yet subject them to a burden of this kind, even although we hold that burden necessary for the effectual maintenance of our marine. We await the decision of this matter in parliament with very great anxiety indeed, because we look upon the adoption or the rejection of Mr Labouchere's bill as the index to our future policy. If it receives the royal assent, we must perforce prepare for organic changes far greater than this country has ever yet experienced. The colonies may still, indeed, be considered as portions of the British empire, but hardly worth the cost of retention. Free trade will have done its work. The excise duties cannot be suffered to continue, for they too, according to the modern idea, are oppressive and unjust; and the period, thus foreshadowed by Mr Cobden at the late Manchester banquet, will rapidly arrive: "It is not merely protective duties that are getting out of favour in this country; but, however strong or weak it may be at present, still there is firmly and rapidly growing an opinion decidedly opposed, not merely to duties for protection, but to duties for revenue at all. I venture to say you will not live to see another statesman in England propose any customs-duty on a raw material or article of first necessity like corn. I question whether any statesman who has any regard for his future fame will ever propose another excise or customs-duty at all." The whole revenue will then fall to be collected directly: and how long the national creditor will be able to maintain his claim against direct taxation is a problem which we decline to solve. The land of Great Britain, like that of Ireland, will be worthless to its owner, and left to satisfy the claims of pauperism; and America, wiser than the old country, will become to the middle classes the harbour of refuge and of peace.

We do not believe that these things will happen, because we have faith in the sound sterling sense of Englishmen, and in the destinies of this noble country. We are satisfied that the time is rapidly approaching when a thorough reconstruction of our whole commercial and financial policy will be imperatively demanded from the government – a task which the present occupants of office are notoriously incapable of undertaking, but which must be carried through by some efficient cabinet. Such a measure cannot be introduced piecemeal after the destructive fashion, but must be based upon clear and comprehensive principles, doing justice to all classes of the community, and showing undue favour to none.

Our observations have already extended to such a length, that we have little room to speak of that everlasting topic, Ireland. "Ireland," says Lord John Russell, "is undergoing a great transition." This is indeed news, and we shall be glad to learn the particulars so soon as convenient. Perhaps the transition may be explained before the committee, to which, as usual, Whig helplessness and imbecility has referred the whole question of Irish distress. The confidence of the Whigs in the patience of the people of this country must be boundless, else they would hardly have ventured again to resort to so stale an expedient. It is easy to devolve the whole duties of government upon committees, but we are very much mistaken if such trifling will be longer endured. As to the distress in Ireland, it is fully admitted. Whenever the bulk of a nation is so demoralised as to prefer living on alms to honest labour, distress is the inevitable consequence; and the only way to cure the habit is carefully to withhold the alms. Ministers think otherwise, and they have carried a present grant of fifty thousand pounds from the imperial exchequer, which may serve for a week or so, when doubtless another application will be tabled. This is neither more nor less than downright robbery of the British people under the name of charity. Ireland must in future be left to depend entirely upon her own resources; situated as we are, it would be madness to support her further; and we hope that every constituency throughout the United Kingdom will keep a watchful eye on the conduct pursued by their representatives in the event of any attempt at further spoliation. From all the evidence before us, it appears that our former liberality has been thrown away. Not only was no gratitude shown for the enormous advances of last year, but the money was recklessly squandered and misapplied, no doubt in the full and confident expectation of continued remittances. And here we beg to suggest to honourable members from the other side of the Channel, whether it might not be well to consider what effect free trade has had in ameliorating the condition of Ireland. If on inquiry at Liverpool they should chance to find that pork is now imported direct from America, not only salted, but fresh and preserved in ice, and that in such quantities and at so low a rate as seriously to affect the sale of the Irish produce, perhaps patriotism may operate in their minds that conviction which reasoning would not effect. If also they should chance to learn that butter and dairy produce can no longer command a remunerative price, owing to the increased imports both from America and the Continent, they will have made one further step towards the science of political economy, and may form some useful calculations as to the prospect of future rentals. Should they, however, still be of opinion that the interests of the Irish people are inseparably bound up with the continuance of free trade – that neither prices nor useful labour are matters of any consequence – they must also bear in mind that they can no longer be allowed to intromit with the public purse of Britain. The Whigs may indeed, and probably will, make one other vigorous effort to secure their votes; but no party in this nation is now disposed to sanction such iniquitous proceedings, and all of us will so far respond to the call for economy, as sternly to refuse alms to an indolent and ungrateful object.

In conclusion, we shall merely remark that we look forward with much interest to the financial exposition of the year, in the hope that it may be more intelligible and satisfactory than the last. We shall then understand the nature and the amount of the reductions which have been announced under such extraordinary circumstances, and the state of the revenue will inform those who feel themselves oppressed by excise duties, of the chances of reduction in that quarter. Meanwhile we cannot refrain from expressing our gratitude to both Lord Stanley and Mr D'Israeli for their masterly expositions of the weak and vacillating policy pursued by the Whig government abroad, and of the false colour which was attempted to be thrown upon the state and prospect of industry at home. Deeply as we lamented the premature decease of Lord George Bentinck at the very time when the value of his public service, keen understanding, and high and exalted principle, was daily becoming more and more appreciated by the country, we are rejoiced to know that his example has not been in vain; that his noble and philanthropic spirit still lives in the councils of those who have the welfare of the British people at heart, and who are resolute not to yield to the pressure of a base democracy, actuated by the meanest of personal motives, unscrupulous as to the means which it employs, impervious to reason, and utterly reckless of consequences, provided it may attain its end. Against that democracy which has elsewhere not only shattered constitutions but prostrated society, a determined stand will be made; and our heartfelt prayer is, that the cause of truth may prevail.

1

Stephens' Book of the Farm, Second Edition, vol. I.

2

In a recent number of the North British Agriculturist, it is stated that an agricultural stoker, who thought himself qualified to discourse on the uses of science to agriculture, had astonished a late meeting of the Newcastle Farmers' Club by telling them that the only thing science had yet done for agriculture was to show them how to dissolve bones in sulphuric acid; and that chemistry might boast of having really effected something if it could teach him to raise long potatoes, as he used to do, or to grow potato instead of Tartary oats, as his next-door neighbour could do. No wonder the shrewd Tyne-siders were astonished.

3

Where ¶ (pilcrow,) or paragraph, is placed at the side of the verse.

4

Tibullus, iii. 4, 55.

5

Système des Contradictions Economiques; ou Philosophie de la Misère. Par J. P. Prudhon.

6

Vol. ii., p. 461.

7

Cellar for goods.

8

Asylum of the world.

9

District judicial courts.

10

Flush—i. e., level.

11

Steward and Butler.

12

Sport.

13

Turban-wearing.

14

Little Girl! Do you hear, sweet one?

15

Officer.

16

Look.

17

'Tis a lie, you scoundrel.

18

That is true.

19

"Mother Carey," – an obscure sea-divinity chiefly celebrated for her "chickens," as Juno ashore for her peacocks. Quere, – a personification of the providential Care of Nature for her weaker children, amongst whom the little stormy petrels are conspicuous; while, at the same time, touchingly associating the Pagan to the Christian sea mythology by their double name – the latter, a diminutive of Peter walking by faith upon the waters. In the nautical creed, "Davy Jones" represents the abstract power, and "Mother Carey" the practically developed experience, which together make up the life Oceanic.

20

Histoire de Don Pédre Ier, Roi de Castille. Par Prosper Mérimée, de l'Académie Française. Pp. 586. Paris, 1848.